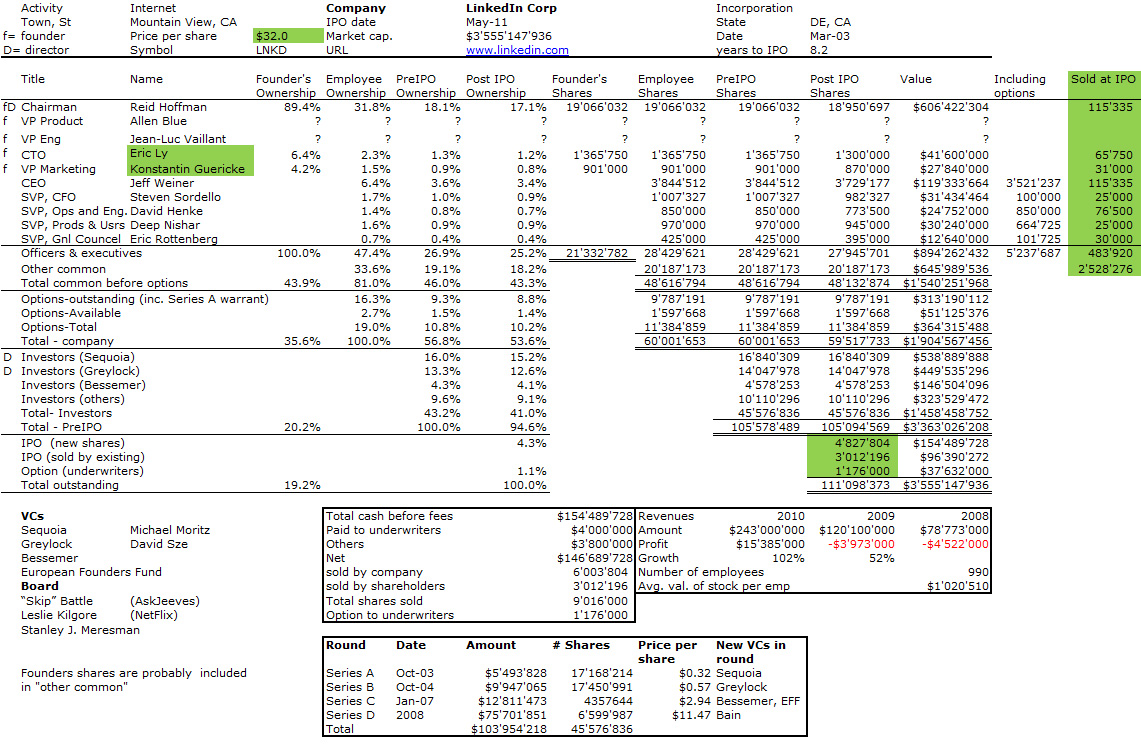

Silicon Valley is well known for its immigrants, particularly those from Asia (India, China, Taiwan, Korea, etc). AnnaLee Saxenian is famous for her books on the topic. The European migrants are lesser known and I think it is a little unfair. Let me first illustrate it with famous examples and then with statistical data.

I have been using this picture for some years now to show that Europe also counts famous Silicon Valley migrants that should be used better as role models. Do you know them? Take a little time to check how many you know and then have a look at the answer.

First row

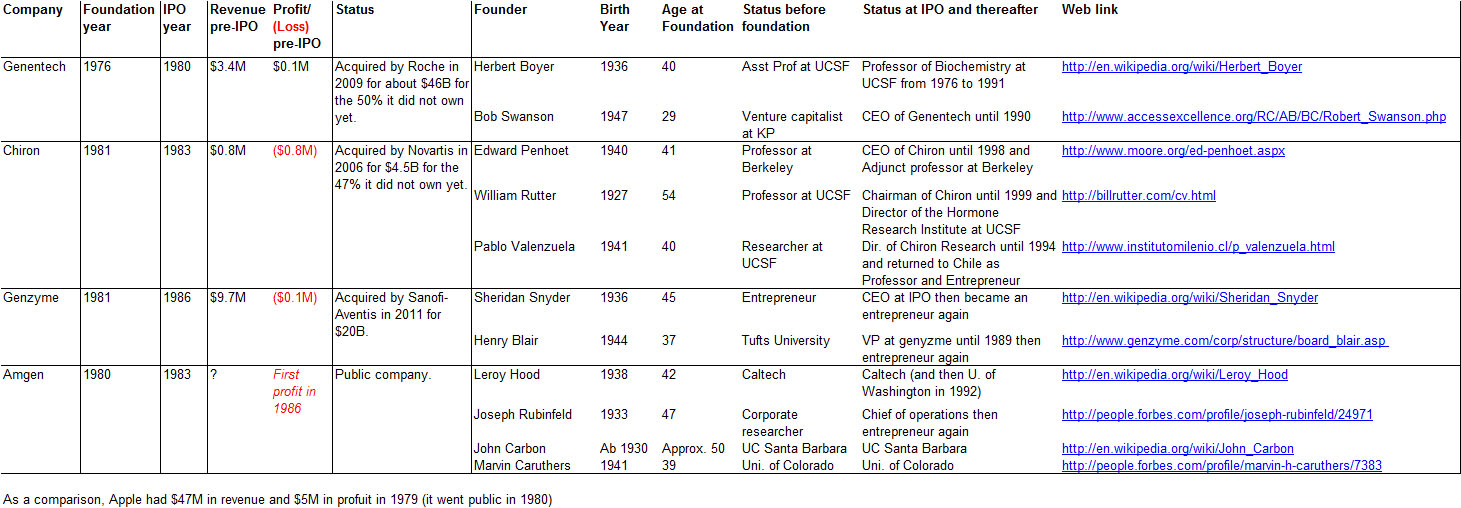

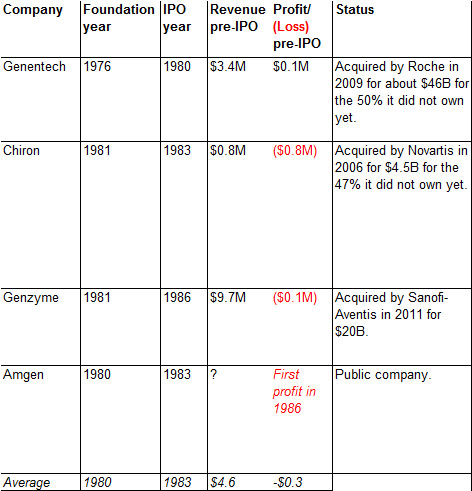

On the top left, here are the famous Traitorous Eight, the founders of Fairchild in 1957 who can be considered as the fathers of Silicon Valley. Jean Hoerni was from Switzerland, Eugene Kleiner from Austria, and Victor Grinich’s parents from Croatia (he was born Grgunirovich). You may want to know more at https://www.startup-book.com/2011/03/02/the-fathers-of-silicon-valley-the-traitorous-eight.

On the right is Pierre Lamond, founder of National Semiconductor and then a partner with Sequoia Capital. As you may imagine, he is a specialist of semiconductors. More at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pierre_Lamond.

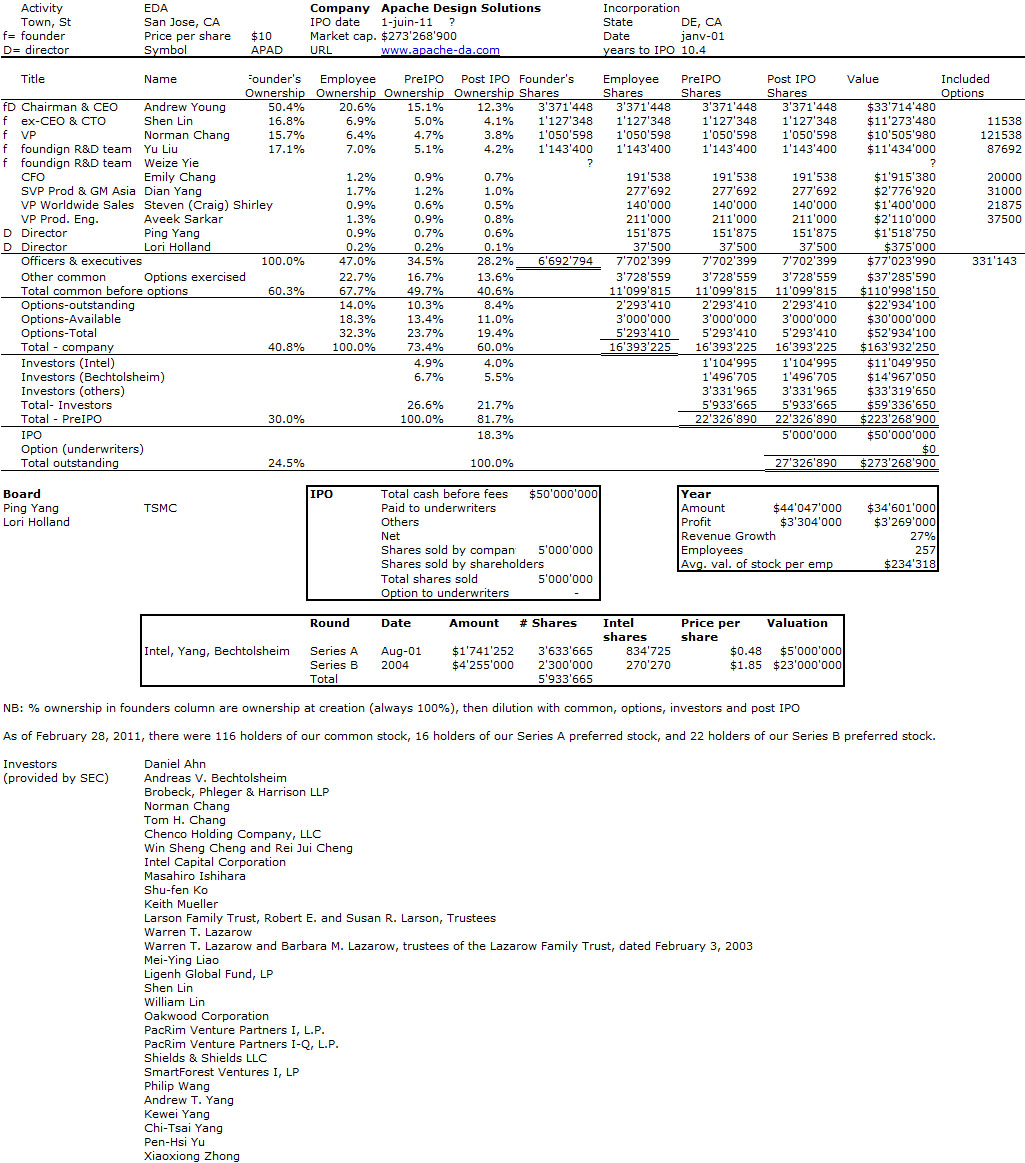

Then comes Andy Bechtolsheim, from Germany. A founder of Sun Microsystems and a business angel in Google (there is the legend he wrote a $100k to Google whereas the company did not exist yet ; a good investment, worth more than $1B a few years later !). http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andy_Bechtolsheim

Finally on the top row is Michael Moritz, from Wales. He was a journalist with Time Magazine when Don Valentine hired him at Sequoia. A good choice, just for two investments he made, Yahoo and Google… http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_Moritz

Second row

Philippe Kahn is probably less famous except in France where he was an icon in the 80’s. He left his motherland when he understood his work would not be appreciated and flew as a tourist in 1982 to the USA. A few months later, he founded Borland. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philippe_Kahn

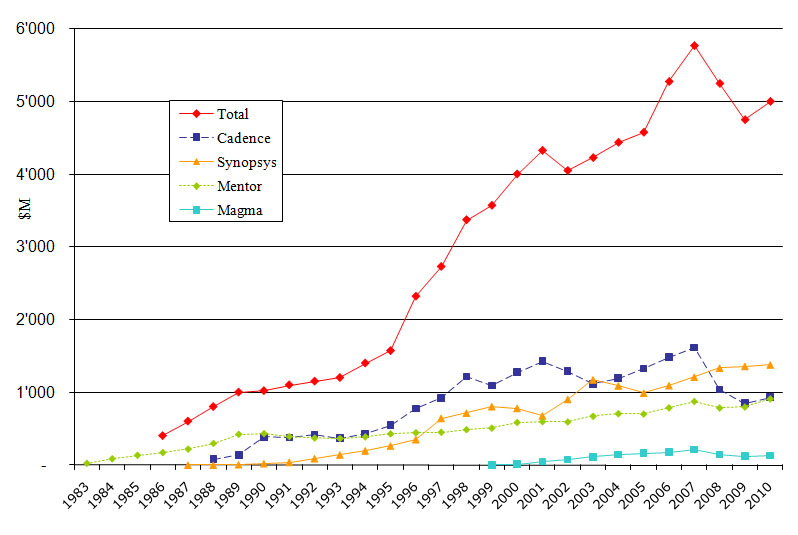

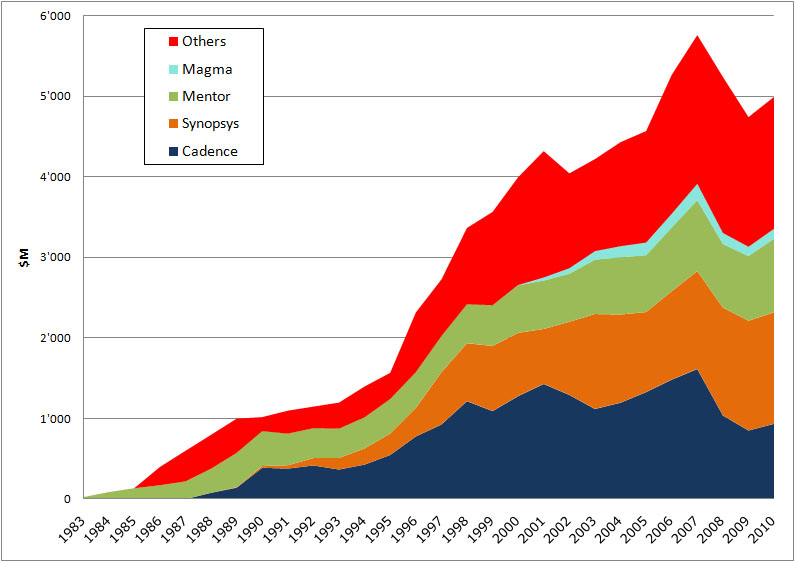

The Dutchman is Aart de Geus. He did his undergrad at EPFL where I work and his PhD in the USA. He is the founder and current CEO of Synopsys, the leader in Electronic Design Automation (6’700 employees, $1.4B in revenue). https://www.startup-book.com/2009/12/11/a-european-in-silicon-valley-aart-de-geus/

Andy Grove flew Hungary under the Communist regime and arrived in New York without speaking English. He can be considered as a founder of Intel and would later become its CEO. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrew_Grove

Third row

Pierre Omidyar, half French, his family has Iranian roots but he was born in Paris, moved to the USA when he was 6… founder of eBay. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pierre_Omidyar

Serguei Brin, founder of Google, born in Moscow, also moved in the USA when he was 6. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sergey_Brin

Edouard Bugnion, from Switzerland, is a founder of VMware. More on https://www.startup-book.com/2010/03/16/a-swiss-in-silicon-valley/

The last examples have more of a Europe-USA-Europe background:

The three founders of Logitech are Daniel Borel, Pierluigi Zappacosta and Giacomo Marini. “The idea for Logitech was spawned in 1976 at Stanford University, in Palo Alto, Calif. While enrolled in a graduate program in computer science at Stanford, Daniel Borel and Pierluigi Zappacosta formed a friendship that would become a business alliance. While completing their education, Borel, a Swiss, and Zappacosta, an Italian, identified an opportunity to develop an early word-processing system (therefore the name which means Software Technology in French). The pair spent four years securing funding and eventually built a prototype for the Swiss company Bobst.” The rest is history.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daniel_Borel

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pierluigi_Zappacosta

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giacomo_Marini

Some similarities with the next story: Bernard Liautaud studied at Stanford before working for Oracle in Europe. A founder of Business Objects with Denis Payre who moved very early in the USA as he had understood that IT = USA. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bernard_Liautaud

Pierre Haren, founder of Ilog, got his PhD at MIT. No Silicon Valley here but Pierre told me once the importance of the American culture in his entrepreneurial venture. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ILOG

I finish with Loic Lemeur, a friend of Sarkozy, who has left France to launch Seesmic in SV. One of the latest European migrants who show that the flow never stops. https://www.startup-book.com/2010/06/21/why-silicon-valley-kicks-europes-butt

🙂 or 🙁 ?

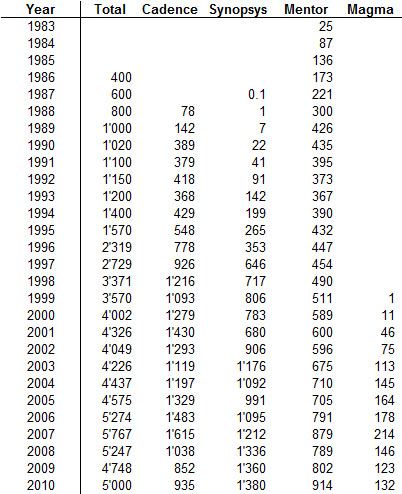

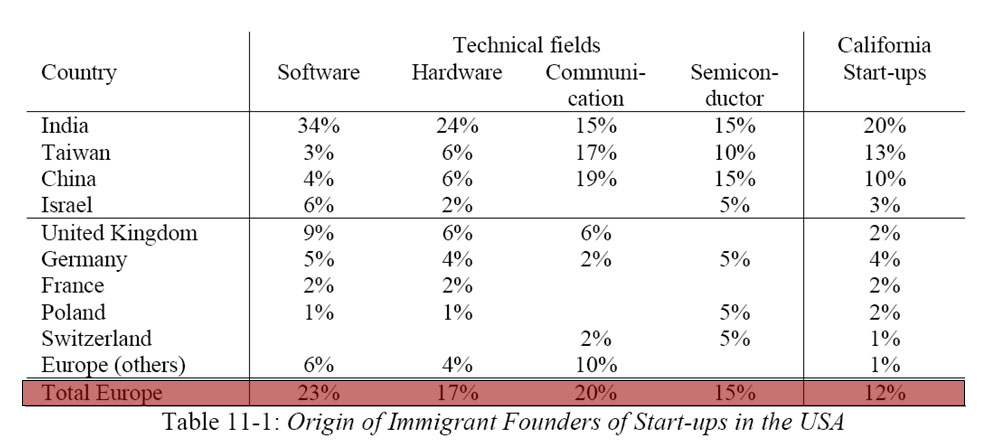

Now the stats. One could always argue that those were only a few examples / exceptions. The table which follows is in my book but comes indirectly from a study by AnnaLee Saxenian. She and her co-authors analyzed where were SV foreign entrepreneurs coming from.I do not think they had compiled Europe as a group which I did from her data. The result is quite impressive because Europe is very similar to China or India. I am not sure this is that well known…

Source: AnnaLee Saxenian et al. “America’s New Immigrant Entrepreneurs” Duke University and UC Berkeley, January 2007.