“What Have VCs Really Done for Innovation?” This is the title of a post by Vivek Wadhwa dated September 20. You can find the full account on Techcrunch. I have to admit I was not happy with the content. Instead of saying immediatly why, I will let you read comments made by others as I shared their point of view. You can also read the post and all the comments, but they are numerous!

So, for example, I agreed with the following three comments:

by Ashok

It is true that the claims made by VCs are not realistic and vastly exaggerated. But, at the same time, we cannot forget that they have played key role in many innovative fields. By its very nature, a Venture Capitalist will invest only in a new promising project where he can hope to earn a handsome profit. There is nothing wrong in a VC selectively investing in projects. After all, we have to appreciate that for every one grand success, a VC may have seen 9 failures losing his money invested in projects which could not lead to big money. So, you have to judge the role of VCs also by their failed projects. Who would like to invest in a project which is likely to fail? Yet, it is a fact that a big percentage of projected financed by VCs fail. Does it not show the high risk involved in what VCs do? This being the position, what is wrong if they are selective in financing the projects? Therefore, the author’s observations “The fact is that VC’s follow innovation, they don’t lead. They go where they smell blood.” are not fully justified.

What about their failed projects? Did they not smell blood? Then why did they invest? Why did they fail then?

Unfortunately, the author has tried to present one-sided story without taking into consideration the problems which VCs might be facing.

Of course, at the cost of repetition, I would say that the tall claims made by the VCs are also not correct. To conclude, it is neither black nor white; it is some shade of grey. Truth lies somewhere in between the two extremes

then by Chris Yeh

This is one of the most dangerous and wrong-headed posts that I have read all year. And I’m flabbergasted by the lack of critical thinking displayed in the comments section.

There is definite truth to some of what Vivek has to say. The NVCA’s estimates are bogus, because they equate investing in a company with being responsible for its success. This is an egregiously egotistical assumption.

It may very well be true that the venture industry as a whole trails index investing. It’s hard to pick winners. But so does the entire actively managed mutual fund industry.

But the statement that “VCs at best have little to no impact on these companies and at worst have a negative impact” is absurd.

First, there is a major survivorship bias problem with the data. By interviewing successful companies, the study fails to prove whether VC makes success more or less likely. All it says is that the majority of successful new businesses in the US do not rely on VC.

A number of commentators seem to be of the impression that VCs make easy money by investing in companies after all the risk has been removed by the entrepreneur. This is talking out of both sides of one’s mouth. If the VCs aren’t taking risks, then how can they be delivering sub-par returns? By definition, they must be taking risks.

Venture capital plays an important role in the startup ecosystem. It provides high-risk equity capital to startup companies. Not every company can be a bootstrapped consumer Internet company. Many important businesses (semiconductors, hardware, biotech) require significant up-front capital. If VCs went away, would there be enough funding for these business? Do you seriously think banks would start lending to these companies?

I also wager that most of the commentators pooh-poohing VC would be glad to accept funding for their startups.

finally by ethanboss

… Of course there are VCs that don’t add value. As there are entrepreneurs who fail.: most of them. How ridiculous to claim that Sergey and Brin had already succeeded when KP and Sequoia invested. That shows a total lack of understanding of what it takes to build companies.

Also, I suppose capital would also grow on the trees for these “innovative” companies to go and harvest, so there is no need for VCs…

In the old days, when capital was hard to access there were some great entrepreneurs (few) that could get to profits without much help and capital. Some still do it but are the exception. The real world is a little different. You need capital and help with networks and other things to build a LARGE innovative company. Those things don’t grow on trees.

so here is the comment I made on September 25.

Vivek

I agree with many other people that you are too single-minded. I do not fully disagree with some elements of your analysis, which explains why you have so much support, BUT…

I was once a venture capitalist and I have neither an MBA nor a law degree but engineering degrees including a PhD and more importantly two years spent in Silicon Valley where I developed a passion for innovation and start-ups which I translated in becoming a VC.

One more fact in addition to the other contributions:

Surprisingly, Bill Gates had venture capitalists: this is taken from Microsoft IPO prospectus: “Mr. Marquardt has been a director of the Company since 1981. Since 1980, Mr. Marquardt has been a general partner of TVI Management. He has been with TVI Management since 1980. He is also a director of Archive Corporation and Sun Microsystems, Inc.” TVI had about 6% of Microsoft shares before the IPO.

Now what have VCs really done for innovation? You would have been more credible by saying what are they doing. But if you use the past, let me put some historical perspective:

– If investors (VC was not developed yet) had not funded Fairchild in 1957, Intel in 1968, Silicon Valley may not exist as it is. Your friend Vinod is maybe an exception, but there were many others. Arthur Rock helped in funding or funded directly Fairchild, Intel, Apple Computers.

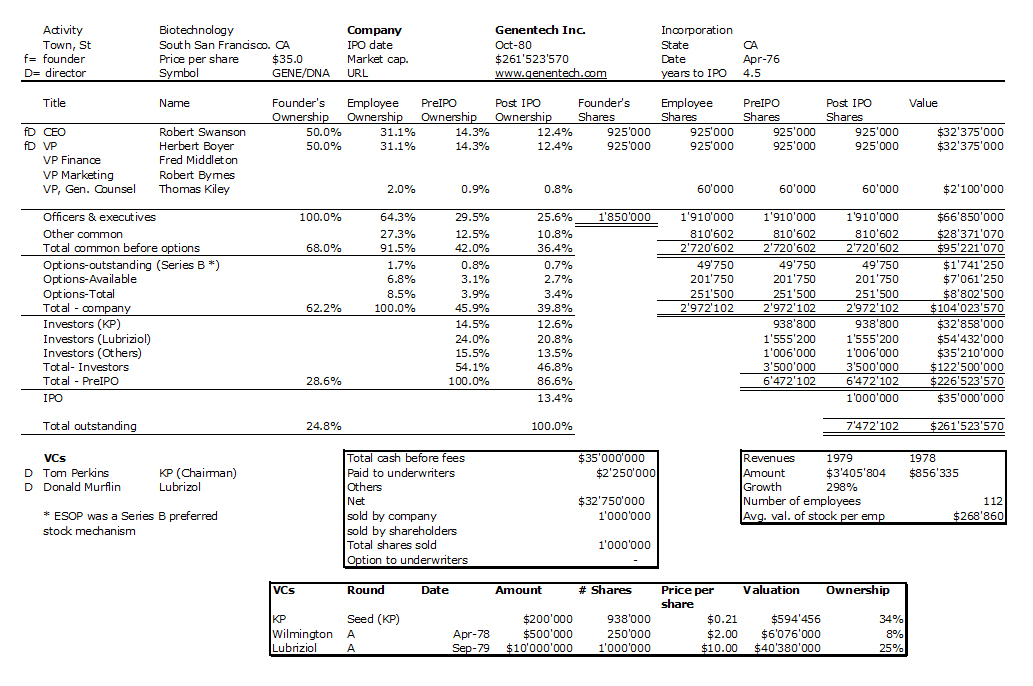

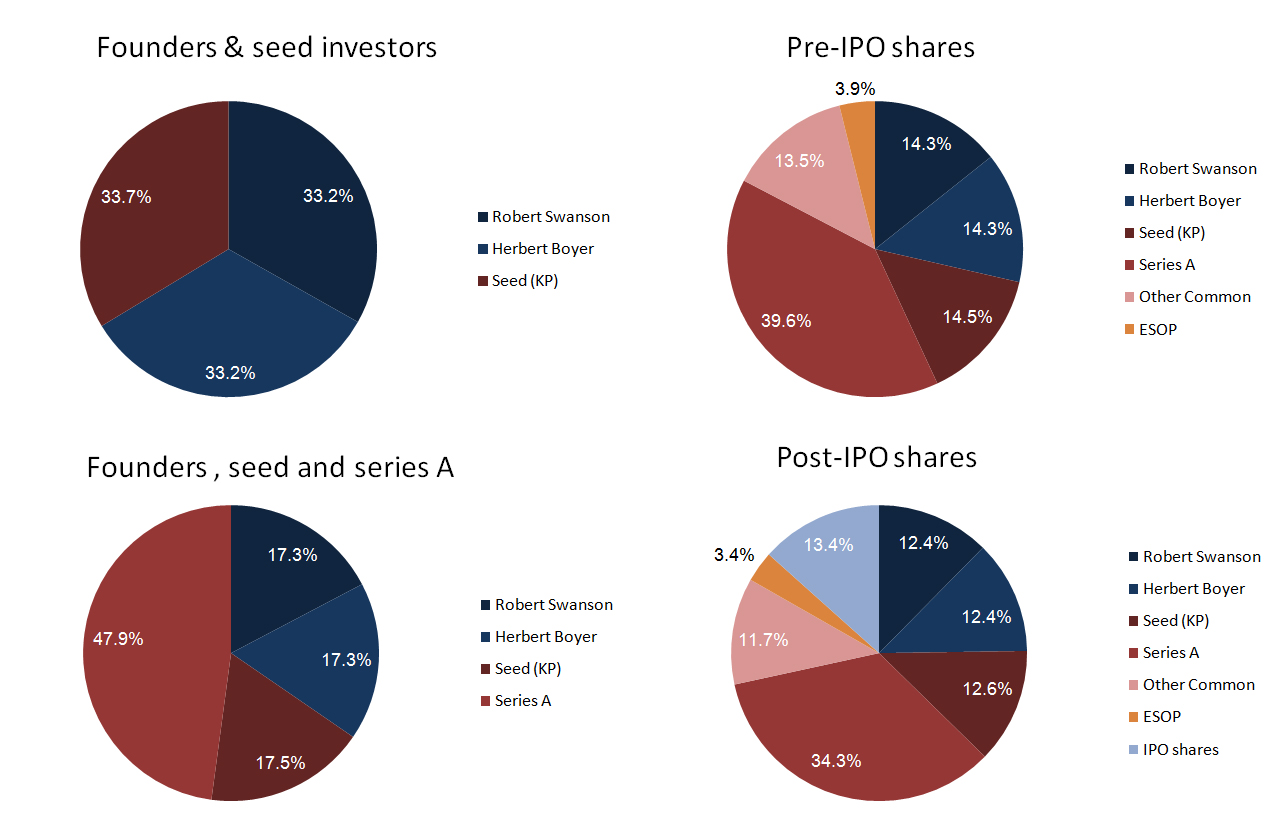

– The story of Genentech is well-known (go on my blog for more if you wish): when Bob Swanson, a former VC at KP became convinced biotech had a future, he first convinced Boyer, the researcher, then his former colleague Tom Perkins to try. Both were skeptical, so you are right Entrepreneurs are in the driving seat, but without the inventor and the investor, Genentech and then the biotech industry may not have existed. The innovation did not exist yet and the VCs contributed a lot.

– Who do you think were the first VCs such as Gene Kleiner and Don Valentine and many others? They were former entrepreneurs who had the vision that funding the next generation would fuel innovation.

I am also doing an analysis of startups created with Stanford technology or by Stanford Alumini. The surprising fact is that so far about 30% of the companies (I have a total of 2’700) were funded by VCs. It does not mean VCs were responsible for their success, but they had their contribution (in the group are companies such as Cisco, Yahoo, eBay, Google, Rambus, Atheros and so many others)

Paul Graham says that for innovation, you just need nerds and rich people. I agree with him. The nerd is the brain and the investor is the blood. And then both will need a team, managers, employees which will constitute the full body. VCs do not contribute to inventions, but they help in their commercialization, which is I think the definition of innovation.

You are not only singled minded but I think you are hurting the innovation ecosystem. I see too many entrepreneurs and future entrepreneurs scared with investors because they focus on your point of view. Of course, there have been terrible stories. But do not forget entrepreneurs need resources to succeed. Repeat entrepreneurs may bypass investors, business angels may help when resources are not too huge (maybe like in software though this is not even always true). But what about young people who develop semiconductors, biotechnologies, green technologies and have no money.

Money is never cheap or fun. But you need it. Let me finish with two quotes which show that I support some of your views but I still disagree with your overall vision.

In the book Founders at Work, one entrepreneur says about investors: “You can’t live with them, you can’t live without them” and even better Robert Noyce, Intel’s founders: “Look around who the heroes are. They aren’t lawyers, nor are they even so much the financiers. They’re the guys who start companies”

cheers

Herve