“Thought is only a flash in the middle of a long night. But this flash means everything.”

Henri Poincaré*

When I talked to friends and colleagues about The Black Swan (“BS”), they were surprised about my interest in the movie with Natalie Portman. I cannot say, I have not watched it. I was talking about Nassem Nicholas Taleb’s book and theory. Some other friends classified at it as American b… s…, these superficial books that give advice on anything and that seem to always become bestsellers; my colleagues would classify it as airport literature, not to be read in academic circles.

I read it and enjoyed it, but I have to admit Taleb is sometimes painful. Is it because he was so much frustrated by I do not know whom or what or is it because he is so proud of his certainties? I am not sure. But his ideas are certainly worth thinking about more than a minute. (Whereas you forget about airport American b… s… after 30 seconds). So back to the BS.

You’ll find great accounts of his book or of his theory, e.g.

– Nassim Taleb’s “The Black Swan” by Andrew Gelman,

– The Wikipedia page on the Black Swan theory

– or even another essay by Taleb, the Fourth Quadrant,

so I will not try to do the same.

However defining the Black Swan might be useful! In the Fourth Quadrant, Taleb writes the following:

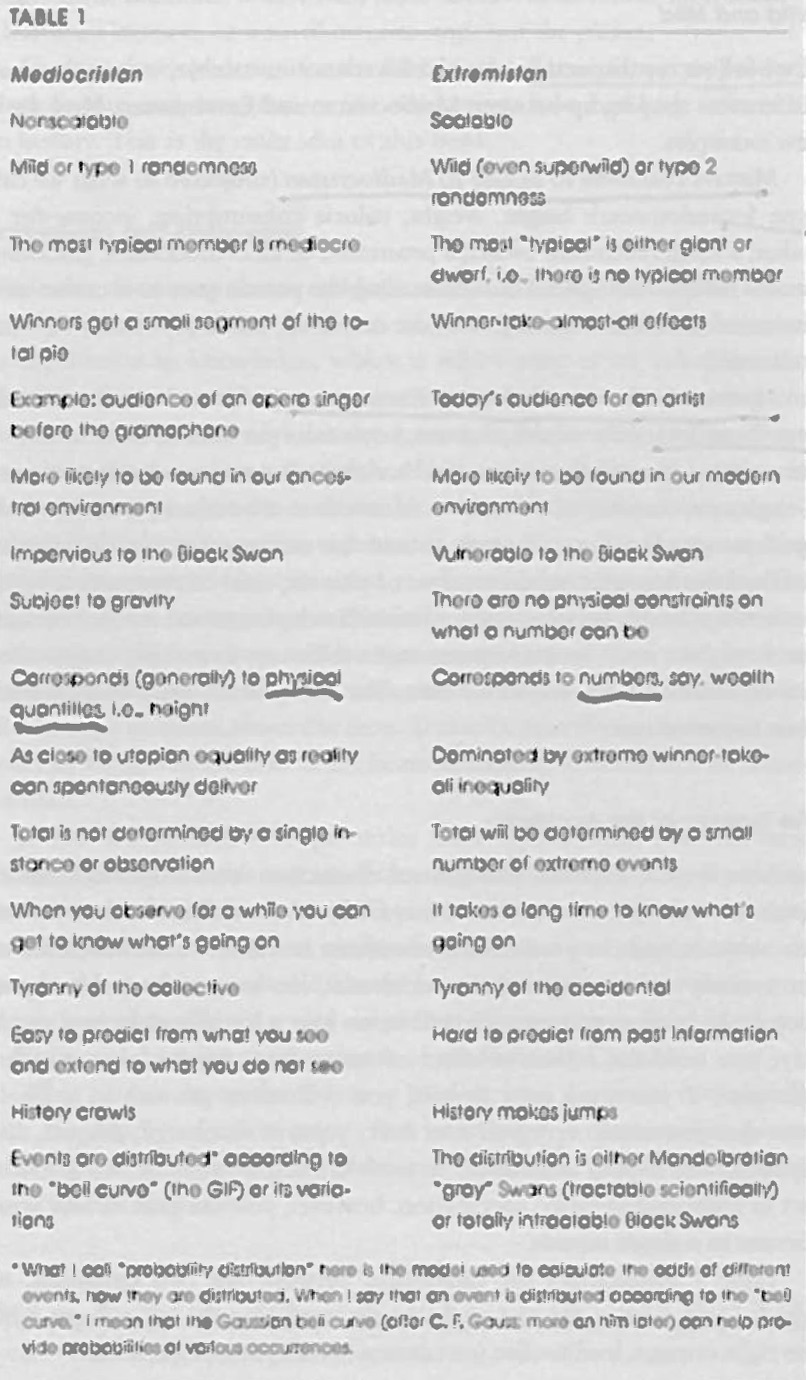

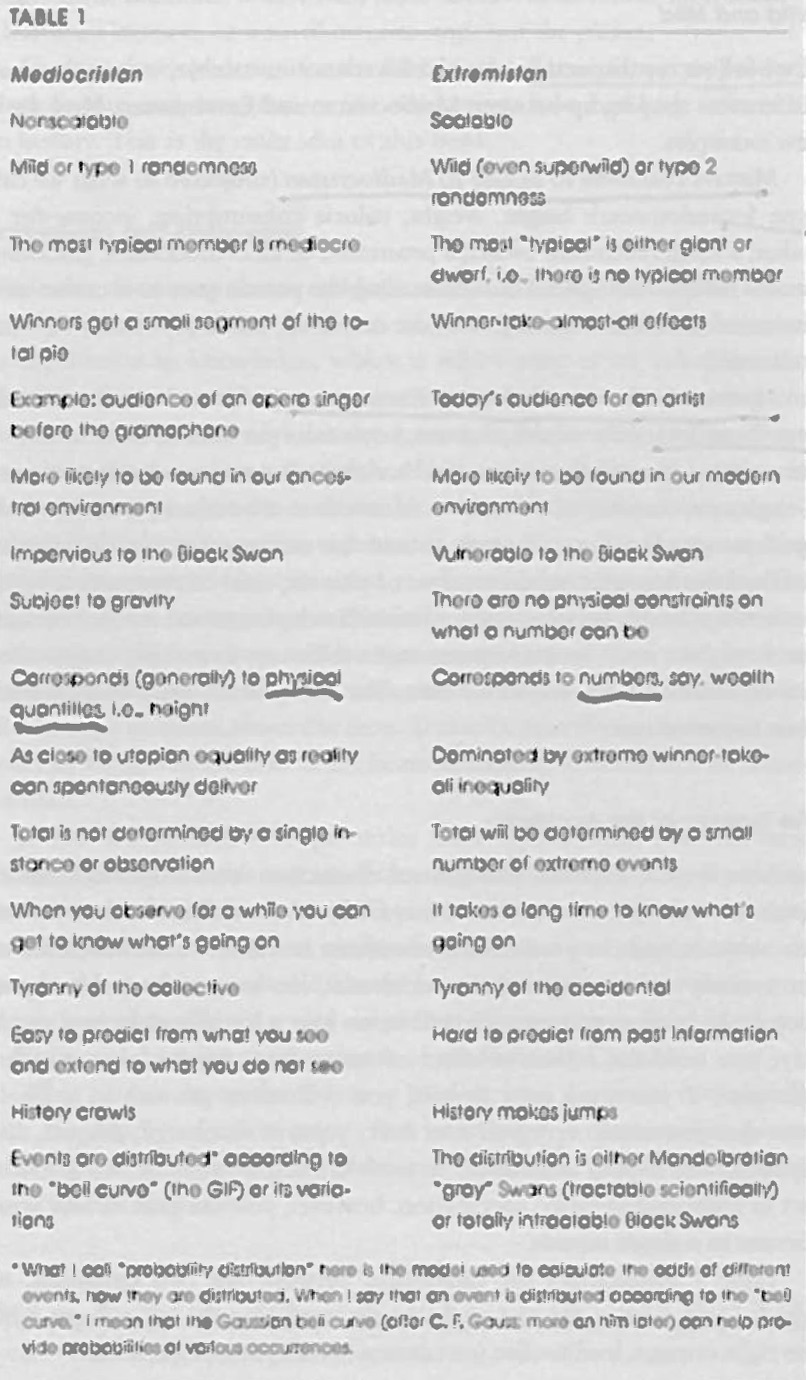

There are two classes of probability domains—very distinct qualitatively and quantitatively. The first, thin-tailed: Mediocristan”, the second, thick tailed Extremistan. Before I get into the details, take the literary distinction as follows: In Mediocristan, exceptions occur but don’t carry large consequences. Add the heaviest person on the planet to a sample of 1000. The total weight would barely change. In Extremistan, exceptions can be everything (they will eventually, in time, represent everything). Add Bill Gates to your sample: the wealth will jump by a factor of >100,000. So, in Mediocristan, large deviations occur but they are not consequential—unlike Extremistan. Mediocristan corresponds to “random walk” style randomness that you tend to find in regular textbooks (and in popular books on randomness). Extremistan corresponds to a “random jump” one. The first kind I can call “Gaussian-Poisson”, the second “fractal” or Mandelbrotian (after the works of the great Benoit Mandelbrot linking it to the geometry of nature). But note here an epistemological question: there is a category of “I don’t know” that I also bundle in Extremistan for the sake of decision making—simply because I don’t know much about the probabilistic structure or the role of large events. Black Swans are the unknown deviations in Extremistan.

Here are more notes taken while reading.

[Page xxii] The black swan is characterized by “rarity, extreme impact and retrospective (though not prospective) predictability” (with additional footnote: the occurrence of a highly improbably event is the equivalent of the nonoccurrence of a highly probably one.

[Page 8] The human mind suffers from 3 aliments:

-The illusions of understanding, or how everyone thinks he knows what is going on in a world that is more complicated (or random) than they realize;

-the retrospective distortion, or how we can assess matters only after the fact, as if they were in a rearview mirror; and

-the overvaluation of factual information and the handicap of authoritative and learned people – when they platonify.

[Page 15] While in the past a distinction had been between drawn Mediterranean and non- Mediterranean (i.e., between the olive oil and the butter), in the 1970s, the distinction suddenly became between Europe and non-Europe.

[Page 54] There is a major difference and often-made mistake between no evidence of something and the evidence of its non-occurence (mental bias.)

[Page 77] The answer is that there are two varieties of rare events: a) the narrated Black Swans, those that are present in the current discourse and that you are likely to hear about on television, and b) those nobody talks about, since they escape models – those that you would feel ashamed discussing in public because they do not seem plausible. I can safely say that it is entirely compatible with human nature that the incidences of Black Swans would be overestimated in the first case, but severely underestimated in the second one.

[Page 80] One death is a tragedy; a million is a statistic. […] We have two systems of thinking. System 1 is experiential, effortless, automatic, fast, and opaque. System 2 is thinking, reasoned, local, slow, serial, progressive. Most mistakes come from using system 1 when we think we use system 2.

[Page 140] We overestimate what we know and underestimate uncertainty. Another bias, ”think about how many people divorce. Almost all of them are acquainted with the statistic that between one-third and one-half of all marriages fail, something the parties involved did not forecast while tying the know. Of course, “not us” because “we get along so well” (as if others tying the know got along poorly.)”

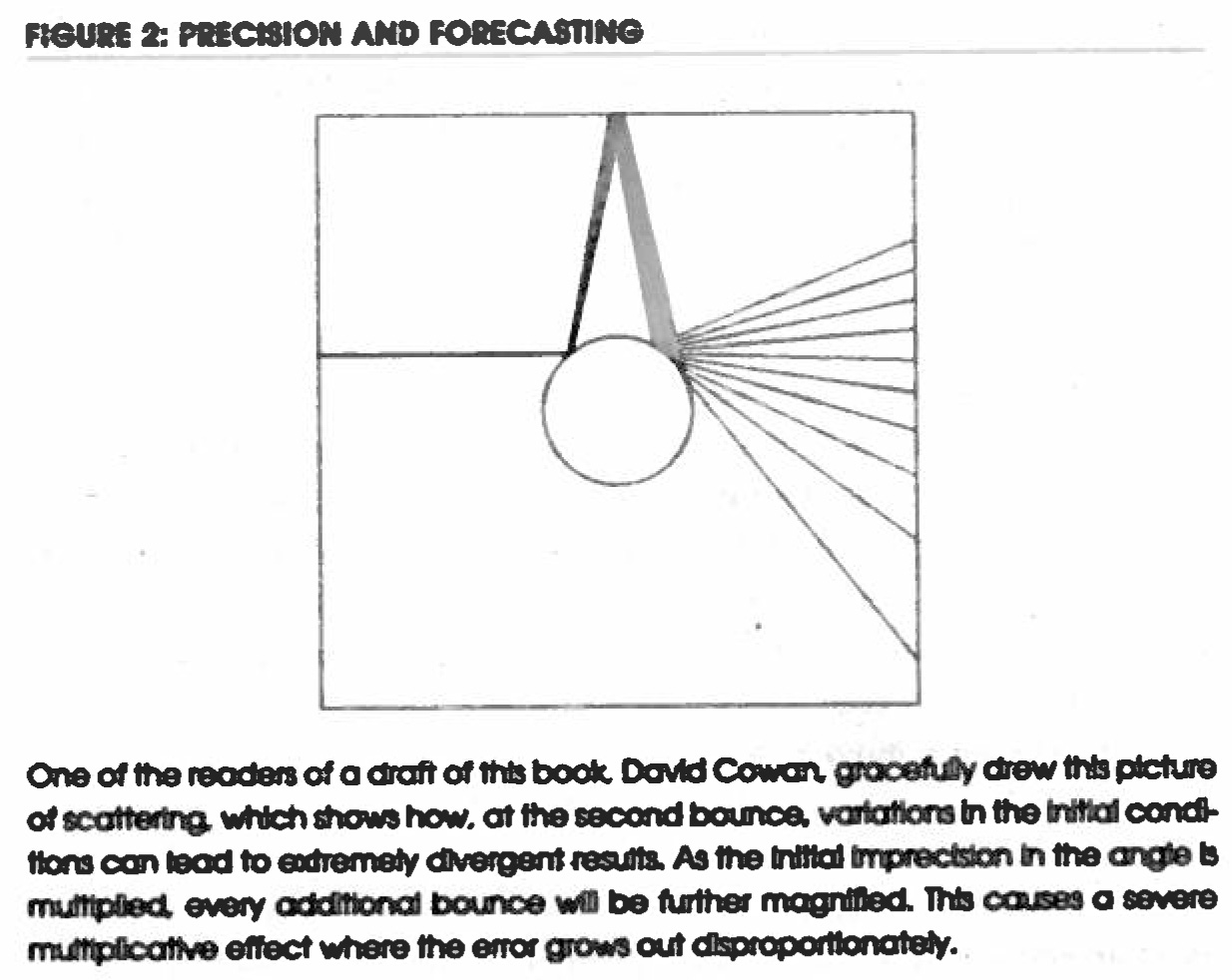

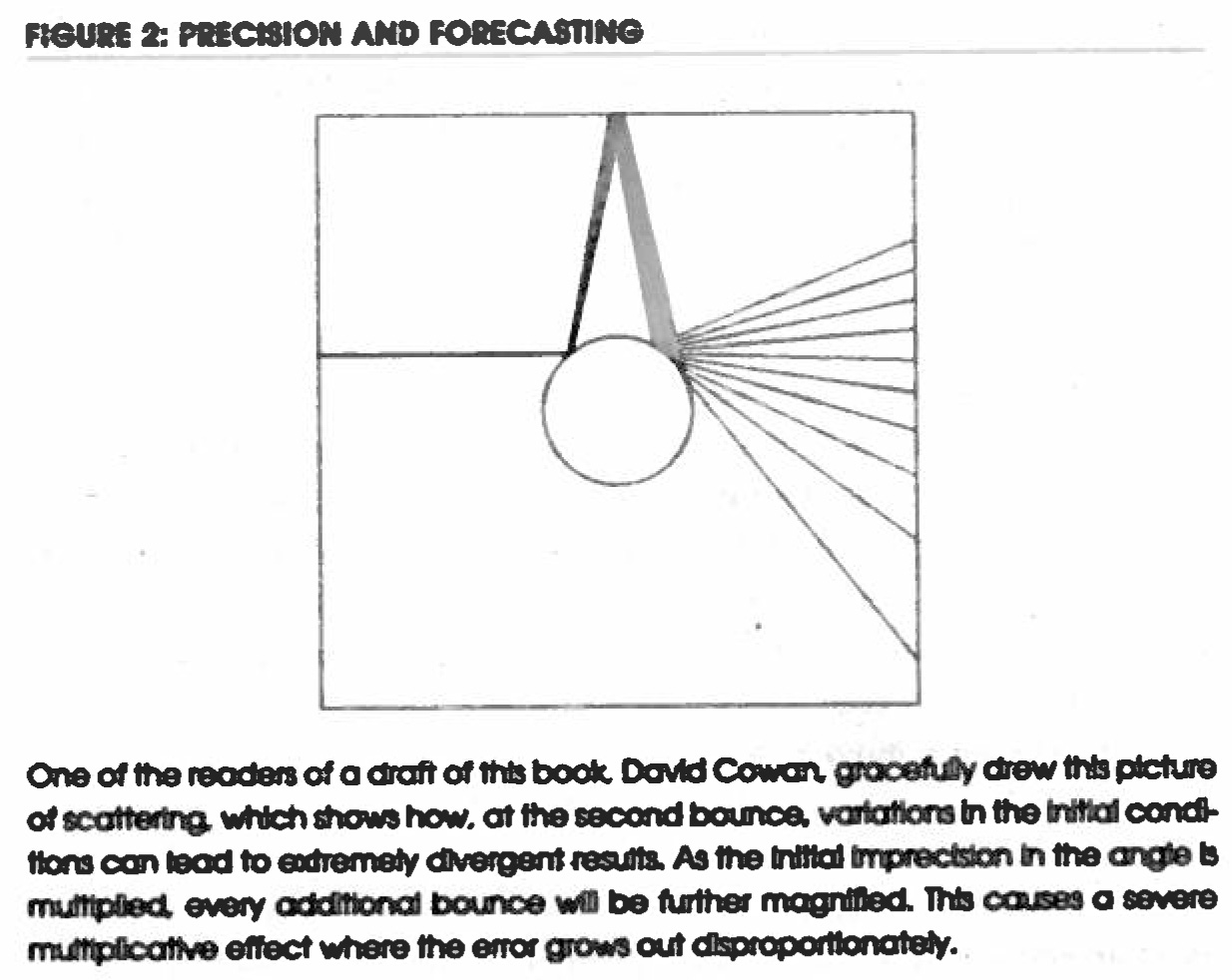

[Page 174-179] Poincaré is a central personality of Taleb’s theory, in particular through the 3-body problem. According to Taleb, “Poincaré angrily disparages the use of the bell curve.” Now the next figure simply illustrates the concept of sensitivity to initial conditions.

Predicting

Operation 1: imagine an ice cube and consider how it may melt.

Operation 2: consider a puddle of water. Try to reconstruct the shape of the ice-cube.

The forward process is generally used in physics and engineering, the backward process in nonrepeatable, nonexperimental historical approaches. And the backward is much more complex to analyze.

[Page 198] While in theory it is an intrinsic property. In practice, randomness is incomplete information. Nonpractitioners do not understand the subtlety. A true random process does not have predictable properties. A chaotic system has entirely predictable properties, but they are hard to know.

a) There are no functional differences in practice between the two since we will never get to make the distinction.

b) The mere fact that a person is talking about the difference implies he has never made a meaningful decision under uncertainty – which is why he does not realize that they are indistinguishable in practice.

Randomness in practice, in the end, is just unknowledge. The world is opaque and appearances fool us.

[Page 204] Trial and error means trying a lot. In the Blind Watchmaker, Richard Dawkins brilliantly illustrates this notion of the world without grand design, moving by small incremental random changes. Note a slight disagreement on my part that does not change the story by much: the world, rather moves by large incremental random changes. Indeed, we have psychological and intellectual difficulties with trial and error and with accepting that series of small failures are necessary in life. “You need to love to lose”. In fact the reason I felt immediately at home in America is precisely because American culture encourages the process of failure, unlike the cultures of Europe and Asia where failure is met with stigma and embarrassment.

[It’s really Taleb writing and not the blog’s author, but I fully agree !]

[Page 207] When you have a very limited loss, you need to be as aggressive as speculative and sometimes as unreasonable as you can be. Middlebrow thinkers sometimes make the analogy with lottery tickets. It is plain wrong. First lottery tickets do not have a scalable payoff. Second, lottery tickets have known rules.

The economics of superstars

[Page 24] Who is this book written for? You need to understand who your audience is and amateurs write for themselves, professionals write for others. [This irony of the author’s is stimulating. I experienced it, I’m an amateur. But are the masterpieces not then written by amateurs? The Black Swans (The Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter) look often like a work of amateurs. The Yevgenia Krasnova example provided by Taleb is also stimulating]

[Page 214] Someone who is marginally better can easily win the entire pot. The problem is the notion of “better.” People take from the poor to give to the rich. An initial advantage follows someone through life and keep getting cumulative advantages. Failure is also cumulative. The advent of modern media has accelerated these cumulative advantages. The sociologist Pierre Bourdieu noted a link between the increased concentration of success and the globalization of culture and economic life.

[Page 221] Taleb claims new comers mitigate the cumulative advantages. “of the five hundred largest US companies in 1957, only seventy-four were still part of that select group, the S&P 500, forty year later. Only a few hundred had disappeared in mergers; the rest either shrank or went bust.

Actors who win an Oscar tend to live on average five years longer than their peers who don’t. People live longer in societies that have flatter social gradients.

[Page 277] What is poorly understood is the absence of a role for the average in intellectual production. The disproportionate share of the very few in intellectual influence is even more unsettling than the unequal distribution of wealth- unsettling because, unlike the income gap, no social policy can eliminate it. Communism could conceal or compress income discrepancies, but it could not eliminate the superstar system in intellectual life. [I am not sure]

Skepticism

Taleb defines himself as a skeptic and his mentor are Hayek and Popper. He links it with humility in the following: [Page 190] Someone with a low degree of epistemic arrogance is not too visible, like a shy person at a cocktail party. We are not predisposed to respect humble people, those who try to suspend judgment. Now contemplate epistemic humility. Think of someone heavily introspective, tortured by the awareness of his own ignorance. He lacks the courage of the idiot, yet has the rare gust to say “I don’t know”. He does not mind looking like a fool or, worse, an ignoramus. He hesitates, he will not commit, and he agonizes over the consequences of being wrong. He introspects, introspects, and introspects until he reaches physical and nervous exhaustion.

Experts

[Page 146] We know the difference between know-how and know-what. The Greeks made a distinction between techne and episteme, craft and knowledge. We have experts who tend to be experts: astronomers, pilots, physicists, mathematicians, accountants and experts who tend to be… note experts: stockbrokers, psychologists, councilors… Simply things that move and therefore require knowledge do not usually have experts and are often Black-Swan-prone. The negative effect of prediction is that those who have a big reputation are worse predictors than those who had none.

[Page 166] The classical model of discovery is as follows: you search for what you know (say, a new way to reach India) and find something you didn’t know was there (America). It’s called serendipity. A term coined in a letter by the writer Hugh Walpole who derived it form a fairy tale, “The Three Princes of Serendip” who “were always making discoveries by accident or sagacity, of things they were not in quest of.“ […] Sir Francis Bacon commented that the most important advances are the least predictable ones.

[Page 169] Engineers tend to develop tools for the pleasure of developing tools. Tools lead to unexpected discoveries. So I disagree with Taleb’s definition: A nerd is simply someone who thinks exceedingly inside the box. It may not be contradictory but I prefer the engineer-like one: “I think a nerd is a person who uses the telephone to talk to other people about telephones. And a computer nerd therefore is somebody who uses a computer in order to use a computer. [https://www.startup-book.com/2012/02/03/triumph-of-the-nerds/]

And [Page 170] Pasteur claims “Luck favors the prepared”

[Page 170] On the difficulty of predicting, just look at the failure of the Segway which “it was prophesized, would change the morphology of cities.”

[Page 184] Another example of Taleb’s target: optimization… Optimization consists in finding the mathematically optimal policy that an economic agent could pursue. Optimization is a case of sterile modeling [discussed also in Chpater 17].

Politics

[Page 16] Categorization always produces a reduction in true complexity. Try to explain why those who favor allowing the elimination of a fetus in the mother’s womb also oppose capital punishment. [Which reminds me of André Frossard : “The unfortunate thing is that the left does not believe much in original sin and that the right has not much faith in redemption.”]

[Page 52] “I never meant that the Conservatives are generally stupid. I meant to say that stupid people are generally conservative” John Stuart Mill once complained. The problem is chronic: if you tell people that the key to success is not always skills, they think that you are telling them that it is never skills always luck.”

[Page 227] Which may explain “we live in a society of one person, one vote, where progressive taxes have been enacted precisely to weaken the winners”. I am not sure if Taleb does not prefer the aristocratic world. At least he seems to favor his friends from that world.

[Page 255] True, intellectually sophisticated characters were exactly what I looked for in life. My erudite and polymathic father – who, were he still alive, would have only been two weeks older than Benoît Mandelbrot [his mentor on non-linear fractals] – liked the company of extremely cultured Jesuit priests. I remember these Jesuit visitors […] I recall that one has a medical degree and a PhD in physics, yet taught Aramaic to locals in Beirut’s Institute of Eastern Languages. […] This kind of erudition impressed my father far more than scientific assembly-line work. I may have something in my genes dirving me away from bildungsphilisters.

Globalization/Scalability

[Page 28] a scalable profession is good only if you are successful; they are more competitive, produce monstrous inequalities and are far more random. Consider the example of the first music recording, of the alphabet, of the printing press. Today a few take almost everything; the rest, next to nothing [page 30].

[Page 32] In Mediocristan,” when your sample is large, no single instance will significantly change the aggregate or the total”. In Extremistan, Bill Gates in wealth or J. K. Rowling in book selling totally change the average of a crowd. “Almost all social matters are from Extremistan.” [When giving a talk on high-tech serial entrepreneurs at BCERC last month, I was slightly criticized with a “but you are only looking at 2% of the entrepreneurs! And I replied, yes but look at the impact…”]

[Page 85] Intellectual, scientific, and artistic activities belong to the province of Extremistan. I am still looking for a single counter-example, a non-dull activity that belongs to Mediocristan.

[Page 90] You not only see that venture capitalists do better than entrepreneurs, but publishers do better than authors, dealers do better than artists, and science does better than scientists.” (I can add that gold seekers made less money than the people who sold them picks and shovels.)

[Page 102] The consequence of the superstar dynamic is that what we call “literary heritage” or “literary treasures” is a minute proportion of what has been produced cumulatively. Balzac was just the beneficiary of disproportionate luck compared to his peers.

[Page 118] The problem here with the universe and the human race is that we are the surviving Casanovas (who should not have survived and had his life without luck – no destiny].

Statistics

Taleb is not against statistics, but against Gaussian law, averages, etc. [Page 37] “The near-Black Swan are somewhat tractable. These are phenomena commonly known by terms such as scalable, scale-invariant, power laws, Pareto-Zipf laws, Yule’s law, Paretian-stable processes, Levy-stable and fractal laws.”

One thousand and one days or the story of the turkey confirms to me that an individual may not owe to the society that fed them initially!

[Page 239] Standard deviations do not exist outside the Gaussian, or if they do exist, they do not matter and do not explain much. But it gets worse. The Gaussian family (which includes various friends and relatives, such as the Poisson law) are the only class of distributions that the standard deviation (and the average) is sufficient to describe. You need nothing else. The bell curve satisfies the reductionism of the deluded. There are other notions that have little or no significance outside of the Gaussian: correlation and worse, regression. Yet they are deeply ingrained in our methods: it is hard to have a business conversation without hearing the word correlation.

[Page 240] Taleb has nothing against mathematicians, but he refers to Hardy’s views: The “real” mathematics of the “real” mathematicians, the mathematics of Fermat end Euler and Gauss and Abel and Riemann, is almost wholly “useless” (and this is as true of “applied” as of “pure” mathematics).

[Page 252] A critical feature of Gaussian statistics is the inclusion of two assumptions: First central assumption: the flips are independent of one another. The coin has no memory. The fact that you got heads or tails on the previous flip does not change the odds of your getting heads or tails on the next one. You do not become a “better” coin flipper over time. If you introduce memory, or skills in flipping, the entire Gaussian business becomes shaky. (Whereas there is preferential attachment and cumulative advantage in non-Gaussian events.) Second central assumption: no “wild” jump. The step size in the building block of the basic random walk is always known, namely one step. There is no uncertainty as to the size of the step.

[…] I have not for the life of me been able to find anyone around me in the business and statistical world who was intellectually consistent in that he both accepted the Black Swan and rejected the Gaussian and Gaussian tools. Many people accepted my Black Swan idea but could not take its logical conclusion, which is that you cannot use one single measure for randomness called standard deviation (and call it “risk”), you cannot expect a simple answer to characterize uncertainty.

But Taleb goes one step further. [Page 272] “But fractal randomness does not yield precise answer. […] Mandelbrot’s fractals allow us to account for a few Black Swans but not all. […] A gray swan concerns modelable extreme events, a black swan is about unknown unknowns. […] I repeat: Mandelbrot deals with gray swans; I deal with the Black Swan. So Mandelbrot domesticated many of my Black Swans, but not all of them, not completely.

Finance

Taleb shows that the stock crashes are sometimes linked to bad modeling and is particularly critical of the Black-Scholes options. He is very much critical of the stock portfolio theories and related Nobel prizes (Markowitz, Samuelson, Hicks or Debreu, “wrecking the ideas of Keynes”. The story of the LTCM hedge fund is an illustration of Taleb’s points.

Business and technology

[Page xxv] Almost no discovery, no technologies of note came from design and planning – they were just Black swans. […] So I disagree with the followers of Marx and those of Adam Smith: the reason free markets work is because they allow people to be lucky thanks to aggressive trial and error, not by giving rewards or “incentives” for skill.

[Page 17] The business world – inelegant, dull, pompous, greedy, unintellectual, selfish and boring.

[…] What I saw was that in some of the most prestigious business schools in the world, the executives of the most powerful corporations were coming to describe what they did for a living and it was possible that they too did not know what was going on.

[Page 135] When I ask people to name three recently implemented technologies that most impact our world today, they usually propose the computer, the Internet and the laser. All three were unplanned, unpredicted and unappreciated upon their discovery, and remained unappreciated well after their initial use. They were consequential. They were Black Swans.

Against averages

[Page 295] Half of the time I am a hyperskeptic; the other half I hold certainties. […] Half of the time I hate Black Swans, the other half I love them. […] Half of the time I am hyperconservative; the other half I am hyperaggressive”. I could delete the quotes!

I am not fully finished with the Black Swan, I am now reading the 70-page postcript essay which Taleb added to the latest paperback edition. There might be more to say (and read if you followed me until now…)

* Poincaré is quoted in Le Monde on July 7, 2012, by Cedric Villani, who by the way also mentions Black Swans in Dans les entrailles des cygnes noirs