A new report on venture capital brings interesting conclusions and updates. Here is the summary that you can also fidn on the Nesta web site:

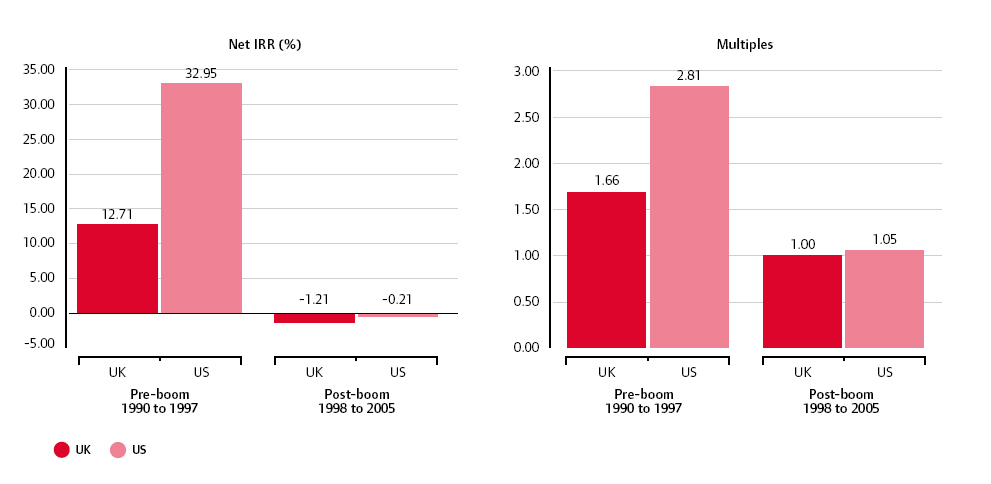

1. The returns performance of UK and US VC funds in recent years has been very similar. UK funds have historically underperformed US funds, but this gap has significantly narrowed. The gap in fund returns (net IRR) between the average US and UK fund has fallen from over 20 percentage points before the dotcom bubble (funds raised in 1990-1997) to one percentage point afterwards (funds raised in 1998-2005). However, this convergence has been driven by declining returns in the US after the burst of the dotcom bubble, rather than by increasing returns in the UK. Average returns for funds raised after the bubble in both the UK and the US have been relatively poor, but VC performance is likely to move upwards as VC funds start to cash out their investments in social networks (particularly in the US).

2. The wider environment in which UK funds and the companies they finance operate was a major contributor to the historical gap in VC returns. While there are some large differences in the observable characteristics of VC funds between both countries, they cannot account for the historical returns gap.

3. Average returns obscure the large variability in returns within countries. The dispersion in returns across funds was highest during the pre-bubble years, and has fallen significantly since then. But in both periods the gap in returns between good and bad performing funds within a country was much larger than the gap in the average returns across countries. Thirteen per cent of UK funds established since 1990, would have got into the top quartile of US funds by returns (this has increased to 22 per cent for funds established in the post bubble period), while 45 per cent of UK funds outperformed the median US fund. Selecting the right fund manager is thus more important than choosing a particular country.

4. The strongest quantifiable predictors of VC returns performance are

(a) whether the fund managers’ prior funds outperform the market benchmark;

(b) whether the fund invests in early rounds;

(c) whether the fund managers have prior experience; and

(d) whether the fund is optimally sized (neither too big nor too small).

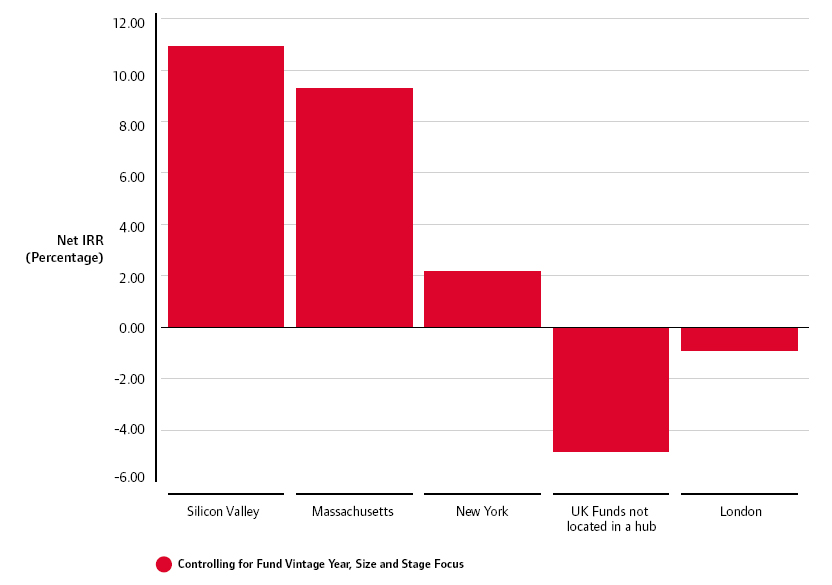

Moreover, historical performance has been higher for funds located in one of the four largest investor hubs (Silicon Valley, New York, Massachusetts and London) and for investments in information and communication technology.

5. UK government-backed funds have historically underperformed their private counterparts, but the gap between public and private returns has narrowed in recent periods. This suggests that in later years governments have become savvier when designing new VC schemes.

Most US funds have traditionally only invested locally, with less than a third of US funds raised between 1990 and 2005 having invested in one or more companies outside the US. In contrast, the majority of European funds have invested outside of their home market.

The situation has changed somewhat in recent times. A higher proportion of European funds raised in 2006-2009 have chosen to invest locally while US-based funds are becoming more global. As a result, the proportion of European VC capital being invested in the US has halved, falling to 10 per cent, and a slightly larger share of US VC capital is coming to Europe.

Overall, this analysis suggests that Europe does not offer an attractive proposition to US VC funds. Europe has a less developed VC market than the US, so attracting US funds (their money but also, crucially, their expertise) ought to benefit European economies. Instead, the opposite is happening. A much larger share of European VC funds invest in the US than the other way around. While Europe is likely to benefit from its funds investing in the US (for the returns it provides, the network it builds and the experience it generates), the small flow in the opposite direction is a cause for concern.

In conclusion

– The global venture capital industry is concentrated in very few hubs (and does not exist in a vacuum)

– The convergence in returns is not the result of changes in the characteristics of UK funds

– Small funds underperform medium sized funds, but larger is not always better

– More experienced fund managers achieved higher returns

– Past performance predicts future performance

– Funds in investor hubs had better returns

Investing in earlier rounds leads to better performance

– But much of the variability in returns is not explained by these factors

Finally some advice on Policy:

Remember venture capital activity does not exist in a vacuum.

Resist the temptation to overengineer public support schemes

Avoid initiatives that are too small.

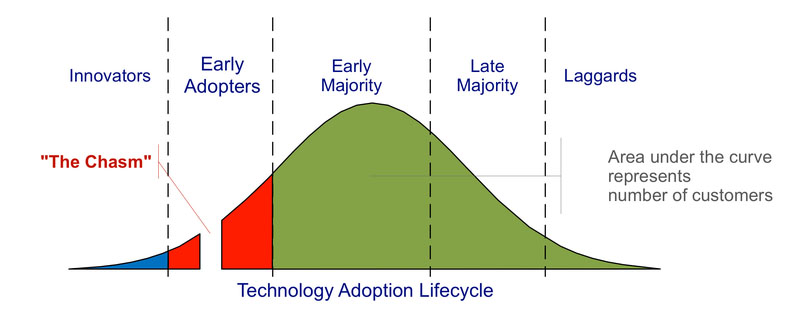

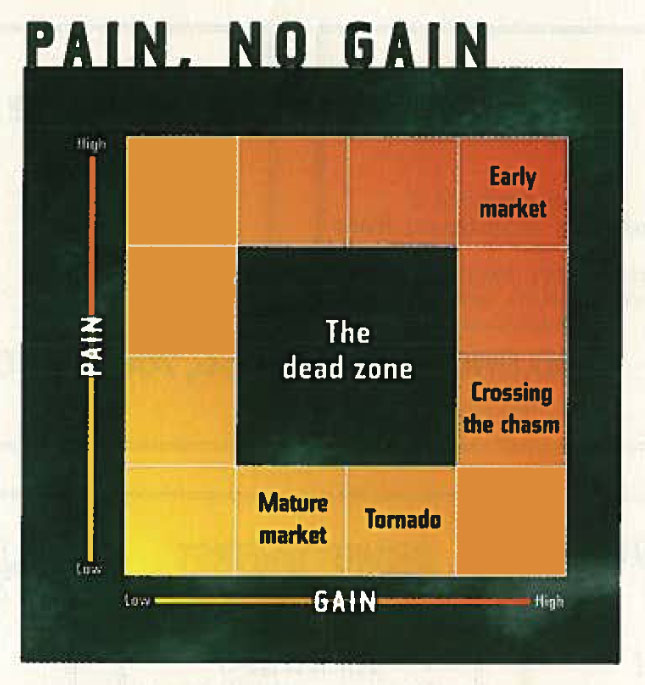

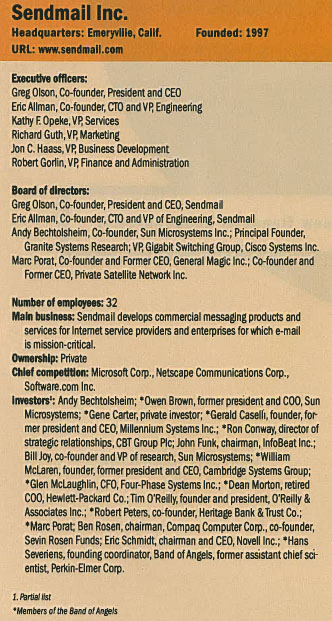

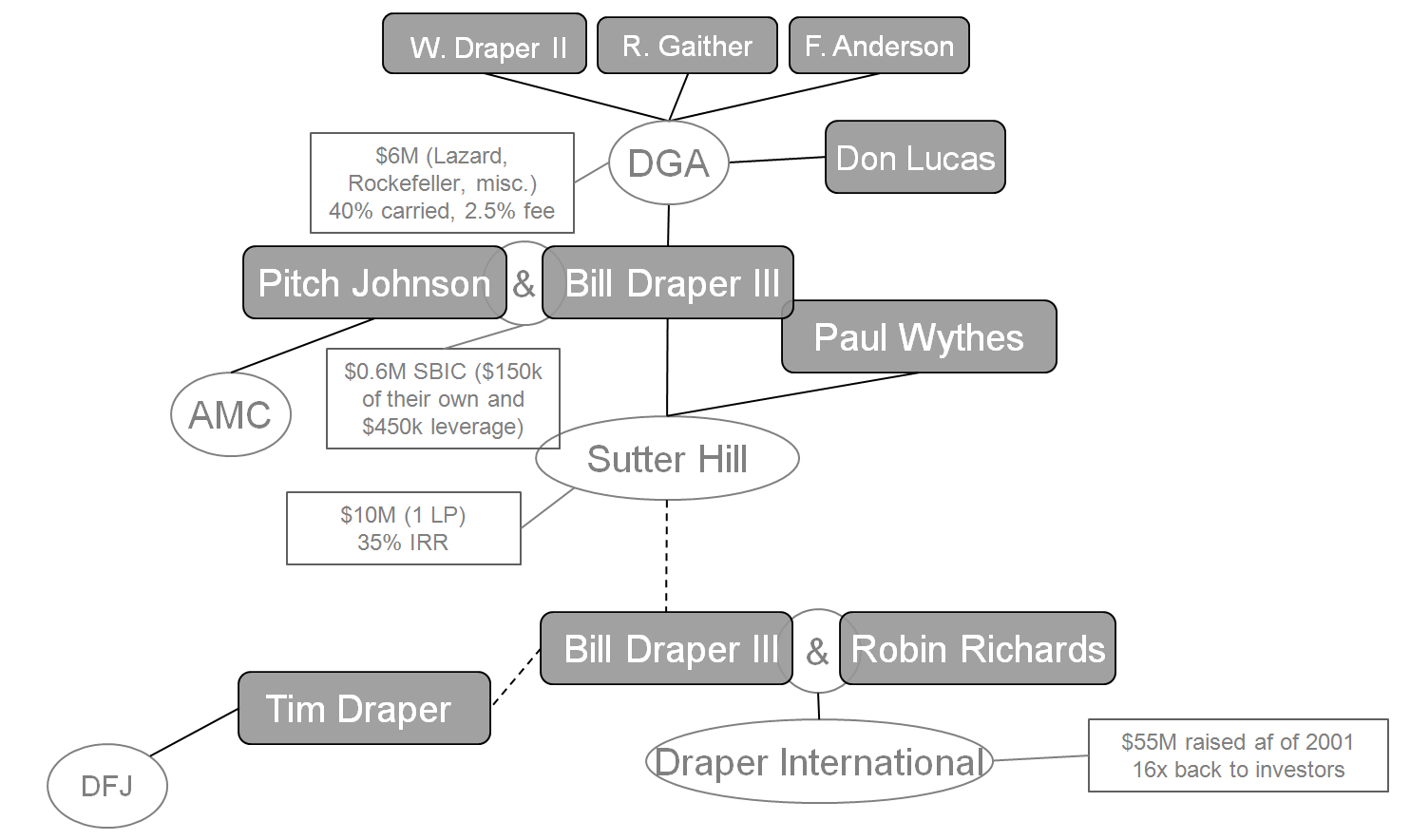

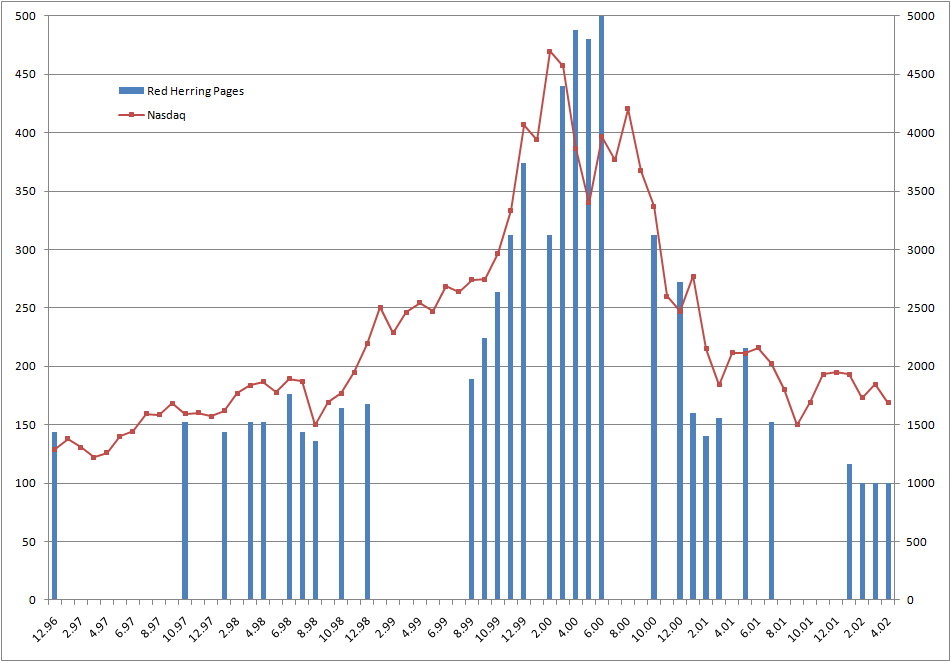

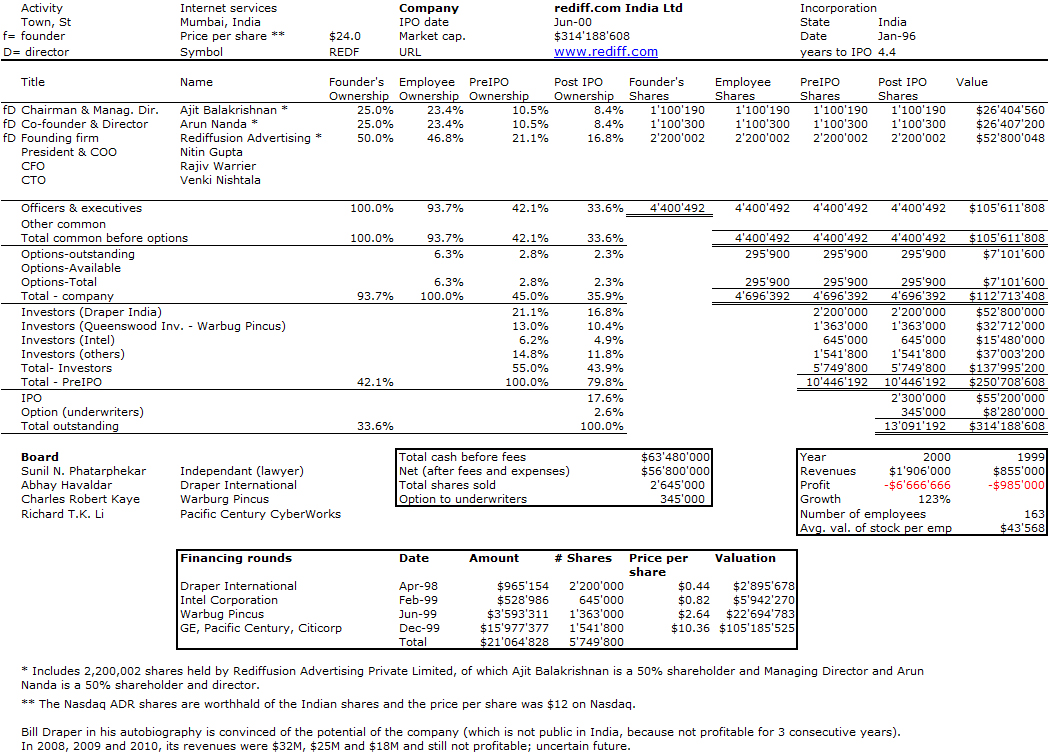

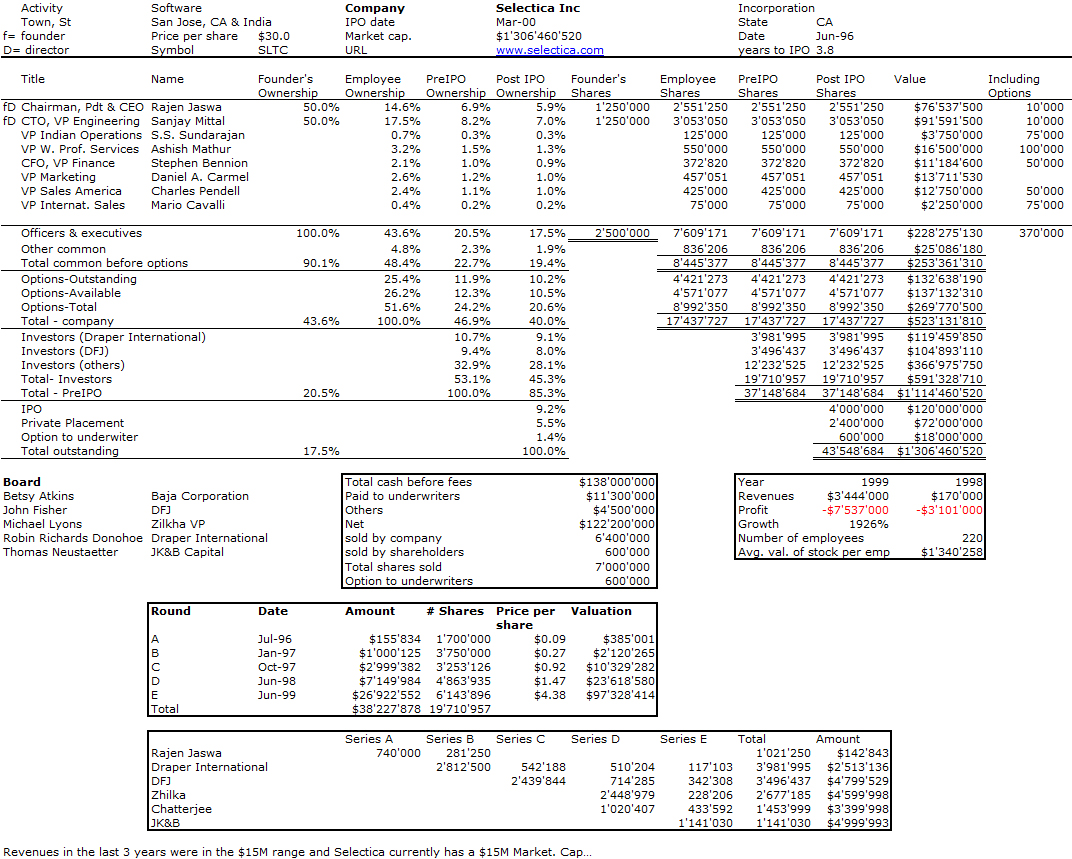

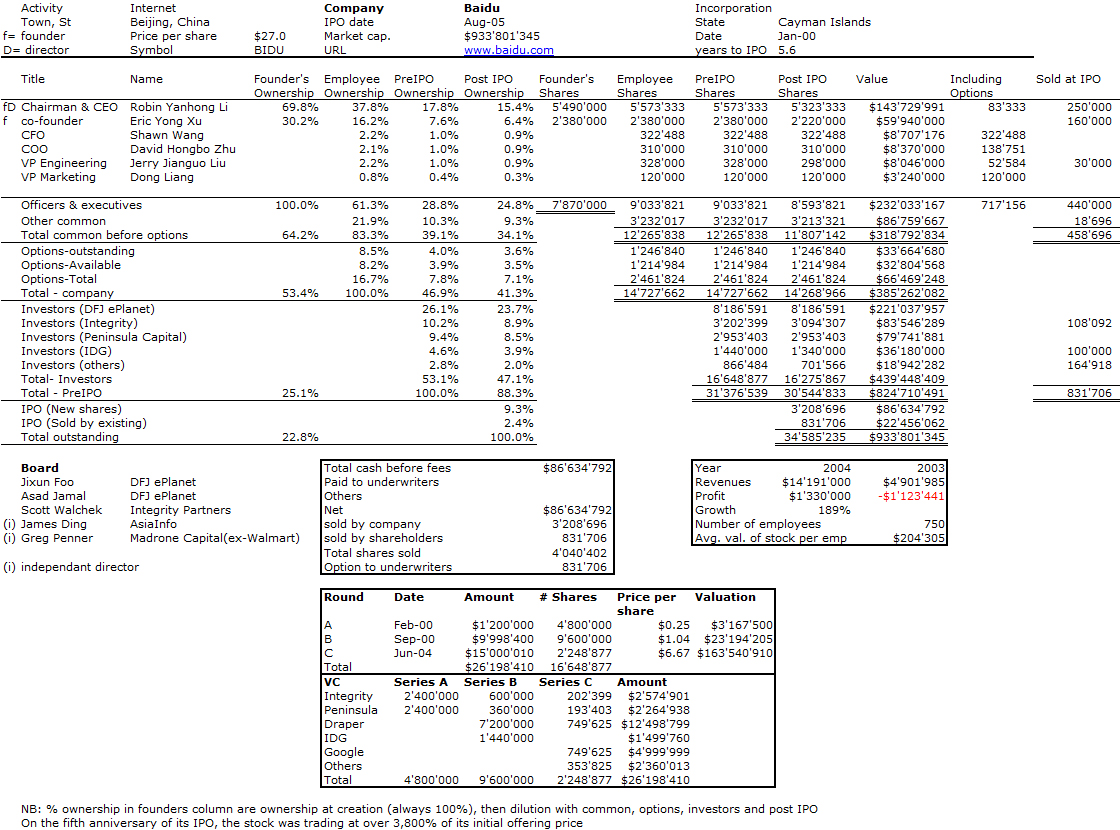

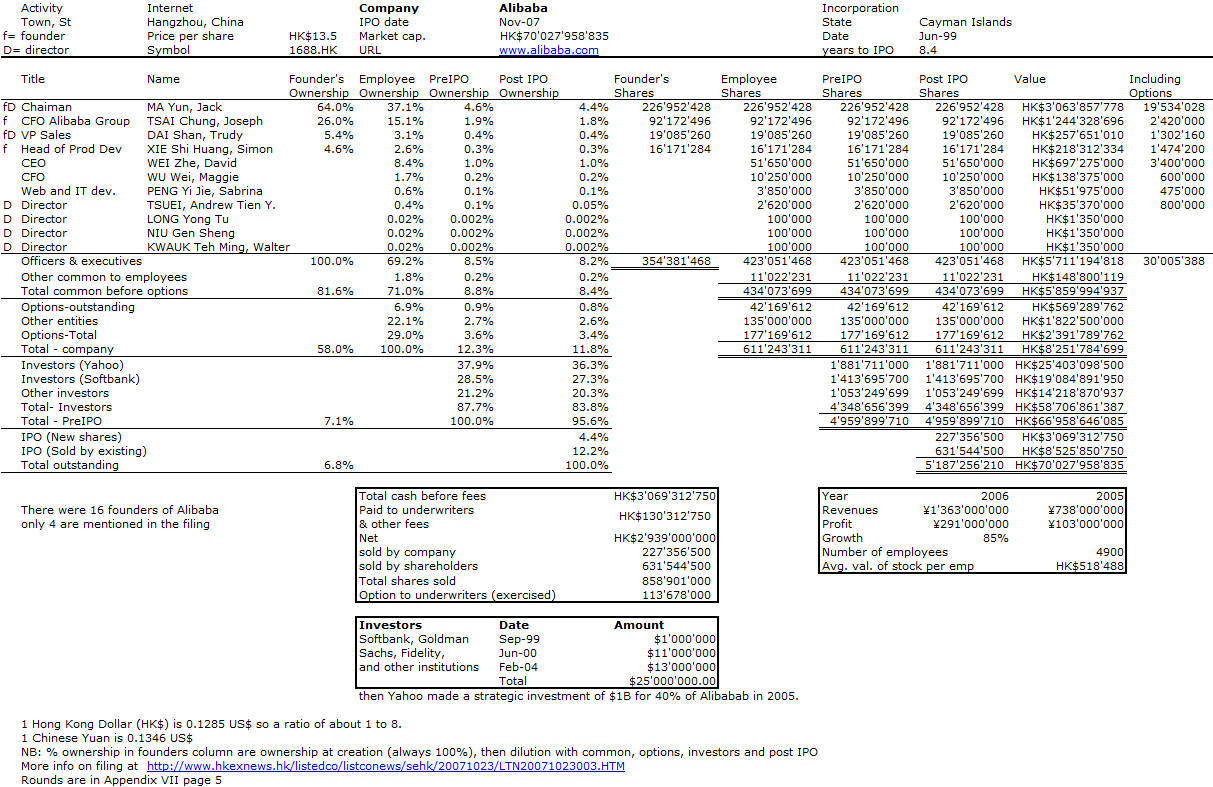

I also found interesting two figures: