From Counterculture to Cyberculture is another recent reading of mine after Making Silicon Valley of a not so recent book. It is subtitled Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism.

Here is a short extract of why the book is important: By the end of the 1960s, some elements of the counterculture, and particularly that segment of it that headed back to the land, had begun to explicitly embrace the systems visions circulating in the research world of the cold war. But how did those two worlds together? How did a social movement devoting to critiquing the technological bureaucracy of the cold war come to celebrate the socio-technical visions that animated that bureaucracy? And how is it that the communitarian ideals of the counterculture should have become melded to computers and computer networks in such a way that thirty years later, the Internet could appear to so many as an emblem of a youthful revolution reborn? [Page 39]

The Whole Earth Catalog

One explanation of this strange phenomenon is Stewart Brand and the Whole Earth Catalog:

Here are some more extracts: “In late 1967 [Stewart Brand and Lois Jennings] moved to Menlo Park where Brand began working at his friend Dick Raymond’s nonprofit educational foundation, the Portola Institute. Founded a year earlier, the Portola Institute housed and helped a variety influential Bay area organizations, including the Briarpatch Society, the Ortega Park Teachers Laboratory, the Farallones Institute, the Urban House, the Simple Living Project, and Big Rock Candy Mountain publishers, as well as its most visible production, the Whole Earth Catalog. As Theodore Roszak has suggested, Portola’s efforts were all designed “to scale down, democratize and humanize our hypertrophic technological society.” When Stewart Brand joined, much of Portola’s energy was directed towards providing computer education in the schools and developing simulation games for the classroom.

[…]

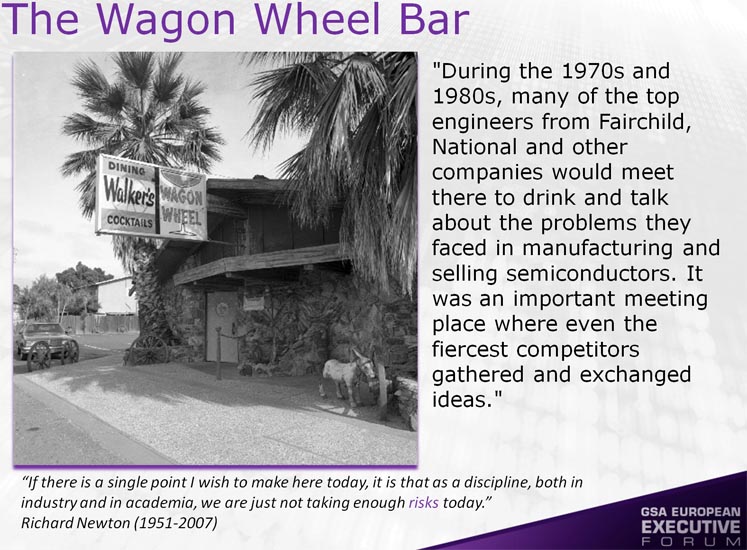

The Portola Institute served as a meeting ground for counterculturalists, academics, and technologists in large part because of its location. Within four blocks of its offices, one could find the office of the Free University – a polyglot self-education project that offered all sorts of courses, ranging from mathematics to encounter groups, usually taught in neighboring homes – and two off-center bookstores (Kepler’s and East-West). A little farther away was the Stanford Research Institute, where Dirk Raymond had worked for a number of years, and not far beyond that, Stanford University. In addition, many of Portola’s members represented multiple communities. Albrecht had worked at Control Data Corporation and brought with him advanced programming skills and links to the corporate world of computing, along with a commitment to empowering schoolchildren. Brand and Raymond both had extensive experience in the Bay area psychedelic scene. And Portola’s various projects kept its members in circulation: teachers, communards, computer programmers – all came through the offices at one time or another.” [Page 70]

An additional note states: “For a fascinating account of the intermingling of countercultural and technological communities in this area see What the Dormouse Said. How the 60s Counterculture shaped the Personal Computer by John Markoff, Viking Penguin 2005.” Turner is convincing in the description of the society turbulence, with the New Left focusing on civil rights whereas the New Communalists in a less organized, more anarchist vision of the world, neither being opposed to technology, but trying to scale down the impact of capitalism and cold war, Norbert Wiener, Marshall McLuhan and Buckminster Fuller being influential thinkers.

Turner concludes his chapters with these quotes : “Once while working with him on the catalog, I asked Mr. Brand if he would not carry out any of a various number of politically oriented underground newspapers. Upon reply, he told me that three of the first restrictions he made for the catalog were no art, no religion, no politics.” … then pointed out that Catalog offered all three : the art was fined art or craft; the religion, Eastern; the politics; libertarian: “From all the 128 pages of the Whole Earth catalog there emerges an unmentioned political viewpoint, the whole feeling of escapism which the catalog conveys is to me unfortunate.”

Brand responded with a defense of local action and of his personal experience : The capitalism question is interesting: I’ve yet to figure out what capitalism is, but if it’s what we’re doing, I dig it. Oppressed peoples: all I know is that I’ve been radicalized by working on the Catalog into far more personal involvement with politics than I had as an artist. My background is pure WASP, wife is American Indian. Work I did a few years ago with Indians convinced me that any guilt-based action toward anyone (personal or institutional) can only make a situation worse. Furthermore the arrogance of Mr. Advantage telling Mr. Disadvantage what to do with his life is sufficient case for rage. I ain’t black, nor poor nor very native to anyplace, not eager any longer to pretend that I am – such identification is good education, but not particularly a good position for being useful to others. I am interested in the Catalog format being used for all manners of markets – a black catalog, a Third World one, whatever, but to succeed I believe it must be done vy people who live there, not well-meaning outsiders. I’m for power to the people and responsibility to the people: responsibility is individual stuff. [Page 99]

And a little further a tough comment by Turner : Like P. T. Barnum, he had gathered the performers of his day – the commune dwellers, the artists, the researchers, the dome builders – into a single circus. And he himself had become both master and emblem of its many linked rings. [Page 101]

Taking the Whole Earth Digital

The next chapters covers the influence of the Whole Earth Catalog, outside the more or less closed circles of the famous Augmented Research Center (ARC) of Douglas Engelbart at the Stanford Research Institute (SRI) and the Palo Also Reserach Center (PARC) of Xerox, undoubtedly materialized in the no less famous Homebrew Computer Club. The cross-influences are multiple and described in detail by Fred Turner, in his chapter Taking the Whole Earth Digital.

There is in particular the reference to an article that I did not know from Rolling Stone magazine written by Steward Brand with photographs by Annie Lebowitz: Spacewar: Fanatic Life and Symbolic Death among the Computer Bums.

1972-12-07 Rolling Stone (Excerpt) Spacewar Article V02 - lowresTurner concludes his pages on the Rolling Stone article with this: In the pages of Rolling Stone, the local work of individual programmers and engineers became part of a global struggle for the transformation of the individual and the community. Here, as in the Whole Earth Catalog, small-scale information technologies promised to undermine bureaucracies and bring about both a more whole individual and a more flexible, playful social world. Even before minicomputers had become widely available, Steward brand had helped both their designers and their future users imagine them as “personal technologies”. [Page 118]

In the article, there is a mention of Hackers which ethics are described by Steven Levy, in his book Hackers, Heroes of the Computer Revolution (my next read ?). They include:

– All information should be free.

– Mistrust authority—promote decentralization.

Brand, not surprisingly, celebrates them : I think hackers… are the most interesting and body of intellectuals since the framers of the US constitution. No other group that I know of has set out to liberate a technology and succeeded. They nt only did so against the active disinterest of corporate America, their success forced corporate America to adopt their style in te end. In reorganizing the Information Age around the individual, via personal computers, the hackers may well have saved the Amerian economy. High tech is now something that mass consumers fo, rather than just have done to them… The quietest of the ’60s subcultures has emerged as the most innovative and most powerful – and most suspicious of power. [Page 138]

Turner does not hesitate to nuance Brand’s enthusiasm in the following lines, because once again the arrival of technology in everyday life has been a complex phenomenon in Silicon Valley. I am not even half way through Turner’s book. Maybe another post. Already a very intersting reading.