Well who am I to predict the future? In fact I do not know but I really doubt it. Famous bloggers have mentioned the topic again recently. In Techcrunch it was Can Russia Build A Silicon Valley? by Vivek Wadhwa. And in the Equity Kicker, it was Building an ecosystem to rival Silicon Valley by Nic Brisbourne. I reacted to both in the following way:

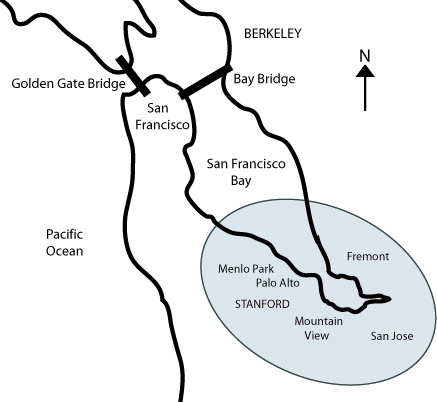

What a topic! Clearly something which has been around for… at least 35 years (I mean how to replicate SV). The fact that we still discuss it shows how complex it is. It has been my main concern in the last years and for the beauty of the debate (that’s what blogs are about, right?) let me play the devil’s advocate fully. At an extreme, I do not think there will ever be another Silicon Valley. For example, Kenney claims in his book on SV it requires 5 basic ingredients: universities of high caliber (Stanford and Berkeley in SV), a strong investor base, service providers, high-tech professionals (who accept to leave their big companies for start-ups so from Intel, Cisco, Apple, MSFT, even Google now to the next wave) and last but not least an entrepreneurial culture. All this is not easy to gather. But even worse, SV was probably an accident, a monster which was never successfully replicated. Saxenian showed in Regional Advantage how even the Boston area failed and the fact that Paul Graham moved ycombinator fully out of Boston to SV is just another sign. In Europe, Sophia Antipolis was a first experience … in 1972 so? So you need a rare combination of ingredients in the recipe and hope the oven is at the right temperature for a long, long time. Now I am playing devil’s advocate so things are not so bad. As a positive reaction, let me add my own analysis: I am not sure governments are good at innovation, they are good at stimulating research. The US federal govt has put billions through DARPA, NIH, DOE, etc, and this obviously helped Stanford, Berkeley to be the best universities worldwide (see the rankings) and the Internet to be created. Long term investment in infrastructure is what gvts are good at (education, research, transport…) Then, yes, bridges with SV are critical. It is exactly how Israel, Taiwan, then India and China have been successful with their diasporas. Countries should invite back the experienced migrants. When he has time, Brin should help Russia or Levchin Ukraine, or even Grove Hungary etc… I am less sure tax credits, admin, legal tools have been so useful in the 50’s, 60’s and 70’s when SV was its in early days. As a conclusion, it is and will remain for a while a great topic.

Of course, my reaction was not as important as the source of the posts: Russia wants to be more innovative and commissioned a report to assess experiments of innovation ecosystems. The result is the following report: Yaroslavl Roadmap 10-15-20 (pdf format.)

There isn’t anything really new in this report, at least for innovation experts. But it is a very good synthesis of what the USA, Israel, Finland, India, and Taiwan have tried, be successful in, but also in what they failed. The historical summaries are great and full of good lessons. I had the feeling the authors put too much emphasis on infrastructure vs. culture. It is my own bias again! They mention culture a lot, but they may be aware also that it’s the most difficult thing to create… If you like the topic, you should certainly download and read the pdf, and build your own opinion.