I have already said here how much I liked Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century (see Has the world gone crazy? Maybe…). In finally ending my reading of the French edition of this 970-page book, I could not help thinking that the author would soon have the Nobel Prize in Economics, even though I have no competence to judge.

When reading his conclusion, I found in the author’s words one of the reasons for my respect regarding this work: “Let us repeat it: the sources gathered in this book are more extensive than those of the previous authors, but they are imperfect and incomplete. All the conclusions I have reached are inherently fragile and deserve to be challenged and debated. Research in social science is not intended to produce ready-made mathematical certainties and to substitute for public, democratic and contradictory debate” [Page 941].

He adds further on: “I see no other place for the economy but as a sub-discipline of the social sciences. […] I do not much like the expression “economic science”, which seems to me to be terribly arrogant and which could lead one to believe that the economy would have reached a higher scientific specificity, distinct from other social sciences. […] One can, for example, spend a great deal of time demonstrating the indisputable existence of a pure and true causality, by forgetting in passing that the question treated is sometimes of limited interest.” [Page 945-7].

Piketty also summarizes his work in a few lines [Page 942]:

“The general lesson of my inquiry is that the dynamic evolution of a market economy and of private property, left to itself, contains within it important convergent forces, linked in particular to the dissemination of knowledge and qualifications, but also powerful forces of divergence, potentially threatening for our democratic societies and the values of social justice on which they are based.

The main destabilizing force is related to the fact that the private rate of return on capital r can be strongly and permanently higher than the growth rate of income and output. The inequality r > g implies that the heritages of the past recapitalize faster than the rate of increase of production and wages. […] The entrepreneur tends inevitably to become an annuitant. […] The past devours the future.”

And the solution is clear: “The right solution is the progressive annual tax on capital. […] The difficulty is that this solution requires a very high degree of international cooperation and regional political integration” [Pages 943-44].

All is said.

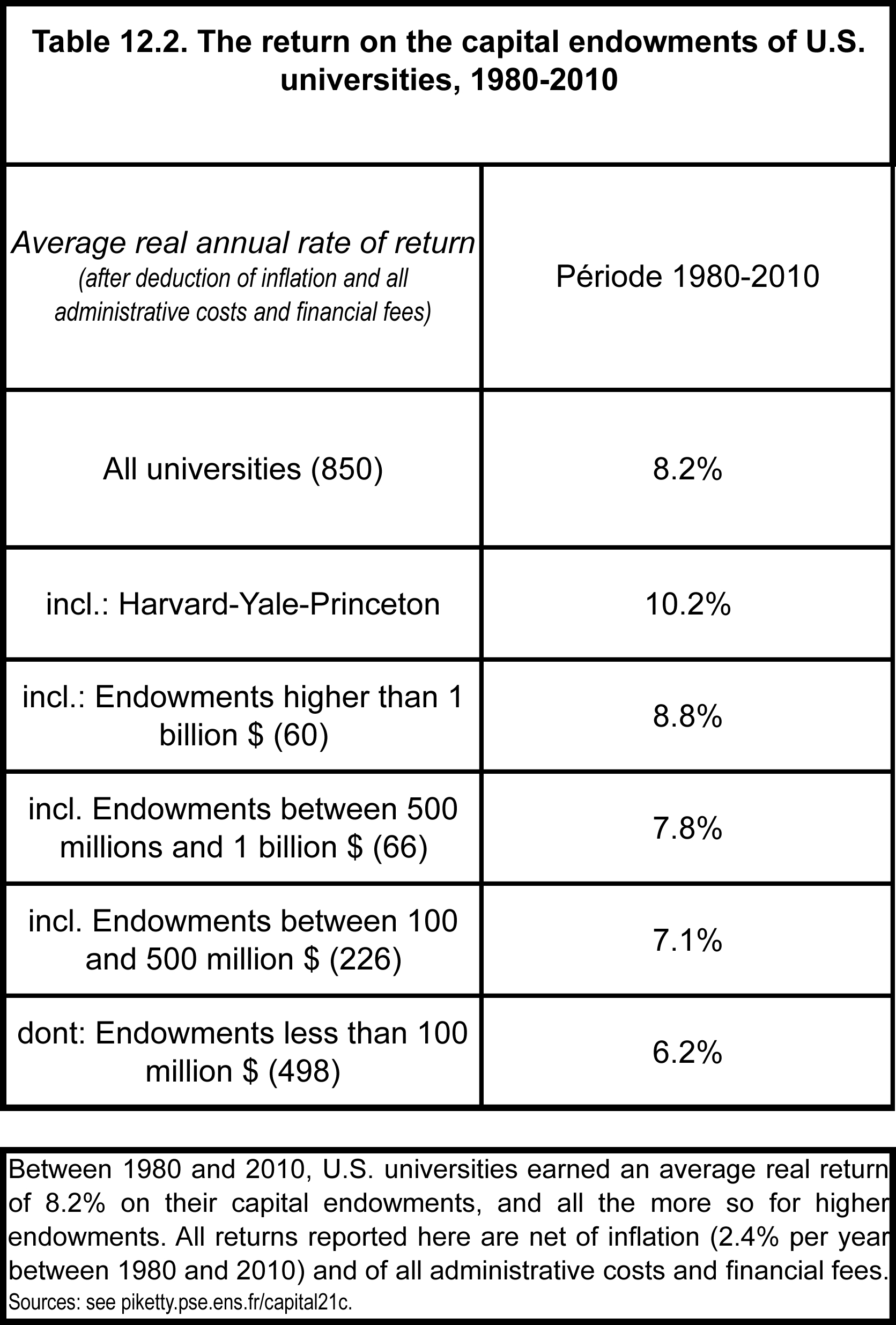

I can not help ending this brief article by recalling a striking example among the multitude of data analyzed: