Last October I published a post about the article The Case Against Patents by Michele Boldrin and David K. Levine. I had mentioned at the end that there was also a book, entitled Against Intellectual Monopoly. I am not finished with it yet but it is so strange, powerful and complex that I will talk about it in two parts. More in a few days…

It’s a very strange book (and the authors have been known for their arguments for a few years now) because it gives arguments against intellectual property (“IP”). They are not always easy to follow. This is a book about economics which sometimes, often (but not always) confirms the intuition that there is something wrong about IP. Yes inventors, innovators, creators need to be able to protect their creation against thieves. Does it mean they should be given a monopoly (patents) or a right to prevent copy of their work (copyright)? This is what the authors try to address. You can now read my comments but I strongly advise you to read the book and its complex and fascinating arguments, even if in the end, you disagree with them! As a provocative statement, they finish their 1st chapter with: “This leads us to our final conclusion: intellectual property is an unnecessary evil”. [Page 12]

One of their strongest arguments is the following: “It is often argued that, especially in the biotechnology and software industries, patents are a good thing for small firms. Without patents, it is argued, small firms would lack any bargaining power and could not even try to challenge the larger incumbents. This argument is fallacious for at least two reasons. First, it does not even consider the most obvious counterfactual: How many new firms would enter and innovate if patents did not exist, that is, if the dominant firms did not prevent entry by holding patents on pretty much everything that is reasonably doable? For one small firm finding an empty niche in the patent forest, how many have been kept out by the fact that everything they wanted to use or produce was already patented but not licensed? Second, people arguing that patents are good for small firms do not realize that, because of the patent system, most small firms in these sectors are forced to set themselves up as one-idea companies, aiming only at being purchased by the big incumbent. In other words, the presence of a patent thicket creates an incentive not to compete with the monopolist, but to simply find something valuable to feed it, via a new patent, at the highest possible price, and then get out of the way.” [Page 82]

The following is nearly as strong: “The incentive to share information is especially strong in the early stages of an industry, when innovation is fast and furious. In these early stages, capacity constraints are binding, so cost reductions of competitors do not lower industry price, as the latter is completely determined by the willingness of consumers to pay for a novel and scarce good. The innovator correctly figures that by sharing his innovation he loses nothing, but may benefit from one of his competitors leapfrogging his technology and lowering his own cost. The economic gains from lowering own cost or improving own product, when capacity constraints are binding, are so large that they easily dwarf the gains from monopoly pricing. It is only when an industry is mature, cost-reducing or quality improving innovations are harder to come around, and productive capacity is no longer a constraint on demand that monopoly profits become relevant. In a nutshell, this is why firms in young, creative, and dynamic industries seldom rely on patents and copyrights, while those belonging to stagnant, inefficient, and obsolete industries desperately lobby for all kinds of intellectual property protections.” [Page 153]

You can stop here! Or read additional extracts below. Or as I advised go to the book…

“The crucial fact, though, is that the following causal sequence never took place, either in the US or anywhere in the world. The legislative branch passed a bill saying “patent protection is extended to inventions carried out in the area X”, where X was a yet un-developed area of economic activity. A few months, years, or even decades after the bill was passed, inventions surged in area X, which quickly turned into a new, innovative and booming industry. In fact, patentability always came after the industry had already emerged and matured on its own terms. A somewhat stronger test, which we owe to a doubtful reader of our work, is the following: can anyone mention even one single case of a new industry emerging due to the protection of existing patent laws? We cannot, and the doubtful reader could not either. Strange coincidence, is it not?” [Page 51]

In Italy, pharmaceutical products and processes were not covered by patents until 1978; the same was true in Switzerland for processes until 1954, and for products until 1977. [Page 52]

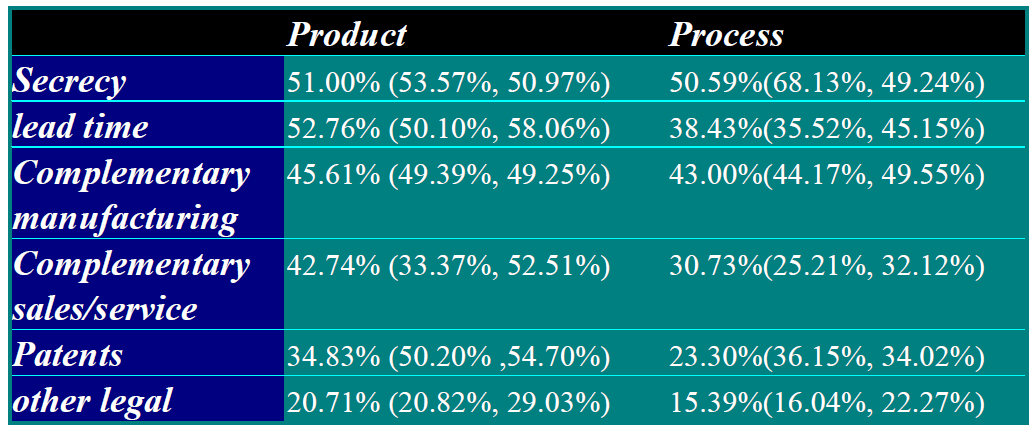

The firms were asked whether particular methods were effective in appropriating the gains from an innovation.The table below shows the percentage of firms indicating that the particular technique was effective. The numbers in parentheses are the corresponding figures for the pharmaceutical and medical equipment industries respectively: these are the two industries in which the highest percentage of respondents indicated that patents are effective. [Page 68]

“While patent pools eliminate the ill effects of patents within the pool – they leave the outsiders, well, outside.” [Page 70]

“Later in the book we talk about the Schumpeterian model of “dynamic efficiency” via “creative destruction.” The latter dreams of a continuous flow of innovation due to new entrants overtaking incumbents and becoming monopolists until new innovators quickly take their place. In this theory, new entrants work like mad to innovate, drawn by the enormous monopoly profits they will make. Our simple observation is that, by the same token, monopolists will also work like mad to retain their enormous monopoly profits. There is one small difference between incumbents and outsiders: the formers are bigger, richer, stronger and way better “connected.” David may have won once in the far past, but Goliath tends to win a lot more frequently these days. Hence, IP-inefficiency.” [Page 76]

“We understand that the careful reader will react to this argument by thinking “Well, the AIDS drugs may be cheap to produce now that they have been invented, but their invention did cost a substantial amount of money that drug companies should recover. If they do not sell at a high enough price, they will make losses, and stop doing research to fight AIDS.” This argument is correct, theoretically, but not so tight as a matter of fact. To avoid deviating from the main line of argument in this chapter we simply acknowledge the theoretical relevance of this counter-argument, and postpone a careful discussion until our penultimate chapter, which is about pharmaceutical research. For the time being, two caveats should suffice. The key word in the former statement is “enough”: how much profits amount to “enough profits?” The second caveat is a bit longer as it is concerned with price discrimination, and we examine it next.” [Page 77] There is a full chapter about Pharam, I will probably cover in part 2 of this article.

Jerry Baker, Senior Vice President of Oracle Corporation: “Our engineers and patent counsel have advised me that it may be virtually impossible to develop a complicated software product today without infringing numerous broad existing patents. … As a defensive strategy, Oracle has expended substantial money and effort to protect itself by selectively applying for patents which will present the best opportunities for cross-licensing between Oracle and other companies who may allege patent infringement. If such a claimant is also a software developer and marketer, we would hope to be able to use our pending patent applications to cross-license and leave our business unchanged.” [Page 80]

Roger Smith of IBM: “The IBM patent portfolio gains us the freedom to do what we need to do through cross-licensing—it gives us access to the inventions of others that are key to rapid innovation. Access is far more valuable to IBM than the fees it receives from its 9,000 active patents. There’s no direct calculation of this value, but it’s many times larger than the fee income, perhaps an order of magnitude larger.”[Page 84]

“Notice, in particular, that patenting is found to be a substitute for R&D, leading to a reduction of innovation. In the authors [Bessen and Hunt]’ calculation, innovative activity in the software industry would have been about 15% higher in the absence of patent protection for new software.” [Page 92]

An example of extreme aberration in U.S. Patent 6,025,810: “The present invention takes a transmission of energy, and instead of sending it through normal time and space, it pokes a small hole into another dimension, thus, sending the energy through a place which allows transmission of energy to exceed the speed of light.” [Page 101]

Arguments in favor of IP are known and quoted again by Levine and Boldrin… “In order to motivate research, successful innovators have to be compensated in some manner. The basic problem is that the creation of a new idea or design … is costly… It would be efficient ex post to make the existing discoveries freely available to all producers, but this practice fails to provide the ex ante incentives for further inventions. A tradeoff arises… between restrictions on the use of existing ideas and the rewards to inventive activity.”[Page 176]

More in part 2….