In my post of November 8th, I promised to “read Marion Flécher’s book with great interest and will write to you in a future post to see if I find cause for resignation or optimism regarding the startup world.” I’m going to say both! The book is indeed excellent and perfectly describes the differences between France (which tried to claim to be a Startup Nation) and Silicon Valley (which never felt the need for such a claim).

The Difficulty of Defining the Word “Startup”

The heart of the book is not the comparison between the two regions, but rather what the French startup scene is like; I will return to this point. In her introduction, she explains the difficulty in defining the word, to the point of writing: “Making startups my subject of study was not a given. […] I was encouraged to use alternative terms such as innovative companies, technology companies, or high-growth companies” [page 16]. With a striking analogy, she adds, “as with the art world, in which players spend their time trying to determine what is art and what is not, it is by observing how a world makes these distinctions, and not by trying to make them ourselves, that we begin to understand what is happening in that world” [page 20]. Without naming Steve Blank, through a survey of entrepreneurs who gave her a multitude of definitions, she almost mentions my favorite definition: “a temporary organization in search of a repeatable and scalable business model”.

Silicon Valley, Heart of Startups

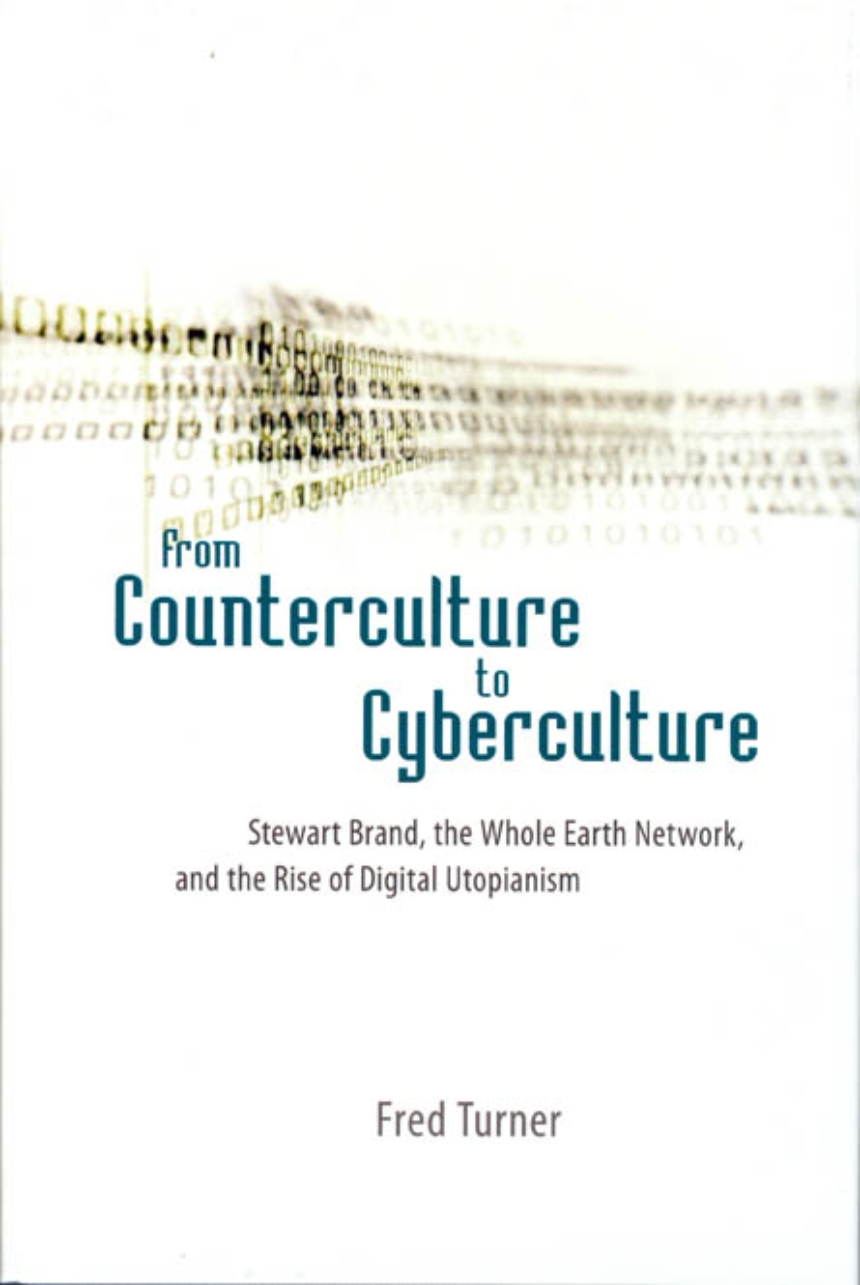

In her first chapter, Marion Flécher describes Silicon Valley, the region that gave rise to the semiconductor, the microprocessor, the microcomputer, software, the internet, social networks (and ultimately artificial intelligence, which had not yet emerged when she conducted her research). She demonstrates that the region was at the heart of a revolution that goes beyond technological innovation. This innovation was “accompanied by organizational and managerial innovations that led to a profound ideological redefinition of the entreprise” [page 52].

Yet, she shows that pinpointing the moment of their emergence is just as difficult as defining startups. “For many historians and ethnologists specializing in Silicon Valley, it is Intel’s invention of the microprocessor that constitutes the true starting point of the region’s technological boom and rise to power” [page 39]. She does not, however, neglect to note the importance of Hewlett-Packard (founded in 1939) and Fairchild (founded in 1957) in this dual revolution, including the development of project-based work in small teams, the upheaval of dress codes, and the implementation of new incentive structures [pages 52-53]. The complexity of the region’s origins also stems from the existence of other significant influences such as free software and the “Do It Yourself” culture [pages 55-56], and from a diversity of major players including venture capital funds, the federal government, and the companies themselves. A world, as the author describes it, an ecosystem.

Another difficulty addressed by Marion Flécher, at least for a Silicon Valley enthusiast like myself, is: when did the word “startup” first appear? “The term ‘startup’ seems to have been used for the first time in 1976, in a Forbes magazine article, to refer to young technology companies in Silicon Valley” [Author’s note: The Unfashionable Business of Investing in Startups in the Electronic Data Processing Field]. “The term ‘startup company’, which associates the startup with a specific type of business, appeared a year later in an article entitled ‘An Incubator for Startup Companies, Especially in the Fast-growth, High Technology Fields,’ published in Business Week in 1977.” The author adds that the term acquired its current meaning and spread worldwide during the 1990s, even though this new business model can be traced back to the 1940s. NB: I confirm this in a blog post: When was the word “start-up” first used?

![]()

Scan of Figure 2 [page 43]: Timeline of the main Silicon Valley technology companies. I circled two things by hand while reading. My surprise at seeing only one founder for eBay; I thought Jeff Skoll was a co-founder, but apparently he may have only been the first employee. And my other surprise at seeing three co-founders for Apple, which is rarely mentioned. Ronald Wayne is often forgotten. And then a rather unimportant note for Marion Flécher: Wo[lk]zniak is misspelled on page 41!

Risk and Uncertainty

In a brief but equally excellent section on venture capital, Marion Flécher explains that “unlike risk, which refers to a situation that can be predicted by probability and in which actors can reason rationally […] uncertainty refers to a situation in which the degree of singularity is such that it cannot be compared to any other. By developing disruptive innovations, Silicon Valley entrepreneurs create situations of radical uncertainty in which actors can only make speculative judgments” [page 46]. This explains why the term [ad]venture capital is very different from the term capital-risque in France (which is undoubtedly indicative of dissimilar worlds). “Nevertheless, these players have resources that allow them to transform the uncertainty of a situation into a quantifiable risk. Their activity requires, first and foremost, a sound knowledge of the technical environment, which enables them to assess the growth prospects of projects. Most investors […] are thus often former engineers or entrepreneurs” [page 47]. This is undoubtedly another major difference between Silicon Valley and France.

Since I mentioned personal surprises in the commentary on the figure above, I take this opportunity to add a few more personal comments (for myself, the author, and any potential reader!):

– Without a doubt, the startup world is a new illustration of capitalism, and this has undoubtedly been misunderstood. Startups have never been liberated companies; trade unions are very rare, not to say unwelcome. I already mentioned this point in my first post.

– Marion Flécher emphasizes intellectual property (Microsoft’s proprietary software, Intel’s microprocessor patent), which creates near-monopolies favored by a state that “seems to have implicitly supported market concentration” [page 49]. Yet it was the state that forced Bell Labs to grant licenses for the transistor, for which the company held the patent. Intel certainly had a near-monopoly on the microprocessor, even though IBM and AMD were genuine competitors. But competition in new sectors has made Intel a declining player in recent years (telecommunications, artificial intelligence). I would say that the US government is protecting the country at a macroeconomic level by defending its technological lead rather than protecting any individual company. OpenAI might replace Google, which could have replaced Microsoft, just as Nvidia or even AMD might replace Intel. The same goes for mobile phones. The US remains the leader.

– Another minor point of doubt: “Between 1998 and 1999, venture capital almost doubled, going from $3.2 billion to $6.1 billion” [page 48]. I have the impression, and I could be wrong, that the amounts were about ten times larger and that these figures correspond more closely to the 1980s.

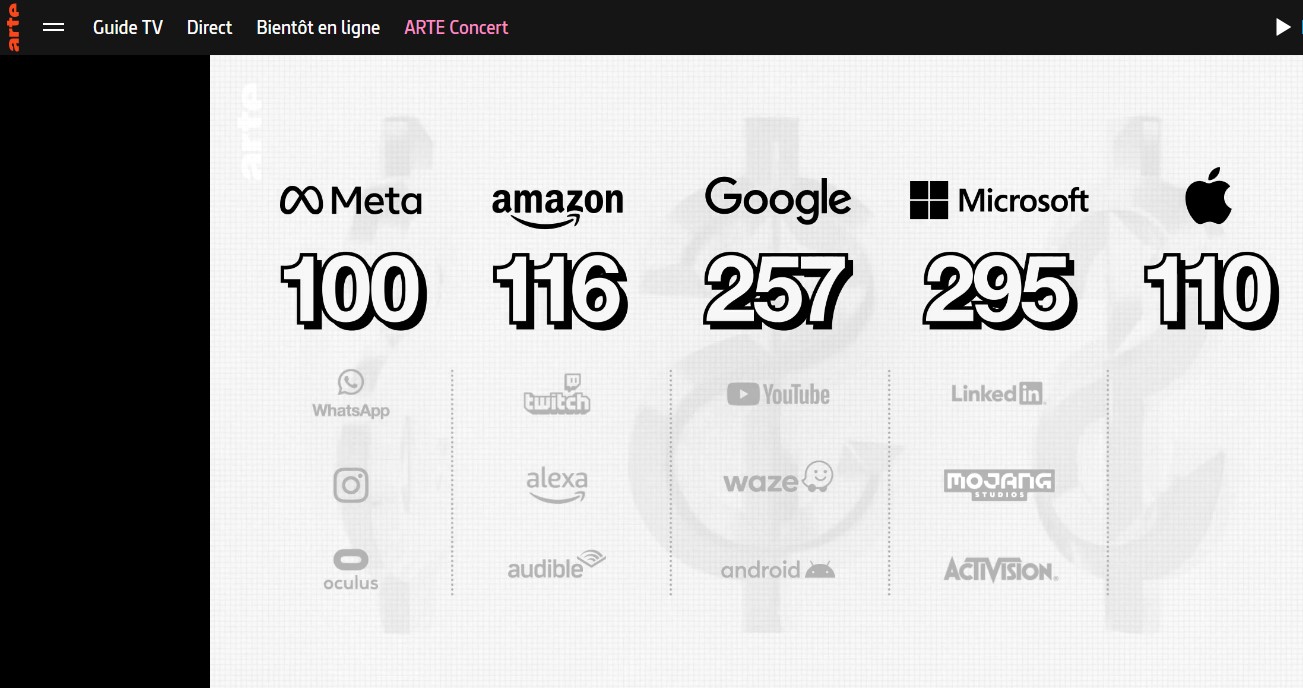

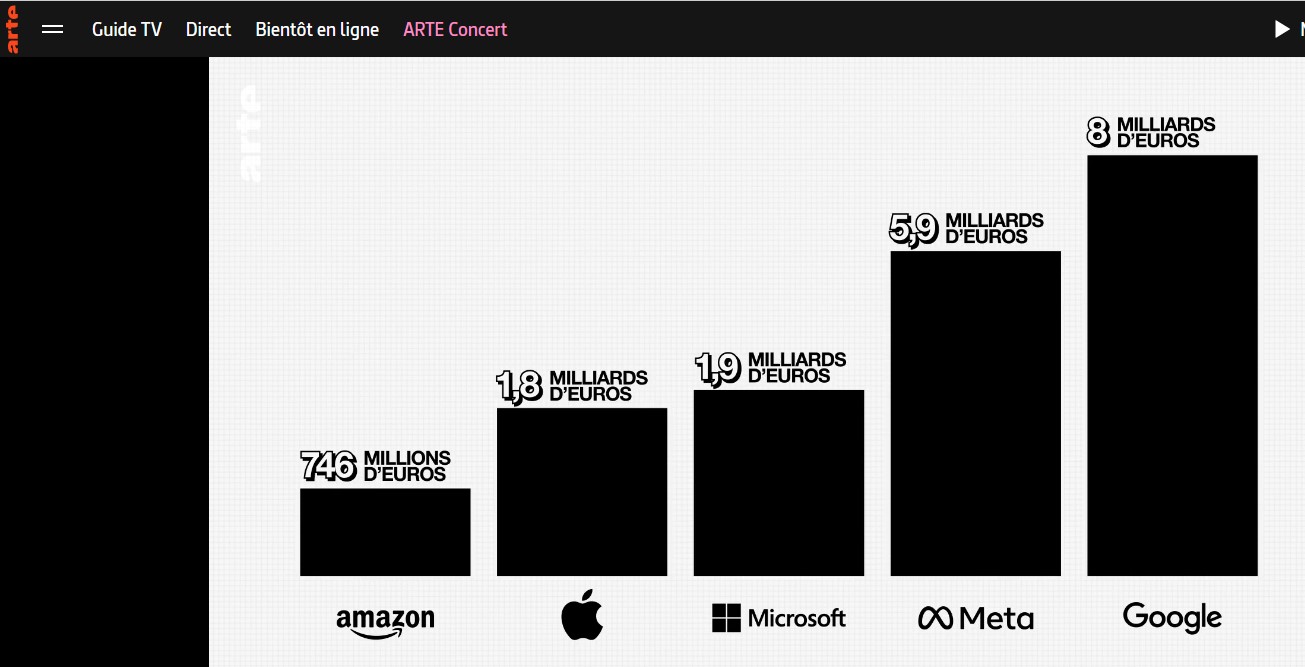

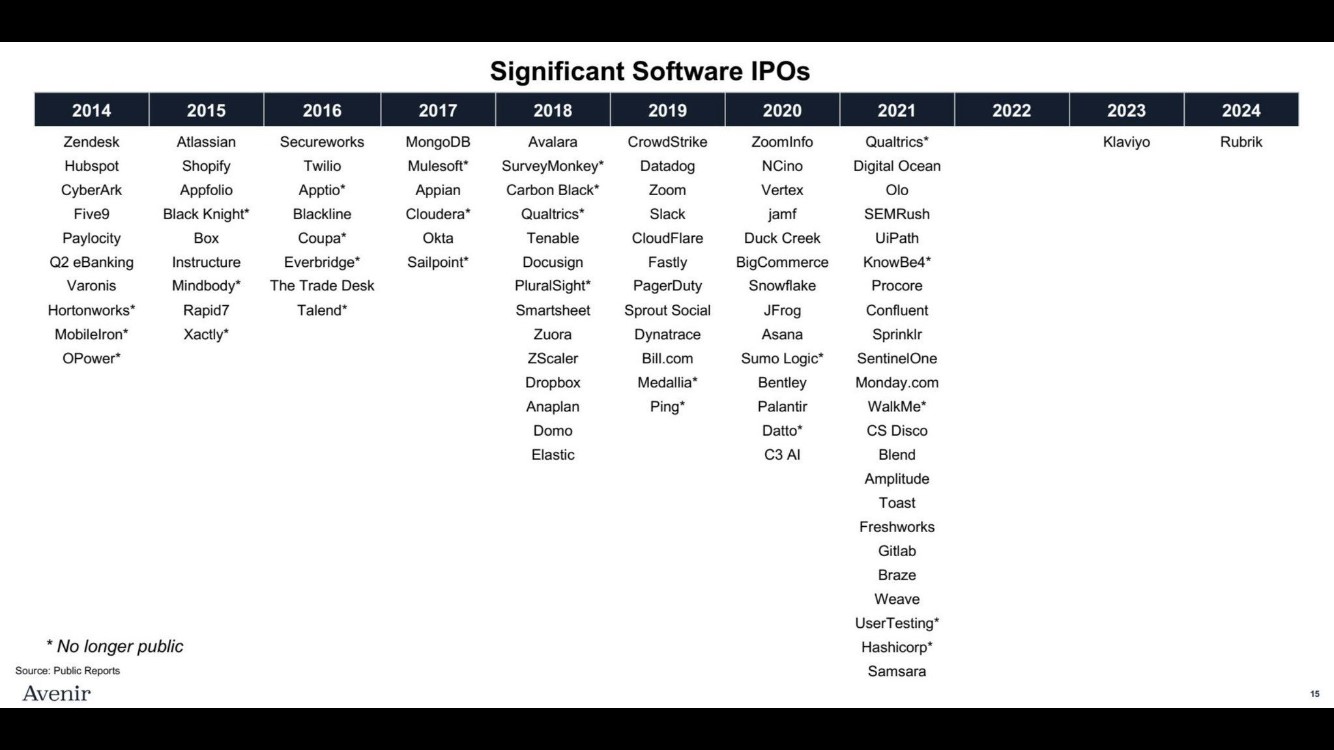

– Finally, I see confirmation of a personal impression regarding the decrease in the number of IPOs: Silicon Valley had 417 IPOs in 2000 compared to only 14 in 2021 [page 51]. Indeed, for years I’ve been compiling market capitalization tables and dreamed of quickly reaching 1,000, but the IPO drought is slowing my ambition… On the other hand, M&A acquisitions still seem as prosperous as ever, since Marion Flécher mentions more than 90 acquisitions by Facebook since its creation (see my posts on Cisco and Google). A startup may not be destined to become a long-term business, but it’s also possible that the monopolistic concentration mentioned above is at its peak…

France, a nation of startups?

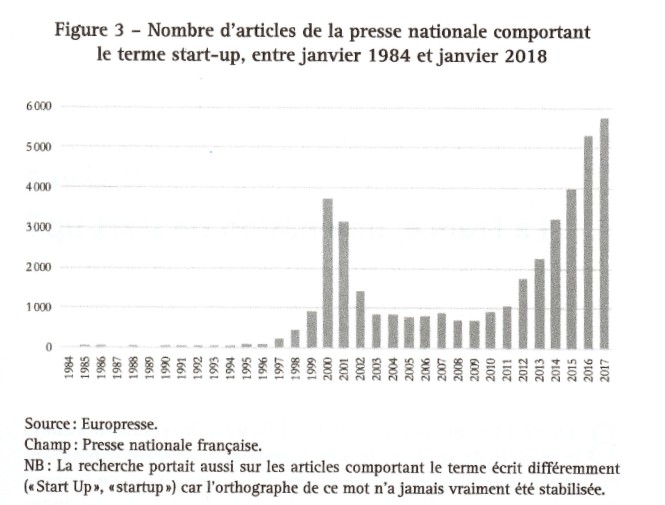

That’s the title of Chapter 2. And the second page of this chapter includes the following figure. It’s easy to see that the French press began to take an interest in the subject during the dot-com bubble and then again from 2012 onwards. Manon Flécher explains that this second period is significant, coinciding with the arrival of Uber and Airbnb in France, but also with the creation of BPIFrance and the French Tech initiative. Equally interesting, the author reminds us that General de Gaulle visited San Francisco in 1960, Georges Pompidou 10 years later, and François Mitterrand in 1984. The author doesn’t mention the creation of Sophia Antipolis in 1969, which Paul Graham mocks, more or less gently (see my post from 2011). Presidents Hollande and then Macron have been apparently much more involved in the topic.

Is France a startup nation? The answer is clear if you’ve read the preceding paragraphs. But the debate runs deeper, as I indicated in *Politics vs. Economics: A Country Is Not a Startup*, translating the article Non, la France ne doit pas devenir une start-up. I didn’t know, or had forgotten, that Emmanuel Macron had then used the term “hyper-innovation.” But the doomsayers are always ignored, and hyper-communication too often trumps reality and facts.

Marion Flécher also addresses this by stating that “despite this growth, the State remains the primary funder of startups in France” [page 71]. Her footnote on page 69 is revealing. “In 2015, business angels reportedly invested a total of €41 million, which was still half the amount in the United Kingdom and 2.5 times less than in Germany. […] In 2023, the United Kingdom continued to lead other European countries with €307.4 million invested by business angels, compared to €198.5 million for Germany and €142.5 million for France.” BPIFrance represents two billion euros in direct investments in company capital [page 72].

My post is already too long, which is convenient since I’m at this point in my reading of Le Monde des startups. Yet I haven’t even started on the main topic: the sociology of startup founders. A sequel coming soon!

Post-scriptum : On a related note, I just bought *Palo Alto: A History of California, Capitalism, and the World*, one review of which says, The most comprehensive — and incendiary — history of the place that we’re ever likely to get. A sweeping and unsparing critique, it’s also well written, frequently surprising and, because history tends to rhyme, increasingly urgent. You may never think about Stanford, iconic tech companies like Hewlett Packard or, indeed, the Valley itself the same way again. I won’t.” LOS ANGELES TIMES

The introduction already haunts me: the author promises to explain that the inhabitants of California, Silicon Valley and Palo Alto have not all forgotten the ghosts that surround them and without which the region could not have become what it is… To be continued!