I am reading a new book on Steve Jobs and Silicon Valley entitled The Apple Revolution. I will come back on what I think when I am finished reading it. I discovered in the first pages of this book that famous author Tom Wolfe had written in 1983 another article about Silicon Valley centered around Bob Noyce, The Tinkerings of Robert Noyce.

You probably do not remember my previous posts mentioning Noyce, and if not you may want to read them:

– What is the mentor role? in August 2010.

– The Man Behind the Microchip in February 2008.

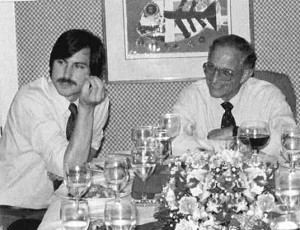

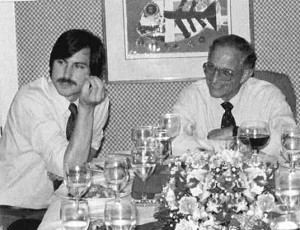

It is not very surprising that Noyce, the founder of Intel, is mentioned in a book about Apple computer. Noyce was a mentor to Jobs as you may see below or by reading my post above. Don Valentine add further that Noyce and Jobs may have been the two most important personalities of Silicon Valley: “There were only two true visionaries in the history of Silicon Valley. Steve Jobs and Bob Noyce. Their vision was to build great companies…”

Wolfe’s article is great and if you do not have time to read The Man behind the Microchip, you might want to read this shorter version. let me just extract a few things:

About the culture of Silicon Valley, work, openness and …

“The new breed of the Silicon Valley lived for work. They were disciplined to the point of back spasms. They worked long hours and kept working on weekends. They became absorbed in their companies the way men once had in the palmy days of the automobile industry. In the Silicon Valley a young engineer would go to work at eight in the morning, work right through lunch, leave the plant at six-thirty or seven, drive home, play with the baby for half an hour, have dinner with his wife, get in bed with her, give her a quick toss, then get up and leave her there in the dark and work at his desk for two or three hours on “a couple things I had to bring home with me.

Or else he would leave the plant and decide, well, maybe he would drop in at the Wagon Wheel for a drink before he went home. Every year there was some place, the Wagon Wheel, Chez Yvonne, Rickey’s, the Roundhouse, where members of this esoteric fraternity, the young men and women of the semiconductor industry, would head after work to have a drink and gossip and brag and trade war stories about phase jitters, phantom circuits, bubble memories, pulse trains, bounceless contacts, burst modes, leapfrog tests, p-n junctions, sleeping-sickness modes, slow-death episodes, RAMs, NAKs, MOSes, PCMs, PROMs, PROM blowers, PROM burners, PROM blasters, and teramagnitudes, meaning multiples of a million millions. So then he wouldn’t get home until nine, and the baby was asleep, and dinner was cold, and the wife was frosted off, and he would stand there and cup his hands as if making an imaginary snowball and try to explain to her… while his mind trailed off to other matters, LSIs, VLSIs, alpha flux, de-rezzing, forward biases, parasitic signals, and that terasexy little cookie from Signetics he had met at the Wagon Wheel, who understood such things.

It was not a great way of life for marriages.”

About youth and innovation:

“The rest of the hotshots were younger. It was a business dominated by people in their twenties and thirties. In the Silicon Valley there was a phenomenon known as burnout. After five or ten years of obsessive racing for the semiconductor high stakes, five or ten years of lab work, work lunches, workaholic drinks at the Wagon Wheel, and work-battering of the wife and children, an engineer would reach his middle thirties and wake up one day; and he was finished. The game was over. It was called burnout, suggesting mental and physical exhaustion brought about by overwork. But Noyce was convinced it was something else entirely. It was…age, or age and status. In the semiconductor business, research engineering was like pitching in baseball; it was 60 percent of the game. Semiconductor research was one of those highly mathematical sciences, such as microbiology, in which, for reasons one could only guess at, the great flashes, the critical moments of inspiration, came mainly to those who were young, often to men in their twenties. The thirty-five year-old burnouts weren’t suffering from exhaustion, as Noyce saw it. They were being overwhelmed, outperformed, by the younger talent coming up behind them. It wasn’t the central nervous system that was collapsing, it was the ego.”

About status, hierarchy and success:

“And if he was extremely bright, if he seemed to have the quality known as genius, he was infinitely more likely to go into engineering in Iowa, or Illinois or Wisconsin, then anywhere in the East. Back east engineering was an unfashionable field. The east looked to Europe in matters of intellectual fashion, and in Europe the ancient aristocratic bias against manual labor lived on. Engineering was looked upon as nothing more than manual labor raised to the level of a science. There was “pure” science and there was engineering, which was merely practical. Back east engineers ranked, socially, below lawyers; doctors; army colonels; Navy captains; English, history, biology, chemistry, and physics professors; and business executives. This piece of European snobbery that said a scientist was lowering himself by going into commerce. Dissenting Protestants looked upon themselves as secular saints, men and women of God who did God’s work not as penurious monks and nuns but as successful workers in the everyday world.”

Although he was an atheist, Wolfe sees in the values of “Dissenting Protestantism” roots of the Silicon Valley culture. “Just why was it that small-town boys from the Middle West dominated the engineering frontiers? Noyce concluded it was because in a small town you became a technician, a tinker, an engineer, and an and inventor, by necessity. “In a small town,” Noyce liked to say, “when something breaks down, you don’t wait around for a new part, because it’s not coming. You make it yourself.”

Interestingly enough the Apple Revolution also mentions all these points, but in the context of the hippie counter-culture… wait for next post!