I mentioned in a recent post – Birth and Death of Silicon Valley ? – the book Making Silicon Valley – Innovation and the Growth of High Tech, 1930-1970 by Christophe Lécuyer.

I had bought that book many years ago and had only read some parts of it. Because Olivier Alexandre (see my posts about his excellent book La Tech) had mentioned it as an excellent work, I finally read it. It is indeed excellent even if demanding and technical.

What is really interesting is what is not well-known about Silicon Valley:

- there was technical activity in Silicon Valley before Fairchild. I always date the birth of Silicon Valley with the foundation of the first semiconductor startup in 1957. Lécuyer tells the history of lesser-known companies such as Litton Engineering Labs, Eimac (Eitel-McCullaugh) and Varian Associates. Strangely enough Lécuyer does not study Hewlett-Packard, probably because that company, founded in 1939, is really well-known. (Lécuyer is a historian and he focuses on publishing new knowledge);

- most of that activity was linked to military activity, first telecommunications then guiding systems and radars. However Silicon Valley really grew when all these companies had to diversify with civilian applications in the early 60s;

- there were as many social innovations as technical ones: in parallel to the development of klystrons, magnetrons, power tubes first and then transistors, planar transistors (“planar process, arguably the most important innovation in the twentieth-century technology” [page 297]), integrated circuits, there were a variety of management experiments, usually not hierarchic and quite egalitarian in decision making, freedom of communication to make the companies more efficient, and related to this there were financial incentives for employees (participation to profits, stock options);

- Silicon Valley began to develop overseas very early: in 1965 already Fairchild had factories in Hong Kong and South Korea. The rationals were cost cutting and also fear of trade unions. The social innovations mentioned in the previous point were also linked to the fear of powerful trade unions…

- as soon as 1961, Fairchild could not develop all the inventions made in-house. And in some case did not believe in their potential as Gordon Moore himself acknowledged about integrated circuits. Some of the Fairchild employees, including founders, decided to leave to explore these opportunities, sometimes also because they were not happy to be fully recognized and financially rewarded. The first startups were Rheem, Amelco and Signetics;

- the previous point illustrates the difficulty of marketing (see my recent glossary): validating a market with only customers who do not see the value of a product is insufficient. You also have to be able to imagine what customers cannot imagine, such as advances in technology that will eventually make a new generation of products essential, which seem useless or unattractive at the time of analysis…

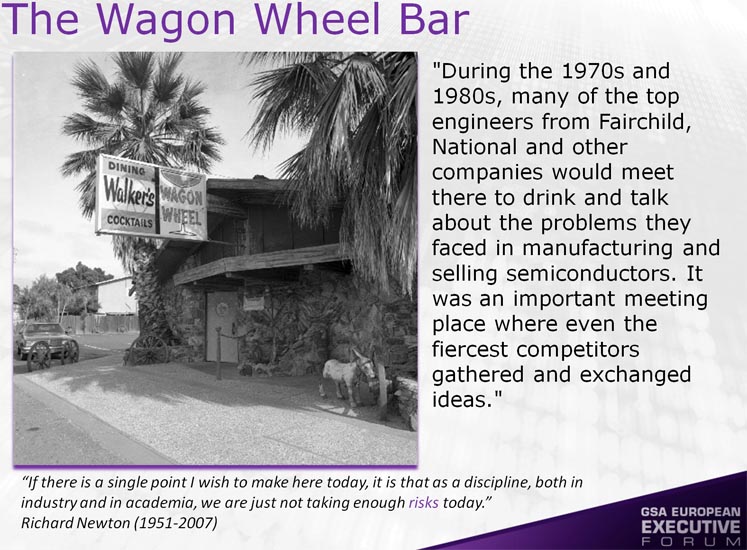

From an anecdotal point of view, Lécuyer mentions the “famous” Wagon Wheel Bar [Page 275]: “Bars also fostered the exchange of information among engineering groups. In the first half of the 1960s, engineers and managers at Fairchild and other Silicon corporations on the Peninsula had developed the habit of meeting after work at a local bar. (The Wagon Wheel Bar as a favorite.) At these bars, they would discuss the problems of teh day. Bars were also wheres sales and marketing men met with the manufacturing guys to discyuss order prices and delivery schedules. After leaving Farichild, many of these engineers returned to these bars and discuss the business with their former associates. A lot of information flowed over beer and hard liquor, to teh point that the management of many of the startups expressly forbid their engineers to go to the Wagon Wheel Bar and other bars. The end result of these daily interactions was that design techniques and solutions to particulary difficult process problems moved from firm to firm. As a result, teh MOS community on the Peninsula developed a repertoire of process “tricks” that were known only in the area. These tricks enabled them to solbve their won process problems and obtain good manufacturing yields. In contrast, MOS firms located outside of Northern Calfornia were not pluged into these networks and did not benefit from this shared knowledge. This put them at a distinct competitive disadvantage.”

In his conclusion, he mentions again the human side : “These men also developed a subculture characterized by its camaraderie, a strong democratic idelology, and genuine appreciation of ingenuity and innovation. […] These groups also brought their professional ideology and politicla ideals. The microwave and silicon communities both valued egalitarianism and viewed engineers as independant professionals. However the microwave and semiconductor communities differed in other ways: a substantial number of the microwave groups had socialist learnings and utopian ideals and longed for a society where the distinction between capital and labor would be abolished. In contrast, the semiconductor community was meritocratic and resolutely capitalistic.” [Page 296]

Lécuyer does not insist too much on individuals, even if he does not neglect the importance people such as Robert Noyce, Gordon Moore and others. He emphasizes more the importance of the collective. He does, however, mention lesser-known characters such as:

- Robert Widlar : “Widlar drank and gave free rein to his irreverent and abnoxious self. Among his many pranks, he once brought a goat to mow national Semiconductor’s lawn. On another occasion, he destroyed the company’s paging system with firecrackers. He also threatened his co-workers with an axe and defied management as much as he could.” [page 269] or

- Pierre Lamond “a tough French engineer that had made a name for himself by overseeing the production of the switching transistor for Control Data” [page 240]. Whatever that means, I can add a personal note because I met Pierre Lamond when he was a venture capitalist at Sequoia and his political positions are more in line with the world of the semiconductor than those of the microwaves!

Lécuyer thus explains a lot of what would come later. He also provides some new elements about why Silicon Valley has been so creative for years, decades, and maybe many to come. The conclusion is a masterpiece of synthesis and I could not avoid scanning it in pdf.

As a reminder:

![]() (High resolution image here).

(High resolution image here).