Twelve years ago, I had a post entitled Obama. Such an important day at the time.

Today maybe as important…

This was posted on Nov 5, 2008…

Twelve years ago, I had a post entitled Obama. Such an important day at the time.

Today maybe as important…

This was posted on Nov 5, 2008…

Rarely have I read two articles giving a vision as close apparently of the challenges and issues of the future of the planet as I’ll mention in a moment. I say apparently, because behind some consistencies about a confident vision of the future, lie fairly fundamental differences about the challenges.

But I will allow myself a digression before commenting these tow articles. A third article was published on a very different subject in the paper edition the New Yorker dated Oct. 10, 2016 – again apparently as it deals about the past and the present! It is entitled He’s Back. This article reminded me that my two most important readings in 2016 (and perhaps in the 21st century) are those that I mentioned in the post Has the world gone crazy? Maybe…, namely the tremendous Capital in the 21st Century by Thomas Piketty and the no less remarkable In the disruption – How not to go crazy? by Bernard Stiegler. I need to give the title of the digital edition that might hopefully inspire you to discover Karl Marx, Yesterday and Today – The nineteenth-century philosopher’s ideas may help us to understand the economic and political inequality of our time.

Back to the point that motivates this post. Barack Obama has just published in The Economist a short text in which he describes the challenges ahead. This is a brilliant article. It also creates a certain mystery for me around the American president. Is he very well surrounded by knowledgeable advisors and / or has he become interested so deeply in topics to the point of finding the time to write (I should say to describe) himself the world’s complexity. An absolute must-read: The Way Ahead.

In comparison, Adding a Zero in the same Oct. 10 New Yorker – entitled in the electronic version Sam Altman’s Manifest Destiny with however an identical subtitle Is the head of Y Combinator fixing the world, or try trying to take over Silicon Valley? This very long article describes perfectly the reasons why we can equally love and hate Silicon Valley. It is a Pharmakon (both a remedy and a poison according Stiegler’s words). I encourage you to read it too, but your priority should go to reading Barack Obama.

I’ll try to explain myself. Obama has tried a lot and has not been so successful, but there has a consistency in his acts, I think. In The Economist, he wrote: “Fully restoring faith in an economy where hardworking Americans can get ahead requires addressing four major structural challenges: boosting productivity growth, combating rising inequality, ensuring that everyone who wants a job can get one and building a resilient economy that’s primed for future growth.” Obama is an optimist and a moderate. All but a revolutionary. There is a beautiful sentence in the middle of the article: “The presidency is a relay race, requiring each of us to do our part to bring the country closer to its highest aspirations.” The highest aspirations. I sincerely believe that is why Obama deserved the Nobel Peace Prize despite all the difficulties of his task.

Silicon Valley has the same optimism and the same belief in technological progress and well-being that it brings (or may bring). Growth is a mantra. Sam Altman is no exception to the rule. Here are some examples: “We had limited our projected revenue to thirty million dollars,” Chesky [the founder and CEO of Airbnb] said. “Sam said, ‘Take all the “M”s and make them “B”s.’ ” Altman recalls telling them, “Either you don’t believe everything you said in the rest of the deck, or you’re ashamed, or I can’t do math.” [Page 71] then a little further “It is one of the rarer mistakes to make, trying to be too lean,” Altman said, “Don’t worry about a competitor until they’re beating you in the market,” … “Competitors are one of the last monsters that haunt your dreams.”… “Always think about adding one more zero to whatever you’re doing, but never think beyond that.” [Page 75]

Illustration by R. Kikuo Johnson

Illustration by R. Kikuo Johnson

Clearly risk taking steps accordingly: In a class that Altman taught at Stanford in 2014, he remarked that the formula for estimating a startup’s chance of success is “something like Idea times Product times Execution times Team times Luck, where Luck is a random number between zero and ten thousand.” [Page 70] The strategy of accelerators such as Y Combinator looks pretty simple: “What we ask of startups is very simple but very hard to do. One, make something people want”—a phrase of Graham’s, which is emblazoned on gray T-shirts for the founders—“and, two, all you should be doing is talking to your customers and building stuff.” [Page 73] The result of this strategy lies in the performance of these acceleration mechanisms: A 2012 study of North American accelerators found that almost half of them had failed to produce a single startup that went on to raise venture funding. While a few accelerators, such as Tech Stars and 500 Startups, have a handful of alumni worth hundreds of millions of dollars, Y Combinator has graduates worth at least a billion—and it has eleven of them. [Page 71] but Altman is dissatisfied: Venture capitalists believe that their returns follow a “power law,” by which ninety per cent of their profits come from one or two companies. This means that they secretly hope the other startups in their portfolio fail fast, rather than staggering onward as resource-consuming “zombies.” Altman pointed out that only a fifth of YC companies have failed, and said, “We should be taking crazier risks, so that our failure rate would be as high as ninety per cent. [Page 83]

“Under Sam, the level of YC’s ambition has gone up 10x.” Paul Graham, who was leaving soon after the dinner for a sabbatical year in England, told me that Altman, by precipitating progress in “curing cancer, fusion, supersonic airliners, A.I.,” was trying to comprehensively revise the way we live: “I think his goal is to make the whole future.” [Page 70] Recently, YC began planning a pilot project to test the feasibility of building its own experimental city. It would lie somewhere in America, or perhaps abroad, and would be optimized for technological solutions: it might, for instance, permit only self-driving cars. “It could be a college town built out of YC, the university of the future,” Altman said. “A hundred thousand acres, fifty to a hundred thousand residents. We crowdfund the infrastructure and establish a new and affordable way of living around concepts like ‘No one can ever make money off of real estate.’ ” He emphasized that it was just an idea—but he was already looking at potential sites. You could imagine this metropolis as an exemplary post-human city-state, run on A.I. — a twenty-first-century Athens — or as a gated community for the élite, a fortress against the coming chaos. [Page 83] YC’s optimism goes very far: “We’re good at screening out assholes,” Graham told me. “In fact, we’re better at screening out assholes than losers. […] Graham wrote an essay, “Mean People Fail,” in which—ignoring such possible counterexamples as Jeff Bezos and Larry Ellison—he declared that “being mean makes you stupid” and discourages good people from working for you. Thus, in startups, “people with a desire to improve the world have a natural advantage.” Win-win. [Page 73]

Altman is not devoid of social conscience, well not quite. “If you believe that all human lives are equally valuable, and you also believe that 99.5 per cent of lives will take place in the future, we should spend all our time thinking about the future.” [He looks at] the consequences of innovation as a systems question. The immediate challenge is that computers could put most of us out of work. Altman’s fix is YC Research’s Basic Income project, a five-year study, scheduled to begin in 2017, of an old idea that’s suddenly in vogue: giving everyone enough money to live on. … YC will give as many as a thousand people in Oakland an annual sum, probably between twelve thousand and twenty-four thousand dollars. [Page 81] But the conclusion of the article is perhaps the most important sentence of the whole article, which brings us back to Obama’s moderation. Comparing himself to another wildly ambitious project creator, Altman says, “At the end of his life, he did also say that it should all be sunk to the bottom of the ocean. There’s something worth thinking about in there.”

Ultimately, Obama, Altman, Marx, Piketty and Stiegler all have the same faith in the future and progress and the same concern about the growing inequalities. Altman seems to be the only one (together with many people in Silicon Valley) to believe that disruptions and revolutions will solve everything, while the others see their destructive features and prefer a moderate and progressive evolution. Over the years, I tend to prefer moderation too…

PS: if you would not have enough reading, then continue with the series of interviews President Obama gave to Wired: Now Is the Greatest Time to Be Alive.

Time to finish my account of In the Plex after already four posts. Chapter 5 is about Google in the mobile and in the video. Chapter 6 is about China, a very interesting chapter about Google’s moral dilemmas. Chapter 7 is about the relationships with government.

These chapters show Google is now a mature and serious company, with exceptions:

The keynote did end on a high note. Page had insisted that there be a question period, almost as if he were running a Google TGIF. This was almost unheard of in CES keynotes. The people at Google in charge of the speech came up with an inspired idea: they spent a bundle to book the comedian Robin Williams (a huge Google fan) as Page’s sidekick for the Q and A. The conceit was that Williams would be a human Google. The comic’s manic improvisations made people instantly forget the awkwardness of Page’s presentation. The funniest moment came when a French reporter began to ask a tough question of Page but could not finish due to Williams’s relentless, politically indefensible, and utterly hilarious mocking of the man’s accent and nationality. The unfortunate Frenchman sputtered with rage. The moment fit Google perfectly: corporate presentation turned as anarchic as a Marx Brothers skit. [pages 246-247]

“Sergey and Larry are not kids anymore,” Eric Schmidt noted in early 2010. “They are in their mid-thirties, accomplished senior executives in our industry. When I showed up, they were founder kids— very, very smart, but without the operating experience they have now. It’s very important to understand that they are learning machines and that ten years after founding the company, they’re much more experienced than you’ll ever imagine.” From Schmidt’s comments, it was reasonable to wonder when the inevitable would occur—when Larry Page, now middle-aged and officially seasoned, might once again become Google’s CEO, a job he had been reluctant to cede and gave up only at the VC’s insistence. When asked directly if he was eager to reassume the role, Page refused to engage. “That’s all speculation,” he said. [Page 254]

And the inevitable brain drain would follow

Google didn’t stop recruiting the best people it could find, especially engineers. In fact, the effort became more urgent because there were vacancies at Google created by valued employees who either joined tech firms that were newer and more nimble than Google or started their own companies. And every so often, an early Googler would simply retire on his or her stock-option fortune. The defections included high-ranking executives and—perhaps scarier to the company—some of its smartest young engineers. The press labeled the phenomenon Google’s “brain drain.” Sheryl Sandberg, who had built up the AdWords organization, left to become the chief operating officer at Facebook. Tim Armstrong left his post as head of national sales to become CEO of AOL. (“We spent all of Monday convincing him to stay,” said the grim Sergey Brin at that next week’s TGIF, expressing well wishes toward its valuable sales manager.) Gmail inventor Paul Buchheit joined with Bret Taylor (who had been product manager for Google Maps) to start a company called FriendFeed. Of the eighteen APMs—Google’s designated future leaders—who had circled the globe with Marissa Mayer in the summer of 2007, fewer than half were still with the company two years later. All of them left with nothing but respect and gratitude for Google—but felt that more exciting opportunities lay elsewhere. Bret Taylor, while specifying that he cherished his time at Google, later explained why he’d left. “When I started at the company, I knew everyone there,” he said. “There’s less of an entrepreneurial feel now. You have less input on the organization as a whole.” When he announced his departure, a procession of executives came to his desk asking him to reconsider. “I didn’t know Google had so many VPs,” he said. But he’d made his mind up. [Page 259]

Really reaching maturity?

Eric turned to him and said, “Okay, Larry, what do you want to do? How fast do you want to grow?” “How many engineers does Microsoft have?” asked Page. About 25,000, Page was told. “We should have a million,” said Page. Eric, accustomed to Page’s hyperbolic responses by then, said, “Come on, Larry, let’s be real.” But Page had a real vision: just as Google’s hardware would be spread around the world in hundreds of thousands of server racks, Google’s brainpower would be similarly dispersed, revolutionizing the spread of information while speaking the local language. [Page 271]

Failure in China

China has been Google deepest failure. Despite efforts and (too much?) compromise, Google has never really succeeded in China. Chapter 6 is another must read. Brin who has always been the most sensitive to human rights “went as far” as abstaining at a shareholder meeting.

During the Google annual shareholders meeting on May 8, 2008, Brin took the rare step of separating himself from Page and Schmidt on the issue. Shareholders unhappy with Google censorship in China had forwarded two proposals to mitigate the misdeed. The first, organized by Amnesty International and submitted by the New York state pension fund, which owned 2 million shares of Google, demanded a number of steps before the company engaged in activities that suppressed freedom. The second would force the board of directors to set up a committee focusing on human rights. Google officially opposed the proposals, and with a voting structure that weighted insider shares ten times as heavily as those owned by outside investors, the proposals were easily defeated. But Brin abstained, sending a signal—though maybe only to himself—that his conscience would no longer permit him to endorse the company’s actions in China unreservedly. When shareholders had a chance to question Google’s leaders, Brin explained himself: “I agree with the spirit of both of these, particularly in human rights, freedom of expression, and freedom to receive information.” He added that he was “pretty proud of what we’ve been able to achieve in China” and that Google’s activities there “honored many of our principles.” But not all.

It was a clear sign that Brin no longer believed in Google’s China strategy. Another signal was the fact that after Google China was established, and despite Kai-Fu Lee’s urging, neither Brin nor Page ever crossed the threshold of their most important engineering center abroad. Even in mid-2009, when the pair decided to fly their private Boeing 767-200 to the remote Eniwetok Atoll in the Pacific Ocean to view a solar eclipse and Brin used the occasion to drop in on Google Tokyo, they skipped China. Still, Google was reluctant to defy the government of China. There was still hope that things would turn around. In addition, its business operations in China were doing well. Though it had far to go to unseat Baidu, Google was clearly in second place and more than holding its own. In maps and mobile Google was a leader. In the world’s biggest Internet market, Google was in a better position than any other American company. [Page 305]

Finally…

“The security incident, because of its political nature, just caused us to say ‘Enough’s enough,’” says Drummond. The next day Drummond wrote a blog item explaining Google’s decision. It was called “A New Approach to China.” He outlined the nature of the attack on Google and explained that it had implications far beyond a security breach; it hit the heart of a global debate about free speech. Then he dropped Google’s bombshell:

These attacks and the surveillance they have uncovered— combined with the attempts over the past year to further limit free speech on the web—have led us to conclude that we should review the feasibility of our business operations in China. We have decided we are no longer willing to continue censoring our results on Google.cn, and so over the next few weeks we will be discussing with the Chinese government the basis on which we could operate an unfiltered search engine within the law, if at all. We recognize that this may well mean having to shut down Google.cn, and potentially our offices in China.

On January 12, Google published the Drummond essay on its blog. The news spread through Mountain View like an earthquake. Meetings all over the campus came to a dead stop as people looked at their laptops and read how Google was no longer doing the dirty work of the Chinese dictatorship. “I think a whole generation of Googlers will remember exactly where they were when that blog item appeared,” says one product manager, Rick Klau. [Page 311]

And according to Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Google_China “As of November 2013, its search share has declined to 1.7% from its August 2009 level of 36.2%”.

Google and Politics

By late 2007, Barack Obama already had an impressive Google following. Andrew McLaughlin, Google’s policy chief, was advising the senator on tech issues. The product manager for Blogger, Rick Klau, had lived in Illinois and had operated Obama’s blog when the politician ran for the Senate (he’d even let Obama use his house for a fundraiser). Eric Schmidt was the candidate’s official host. [Page 316]

In an ideal world: “I think of them as Internet values. They’re values of openness, they’re values of participation, they’re values of speed and efficiency. Bringing those tools and techniques into government is vital.” [Page 322]

But the reality is tougher: “The job was frustrating. Google hadn’t been perfect, but people got things done—because they were engineers. One of the big ideas of Google was that if you gave engineers the freedom to dream big and the power to do it—if you built the whole operation around their mindset and made it clear that they were in charge—the impossible could be accomplished. But in the government, even though Stanton’s job was to build new technologies and programs, “I didn’t meet one engineer,” she says. “Not one software engineer who works for the United States government. I’m sure they exist, but I haven’t met any. At Google I worked with people far smarter and creative than me, and they were engineers, and they always made everyone else look good. They’re doers. We get stuck in the government because we really don’t have a lot of those people.” [Page 323]

Final thought: Is Google evil?

This is a debate I often have with friends and colleagues. You’ve seen my fascination and I love the way Google tries, explores and changes our world. Still, one may see things differently. As an example, here are some quotes about Google Print.

Maybe the care that Google took to hide its activity was an early indicator of trouble to come. If the world would so eagerly welcome the fruits of Ocean [Google Print code name], what was the need for such stealth? The secrecy was yet another expression of the paradox of a company that sometimes embraced transparency and other times seemed to model itself on the NSA. In other areas, Google had put its investments into the public domain, like the open-source Android and Chrome operating systems. And as far as user information was concerned, Google made it easy for people not to become locked into using its products. […] It would seem that book scanning was a good candidate for similar transparency. If Google had a more efficient way to scan books, sharing the improved techniques could benefit the company in the long run—inevitably, much of the output would find its way onto the web, bolstering Google’s indexes. But in this case, paranoia and a focus on short-term gain kept the machines under wraps. “We’ve done a ton of work to try to make those machines an order of magnitude better,” AMac said. “That does give us an advantage in terms of scanning rate and cost, and we actually want to have that advantage for a while.” Page himself dismissed the argument that sharing Google’s scanner technology would help the business in the long run, as well as benefit society. “If you don’t have a reason to talk about it, why talk about it?” he responded. “You’re running a business, and you have to weigh [exposure] against the downside, which can be significant.” [Page 354-55]

But not all of the publishers found Google charming. Jack Romanos, then CEO of Simon & Schuster, later complained to New York’s John Heilemann about Google’s “innocent arrogance” and “holier-than-thou” attitude. “One minute they’re pretending to be all idealistic, talking about how they’re only in this to expand the world’s knowledge, and the next they’re telling you that you’re going to have to do it their way or no way at all.” [Page 357]

[There] was the conviction that in a multimillion-dollar enterprise such as Book Search it was unconscionable for authors and publishers not to be paid. After the debate, Aiken laid out the essence of his group’s rationale to an Authors Guild member who told him that he’d like his books discoverable by Google. “Don’t you understand?” Aiken said. “These people in Silicon Valley are billionaires, and they’re making money off you!” [Page 360]

Google has missed opportunities such as in social networking. Orkut, then Wave, Dodgeball, Buzz replaced by Google + were more beta tests and then a reaction to Facebook. Google often tries things without much effort and checks if traction comes or not. But its ambition has not really slowed down: “Michigan had already begun digitizing some of its work. “It was a project that our librarians predicted would take one thousand years,” Coleman later said in a speech. “Larry said that Google would do it in six.” [Page 352]

Indeed Page had dreamed about digitizing books already at Stanford and in the early days of Google, he began playing with scanners, helped by Marissa Meyer: “The first few times around were kind of sloppy, because Marissa’s thumb kept getting in the way. Larry would say, “Don’t go too fast … don’t go too slow.” It had to be a rate that someone could maintain for a long time—this was going to scale, remember, to every book ever written. They finally used a metronome to synchronize their actions. After some practice, they found that they could capture a 300- page book such as Startup in about forty-two minutes, faster than they expected. Then they ran optical character recognition (OCR) software on the images and began searching inside the book. Page would open the book to a random page and say, “This word—can you find it?” Mayer would do a search to see if she could. It worked. Presumably, a dedicated machine could work faster, and that would make it possible to capture millions of books. How many books were ever printed? Around 30 million? Even if the cost was $10 a book, the price tag would only be $300 million. That didn’t sound like too much money for the world’s most valuable font of knowledge.” [Page 360] (Google Print is now Google Books – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Google_Books)

In 2011, Page ambition is still there. He is now the CEO. In late 2010, “Sergey Brin had repeated the sentiment: ‘We want Google to be the third half of your brain’ “. [Page 386]

“I just feel like people aren’t working enough on impactful things,” Page said. “People are really afraid of failure on things, and so it’s hard for them to do ambitious stuff. And also, they don’t realize the power of technological solutions to things, especially computers.” He went on to rhapsodize about big goals like driving down the price of electricity to three cents a watt—it really wouldn’t take all that much in resources to launch a project to do that, he opined. In general, society wasn’t taking on enough big projects, according to Page. At Google, he said, when his engineers undertook a daunting, cutting-edge project, there were huge benefits, even if the stated goal of the project wasn’t accomplished. He implied that even at Google there wasn’t enough of that ambition. “We’re in the really early stages of all of this,” he said. “And we’re not yet doing a good job getting the kinds of things we’re trying to do to happen quickly and at scale.” [Page 387]

I just finished In the Plex and I kind of feel sad. It is a book I wish I would never have finished reading. I have now read four books about Google. In fact, we are far from the end. It may even be just the beginning as Page and Brin seem to believe and I will probably read other books abotu Google in the future. As good as this one? Only the future will tell… but i will finish here with a 2007 post.

What have these 4 things in common? I am not sure. But in the last 12 hours, I had to put this 4 things together. My professional life is about technology, but I am not a technophile. I do not have a smart phone. But I like people and I strangely rediscovered it through high-tech entrepreneurship. There are many, many more important things. I will give you two examples with Bruce Springsteen and Jonathan Franzen, two known supporters of Barack Obama, whom I have mentioned a couple of times here. These are just two (therefore three) examples of why it is possible to like America… follow me, you don’t have to agree.

(Let me just add 5 minutes after publishing this article that we are on July 4!)

Yesterday, I was in Geneva for one of the best concerts of my life. The Boss and his sixteen musicians gave a nearly 3 hour-long show with a generosity I had never seen on stage. I did not know about his “sign requests”. His fans showed him signs with song titles and he picked a few, which he would later sing. Not the kind of music machines I am often used to experience. A kid went on stage and sang alone for a while. This was unique too. He is 63-year old and has the energy of a youngster, the generosity of a wise man. No naiveness. “We have a job to make here tonight.” What a job! I found a site which gave a short account including the songs he chose yesterday (including the signed ones – see in the end). Springsteen belongs to the group of people which show why we can love America.

I also like Jonathan Franzen. I may have read all his writings, The Corrections remains my favorite one. I am currently reading his latest essays. He also shows suffering, misery, hardship in America. A different kind of suffering, but in the end, it is probably the same. Americas is great when it shows its weaknesses. But neither Sprinsteen nor Franzen are depressing, because they are generous, they are passionate. I don’t see any cynism. Hopefully, I am not naive. In one of his latest essays, a commencement address at Kenyon College, he links technology and love… The title is PAIN WON’T KILL YOU and in the NYT he made another version entitled Liking Is for Cowards. Go for What Hurts.

Here is the NYT full version. I think it is worth reading it. But you can use the two previous web links too. I will try to provide my French version later…

*************************

Liking Is for Cowards. Go for What Hurts.

By JONATHAN FRANZEN

Published: May 28, 2011

A COUPLE of weeks ago, I replaced my three-year-old BlackBerry Pearl with a much more powerful BlackBerry Bold. Needless to say, I was impressed with how far the technology had advanced in three years. Even when I didn’t have anybody to call or text or e-mail, I wanted to keep fondling my new Bold and experiencing the marvelous clarity of its screen, the silky action of its track pad, the shocking speed of its responses, the beguiling elegance of its graphics.

I was, in short, infatuated with my new device. I’d been similarly infatuated with my old device, of course; but over the years the bloom had faded from our relationship. I’d developed trust issues with my Pearl, accountability issues, compatibility issues and even, toward the end, some doubts about my Pearl’s very sanity, until I’d finally had to admit to myself that I’d outgrown the relationship.

Do I need to point out that — absent some wild, anthropomorphizing projection in which my old BlackBerry felt sad about the waning of my love for it — our relationship was entirely one-sided? Let me point it out anyway.

Let me further point out how ubiquitously the word “sexy” is used to describe late-model gadgets; and how the extremely cool things that we can do now with these gadgets — like impelling them to action with voice commands, or doing that spreading-the-fingers iPhone thing that makes images get bigger — would have looked, to people a hundred years ago, like a magician’s incantations, a magician’s hand gestures; and how, when we want to describe an erotic relationship that’s working perfectly, we speak, indeed, of magic.

Let me toss out the idea that, as our markets discover and respond to what consumers most want, our technology has become extremely adept at creating products that correspond to our fantasy ideal of an erotic relationship, in which the beloved object asks for nothing and gives everything, instantly, and makes us feel all powerful, and doesn’t throw terrible scenes when it’s replaced by an even sexier object and is consigned to a drawer.

To speak more generally, the ultimate goal of technology, the telos of techne, is to replace a natural world that’s indifferent to our wishes — a world of hurricanes and hardships and breakable hearts, a world of resistance — with a world so responsive to our wishes as to be, effectively, a mere extension of the self.

Let me suggest, finally, that the world of techno-consumerism is therefore troubled by real love, and that it has no choice but to trouble love in turn.

Its first line of defense is to commodify its enemy. You can all supply your own favorite, most nauseating examples of the commodification of love. Mine include the wedding industry, TV ads that feature cute young children or the giving of automobiles as Christmas presents, and the particularly grotesque equation of diamond jewelry with everlasting devotion. The message, in each case, is that if you love somebody you should buy stuff.

A related phenomenon is the transformation, courtesy of Facebook, of the verb “to like” from a state of mind to an action that you perform with your computer mouse, from a feeling to an assertion of consumer choice. And liking, in general, is commercial culture’s substitute for loving. The striking thing about all consumer products — and none more so than electronic devices and applications — is that they’re designed to be immensely likable. This is, in fact, the definition of a consumer product, in contrast to the product that is simply itself and whose makers aren’t fixated on your liking it. (I’m thinking here of jet engines, laboratory equipment, serious art and literature.)

But if you consider this in human terms, and you imagine a person defined by a desperation to be liked, what do you see? You see a person without integrity, without a center. In more pathological cases, you see a narcissist — a person who can’t tolerate the tarnishing of his or her self-image that not being liked represents, and who therefore either withdraws from human contact or goes to extreme, integrity-sacrificing lengths to be likable.

If you dedicate your existence to being likable, however, and if you adopt whatever cool persona is necessary to make it happen, it suggests that you’ve despaired of being loved for who you really are. And if you succeed in manipulating other people into liking you, it will be hard not to feel, at some level, contempt for those people, because they’ve fallen for your shtick. You may find yourself becoming depressed, or alcoholic, or, if you’re Donald Trump, running for president (and then quitting).

Consumer technology products would never do anything this unattractive, because they aren’t people. They are, however, great allies and enablers of narcissism. Alongside their built-in eagerness to be liked is a built-in eagerness to reflect well on us. Our lives look a lot more interesting when they’re filtered through the sexy Facebook interface. We star in our own movies, we photograph ourselves incessantly, we click the mouse and a machine confirms our sense of mastery.

And, since our technology is really just an extension of ourselves, we don’t have to have contempt for its manipulability in the way we might with actual people. It’s all one big endless loop. We like the mirror and the mirror likes us. To friend a person is merely to include the person in our private hall of flattering mirrors.

I may be overstating the case, a little bit. Very probably, you’re sick to death of hearing social media disrespected by cranky 51-year-olds. My aim here is mainly to set up a contrast between the narcissistic tendencies of technology and the problem of actual love. My friend Alice Sebold likes to talk about “getting down in the pit and loving somebody.” She has in mind the dirt that love inevitably splatters on the mirror of our self-regard.

The simple fact of the matter is that trying to be perfectly likable is incompatible with loving relationships. Sooner or later, for example, you’re going to find yourself in a hideous, screaming fight, and you’ll hear coming out of your mouth things that you yourself don’t like at all, things that shatter your self-image as a fair, kind, cool, attractive, in-control, funny, likable person. Something realer than likability has come out in you, and suddenly you’re having an actual life.

Suddenly there’s a real choice to be made, not a fake consumer choice between a BlackBerry and an iPhone, but a question: Do I love this person? And, for the other person, does this person love me?

There is no such thing as a person whose real self you like every particle of. This is why a world of liking is ultimately a lie. But there is such a thing as a person whose real self you love every particle of. And this is why love is such an existential threat to the techno-consumerist order: it exposes the lie.

This is not to say that love is only about fighting. Love is about bottomless empathy, born out of the heart’s revelation that another person is every bit as real as you are. And this is why love, as I understand it, is always specific. Trying to love all of humanity may be a worthy endeavor, but, in a funny way, it keeps the focus on the self, on the self’s own moral or spiritual well-being. Whereas, to love a specific person, and to identify with his or her struggles and joys as if they were your own, you have to surrender some of your self.

The big risk here, of course, is rejection. We can all handle being disliked now and then, because there’s such an infinitely big pool of potential likers. But to expose your whole self, not just the likable surface, and to have it rejected, can be catastrophically painful. The prospect of pain generally, the pain of loss, of breakup, of death, is what makes it so tempting to avoid love and stay safely in the world of liking.

And yet pain hurts but it doesn’t kill. When you consider the alternative — an anesthetized dream of self-sufficiency, abetted by technology — pain emerges as the natural product and natural indicator of being alive in a resistant world. To go through a life painlessly is to have not lived. Even just to say to yourself, “Oh, I’ll get to that love and pain stuff later, maybe in my 30s” is to consign yourself to 10 years of merely taking up space on the planet and burning up its resources. Of being (and I mean this in the most damning sense of the word) a consumer.

When I was in college, and for many years after, I liked the natural world. Didn’t love it, but definitely liked it. It can be very pretty, nature. And since I was looking for things to find wrong with the world, I naturally gravitated to environmentalism, because there were certainly plenty of things wrong with the environment. And the more I looked at what was wrong — an exploding world population, exploding levels of resource consumption, rising global temperatures, the trashing of the oceans, the logging of our last old-growth forests — the angrier I became.

Finally, in the mid-1990s, I made a conscious decision to stop worrying about the environment. There was nothing meaningful that I personally could do to save the planet, and I wanted to get on with devoting myself to the things I loved. I still tried to keep my carbon footprint small, but that was as far as I could go without falling back into rage and despair.

BUT then a funny thing happened to me. It’s a long story, but basically I fell in love with birds. I did this not without significant resistance, because it’s very uncool to be a birdwatcher, because anything that betrays real passion is by definition uncool. But little by little, in spite of myself, I developed this passion, and although one-half of a passion is obsession, the other half is love.

And so, yes, I kept a meticulous list of the birds I’d seen, and, yes, I went to inordinate lengths to see new species. But, no less important, whenever I looked at a bird, any bird, even a pigeon or a robin, I could feel my heart overflow with love. And love, as I’ve been trying to say today, is where our troubles begin.

Because now, not merely liking nature but loving a specific and vital part of it, I had no choice but to start worrying about the environment again. The news on that front was no better than when I’d decided to quit worrying about it — was considerably worse, in fact — but now those threatened forests and wetlands and oceans weren’t just pretty scenes for me to enjoy. They were the home of animals I loved.

And here’s where a curious paradox emerged. My anger and pain and despair about the planet were only increased by my concern for wild birds, and yet, as I began to get involved in bird conservation and learned more about the many threats that birds face, it became easier, not harder, to live with my anger and despair and pain.

How does this happen? I think, for one thing, that my love of birds became a portal to an important, less self-centered part of myself that I’d never even known existed. Instead of continuing to drift forward through my life as a global citizen, liking and disliking and withholding my commitment for some later date, I was forced to confront a self that I had to either straight-up accept or flat-out reject.

Which is what love will do to a person. Because the fundamental fact about all of us is that we’re alive for a while but will die before long. This fact is the real root cause of all our anger and pain and despair. And you can either run from this fact or, by way of love, you can embrace it.

When you stay in your room and rage or sneer or shrug your shoulders, as I did for many years, the world and its problems are impossibly daunting. But when you go out and put yourself in real relation to real people, or even just real animals, there’s a very real danger that you might love some of them.

And who knows what might happen to you then?

Jonathan Franzen is the author, most recently, of “Freedom.” This essay is adapted from a commencement speech he delivered on May 21 at Kenyon College.

*************************

More for myself! (A blog is also my personal journal) Bruce Springsteen in Switzerland: Dedicates ‘Land of Hope and Dreams’ to Nelson Mandela. Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band were back in action again on Wednesday, playing a 26-song, two-hour-and-52-minute show at the Stade de Genève in Geneva, Switzerland. Highlights included “Frankie” which was played for the first time in 2013 and for only the fifth time this tour and the encores started with Bruce playing “The Promise” solo on the piano, “Youngstown” and “Murder Inc.” were also played. It was the first show this tour that “Wrecking Ball” was not played. In the 118 shows so far this tour, three songs still have perfect attendance: “Waitin’ on a Sunny Day,” “Born to Run” and “Dancing in the Dark.” Bruce dedicated “Land of Hope and Dreams,” the final song of the main set, to Nelson Mandela. Show began at 7:40 p.m. local time (six hours ahead of New Jersey)

Set list

1. Shackled and Drawn

2. Badlands

3. Death to My Hometown

4. Out in the Street (sign request)

5. Hungry Heart (sign request)

6. Candy’s Room (sign request)

7. She’s the One

8. Because the Night

9. Spirit in the Night

10. Frankie

11. The River

12. Youngstown

13. Murder Incorporated

14. Darlington County (sign request)

15. Working on the Highway

16. Bobby Jean

17. Waitin’ on a Sunny Day

18. The Rising

19. Land of Hope and Dreams (dedicated to Nelson Mandela)

Encore:

20. The Promise (solo piano)

21. Born in the U.S.A.

22. Born to Run

23. Dancing in the Dark

24. 10th Avenue Freeze-Out

25. American Land

26. Thunder Road (solo acoustic)

Nearly 3 years after my unusual post about Obama, here is a post slightly related. Before digging into the topic, I have to admit I have a huge respect for the American president. Even after watching George Clooney’s The Ides of March and the disappointment expressed by many people, I am intrigued and fascinated by his track record. I should add for the anecdote that I was in Washington in October 2009 when he was award the Nobel Peace Prize and in Silicon Valley in September 2011 when he pronounced his recent speech to the Congress. I also quite liked the Titan Dinner.

The White House recently published TAKING ACTION, BUILDING CONFIDENCE and the second initiative is about entrepreneurship. It is worth reading these dense 6 pages and among other things, it is striking to notice that the USA, “the most entrepreneurial nation on earth” [page 17] is extremely worried about an “increasingly unfavorable environment” and a “fallen optimism”. For these reasons, the report suggests 12 initiatives to “help spur renewed entrepreneurship”. (They are listed at the bottow on this post)

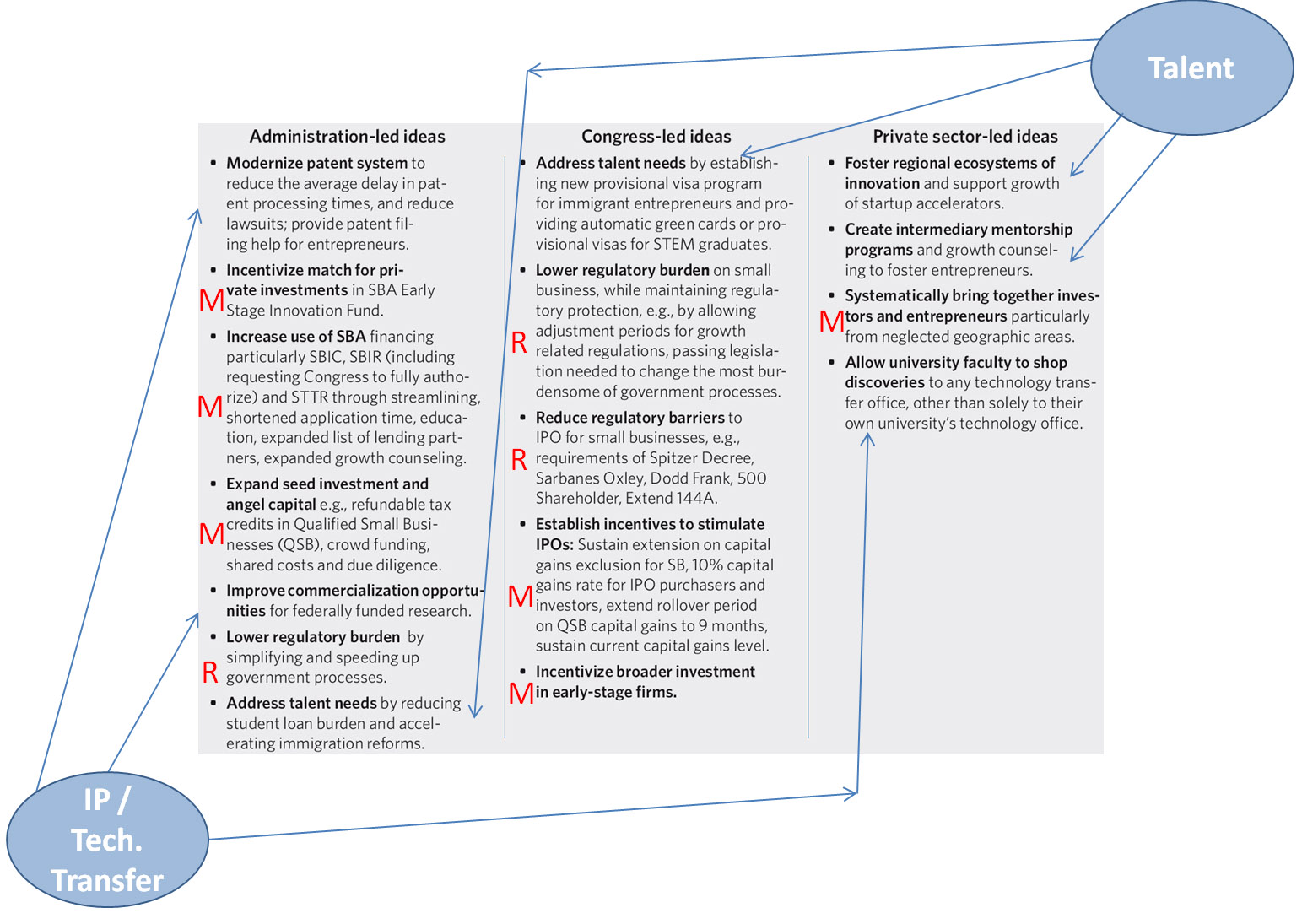

Here is my simplistic vision of the proposals:

– a few are about lowering the barriers, i.e. “changing the Rules”, what I tagged with an “R” below.

– a few more are about enabling more money and investment towards start-ups, tagged with an “M”.

These are classical measures, important and necessary.

What I found very interesting are the other ones:

– three are about Intellectual Property and Technology Transfer, a sign that the patent system might be in trouble

– even more interesting, the last three are about the People, the Talent. They mention the Immigrants and the Mentors.

These are great advice, that we should also look at very seriously in Europe!

Click on the picture to enlarge

Win the Global Battle for Talent

Some of the most iconic American companies were started by immigrant entrepreneurs or the children of immigrant entrepreneurs. Today, however, many of the foreign students completing a STEM degree at a U.S. graduate school return to their home countries and begin competing against American workers. A significant majority of the Jobs Council calls upon Congress to pass reforms aimed directly at allowing the most promising foreign-born entrepreneurs to remain in or relocate to the U.S.

Reduce Regulatory Barriers and Provide Financial Incentives for Firms to Go Public

Lowering the barriers to and cost of IPOs is critical to accessing financing at the later stages of a high growth firms’ expansion. A significant majority of the Jobs Council recommends amending Sarbanes-Oxley and “rightsizing” the effects of the Spitzer Decree and the Fair Disclosure Act to lessen the burdens on high growth entrepreneurial companies.

Enhance Access to Capital for Early Stage Startups as well as Later Stage Growth Companies

The challenging economic environment and skittish investment climate has resulted in investors generally becoming more risk-adverse, and this in turn has deprived many high-growth entrepreneurial companies of the capital they need to expand. The Jobs Council recommends enhancing the economic incentives for investors, so they are more willing to risk their capital in entrepreneurial companies.

Make it Easier for Entrepreneurs to Get Patent-Related Answers Faster

There are concerns among many entrepreneurs that, as written, the recently passed Patent Reform Act advantages large companies, and disadvantages young entrepreneurial companies. The Jobs Council recommends taking specific steps to ensure the ideas from young companies are handled appropriately.

Streamline SBA Financing Access, so More High -Growth Companies Get the Capital they Need to Grow

The SBA has provided early funding for a range of iconic American companies. The Jobs Council recommends that the Administration streamline and shorten application processing with published turnaround times, increase the number of full time employees who perform a training or compliance function, expand the overall list of lending partners, and push Congress to fully authorize SBIR and STTR funding for the long term, rather than for short term re-authorizations.

Expand Seed/Angel Capital

The Jobs Council recommends that the Administration clarify that experienced and active seed and angel investors should not be subject to the regulations that were designed to protect inexperienced investors. We also propose that smaller investors be allowed to use “crowd funding” platforms to invest small amounts in early stage companies.

Make Small Business Administration Funding Easier to Access

The SBA has provided early funding for a range of iconic American companies, including Apple, Costco, and Staples. The Jobs Council recommends that the Administration streamline and shorten application processing with published turnaround times, increase the number of full time employees who perform a training or compliance function, expand the overall list of lending partners, and push Congress to fully authorize SBIR and STTR funding for the long term, rather than for short term re-authorizations.

Enhance Commercialization of Federally Funded Research

The government continues to play a crucial role in investing in the basic research that enables America to be the launchpad for new industries. The Jobs Council recommends that the Administration do more to build bridges between researchers and entrepreneurs, so more breakthrough ideas can move out of the labs and into the commercialization phase.

Address Talent Needs by Reducing Student Loan Burden and Accelerating Immigration Reforms

A large number of recent graduates who aspire to work for a start-up or form a new company decide against it because of the pressing burden to repay their student loans. The Jobs Council recommends that the Administration promote Income-Based Repayment Student Loan Programs for the owners or employees of new, entrepreneurial companies. Additionally, we recommend that the Administration speed up the process for making visa decisions so that talented, foreign-born entrepreneurs can form or join startups in the United States.

Foster Regional Ecosystems of Innovation and Support Growth of Startup Accelerators

There is a significant opportunity to build stronger entrepreneurial ecosystems in regions across the country – and customize each to capitalize on their unique advantages. To that end, the Jobs Council recommends that the private sector support the growth of startup accelerators in at least 30 cities. Private entities should also invest in at least 50 new incubators nationwide, and big corporations should link with startups to advise entrepreneurial companies during their nascent stages.

Expand Programs to Mentor Entrepreneurs

Research consistently shows that a key element of successful enterprises is active mentorship relationships. Yet, if young companies do not have the benefit of being part of an accelerator, they often struggle to find effective mentors to coach them through the challenging, early stages of starting a company. Therefore, the Jobs Council recommends leveraging existing private sector networks to create, expand and strengthen mentorship programs at all levels.

Allow University Faculty to Shop Discoveries to Any Technology Transfer Office

America’s universities have produced many of the great breakthroughs that have led to new industries and jobs. But too often, research that could find market success lingers in university labs. The Jobs Council recommends allowing research that is funded with federal dollars to be presented to any university technology transfer office (not just the one where the research has taken place).

A short quiz: who are the people on the picture?

The answer can be found here. I also tried to do the exercise and you just have to scroll down.

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

…

The first and maybe last time my post has nothing to do with start-ups. But this is just TOO BIG for America and for the Rest of the World.

It just shows everything is possible even if often risky, uncertain. Passion, ambition shall prevail!

Finally here is a picture taken in-mid october in a street of Soho in New York.