The debate is recurrent and in my last post, I was questioned about my fascination for start-ups and Silicon Valley. In a way this is related, I will come back on this at the end. Two recent articles nearly surprised me. The first one has a famous author, Clayton Christensen. The Empires Strike Back – How Xerox and other large corporations are harnessing the force of disruptive innovation was published in the latest issue of the MIT Tech Review.

Here are short extracts: “It has been a long time since anyone considered Xerox an innovation powerhouse. On the contrary, Xerox typically serves as a cautionary tale of opportunity lost: many obituaries of Steve Jobs described how his fateful visit to the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center in 1979 inspired many of the breakthroughs that Apple built into its Macintosh computer. Back then, Xerox dominated the photocopier market and was understandably focused on improving and sustaining its high-margin products. The company’s headquarters became the place where inventions in its Silicon Valley lab went to die. Inevitably, simpler and cheaper copiers from Canon and other rivals cut down Xerox in its core market. It is a classic story of the “innovator’s dilemma.” […] But now Xerox is turning things around […] In the past, Xerox’s success would have been an anomaly. Less than a decade ago, when we were finishing the book The Innovator’s Solution we highlighted the fact that disruptive innovations are typically introduced by startups, the rebel forces in the business universe. […] Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, only about 25 percent of disruptive innovations we tracked in our database came from such incumbents, with the rest coming from startups. But during the 2000s, 35 percent of disruptions were launched by incumbents. In other words, the battle seems to be swinging in favor of the Empire, as the following examples confirm. The author mentions examples such as GE, Tesla competing with GM, Dow and Microsoft in the article.

The second article comes from The Ecomist and is entitled “Why large firms are often more inventive than small ones.” Let me quote it a little more extensively: “Joseph Schumpeter […] argued both sides of the case. In 1909 he said that small companies were more inventive. In 1942 he reversed himself. Big firms have more incentive to invest in new products, he decided, because they can sell them to more people and reap greater rewards more quickly. In a competitive market, inventions are quickly imitated, so a small inventor’s investment often fails to pay off. […] These days the second Schumpeter is out of fashion: people assume that little start-ups are creative and big firms are slow and bureaucratic. But that is a gross oversimplification, says Michael Mandel of the Progressive Policy Institute, a think-tank. In a new report on “scale and innovation”, he concludes that today’s economy favours big companies over small ones. Big is back, as this newspaper has argued. And big is clever, for three reasons.” The arguments are that 1-ecosystems are big, 2-markets are globals and 3-problems to be solved on a large scale. This is not for small companies. “He is right that the old “small is innovative” argument is looking dated. Several of the champions of the new economy are firms that were once hailed as plucky little start-ups but have long since grown huge, such as Apple, Google and Facebook. […] Big companies have a big advantage in recruiting today’s most valuable resource: talent. (Graduates have debts, and many prefer the certainty of a salary to the lottery of stock in a start-up.) Large firms are getting better at avoiding bureaucratic stagnation: they are flattening their hierarchies and opening themselves up to ideas from elsewhere. Procter & Gamble, a consumer-goods giant, gets most of its ideas from outside its walls. Sir George Buckley, the boss of 3M, a big firm with a 109-year history of innovation, argues that companies like his can combine the virtues of creativity and scale.”

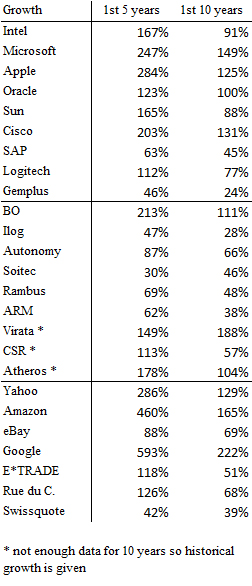

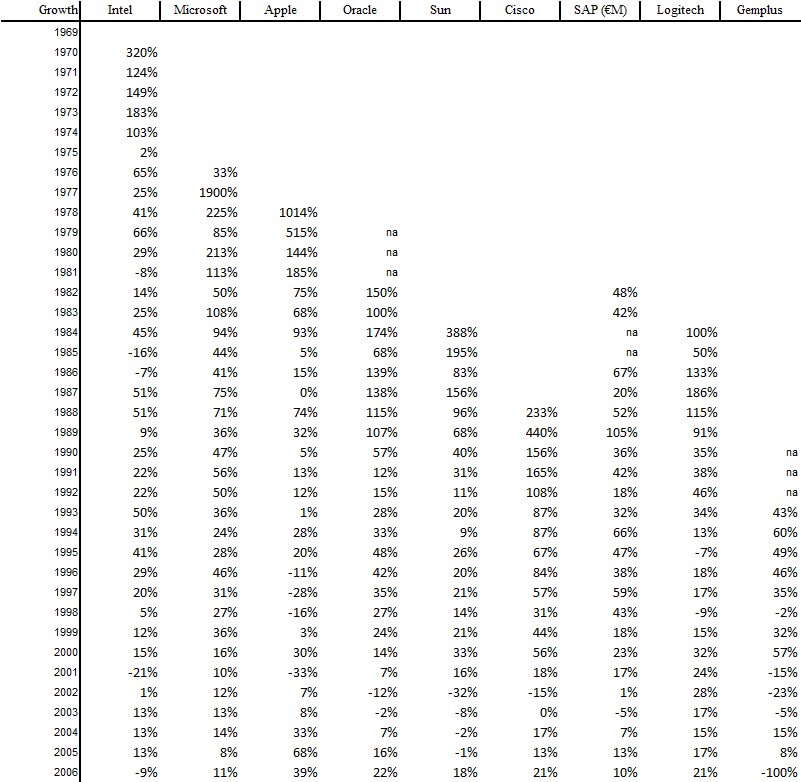

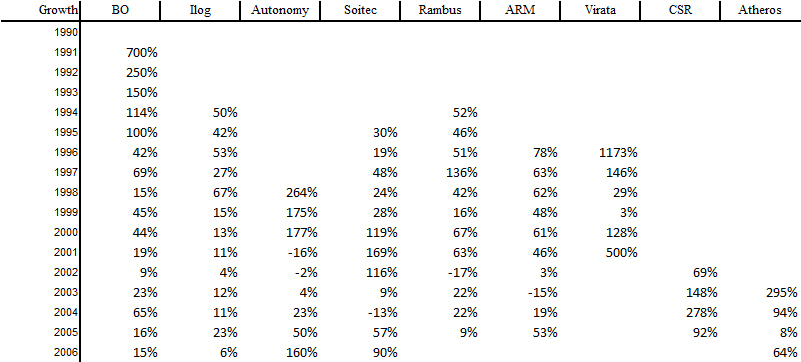

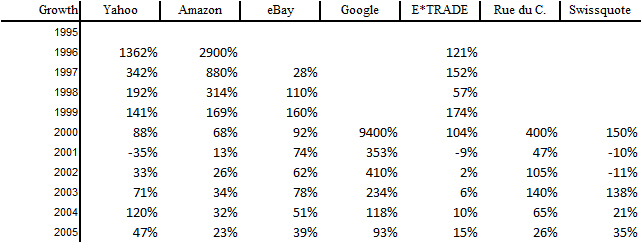

Well I was not surprised for long. The debate is not about small or large. Let me explain by quoting my book again and more specifically the section Small is not Beautiful [page 111] “There is one misunderstanding concerning start-ups. Because they would be young, recent companies, and because many macroeconomic analyses focus on the jobs generated by small structures, there is a tendency to consider with high regard that “small is beautiful” as if it were a motto for start-ups. The ambition of a start-up is not to stay modest. On the contrary, the successful companies have become large, sometimes dinosaurs. In early 2007, Intel had 94’000 employees, Oracle 56’000, Cisco 49’000 and Sun 38’000. These “start-ups” have become multinational companies. […] The San Jose Mercury News, the daily newspaper at the heart of Silicon Valley, publishes once a year for example the list of the 150 biggest companies. The simple comparison of the list between 1997 and 2004 shows that among the top 50 in 2004, 12 were not part of the first 150 in 1997. Zhang also analyzed this astonishing dynamics by comparing the 40 biggest high-tech Silicon Valley companies in 1982 and in 2002 as provided by Dun & Bradstreet. Twenty of the 1982 companies did not exist anymore in 2002 and twenty one of the 2002 companies had not been created in 1982. These dynamics of birth and death are known and positively acknowledged.”

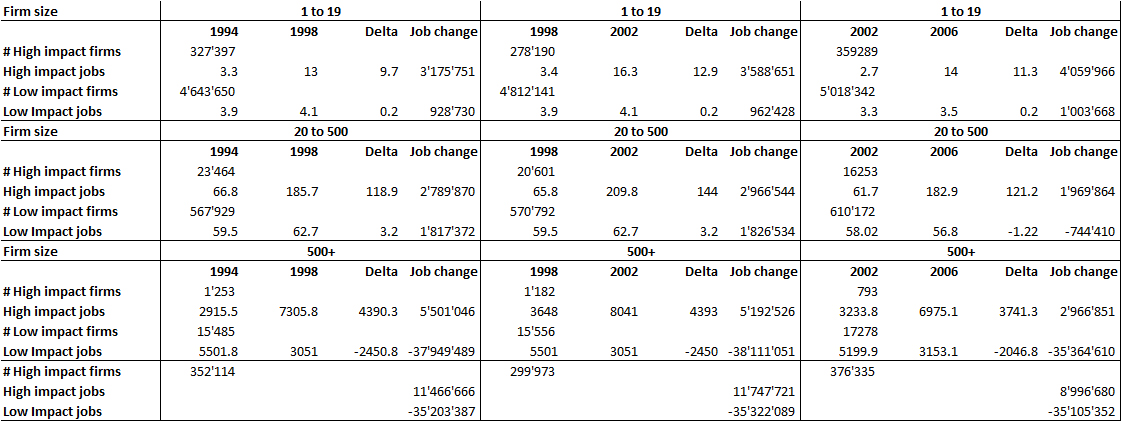

It is exactly what the Economist article explains: “However, there are two objections to Mr Mandel’s argument. The first is that, although big companies often excel at incremental innovation (ie, adding more bells and whistles to existing products), they are less comfortable with disruptive innovation—the kind that changes the rules of the game. The big companies that the original Schumpeter celebrated often buried new ideas that threatened established business lines, as AT&T did with automatic dialling. Mr Mandel says it will take big companies to solve America’s most pressing problems in health care and education. But sometimes the best ideas start small, spread widely and then transform entire systems. Facebook began as a way for students at a single university to keep in touch. Now it has 800m users. The second is that what matters is not so much whether companies are big or small, but whether they grow. Progress tends to come from high-growth companies. The best ones can take a good idea and use it to transform themselves from embryos into giants in a few years, as Amazon and Google have. Such high-growth firms create a lot of jobs: in America just 1% of companies generate roughly 40% of new jobs. Let small firms grow big The key to promoting innovation (and productivity in general) lies in allowing vigorous new companies to grow big, and inefficient old ones to die. On that, Schumpeter never changed his mind.”

I say it again, there is a difference between start-up and SME. This does not fully answer Christensen argument about the Empire striking back. Well it means large companies have smart managers who learnt from the mistakes of the past. But he also implicitely say that 65% of disruptive innovations come from new comers, not incumbents. Gazelles still have a bright future.