A new report has been published about the Entrepreneurial Impact of MIT

It is full of data and even if obviously self-serving, it remains very interesting. Let me just quote what I noticed:

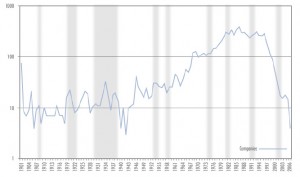

– Growth: the number of “first-time” firms has increased from about 2’000 in the 70s to 6’000 in the 80s and 10’000 in the 90s.

– Origin: Non-US founders had slight visibility in the 40s, grow to 12% in the 90s and 17% in the 00s. 30% of MIT foreign students founded a company at some point.

– Age: Before and during the 70s, 24% of first-time entrepreneurs were under 30, growing to 31% in the 80s and 36% in the 90s. There is no real difference between industry segments.

– Serial entrepreneurs: I have a small disagreement on that point as I am not sure serial matters, but… about 40% are serial entrepreneurs so 60% are not…

– Engineering vs. business degrees: EE/CS degrees is 22%, management is 16% for the 90s. Clearly science and technology matter.

– Location: in the 50s and 60s, majority of companies were in Massachusetts, but thereafter Silicon Valley has become a critical locus. In the 00s, 26% are in MA and 22% in CA.

Then the report talks about the culture and the ecosystem. It is also very interesting. We should always remember that:

– Tons of money went to research from the militaries and space agencies.

– MIT had more of a tacit and hands-off role, but much encouraging.

– Role models: “entrepreneurs could name about ten other new companies before they started their own”. Authors compare to another study where “Few of the Swedish entrepreneurs could name even one or two others like them”. They quote Schumpeter: “The greater the number of people who have already successfully founded new businesses, the less difficult it becomes to act as an entrepreneur. It is a matter of experience that successes in this sphere, as in all others, draw an ever-increasing number of people in their wake”

– Feedback loop: there is a positive impact of such examples and this may be the main reason of the creation to tech. clusters.

– Culture: the best is a quote by Bob Metcalfe, Ethernet inventor, founder of 3Com and now a partner at Polaris Ventures: “It’s not just that MIT’s entrepreneurial environment flourishes under its institutional commitment to technology transfer,” he said. “It’s also that MIT includes both ‘nerds’ and ‘suits.’ Divergent life forms, yes, but necessary to and working together at MIT on entrepreneurial innovation. And what keeps MIT’s entrepreneurial ecosystem accelerating is that nobody is in charge. There are at least twenty groups at MIT competing to be the group on entrepreneurship. All of them are winning.”

… Nobody is in charge…

– Tech. transfer: the majority of the exclusive licenses go to startup companies. The TLO’s strategic dependence on startup companies has been the reluctance of large companies to invest in “university-stage” technologies, because the risk and cost of development is high and the time to market is long.

– License deals: For startups, instead of cash up front and in lieu of some of the royalties, the TLO usually takes a small equity ownership that is less than 5 percent of the new firm.

And some conclusions:

– Universities that are strong in research and technology are at the forefront of knowledge creation and potential application. When the university is able to couple this capability with the inclination and resources needed to connect ideas and markets, impressive possibilities exist for generating entrepreneurship-based economic impact at the local, as well as national and global levels.

– Numerous changes are needed in most universities over an extended period of time in rules, regulations and, more important, attitudes and institutional culture.

– Until quite recently, MIT had followed a “hands-off” approach toward entrepreneurial engagement, in contrast with many other universities in the United States and abroad. MIT has neither created an internal incubator for ventures nor a venture capital fund to make life easier for prospective startups.

– Instead, MIT has relied internally on growing faculty, student, and alumni initiatives, especially during the most recent thirty years, to build a vibrant ecosystem that helps foster formation and growth of new and young companies.

– Educational programs require investment in and acquisition of faculty to develop and teach such programs. Effective and well-trained academics are, unfortunately, still scarce in most entrepreneurship related disciplines. Fortunately, successful practitioners are available everyplace and the MIT history indicates that they are quite willing and enthusiastic about sharing their time and experiences with novice and would-be entrepreneurs.

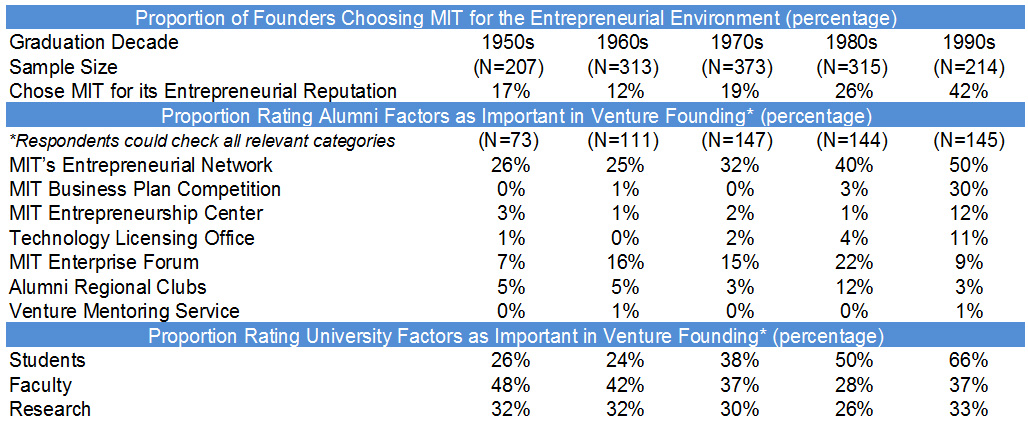

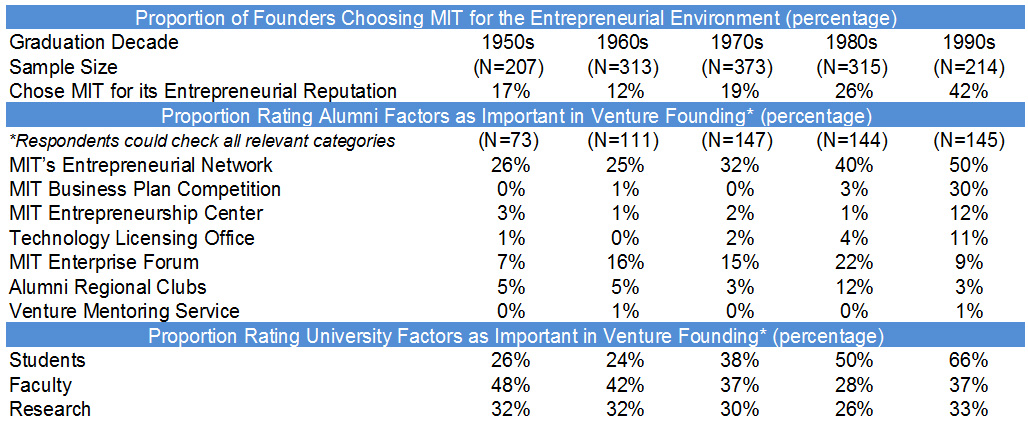

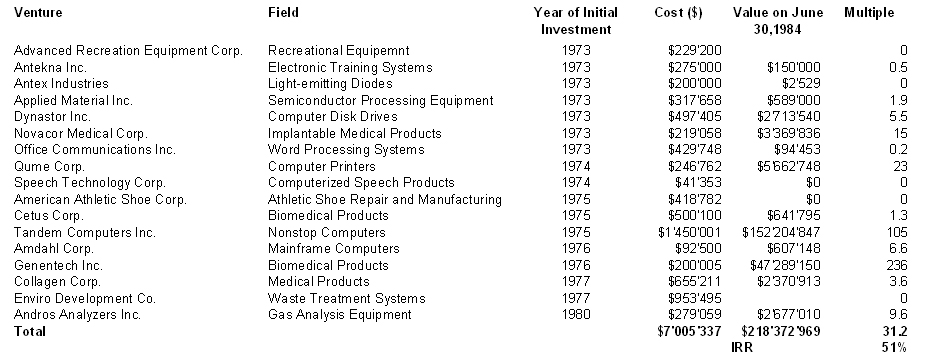

For those who have been so far, first you should read the full report and second I aggregate below a few tables from the report: