I must thank my friend and colleague Fuad for pointing to me a remarkable research article entitled Talent vs Luck: the role of randomness in success and failure. You can find the paper on Arxiv in pdf format.

I must say this resonates with research I did in the past on serial entrepreneurs, where I discovered there was no real correlation between experience and success in high-tech entrepreneurship. Here is a link to this work: Serial entrepreneurs: are they better?

If you are interested, just download and read the paper. Here are some short teasers from their paper:

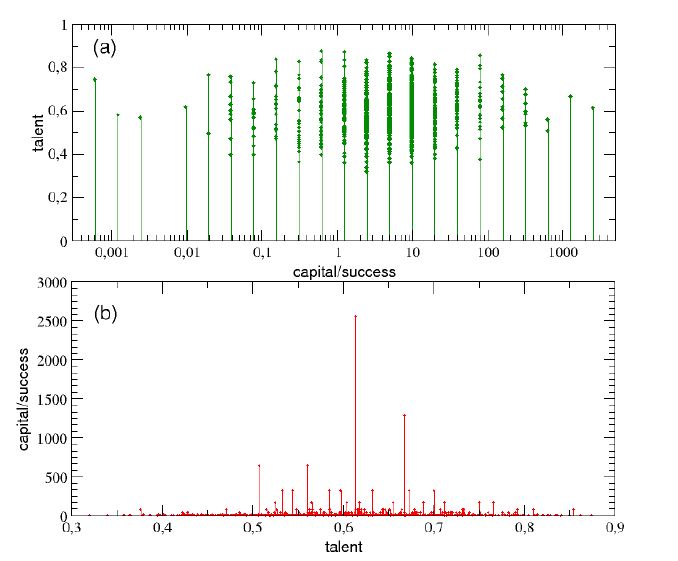

It is very well known that intelligence (or, more in general, talent and personal qualities) exhibits a Gaussian distribution among the population, whereas the distribution of wealth – often considered a proxy of success – follows typically a power law (Pareto law), with a large majority of poor people and a very small number of billionaires. Such a discrepancy between a Normal distribution of inputs, with a typical scale (the average talent or intelligence), and the scale invariant distribution of outputs, suggests that some hidden ingredient is at work behind the scenes. In this paper, with the help of a very simple agent-based toy model, we suggest that such an ingredient is just randomness. [Page 1]

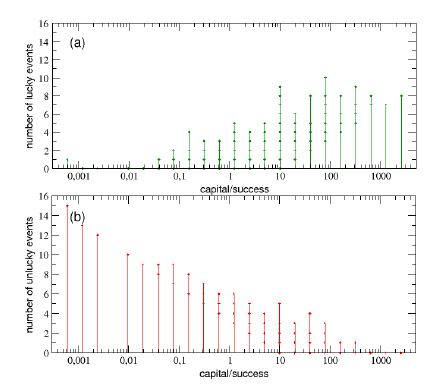

There is nowadays an ever greater evidence about the fundamental role of chance, luck or, more in general, random factors, in determining successes or failures in our personal and professional lives. In particular, it has been shown that scientists have the same chance along their career of publishing their biggest hit; that those with earlier surname initials are significantly more likely to receive tenure at top departments; that the distributions of bibliometric indicators collected by a scholar might be the result of chance and noise related to multiplicative phenomena connected to a publish or perish inflationary mechanism; that one’s position in an alphabetically sorted list may be important in determining access to over-subscribed public services; that middle name initials enhance evaluations of intellectual performance; that people with easy-to-pronounce names are judged more positively than those with difficult-to-pronounce names; that individuals with noble-sounding surnames are found to work more often as managers than as employees; that females with masculine monikers are more successful in legal careers; that roughly half of the variance in incomes across persons worldwide is explained only by their country of residence and by the income distribution within that country; that the probability of becoming a CEO is strongly influenced by your name or by your month of birth; that the innovative ideas are the results of a random walk in our brain network; and that even the probability of developing a cancer, maybe cutting a brilliant career, is mainly due to simple bad luck. Recent studies on lifetime reproductive success further corroborate these statements showing that, if trait variation may influence the fate of populations, luck often governs the lives of individuals. [Page 2]

So here are some striking results:

But to understand the real meaning of [these] findings it is important to distinguish the macro from the micro point of view. In fact, from the micro point of view, following the dynamical rules of the model, a talented individual has a greater a priori probability to reach a high level of success than a moderately gifted one, since she has a greater ability to grasp any opportunity that will come. Of course, luck has to help her in yielding those opportunities. Therefore, from the point of view of a single individual, we should therefore conclude that, being impossible (by definition) to control the occurrence of lucky events, the best strategy to increase the probability of success (at any talent level) is to broaden the personal activity, the production of ideas, the communication with other people, seeking for diversity and mutual enrichment. In other words, to be an open- minded person, ready to be in contact with others, exposes to the highest probability of lucky events (to be exploited by means of the personal talent). On the other hand, from the macro point of view of the entire society, the probability to find moderately gifted individuals at the top levels of success is greater than that of finding there very talented ones, because moderately gifted people are much more numerous and, with the help of luck, have – globally – a statistical advantage to reach a great success, in spite of their lower individual a priori probability. [Page 14]

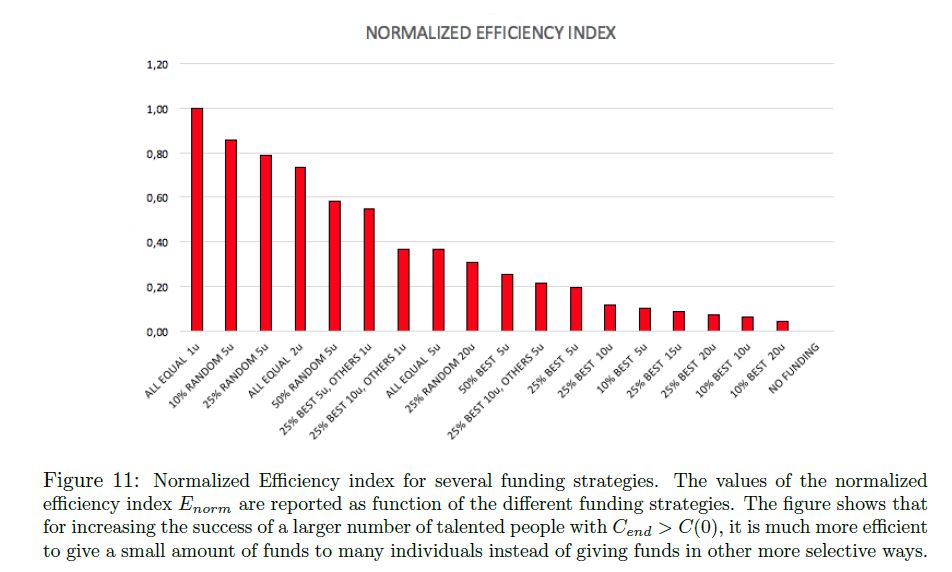

The authors draw some practical recommendations: for example, for strategies about funding research among a diversity of talented people looking at the table [below], it is evident that, if the goal is to reward the most talented persons (thus increasing their final level of success [C]), it is much more convenient to distribute periodically (even small) equal amounts of capital to all individuals rather than to give a greater capital only to a small percentage of them, selected through their level of success – already reached – at the moment of the distribution. The histogram shows that the “egalitarian” criterion, which assigns 1 unit of capital every 5 years to all the individuals is the most effcient way to distribute funds. [Pages 17-18]

Finally, the environment may have a role, such as improbing education, hence talent: Strengthening the training of the most gifted people or increasing the average level of education produce, as one could expect, some beneficial effects on the social system, since both these policies raise the probability, for talented individuals, to grasp the opportunities that luck presents to them. On the other hand, the enhancement in the average percentage of highly talented people who are able to reach a good level of success, seems to be not particularly remarkable in both the cases analyzed, therefore the result of the corresponding educational policies appears mainly restricted to the emergence of isolated extreme successful cases. […] Also, it results that increasing the variance without changing the average, enhances the chances for more talented people to get a very high success. This, on one hand, could be considered positive but, on the other hand, it is an isolated case and it has, as a counterpart, an increase in the gap between unsuccessful and successful people. Increasing the average without changing the variance induces that also in this case the chances for more talented people to get a very high success are enhanced, while the gap between unsuccessful and successful people is lower than before. [Pages 20-21]

As a stimulating conclusion, the authors write: Our results highlight the risks of the paradigm that we call “naive meritocracy”, which fails to give honors and rewards to the most competent people, because it underestimates the role of randomness among the determinants of success. In this respect, several dfferent scenarios have been investigated in order to discuss more effcient strategies, which are able to counterbalance the unpredictable role of luck and give more opportunities and resources to the most talented ones – a purpose that should be the main aim of a truly meritocratic approach. Such strategies have also been shown to be the most beneficial for the entire society, since they tend to increase the diversity of ideas and perspectives in research, thus fostering also innovation. [Page 23]