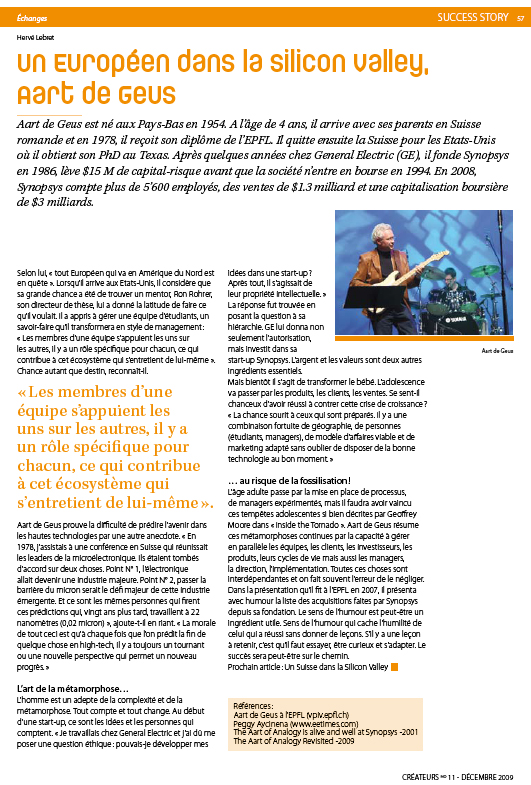

Here is my fourth contribution to Créateurs, the Geneva newsletter, where I have been asked to write short articles about famous success stories. After women and high-tech entrepreneurship, Adobe and Genentech, here is Aart de Geus, founder of Synopsys.

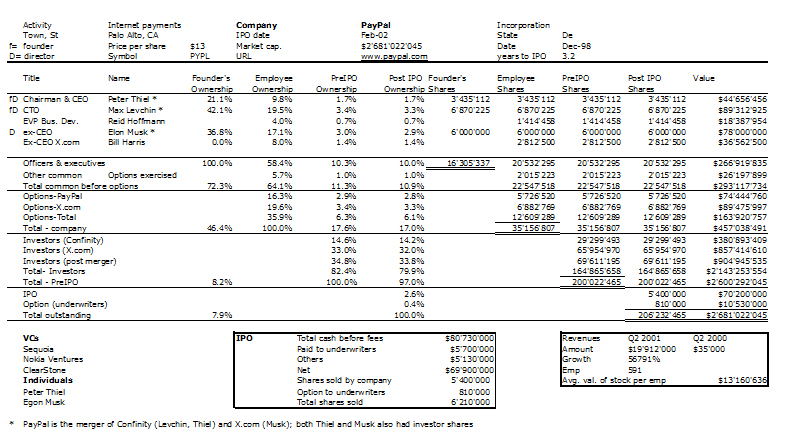

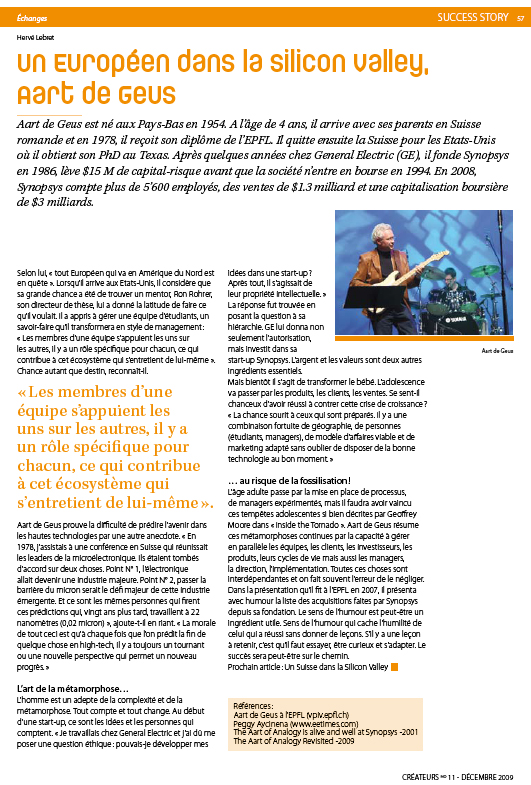

Aart de Geus was born in the Netherlands in 1954. At the age of 4, he moved with his parents to french-speaking Switzerland and in 1978, he graduated from EPFL, the Swiss Institute of technology in Lausanne (where I currently work). He then moved again to the USA and got his PhD from the Southern Methodist University in Texas. After a few years with General Electric (GE), he founded Synopsys in 1986, raised $15M of venture-capital before Synopsys went public (in 1994). In 2008, Synopsys had 5’600 employees, $1.3B in sales and a $3B market capilalization.

According to him, « Everybody from Europe who comes to the U.S. or Canada is looking to discover something ». In his case, when he arrived to the USA, he was lucky in being assigned as a graduate student to Ron Rohrer “He took a liking to me. […] Rohrer essentially gave me the freedom to do whatever I wanted within the graduate school research facilities”. Rohrer became his mentor. He learnt how to manage a team, a know-how he changed in a management style. “everybody counts on the team and there’s always a role for everybody, which produces an ecosystem that manages itself.” He recognizes it is as much luck as destiny.

He also shows how difficult it is to predict anything: “In fact, I’ll tell you a story. In 1978 or ‘79, I attended a conference in Switzerland of leaders in the field of electronics, or microelectronics. They all agreed on 2 things. Number 1, electronics was going to be a big deal and would move forward for many years to come. Number 2, one micron was the hardest barrier that we would never move across. And [laughing again], those same people who made the predictions are the ones who made 22 nanometers happen!” and he adds: “The lesson here: whenever one predicts the end of something in high tech, there’s always a twist or new perspective that makes a new breakthrough possible.”

Aart de Geus, a born entrepreneur?

The art of metamorphosis…

Aart appreciates complexity and metamorphosis. Everything is important and everything changes. In the early days of a start-up, ideas and people matter. When you have an idea, what do you do? “First, you write a business plan. Then, you ask, is it ethical? Is it okay to do that? How do you go about planning the business so as not to go up against GE?” Well, according to Aart, “there’s a simple answer. You write a business plan and propose it to GE. After all, it was clearly their IP. Period.” GE not only backed the idea but invested in it. Money and values are essential at that stage.

But the baby has to grow. The teenager will have to develop the products, sell them to customers. This may be a tough crisis. Does Aart feel lucky to have survived? “Luck favors the well prepared,” and added that a fortuitous combination of management, graduate students, geographic location, viable business plan, and marketing expertise were augmented by having the “right technology at the right time.”

Back to EFPL in 2007.

… with the risk of becoming a dinosaur !

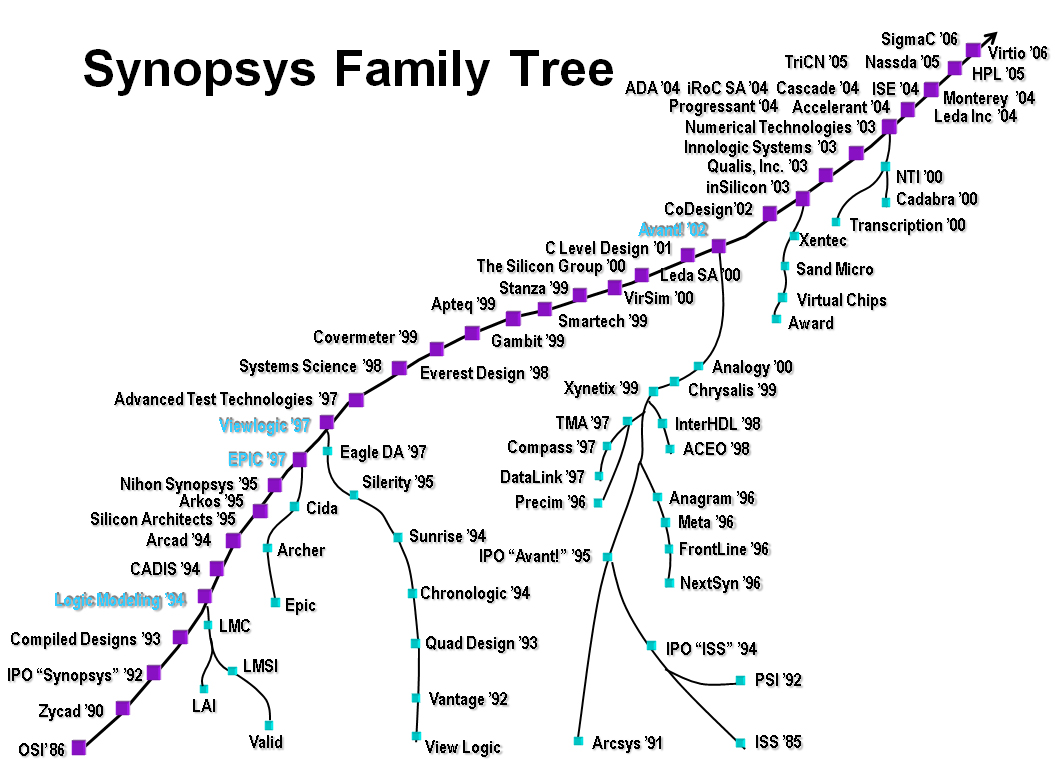

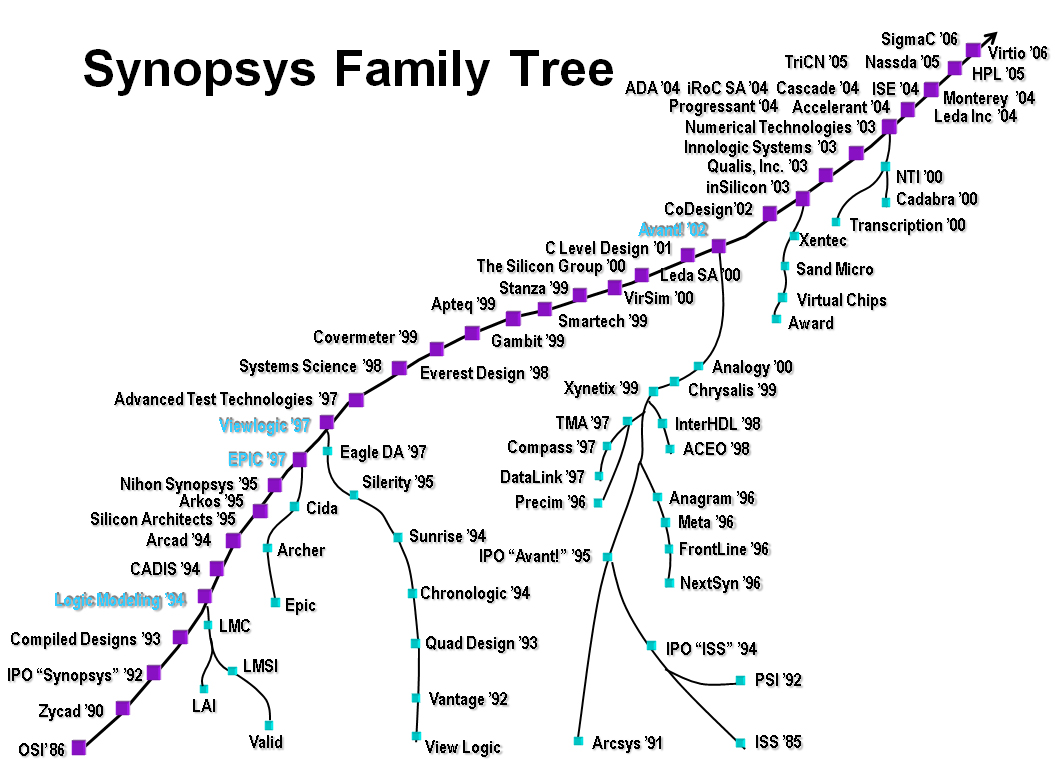

The adult age means processes, experienced managers so you need to survive the tornadoes that Geoffrey Moore describes so well. Aart summarizes these permanent metamorphoses through a parallel management of teams, customers, investors, products and their cycles, but also managers, leaders, implementation. All these things are interdependant and it is often underestimated. In a talk he gave to EPFL in 2007, he showed the history of Synopsys acquisitions in the form of the animal below! His sense of humour was certainly very useful. This sense of humour hides the humbleness of the individual who succeeded without giving any lesson. If there is one lesson in all this, is that you must try, be curious and flexible. Success may come.

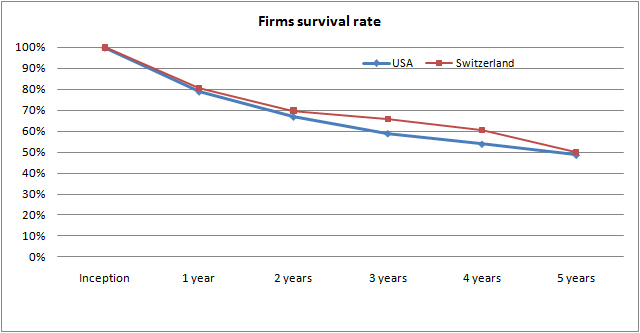

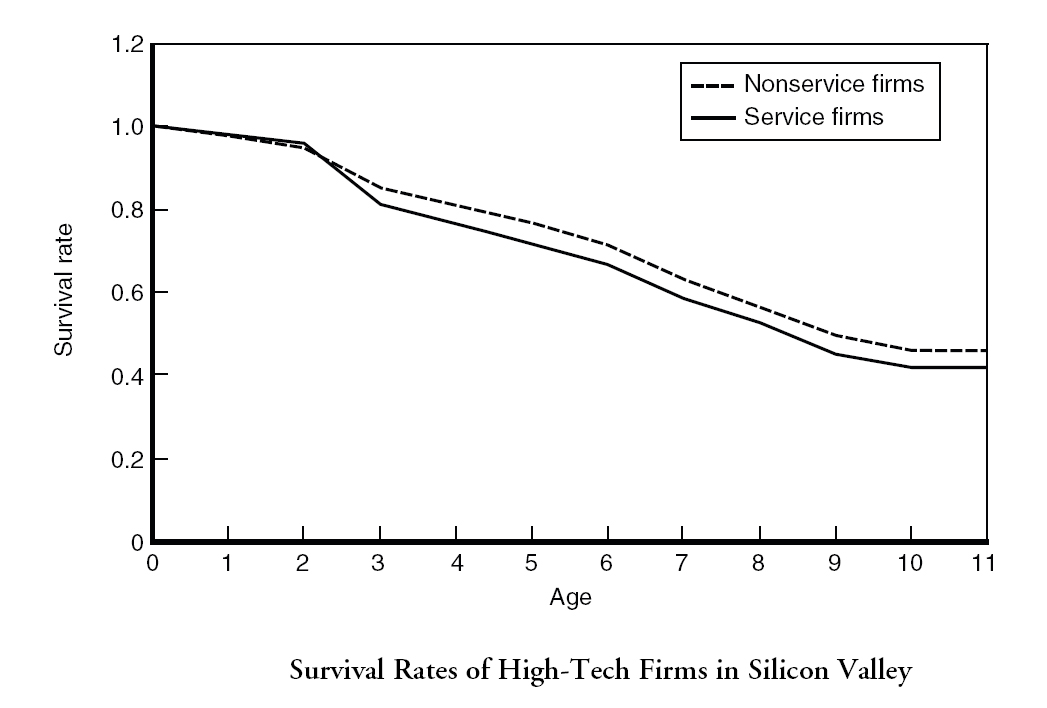

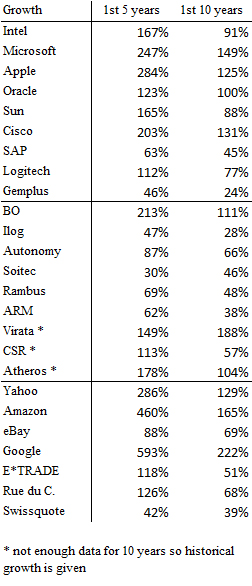

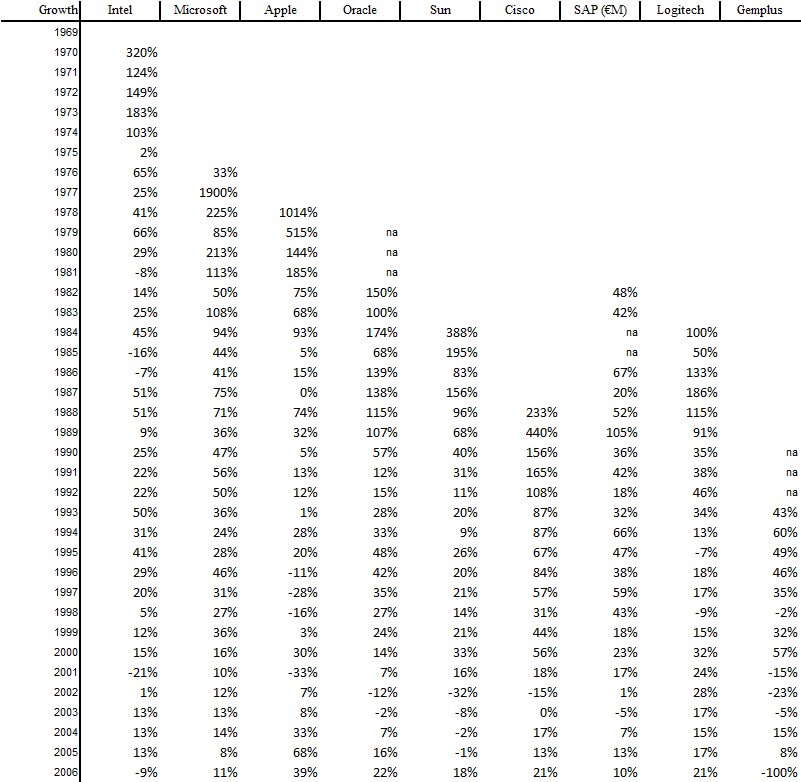

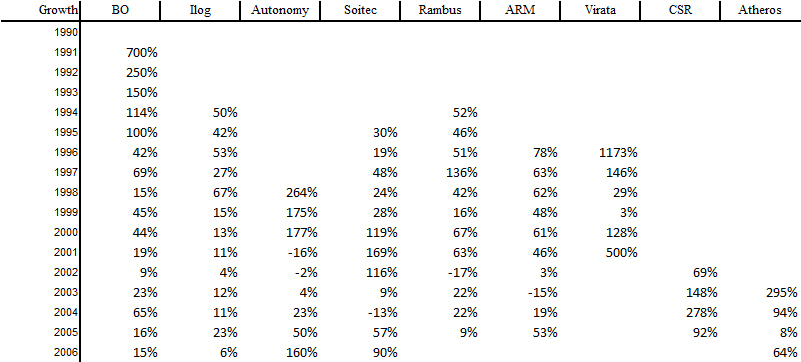

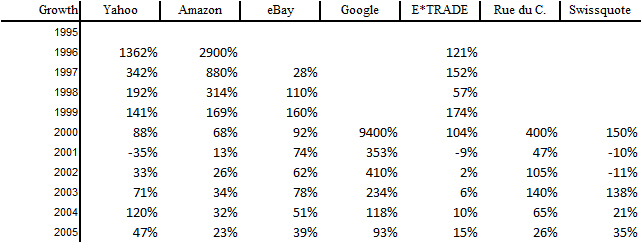

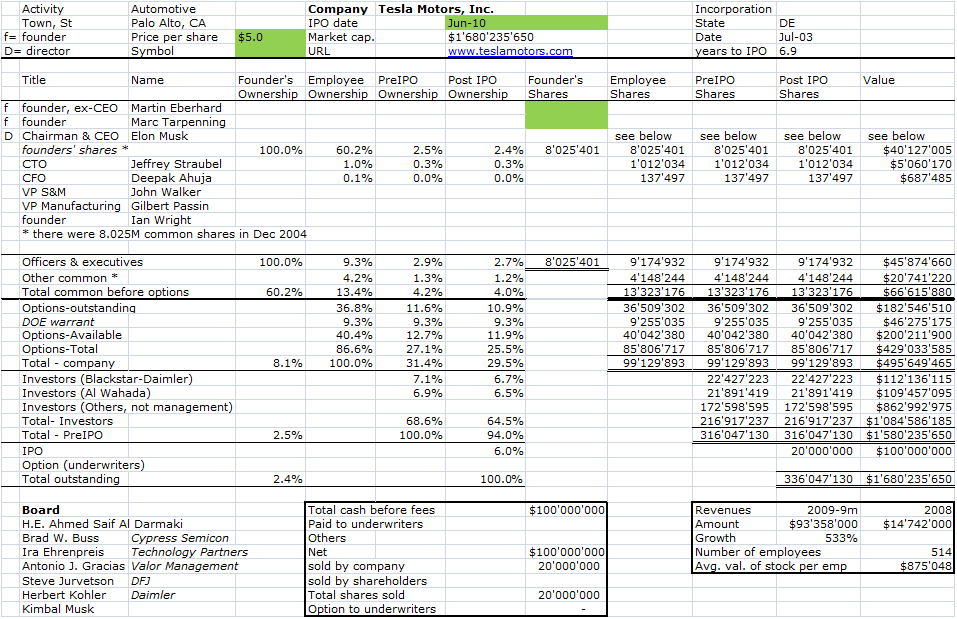

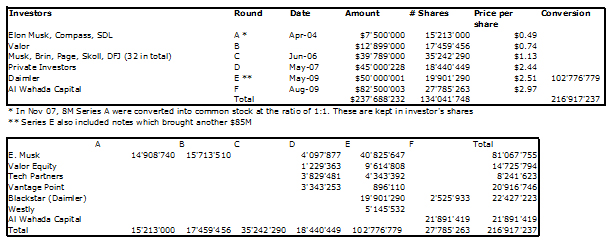

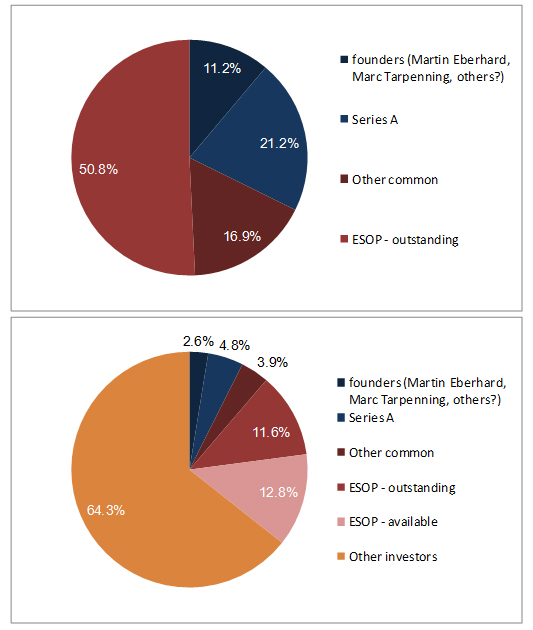

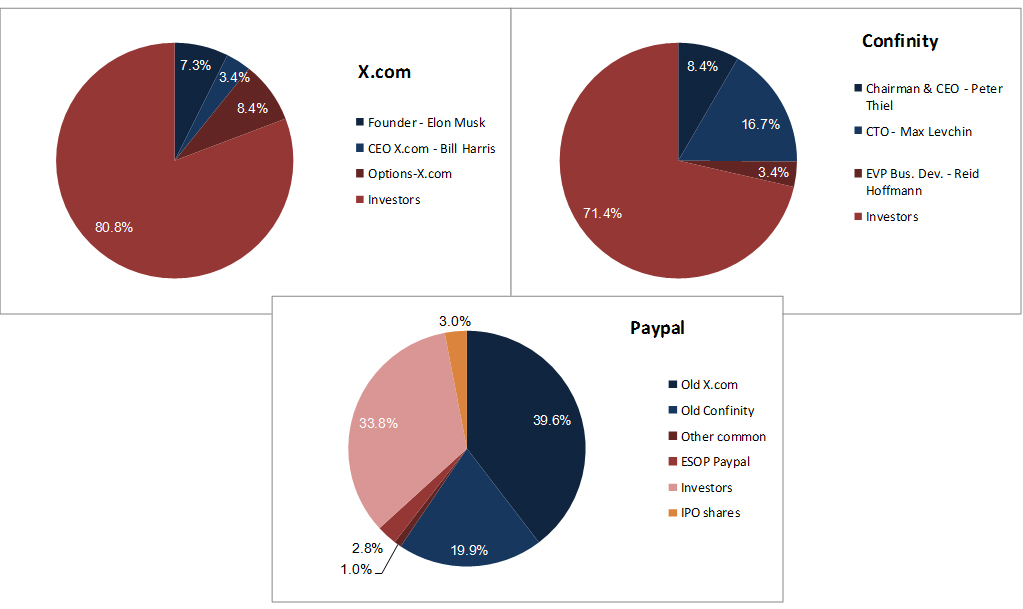

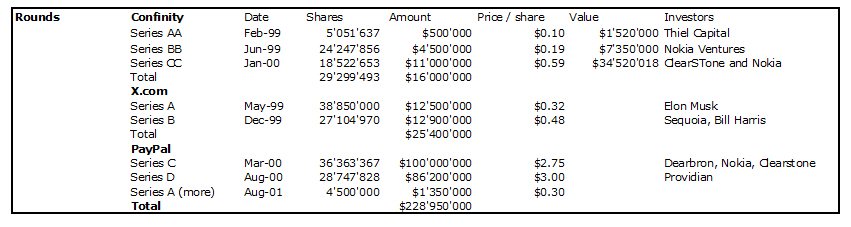

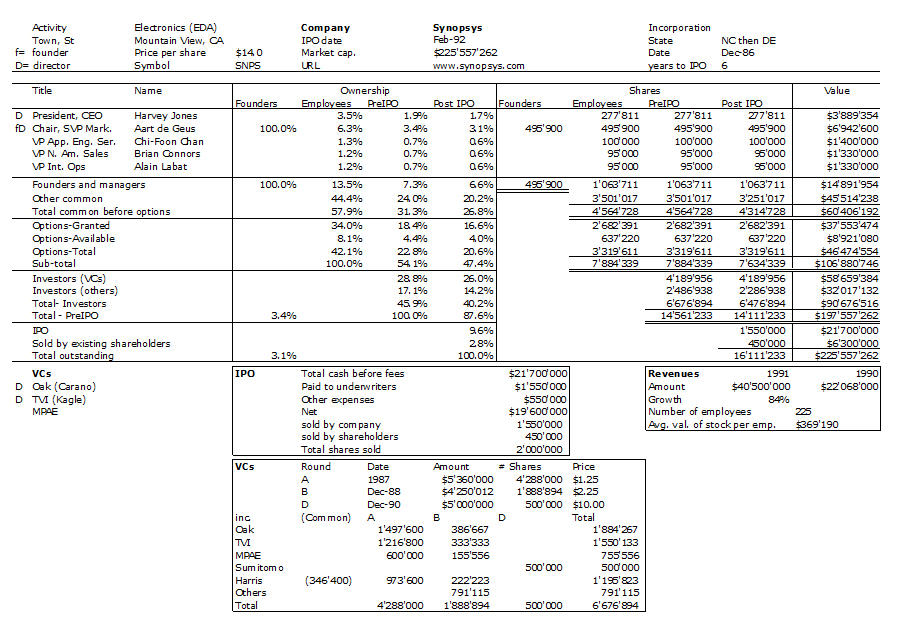

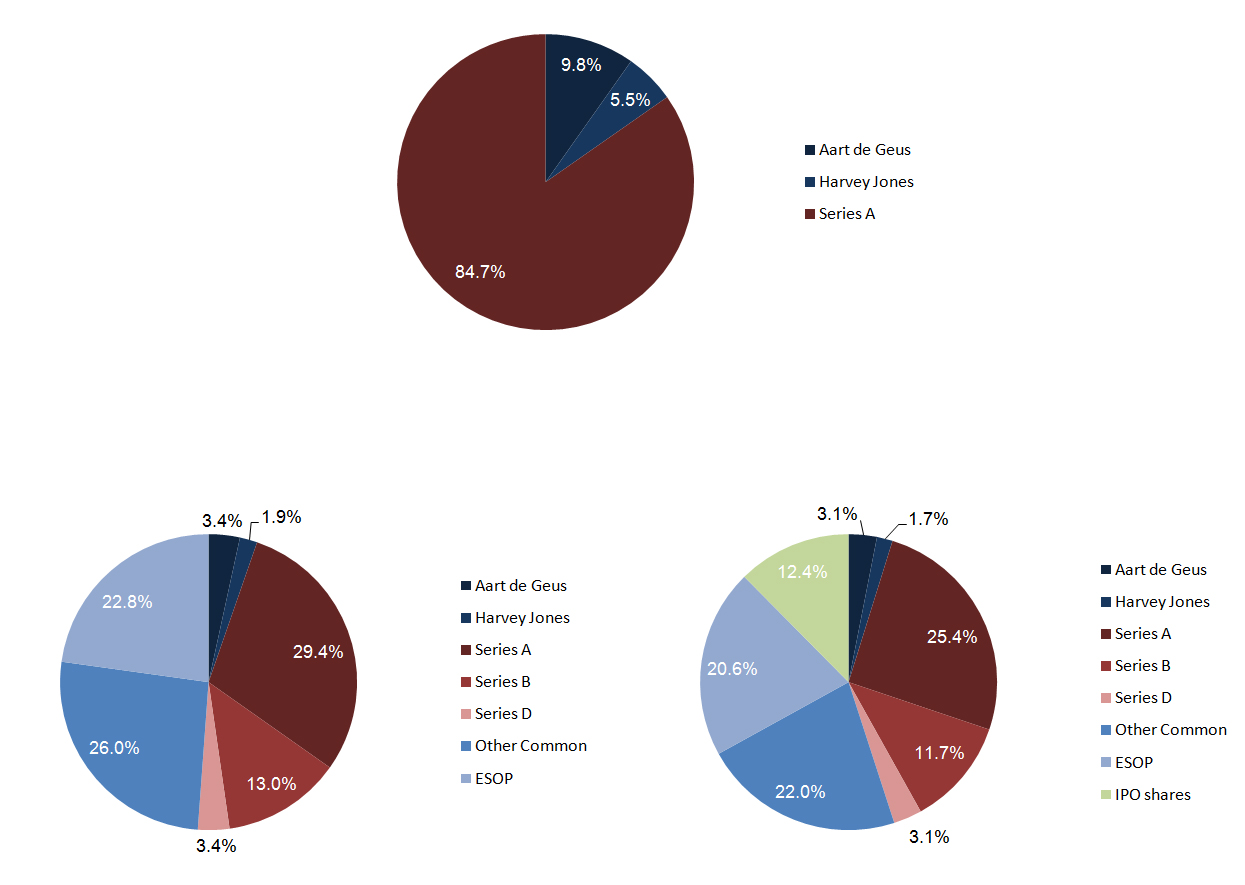

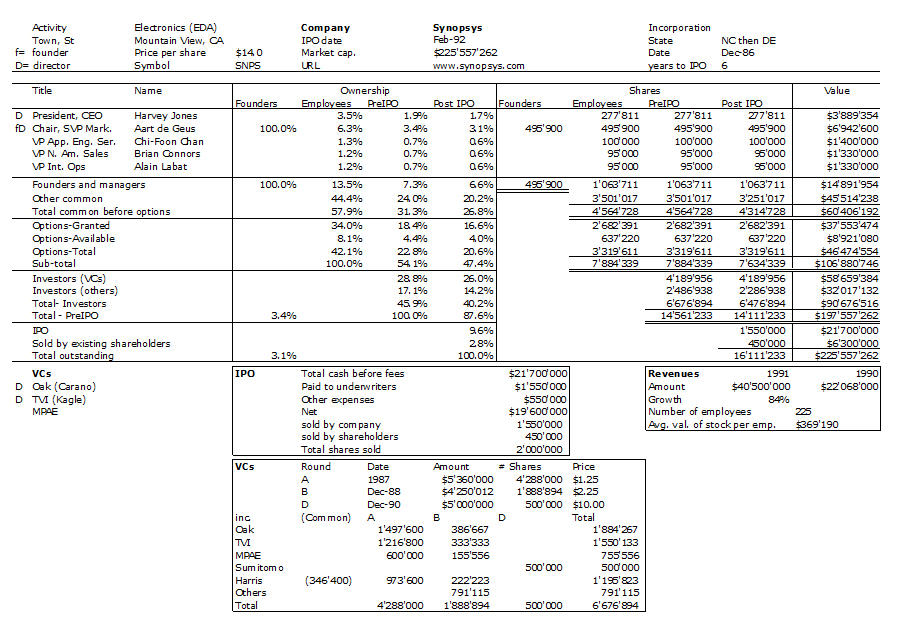

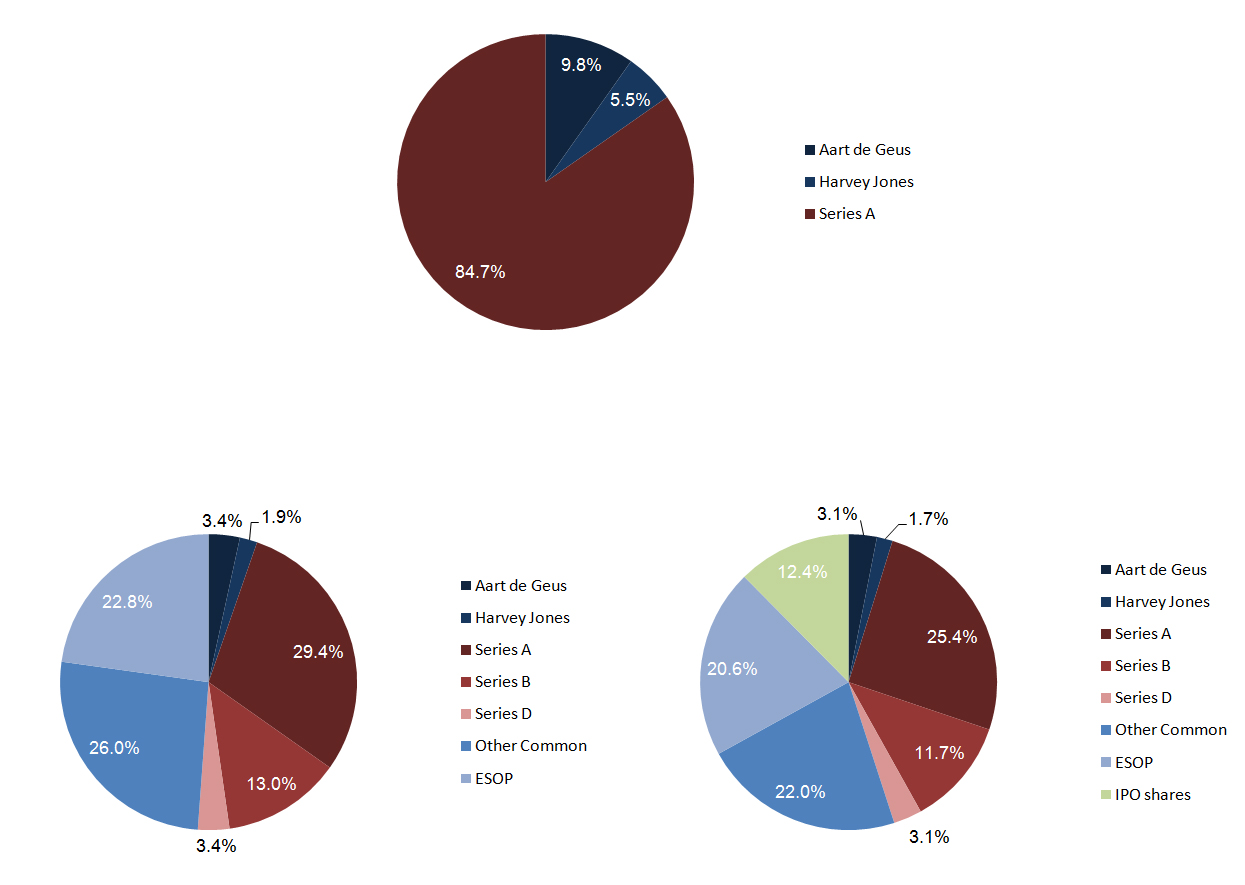

As usual, I finish with my beloved capitalization table and charts.

Sources :

-Aart de Geus at l’EPFL (vpiv.epfl.ch)

-Peggy Aycinena (www.eetimes.com)

The Aart of Analogy is alive and well at Synopsys -2001

The Aart of Analogy Revisited -2009

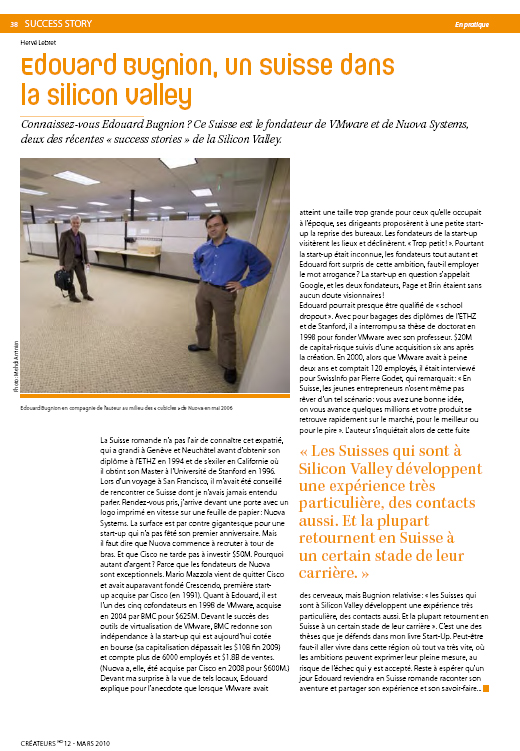

Next article: A Swiss in Silicon Valley