(Sorry I was too fast, this should have been posted on the French version… where it is also now. For non French-speaking readers, this post is about new management techniques that were born in Silicon Valley…)

J’étais invité ce matin à débattre des méthodes de travail et de management (y compris “l’utilisation du bonheur”) importées de la Silicon Valley. Je mets plus bas (après les tweets) les notes que j’avais prise pour préparer cette émission

[EN DIRECT] Travail : les nouvelles conditions

Le bonheur, une idée neuve dans les entreprises ?Quelles sont les valeurs portées par le nouveau management ?#management #SiliconValleyhttps://t.co/Kjf7kbTDpZ pic.twitter.com/ngNAvfdYMS

— Culturesmonde (@CulturesMonde_) June 12, 2019

Fabien Blanchot : « Le management ne disparaît pas. En revanche il peut y avoir débat sur l’existence ou non de managers. Même si on supprime les coachs, on fait perdurer des accompagnateurs. #management #manager https://t.co/Kjf7kcbeOz» pic.twitter.com/evCm0B47ah

— Culturesmonde (@CulturesMonde_) June 12, 2019

.@hlebret : « C’est une recherche d’efficacité qui n’est pas manipulatoire, qui a souvent été discutée avec les employés eux-mêmes. »#management #bonheurhttps://t.co/Kjf7kcbeOz pic.twitter.com/fmbbg93rc8

— Culturesmonde (@CulturesMonde_) June 12, 2019

Fabien Blanchot : « Dans l’économie de la connaissance, il faut faire vibrer les cerveaux et les cœurs. On est nécessairement dans un mode de management qui doit tenir compte des aspirations de ces cerveaux et de ces cœurs. » https://t.co/Kjf7kcbeOz pic.twitter.com/o6yGZBHldl

— Culturesmonde (@CulturesMonde_) June 12, 2019

.@jbaptistemalet : « Beaucoup d’employés qui entrent dans un entrepôt Amazon ont des paillettes dans les yeux. Ils déchantent car ils réalisent rapidement qu’il s’agit d’un vernis. »#Amazon #entrepot #managementhttps://t.co/Kjf7kcbeOz pic.twitter.com/iyPwyCTQ6t

— Culturesmonde (@CulturesMonde_) June 12, 2019

.@hlebret « On ne peut malheureusement pas comparer la situation d’un employé dans un entrepôt d’Amazon et celle d’un jeune développeur qui arrive à Google avec un doctorat de Stanford. »#management #Google #Amazonhttps://t.co/Kjf7kcbeOz pic.twitter.com/re8pHUi6ga

— Culturesmonde (@CulturesMonde_) June 12, 2019

Voici les notes que je m’étais préparées.

On ne peut pas mettre dans les même paquet tous les GAFAM. Tout d’abord Amazon et Microsoft qui par coïncidence ne sont pas basées dans la Silicon Valley, mais à Seattle ne sont pas connues pour un management original. Ni Bill Gates, ni son successeur Steve Ballmer, ni Jeff Bezos ne sont connus pour des styles de management innovants. Par contre Google, Apple et Facebook ont sans doute des similarités:

– ce sont des méritocraties et le travail est la valeur “suprême”, plus que le profit, au risque de tous les excès: recherche de performance, concurrence et risque de burn-out. On ne tient pas toujours très longtemps chez GAF

– on y recherche les meilleurs talents (sur toute la planète et sans exclusive, au fond le sexisme et le racisme n’y existent pas a priori)

– le travail en (petites) équipes est privilégié.

Du coup le management a innové pour permettre cette performance et reconnaître les talents (par le fameuses stock options mais aussi une multitude de services pour rendre les gens toujours plus efficaces)

J’aimerais vous mentionner 3 ouvrages (sur lesquels j’avais bloggé pour 2 d’entres eux)

– Work Rules décrit le “people management” chez Google (ils ne parlent “plus” de ressources humaines). L’auteur Lazlo Bock qui fut le patron de cette activité a quasiment théorisé tout cela. Vous trouverez mes 5 posts sur ce livre par le lien: https://www.startup-book.com/fr/?s=bock. C’est un livre en tout point remarquable parce qu’il montre la complexité des choses.

– I’m feeling Lucky décrit de l’intérieur ces manières hétérodoxes de “foncer”. Un pro du marketing montre comment Google a tout chamboulé par conviction / intuition plus que par expérience. https://www.startup-book.com/fr/2012/12/13/im-feeling-lucky-beaucoup-plus-quun-autre-livre-sur-google/

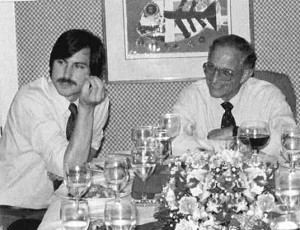

– Enfin un livre hommage sur Bill Campbell vient de sortir écrit par l’ancien CEO de Google Eric Schmidt. https://www.trilliondollarcoach.com. Comme je viens de commencer ce livre, je peux en parler plus difficilement mais il serait dommage d’oublier cette personnalité qui fut le “coach” de Steve Jobs, Eric Schmidt et Sheryl Sandberg, trois personnes majeures pour justement les GAF! Or ce Bill Campbell, décédé il y a 3 ans, fut une personne essentielle à cette culture du travail et de la performance. Ses valeurs sont décrites dans https://www.slideshare.net/ericschmidt/trillion-dollar-coach-book-bill-campbell. Bill Campbell revient de temps en temps sur mon blog pour des anecdotes assez étonnantes. (https://www.startup-book.com/fr/?s=campbell). Par exemple, chez Google on a souvent pensé que les managers étaient inutiles. L’autonomie d’individus brillants devait suffire… mais ce n’est pas si simple! – voir https://www.startup-book.com/fr/2015/09/01/google-dans-le-null-plex-partie-3-une-culture/.

A nouveau excellence des individus et travail en équipe, reconnaissance des talents à qui on donne autonomie, responsabilité(s) avec peu de hiérarchie semble être le leitmotiv… Tout cela on pas pour rendre les gens heureux, mais pour leur permettre d’être plus efficace parce qu’ils sont “heureux” au travail. “People First”. L’objectif c’est de fidéliser, de rendre plus productif, mais c’est aussi une mise en pratique de la confiance en les autres.

Alors comme je l’avais lu chez Bernard Stiegler, à toute pharmacopée sa toxicité. Les excès dans des valeurs conduisent à des abus. Trop de travail, de concurrence, de pression conduit au burnout. J’ai l’impression que la politique et même le sexisme y jouent moins de rôle qu’on pense, même s’il y en a comme partout. Quant au racisme, il me semble limité (et on est aux USA!) Le sexisme est un vrai sujet, mais je vois plus des nerds qui ont peur ou ne connaissent pas les femmes que des “old boy clubs of white men” qui dirigeraient les choses comme je l’ai lu (même si cet élément existe j’en suis sûr). La polémique sur la congélation des ovocytes chez Facebook peut être lue de manière contradictoire j’imagine. J’ai aussi abordé le sujet dans le passé, https://www.startup-book.com/fr/?s=femmes ou https://www.startup-book.com/tag/women-and-high-tech/. L’autre sujet de diversité, est plus clair: il y a tellement de nationalités dans les GAFAs et les startup en général que le racisme est dur à imaginer. Indiens, chinois surtout sont présents et jusqu’au somment (les CEO de Google et Microsoft aujourd’hui). Seule la minorité “African-American” est sans doute sous représentée et on peut imaginer que tout cela est corrélé avec le problème de l’accès à l’éducation (qui existe moins en Asie)

Voilà, c’est déjà beaucoup pour ne pas dire trop… je trouve que commencer par Bill Campbell est une manière simple et efficace d’entrer dans le sujet. Et maintenant que j’y pense tout cela est d’autant plus facilement que vous verrez que mes lectures récentes sont liées au “sens du travail” (Lochmann, Crawford, Patricot) https://www.startup-book.com/fr/?s=travail