Nearly 3 years after my unusual post about Obama, here is a post slightly related. Before digging into the topic, I have to admit I have a huge respect for the American president. Even after watching George Clooney’s The Ides of March and the disappointment expressed by many people, I am intrigued and fascinated by his track record. I should add for the anecdote that I was in Washington in October 2009 when he was award the Nobel Peace Prize and in Silicon Valley in September 2011 when he pronounced his recent speech to the Congress. I also quite liked the Titan Dinner.

The White House recently published TAKING ACTION, BUILDING CONFIDENCE and the second initiative is about entrepreneurship. It is worth reading these dense 6 pages and among other things, it is striking to notice that the USA, “the most entrepreneurial nation on earth” [page 17] is extremely worried about an “increasingly unfavorable environment” and a “fallen optimism”. For these reasons, the report suggests 12 initiatives to “help spur renewed entrepreneurship”. (They are listed at the bottow on this post)

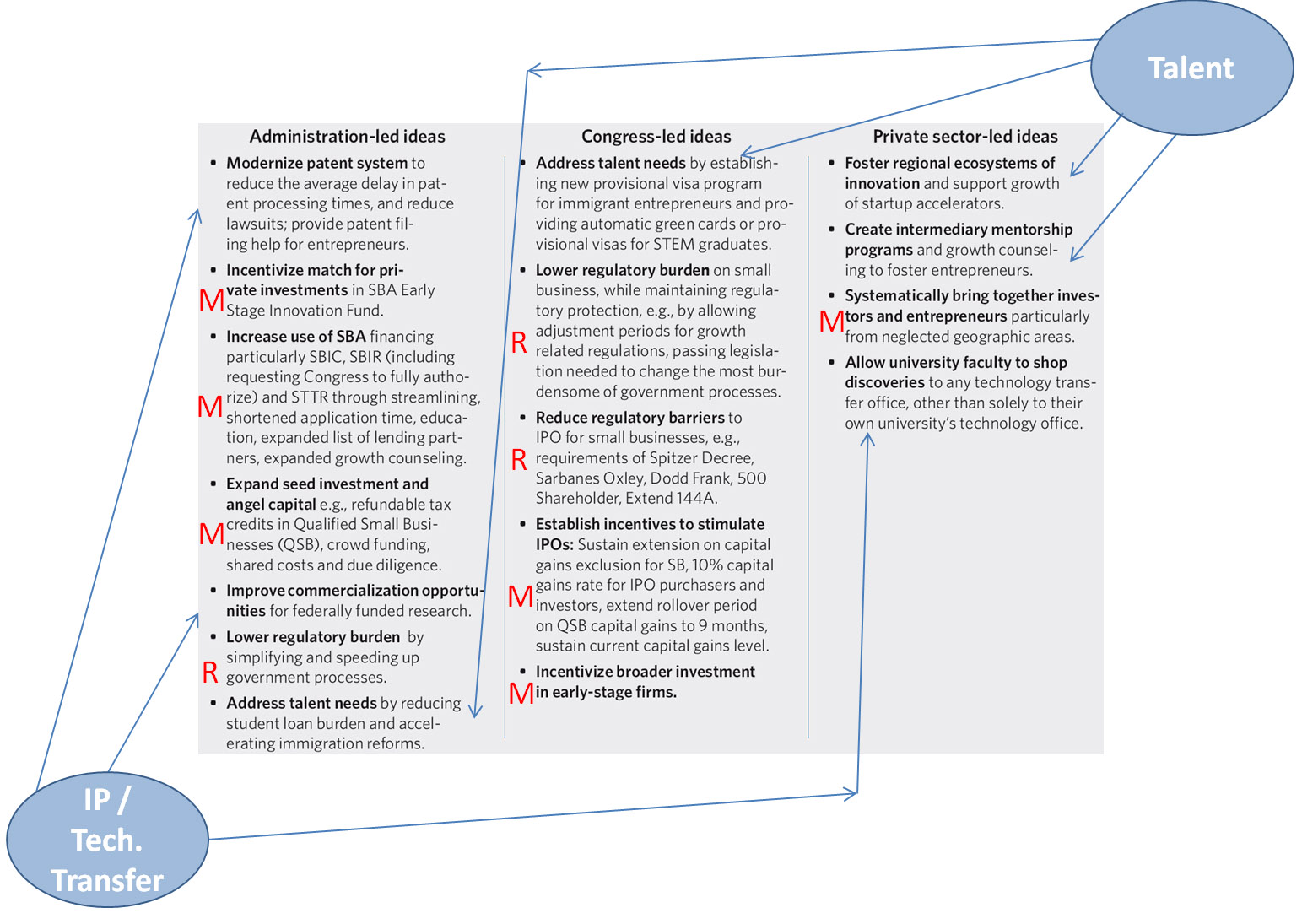

Here is my simplistic vision of the proposals:

– a few are about lowering the barriers, i.e. “changing the Rules”, what I tagged with an “R” below.

– a few more are about enabling more money and investment towards start-ups, tagged with an “M”.

These are classical measures, important and necessary.

What I found very interesting are the other ones:

– three are about Intellectual Property and Technology Transfer, a sign that the patent system might be in trouble

– even more interesting, the last three are about the People, the Talent. They mention the Immigrants and the Mentors.

These are great advice, that we should also look at very seriously in Europe!

Click on the picture to enlarge

Win the Global Battle for Talent

Some of the most iconic American companies were started by immigrant entrepreneurs or the children of immigrant entrepreneurs. Today, however, many of the foreign students completing a STEM degree at a U.S. graduate school return to their home countries and begin competing against American workers. A significant majority of the Jobs Council calls upon Congress to pass reforms aimed directly at allowing the most promising foreign-born entrepreneurs to remain in or relocate to the U.S.

Reduce Regulatory Barriers and Provide Financial Incentives for Firms to Go Public

Lowering the barriers to and cost of IPOs is critical to accessing financing at the later stages of a high growth firms’ expansion. A significant majority of the Jobs Council recommends amending Sarbanes-Oxley and “rightsizing” the effects of the Spitzer Decree and the Fair Disclosure Act to lessen the burdens on high growth entrepreneurial companies.

Enhance Access to Capital for Early Stage Startups as well as Later Stage Growth Companies

The challenging economic environment and skittish investment climate has resulted in investors generally becoming more risk-adverse, and this in turn has deprived many high-growth entrepreneurial companies of the capital they need to expand. The Jobs Council recommends enhancing the economic incentives for investors, so they are more willing to risk their capital in entrepreneurial companies.

Make it Easier for Entrepreneurs to Get Patent-Related Answers Faster

There are concerns among many entrepreneurs that, as written, the recently passed Patent Reform Act advantages large companies, and disadvantages young entrepreneurial companies. The Jobs Council recommends taking specific steps to ensure the ideas from young companies are handled appropriately.

Streamline SBA Financing Access, so More High -Growth Companies Get the Capital they Need to Grow

The SBA has provided early funding for a range of iconic American companies. The Jobs Council recommends that the Administration streamline and shorten application processing with published turnaround times, increase the number of full time employees who perform a training or compliance function, expand the overall list of lending partners, and push Congress to fully authorize SBIR and STTR funding for the long term, rather than for short term re-authorizations.

Expand Seed/Angel Capital

The Jobs Council recommends that the Administration clarify that experienced and active seed and angel investors should not be subject to the regulations that were designed to protect inexperienced investors. We also propose that smaller investors be allowed to use “crowd funding” platforms to invest small amounts in early stage companies.

Make Small Business Administration Funding Easier to Access

The SBA has provided early funding for a range of iconic American companies, including Apple, Costco, and Staples. The Jobs Council recommends that the Administration streamline and shorten application processing with published turnaround times, increase the number of full time employees who perform a training or compliance function, expand the overall list of lending partners, and push Congress to fully authorize SBIR and STTR funding for the long term, rather than for short term re-authorizations.

Enhance Commercialization of Federally Funded Research

The government continues to play a crucial role in investing in the basic research that enables America to be the launchpad for new industries. The Jobs Council recommends that the Administration do more to build bridges between researchers and entrepreneurs, so more breakthrough ideas can move out of the labs and into the commercialization phase.

Address Talent Needs by Reducing Student Loan Burden and Accelerating Immigration Reforms

A large number of recent graduates who aspire to work for a start-up or form a new company decide against it because of the pressing burden to repay their student loans. The Jobs Council recommends that the Administration promote Income-Based Repayment Student Loan Programs for the owners or employees of new, entrepreneurial companies. Additionally, we recommend that the Administration speed up the process for making visa decisions so that talented, foreign-born entrepreneurs can form or join startups in the United States.

Foster Regional Ecosystems of Innovation and Support Growth of Startup Accelerators

There is a significant opportunity to build stronger entrepreneurial ecosystems in regions across the country – and customize each to capitalize on their unique advantages. To that end, the Jobs Council recommends that the private sector support the growth of startup accelerators in at least 30 cities. Private entities should also invest in at least 50 new incubators nationwide, and big corporations should link with startups to advise entrepreneurial companies during their nascent stages.

Expand Programs to Mentor Entrepreneurs

Research consistently shows that a key element of successful enterprises is active mentorship relationships. Yet, if young companies do not have the benefit of being part of an accelerator, they often struggle to find effective mentors to coach them through the challenging, early stages of starting a company. Therefore, the Jobs Council recommends leveraging existing private sector networks to create, expand and strengthen mentorship programs at all levels.

Allow University Faculty to Shop Discoveries to Any Technology Transfer Office

America’s universities have produced many of the great breakthroughs that have led to new industries and jobs. But too often, research that could find market success lingers in university labs. The Jobs Council recommends allowing research that is funded with federal dollars to be presented to any university technology transfer office (not just the one where the research has taken place).