I’ve already written all the good things I thought of La Tech – Quand la Silicon Valley refait le Monde (Tech – When Silicon Valley Remakes the World) (see my previous post). Here is more.

Olivier Alexandre explains in his introduction that he conducted 147 in-depth interviews. His work is full of testimonies that often say more than, at least as , statistical analyses (the two complement each other wonderfully). Especially since in the second part of the book, the author describes essential but intangible ingredients of Silicon Valley: confidence, luck, social attitudes, for example. So I continue with a few excerpts.

“Google came to us in different ways and everyone will have a different story of how it happened. My version is the following: I started interviewing all the people who had a PhD at Stanford and who continued to work there in the engineering departments. It was about fifty people. They are the best and the brightest. And I asked each of them: Who is the best with the best idea? And almost all of them answered: the two guys who worked on Google. And what’s interesting about this story is that this way of doing things is exactly the same as Google’s algorithm.” [Page 195]

“In 2000, I had the vision of Facebook… But because we didn’t meet the right person, it didn’t work. I tried my luck until the end. It’s the investor’s assistant, who says to you: Sorry, he can’t see you. The guys who succeed, there is timing, perseverance, but also luck.” [Page 210]

“There is no concept of caste here, if you come up with a good idea, you will be able to meet guys, raise funds and sit at the table; I’m a living proof of that: we didn’t know anyone. We did not raise 20 million, ok; but we were given a chance; we screwed up, but that’s our problem. Afterwards, if the question is whether Silicon Valley is a utopia: it is not one, obviously. There are old families, networks of alumni, diasporas, new wealthy people, who help their friends and help each other; of course. But there is still this idea: we do not know you, but we will give you a chance.” [Page 211]

And funnier still, or more tragic: “Here everything is organized in communities… We are the first to suffer from being French abroad. It’s never easy to create a startup, even harder when you’re not at home. We all suffer from this. Because the codes are different. And you need to understand them and you’re not sure you understand them on your own. And it’s useful to meet someone who says to you: You’re not crazy, I’m having exactly the same problem and I think that… And that takes a lot of time. It took me four years. The French are arrogant when they arrive. They are so much that they think they are going to become Americans. It’s: Yes, I don’t want to see French people. So they go to the Americans. But without having the codes… I compare them to Barbapapa [A funny French alien family]. They are intelligent, they know how to adapt, but we still recognize them. On the other hand, he, the Barbapapa, he is persuaded to be a car when everyone knows that he is a Barbabapa. It doesn’t work at all. Me, for four years, it took me that long to first understand that you shouldn’t try to imitate them, and then that I wouldn’t be able to change them. […] Except that the French, he already blends into the decor, that physically, he looks like them, so he will blend into the thing, with an added bonus: subtlety. Which is actually exotic. The French entrepreneurs, the executives of the CAC40 who come here, I tell them: You are Senegalese in boubou who come from your village in the bush. Do you give a damn about guys from the Middle East who come to business meetings in traditional attire? But you are the same. You come in a tie… Have you seen people in a tie here? So you have to accept and tell yourself: I’m a Senegalese who just arrived in Paris, I’m black and I have a shitty accent, I don’t dress like them, and I can’t go back to the village, because otherwise I am the shame of the village, while everyone believes in me. They are the same: they are the light of France; when you realize that, that you are a projected dream in fact, how do you do when you are that guy? Well you reboot. Everything I did before doesn’t count. So it’s not an Italian renaissance. No way. It’s a rebirth, meaning that everything I’ve done doesn’t count. All the people I met no longer count and I have to build a new project and a new identity.” [Pages 208-210]

What is great and pretty amazing with this long excerpt is that Silicon Valley has not changed between the late 80s and 2016 when Olivier Alexandre conducted most of his interviews. The culture is absolultely the same ! (See the Post-Scriptum at the end of the article).

Pages 217 to 234 on the entrepreneurial experience are perhaps the most extraordinary that I have read since the beginning of the book. They should be quoted in full, so all to your readers! It is about roller coasters, the virtues of simplicity and sincerity, and energy capital. The illusion of meritocracy is another topic that brings complexity to the whole picture. With, at the end of the passage, “Gradually the articulation between the individual and the collective tends to be reversed: entrepreneurs become the imprint of their environment rather than impacting it. The company is the main vehicle of their dialectic.”

A permanent evolution in search of talents

In Silicon Valley, companies are therefore characterized by a Proteus syndrome, due to a pressure of constant evolution. […] The belief of Silicon Valley entrepreneurs, managers and investors is that change is not only desirable but also “inevitable”. This horizon of expectation leads to making routines, these devices of predictability at the base of the efficiency of bureaucracies and large companies, objects of rejection. […] This dialectic of desired and organized change poses a series of problems within organizations: remaining effective despite instability, maintaining consistency despite changes.

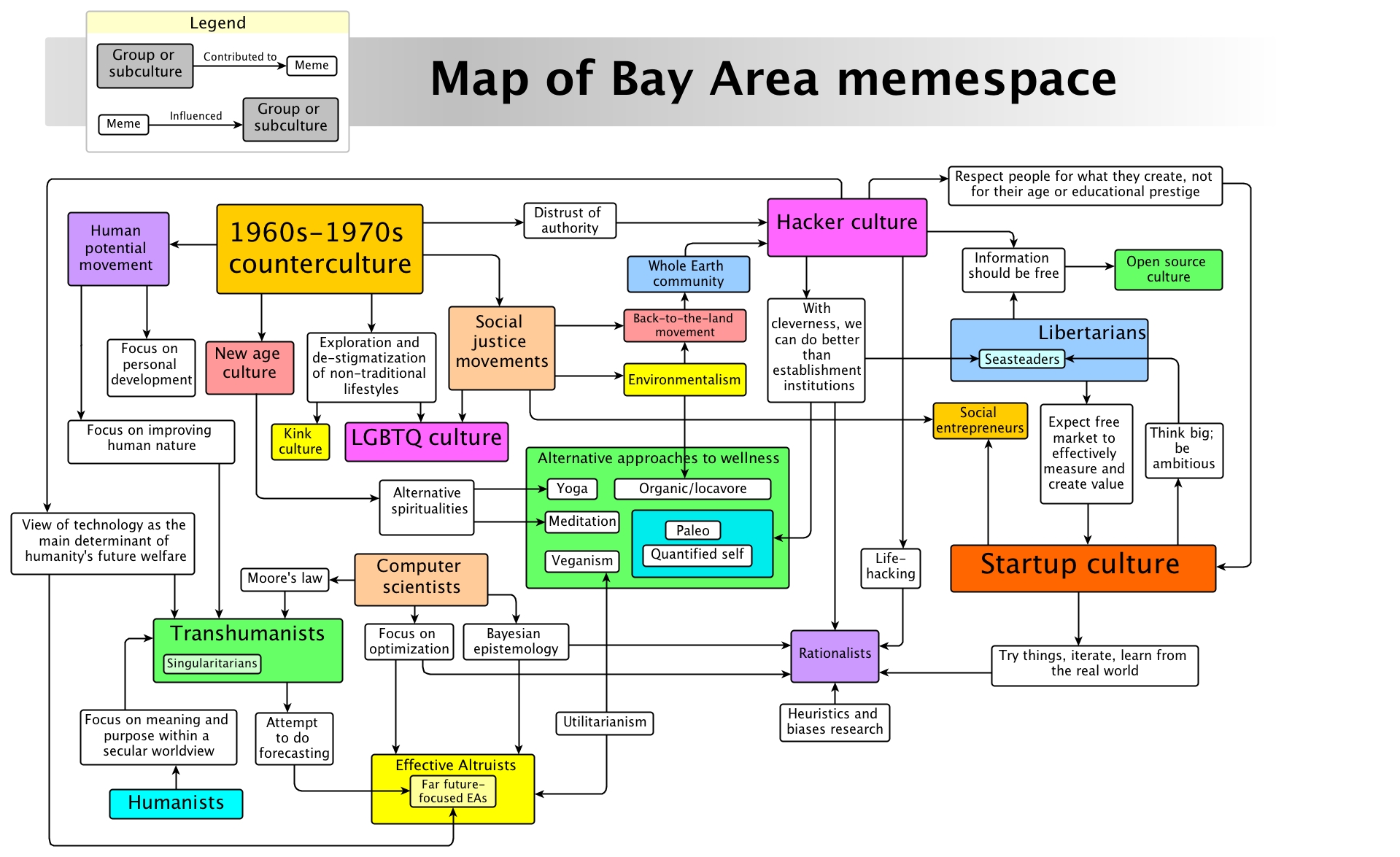

[…] In the sector of new technologies, companies, whatever their size, seek to be innovative. However, innovation presupposes differentiated development phases. The first stages of a project are characterized by phases of trial and error, through tight and close exchanges with users; the usage value remains undetermined. This phase is based on the involvement of enthusiasts, at the crossroads of amateurism, research and the business world, in chiaroscuro spaces, on the border between public space and private space. The cliques formed on this occasion have a number of occurrences in the history of Silicon Valley: amateurs (“hobbyists”) in the field of broadcasting, hackers from MIT fiddling on the sly with DEC and IBM computers, participants of the Homebrew Computer Club in the 1970s, Nolan Bushnell programming his first game “Computer Space” in his daughter’s bedroom before founding Atari, the dormitory brogrammers behind Facebook, etc. After several years, a product with stable properties emerges. A second phase then begins.

The growth in the number of users and the addition of new functions require the involvement of workers with a high level of technical skills. However, developing a solution, increasing its capacities and the number of its applications, solving the problems that arise, are all objectives that require hiring. The profiles sought are designated in Silicon Valley according to a common metonymic name in the fields of creation, “talents”. […] This second phase is decisive in that it suggests a shift in financial terms. The organization is then ready to engage in a third phase, which brings it closer to traditional sectors: an operating technology, a structured and clearly identified market, with means of production, the counterpart of which is a slowed down innovation dynamic. Indeed, once a commercial niche has been invested and marked out, the teams tend towards the systematization of processes and the organization is characterized by effects of bureaucratization. These “slow” development companies (referred to as “slow moving organizations” in Silicon Valley) are often powerful but discredited because the learning effects are limited. To maintain a dynamic of innovation, large companies commonly resort to a so-called external growth strategy, by hiring or buying companies in order to integrate their innovations or their teams. The recent history of large companies illustrates the consistency of this strategy: Apple made 100 acquisitions between 1976 and 2020, Microsoft 225 in forty-five years of existence, Amazon 88 in twenty-five years, Facebook 82 in fifteen years, Google 236 in twenty years, an average of one acquisition per week. During these three phases, the destiny of organizations rests largely on the human factor. [Pages 242-5]

Company cultures

Faced with these constant challenges, it seems that Silicon Valley has developed a rather unique culture. Sincerity and simplicity are mentioned again with the famous pitch: “In presentations, there is a lot of waste, a lot of people don’t know what they are talking about and it is obvious right away. The speech is incoherent and they do not know how to express what they are doing precisely. And that is the first sign that they are going to screw up. They don’t know how to explain in a concise paragraph what they are doing. It is not just a problem of intellectual coherence. Oral and written communication is one of the fundamental skills of a successful entrepreneur. An entrepreneur must be able to raise funds. If he is not able to express clearly, concisely, what he does, why it is interesting and how it is new, he will not succeed” [Page 272].

Clearly establishing a mission makes it possible to stay on course whatever the circumstances and for the long term, by providing motivation to overcome difficulties, put suffering into perspective and make choices [Page 270]. Could this be an explanation to the quasi-absence of workers’ unions?

However, every company is different, even within the same sector. The openness and flow of information at Google, networking at Facebook, competition at Uber, design at Apple, etc. […] In the 2010s, Lyft made a name for itself by promoting a culture of openness and inclusion, in contrast to Uber [Page 268].

With some risk: “Company culture is our own spiel in Silicon Valley. […] But it’s still bullshit in the sense that it quickly becomes artificial if it’s not embodied. The thing is carried by the founder and it works as long as he is there, he is the one who embodies it, who carries it. […] But the day he leaves, values become boxes in an evaluation grid” [Page 283].

Post-Scriptum: personal notes related to the second part of the book.

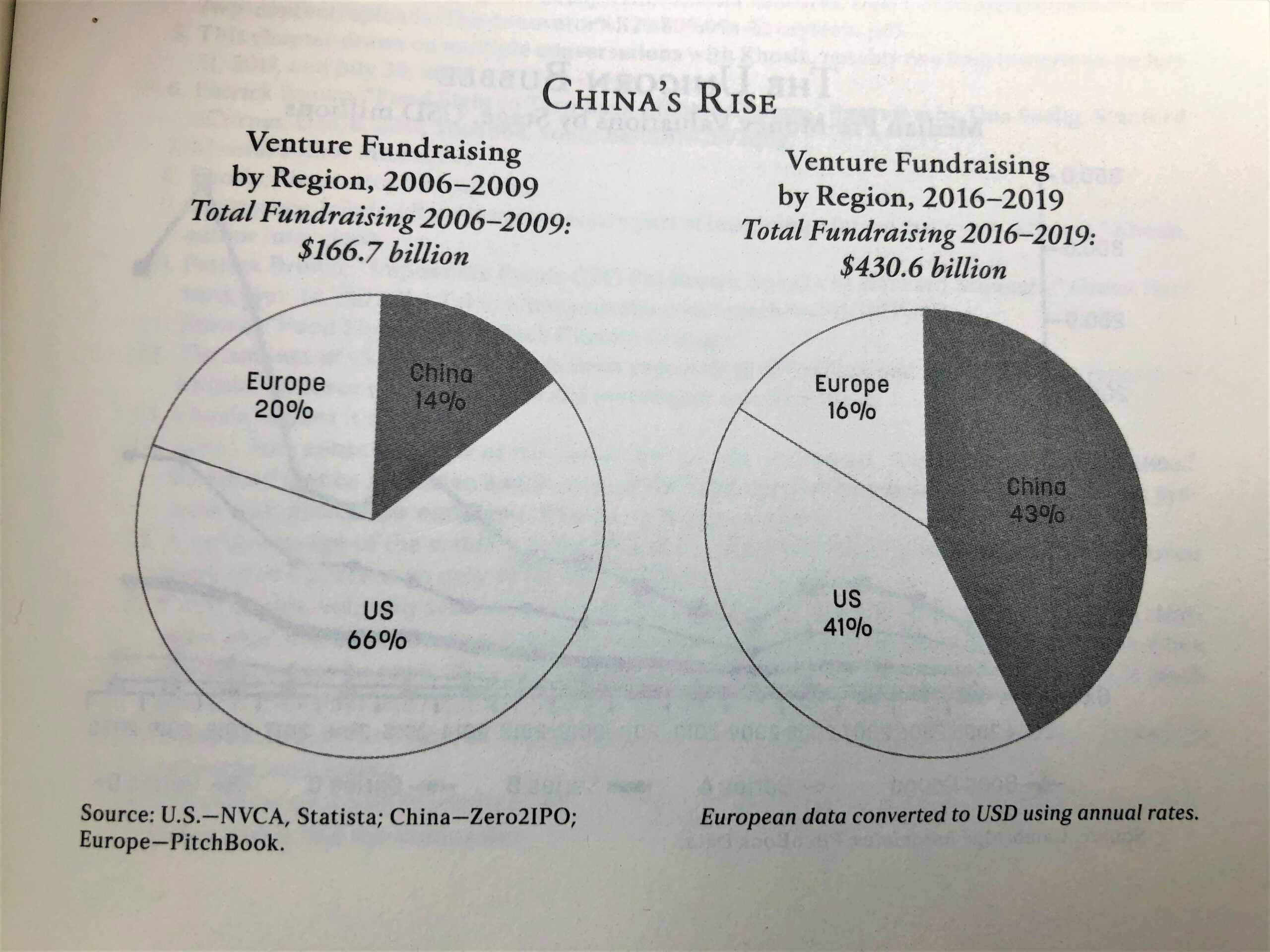

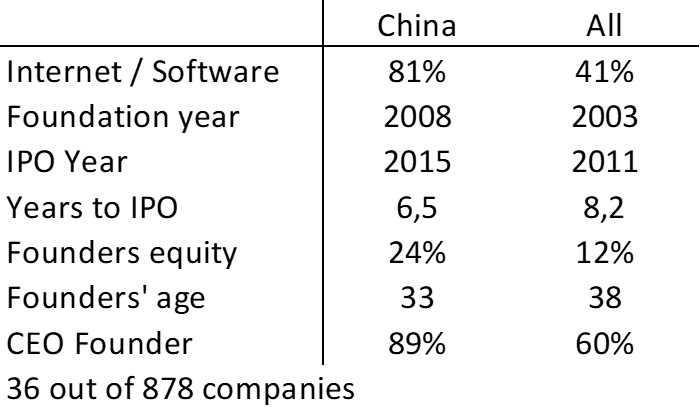

– Olivier Alexandre gives very interesting statistics, especially on pages 170-72. I mention my own data on startups from Stanford or other startups that have prepared an IPO on this recent post. On the age of the founders – 45 years old -, the number of founders – 75% are more than 3 – or on the serial entrepreneurs – 60% are, I have built similar data sets.

– For those interested in the topic of startup acquisitions (M&A), here are two blog links: Cisco’s A&D and Google in the Plex. An additional link show that even public companies are often acquired.

– But as I said before, statistics are one thing. The description by a multitude of cases is another and the two complement each other perfectly, I believe. I remembered a trip to Silicon Valley in 2006. The report we made is confidential because of the non-anonymized testimonies. But I extract the non-secret part:

06-05-Trip in the Silicon Valley-FILTERED