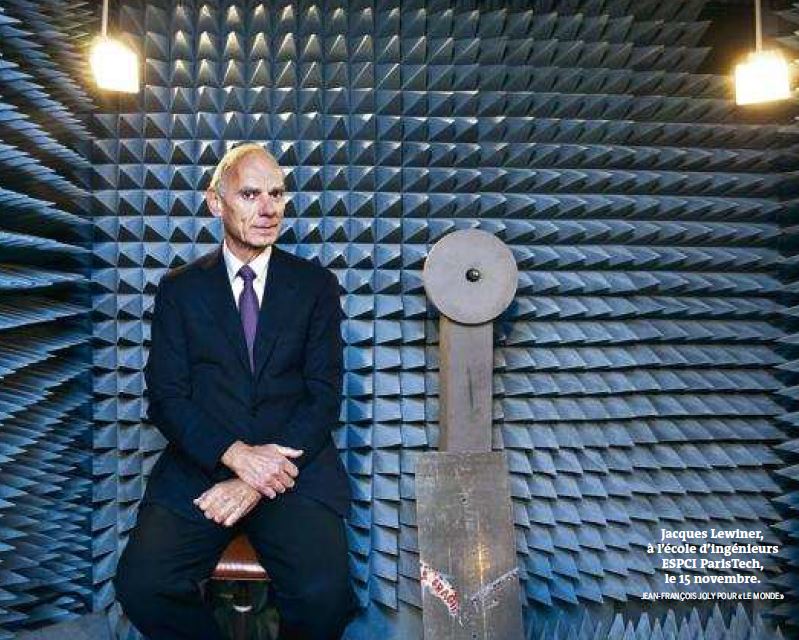

I had the chance to meet this afternoon Jacques Lewiner, the renowned French professor and entrepreneur, who has contributed a lot in making ESPCI a completely atypical engineering school in the French landscape. This is probably the school that “innovates” the most, especially through its spin-offs.

No need to tell you much about the meeting because all his messages can be found in an excellent interview he gave to the newspaper Le Monde last November entitled “In France, there is a huge potential for innovation.” The article is online (and for a fee – it seems) but there is also a pdf document available, both in French. Allow me then to provide my translation below. His philosophy is simple: encourage and encourage again, with a lot of flexibility; in particular, we must strongly encourage entrepreneurship with Silicon Valley, Boston and Israel as models.

An anecdote before I let you read the interview: he enjoyed reminded me several times that his vision did not make him only friends, as he thought the proximity to the industry and flexibility are essential. But he told me he was the successor of a famous lineage with a similar philosophy: Paul Langevin was a renowned scientist, inventor and author of patents on sonar and… a communist. ESPCI was founded by engineers concerned about the weakness of France and its universities in chemistry after the loss of Alsace and Lorraine in 1870. The Protestant culture of its founders facilitated perhaps closer links between academia and industry. (See History of the Graduate School of Industrial Physics and Chemistry of the City of Paris in French again.)

“In France, there is a huge innovation potential”

For the researcher and entrepreneur Jacques Lewiner, we must fight the idea that research does not support the creation of wealth. Jacques Lewiner is Honorary Scientific Director of ESPCI ParisTech engineering school. This former researcher with “a thousand patents” (taking into account the many countries where patents have been filed) is also the head of the Georges Charpak ESPCI endowment intended to help researchers to put their ideas into practice. He is also the Dean of the valorization at Paris Sciences and Letters (PSL), a new entity bringing together several academic institutions. In addition to his research career, he created or co-founded many companies, including Inventel (Internet box manufacturer) Finsecur (fire safety) Cytoo (cell analysis) and Fluigent (fluid management).

What do you mean by innovation? This is what transforms the knowledge acquired – through study, imagination, research … – into a product, a process, a new service. Among this knowledge, those from the research have a very strong leverage. But innovation does not necessarily give a Nobel Prize. And conversely, intellectually beautiful ideas can be of no industrial interest! For example, I was convinced of the value of the piezoelectric plastic materials for which a voltage appears when distorted. I have filed patents and thought that these devices would be used everywhere. It was more than twenty years ago and it is still not the case. Only a few car seats have been able to detect thanks to them the presence of a passenger … In fact, often, the ingredients of an innovation are already around, but it lacks someone to put them together. When we designed the first Internet box with Eric Carreel, creating Inventel, there was no rocket science. We just had the idea of putting in one device a modem, a router, a firewall, a radio interface… It was also very difficult to convince operators of the interest of such a device but, fortunately for us, Free arrived and opened the market.

You did not always meet with success, as shown in the adventure of the first e-book, available from Cytale who filed for bankruptcy in 2002. What lessons did you learn from these failures? By definition, innovation means taking risks. Nothing is taken for granted. In case of failure, we must analyze the reasons and win an experience that others do not. It is enriching. I also remember very well my first failure. I was convinced to have found new properties of “electrets”, the electricity equivalent of what the magnets are in magnetism. I finally realized that they were already known for over a century. However, they could enable the design of new sensors, especially microphones. I tried to convince large corporations by contacting their research center, and not their business units. It was a mistake. These laboratories had obviously no interest in defending an invention that they had not made! I then had the chance to meet a remarkable entrepreneur, Paul Bouyer, with whom I could create my own business. The future was opened to us, but I did in record time all possible errors. I wanted to do everything myself, without understanding the importance of team work. The adventure lasted a year …

Where is France in terms of innovation? It has a huge potential. People are well trained and research is of quality. The basic culture is in place. But there are too many barriers between scientific discovery and the application that will appeal to the market. Our system blocks initiatives. We must simplify French law and do away with some nonsense.

Which ones? Before the 1999 Allegre law, a researcher could not even get into a board! That changed but nonsense persists. Today, it is very difficult for a researcher to become a consultant, the authorization may be received at the end of a very long time, sometimes a year, and, in addition, it has to be out of its filed of competence! Fortunately, some resourceful people manage to get by, but it is an obstacle for most. A ESPCI ParisTech, to help our researchers, we have created an endowment fund. We make strong efforts to answer within two weeks to a researcher who claims an invention. In some institutions, this response may take from six months to eighteen months! Such a delay is likely to delay the scientific publication of the researcher. One could imagine a rule that states that beyond two months no response means agreement.

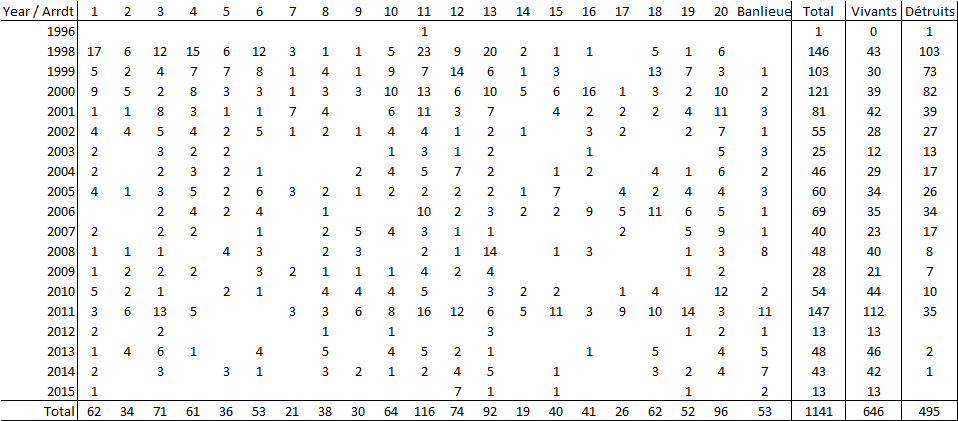

Are patents necessary? Yes, they are useful in two ways. On the one hand, they avoid if successful innovation is copied and, secondly, they secure investors at a fundraiser. But patents can sometimes be like mirages. CNRS has long received many patent royalties from Pierre Potier’s antitumor drugs Taxotere and Vinorelbine. But when the public domain, these patents do not bring any revenue. [In 2008, they accounted for 90% of CNRS royalties]. To create wealth from research, we must also encourage the creation of innovative companies. At ESPCI ParisTech, we help in patenting but also in the creation of start-ups, by granting them very favorable terms in exchange for 5% of their capital. It is a model of operation similar to that of Stanford University [in California], which portfolio of ownership in start-ups (like Google) represents more income than from patents. Some universities charge a 10% to 25% ownership in start-ups, and further require the repayment of loans. It is far too greedy and discouraging for researchers. A few years ago, the Ecole Centrale estimated that its start-ups had generated a ten-year cumulative revenue of € 96 million. For ESPCI ParisTech, over the same period, it was 1.4 billion. And for the Technion Institute in Israel, it was 13 billion in 2013. Do not tell me you cannot do the same in France!

Maybe is it a question of culture. Can we change it? One should not oppose research and creation of economic activity. But it is true that in France sometimes persists the idea that researchers should not benefit financially from their work. However, it is not shocking that good research also creates economic wealth. We must create a favorable ground leaving the most possible freedom for researchers. We can also improve the training of researchers and engineers. Stanford University and the Technion are also models here. The former, with its Biodesign Center, promotes the mixing of cultures between physicists, chemists, medical doctors, biologists, computer scientists… As part of their curriculum, students are required to file a patent, or even start a business! At PSL, we have created with this in mind a new curriculum, the Institute of Technology and Innovation, in which research and innovation are mixed.

Many economists are pinning their hopes on the digital world to boost growth. What about you? Of course, the digital world will have its place in the future as it will be used in all activities. Sometimes we assimilate the digital technologies and the Internet start-ups. The latter sometimes have phenomenal success, sometimes ephemeral. Many fail. The area that can benefit directly from the research is the industrial sector, creating jobs and activities. Have we reached the peak of development and innovations? Certainly not. On the contrary, a new world is opening for the next generations at the confluence of chemistry, physics, biology, electronics and information technology. All this will continue to result in improved quality of life. Let’s not put artificial obstacles on this path and therefore be optimistic about the results that will follow.

Interview by David Larousserie

Le Monde, November 23, 2014.