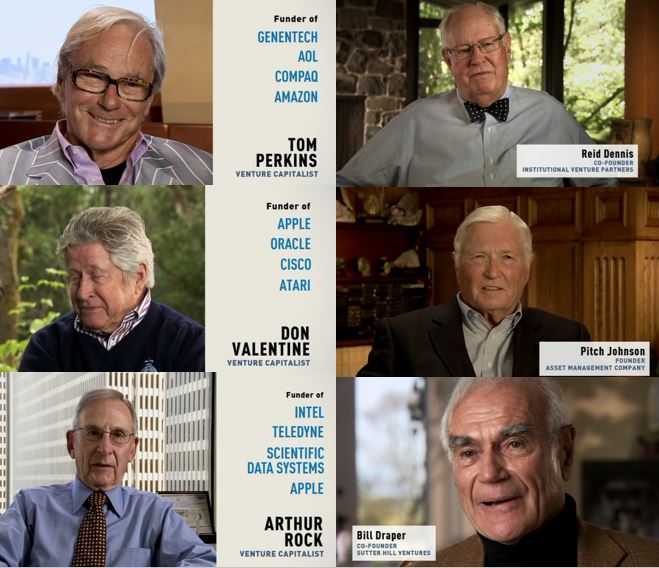

This morning, I was participating to a workshop about startups and one question came about the relationships with investors entrepeneurs are trying to attract and invest in their company. I told them it could be frustrating for many reasons, often because VCs never say no but decline too often to invest too. The best illustration comes from Something Ventured, a documentary movie I never stop celebrating. The Apple case is close to being hilarious. You find the extract beginning around minute 51 in the video:

and here is the text: [Narrator] In 1976, the computer was about to get personal. […] For venture capitalists, this represented the opportunity of a lifetime.

[Perkins Chuckles] We turned down Apple Computer. We didn’t – We didn’t even turn it down. We didn’t agree to meet with Jobs and Wozniak.

[Reid Dennis] Oh, that would have been a fabulous investment if we had made it, but we didn’t. We said, “Oh, no, we’re not really in that business.”

[Pitch Johnson] “How can you use a computer at home? You’re gonna put recipes on it?”

[Bill Draper] I sent my partner down to look at Apple. He came back and he said “Guy kept me waiting for an hour, and he’s very arrogant.” And, of course, that’s Steve Jobs! I said, “Well, let’s let it go.” That was a big mistake.

[Narrator] In 1976, the only people who believed in the personal computer… were the geeks and nerds who gathered at Homebrew Computer Clubs.

[Bushnell, founder & CEO of Atari] They needed an investment, and, uh, they offered me a third of Apple Computer for $50,000… and I said, “Gee, I don’t think so.” I could have owned a third of Apple Computer for $50’000. [Sighs] A big mistake. But I said, “Call Don Valentine.”

[Valentine] So we had our meeting. I went to Steve’s house. And we talked, and I was convinced it was a big market… just embryonically beginning. Steve was in his Fu Manchu look, and his question for me- “Tell me what I have to do to have you finance me.” I said, “We have to have someone in the company… who has some sense of management and marketing and channels of distribution.” He said, “Fine. Send me three people.” I sent him three candidates. One he didn’t like. One didn’t like him. And the third one was Mike Markkula. Mike Markkula worked for me at Fairchild before he went to Intel.

[Markkula] I said, “Okay.” ‘Cause that’s what I did on Mondays. I was retired. [Chuckles] I think I was 32 when I retired from Intel. But one day a week, I would help people start companies and write business plans. I did it for free, just for the interaction with bright, uh, people… So I went over and talked to the boys. [Laughs] The two of them did not make a good impression on people. They were bearded. They didn’t smell good. They dressed funny. Young, naive. But Woz had designed a really wonderful, wonderful computer. […] And I came to the conclusion that we could build a Fortune 500 company in less than five years. I said I’d put up the money that was needed.

[Narrator] Mike Markkula came out of retirement, becoming the president and C.E.O. of Apple. And the first call he made was to Arthur Rock. Arthur would have missed Apple if it weren’t for Mike Markkula.

[Rock] Jobs and Wozniak came up to see me, and they were very unappealing. Goatee, long hair [Muttering] Markkula said, “Well, before you make up your mind, there’s a computer show. You ought to come down and see what’s going on.” And he did. He thought somethin’ was happenin’. He wasn’t quite sure what. And there was this booth with everybody around it. I couldn’t even get next to it. And it was the Apple booth.

Then I got a call from Don Valentine. [Chuckles] “I want to put some money in that company” I said, “Okay, you gotta come on the board then.”

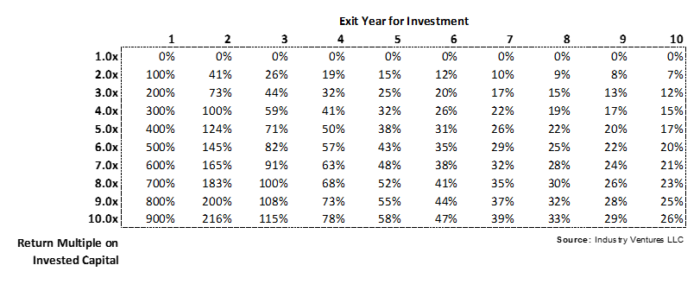

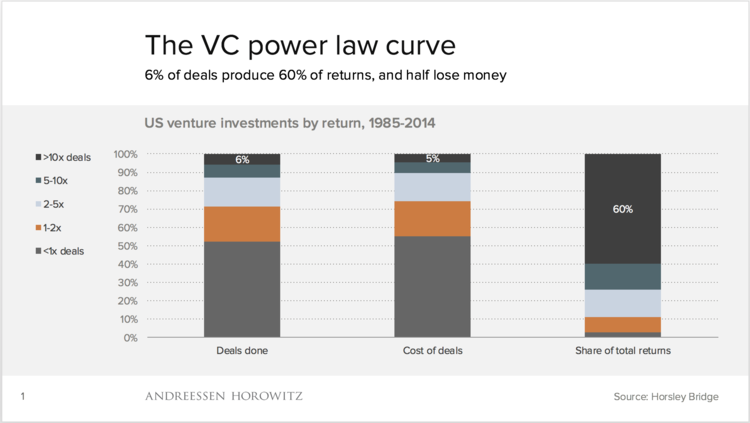

You know in the venture capital business, if you look at 200 deals, and you, you might do 10 of’em, and you will think they’re all great, and if one of’em is great, then you’re in the hall of fame.

Just in case, a little more about something ventured from my blog in 2012: https://www.startup-book.com/2012/02/08/something-ventured-a-great-movie/.

Finally, let me remind you of other “missed deals” in another recent post: The amazing challenge of finding great startups.