This is the title of a great article from the not less great New Yorker, dated November 23, 2020 and written by Charles Duhigg:

How Venture Capitalists Are Deforming Capitalism,

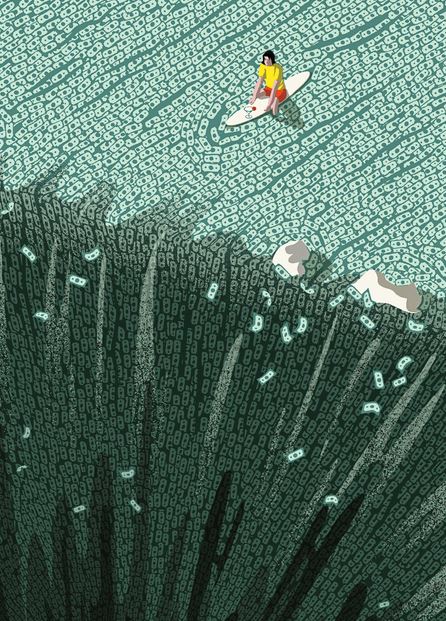

Even the worst-run startup can beat competitors if investors prop it up. The V.C. firm Benchmark helped enable WeWork to make one wild mistake after another—hoping that its gamble would pay off before disaster struck.

Illustration by Golden Cosmos (from the New Yorker article)

I am infringing copyright here and hope the magazine and author will forgive me. But the illustration says so well what the author describes! Yes, for a few years now, venture capital has become a crazy money spending machine.

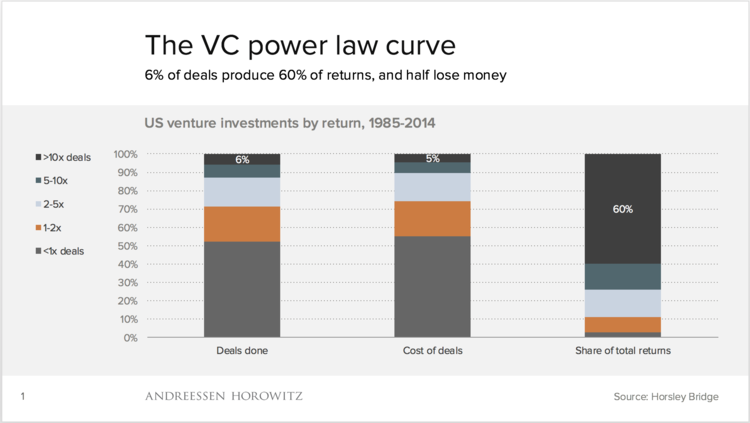

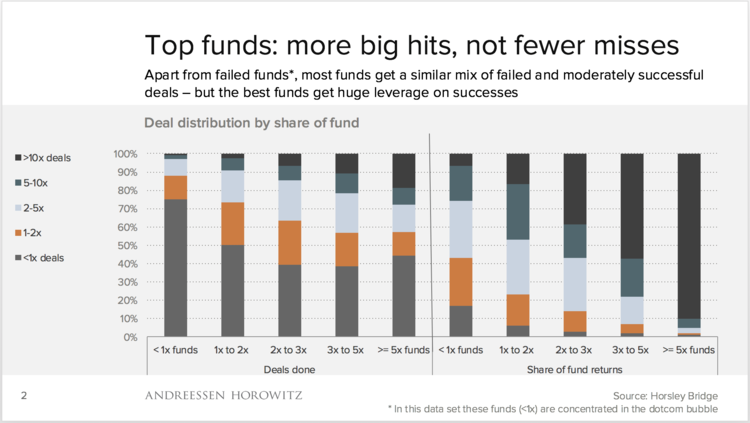

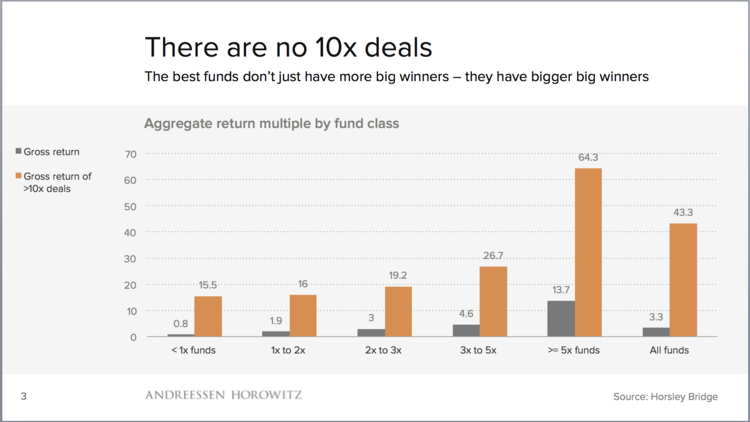

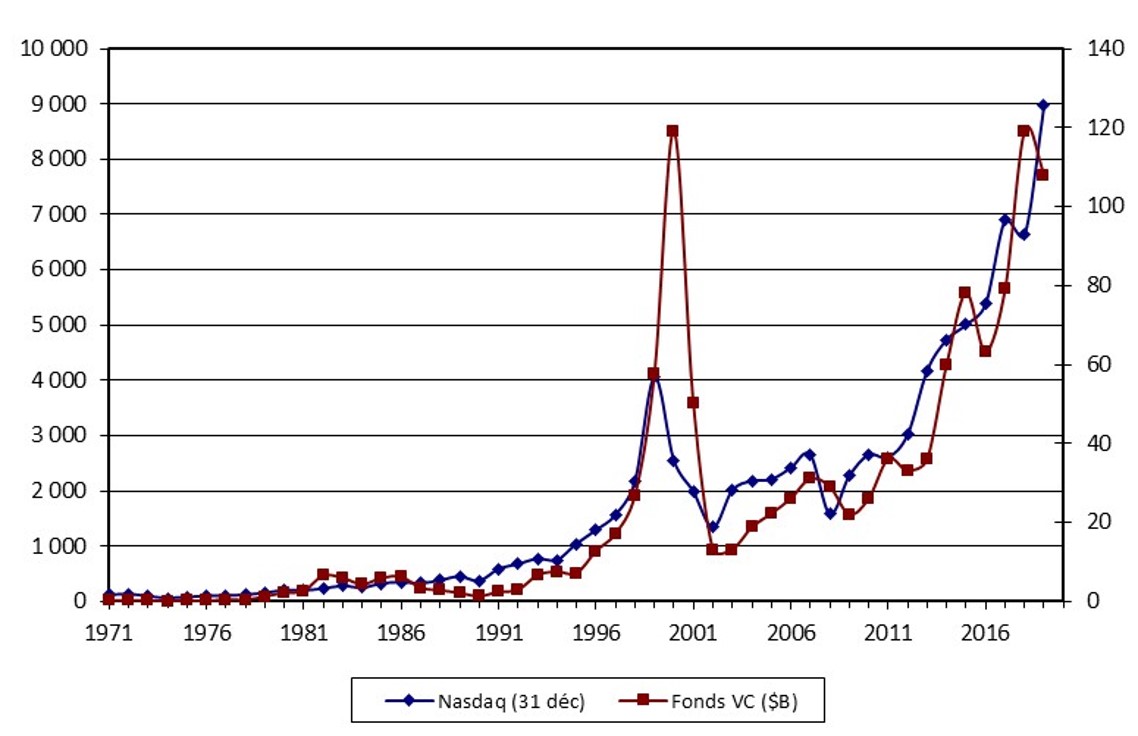

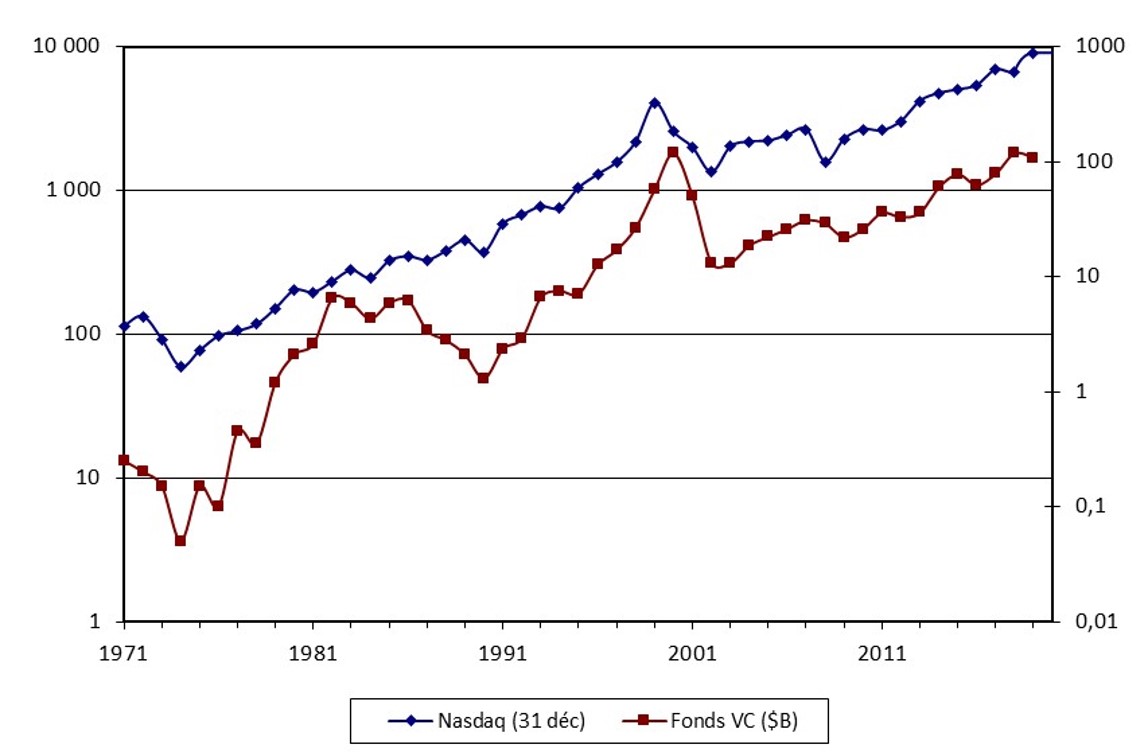

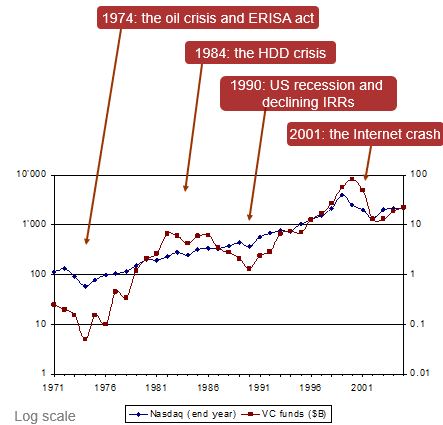

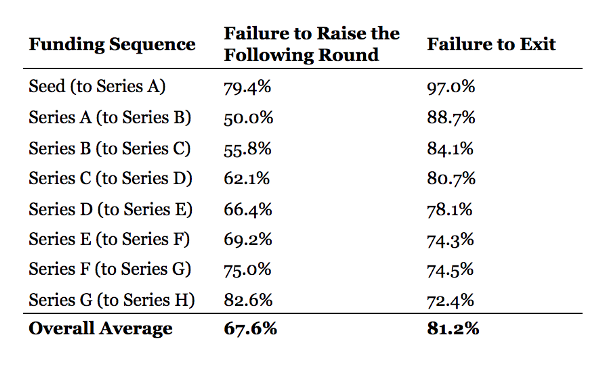

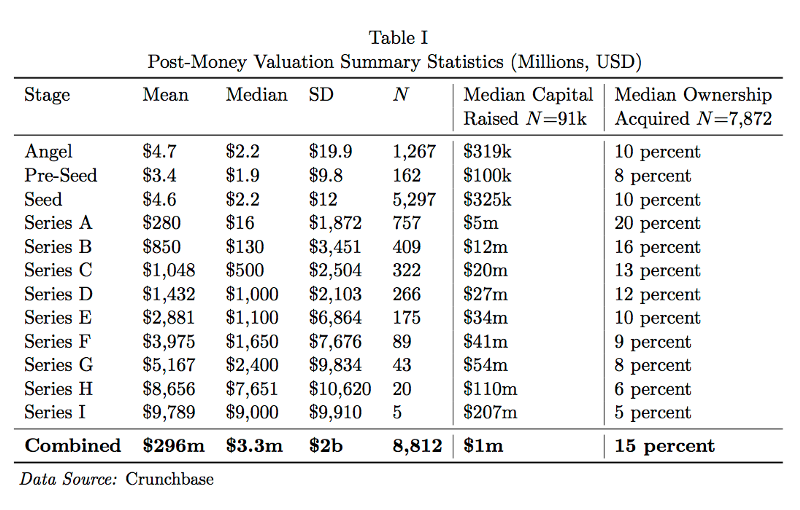

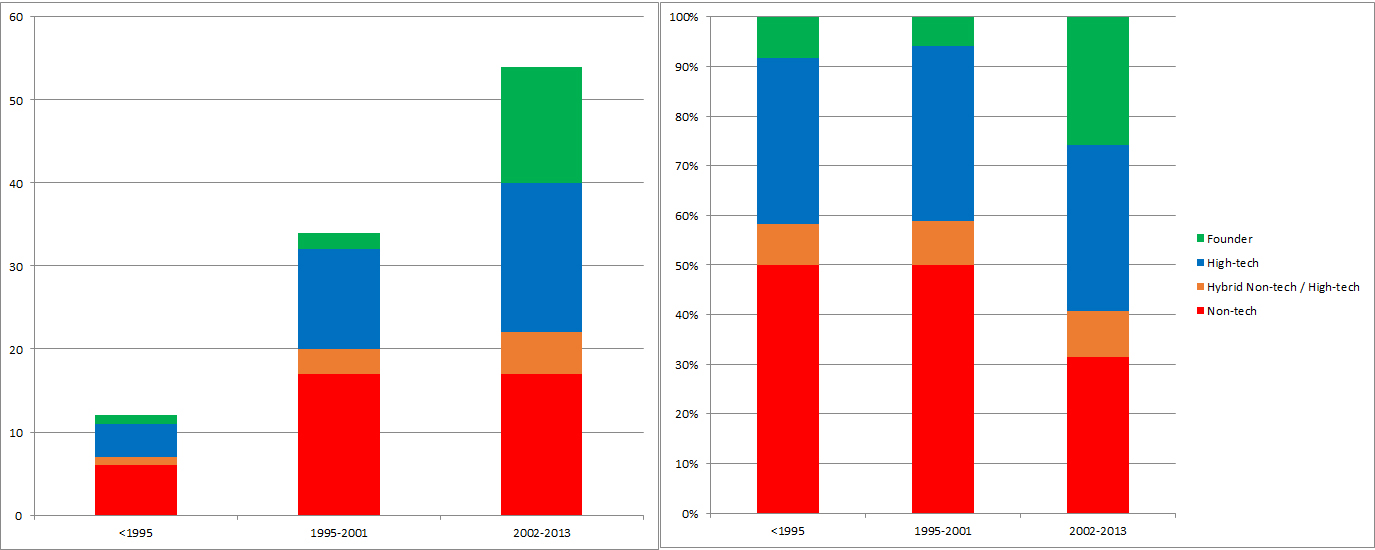

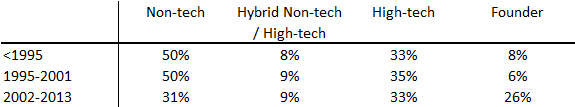

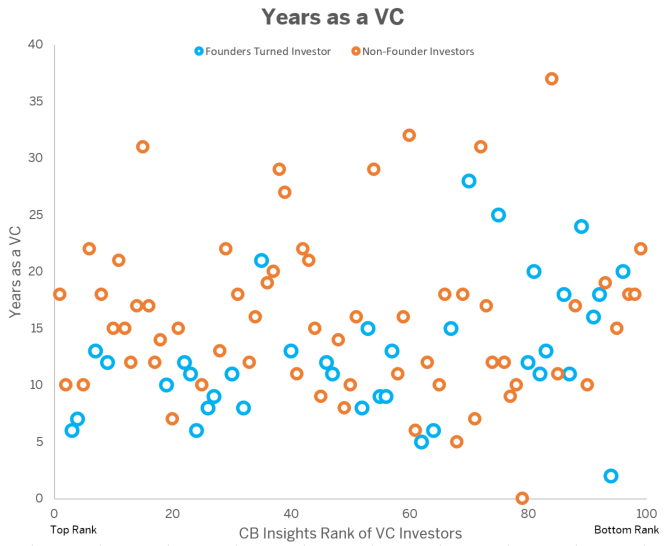

I already posted blog about VC crises as over time the activity as evolved. From frugal investors in technology in the 60s and particularly in the 70s (Apple, Microsoft,..) and 80s (Cisco, Sun, …) The internet “bubble” was not the first period of hubris, there was one in the early eighties with tons of PC clones. But the real hubris came with the social media. Today, startups raise hundreds of millions of dollars before going public and experience huge, huge losses even at IPO as you may want to check in my 600 startups analysis (and it will be probably even worse in my 700 startups analysis to come). Here are past articles:

September 2020: Theranos, the (not so)-Silicon Valley biggest scandal ever – https://www.startup-book.com/2020/09/12/theranos-the-not-so-silicon-valley-biggest-scandal-ever/

April 2016: Is the Venture Capital model broken? – https://www.startup-book.com/2016/04/26/is-the-venture-capital-model-broken/

January 2016: Is Silicon Valley crazy (again)? – https://www.startup-book.com/2016/01/28/is-silicon-valley-crazy-again/

January 2011: Is there something rotten in the kingdom of VC? –

https://www.startup-book.com/2011/01/27/is-there-something-rotten-in-the-kingdom-of-vc/

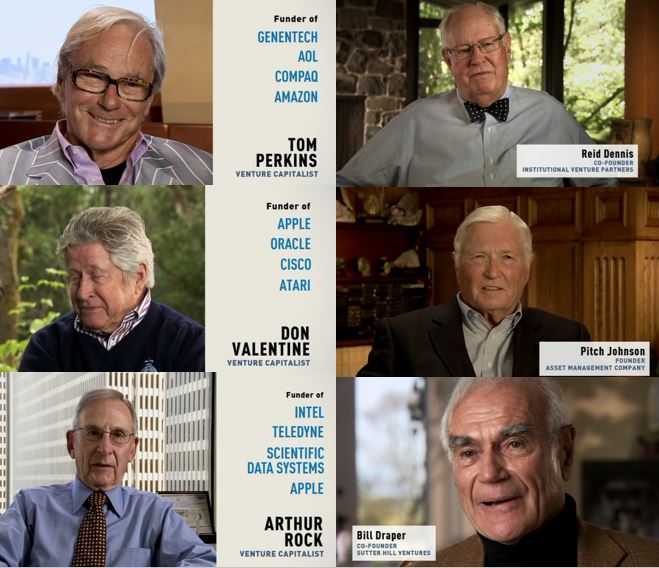

At this point read carefully what venture capital was according to the author of the article: From the start, venture capitalists have presented their profession as an elevated calling. They weren’t mere speculators—they were midwives to innovation. The first V.C. firms were designed to make money by identifying and supporting the most brilliant startup ideas, providing the funds and the strategic advice that daring entrepreneurs needed in order to prosper. For decades, such boasts were merited. Genentech, which helped invent synthetic insulin, in the nineteen-seventies, succeeded in large part because of the stewardship of the venture capitalist Tom Perkins, whose company, Kleiner Perkins, made an initial hundred-thousand-dollar investment. Perkins demanded a seat on Genentech’s board of directors, and then began spending one afternoon a week in the startup’s offices, scrutinizing spending reports and browbeating inexperienced executives. In subsequent years, Kleiner Perkins nurtured such tech startups as Amazon, Google, Sun Microsystems, and Compaq. When Perkins died, in 2016, at the age of eighty-four, an obituary in the Financial Times remembered him as “part of a new movement in finance that saw investors roll up their sleeves and play an active role in management.”

But some famous experts of innovation are quoted about the current situation:

Steve Blank: “I’ve watched the industry become a money-hungry mob. V.C.s today aren’t interested in the public good. They’re not interested in anything except optimizing their own profits and chasing the herd, and so they waste billions of dollars that could have gone to innovation that actually helps people.” and his answer to the crisis is quite strong: “The first time you see a venture capitalist prosecuted for failing to uphold their duty as a board member, you’re going to see Silicon Valley transform overnight. All it takes is one V.C. doing a perp walk and everyone gets the message—you’re responsible, you have a legal duty, and if you do things that are bad for society you’ll be called to account.”

Martin Kenney, the professor at the University of California, Davis, said, “Obama loved Silicon Valley and V.C.s, and Trump craved their approval.” He went on, “Regulators have been totally defanged from doing real investigations of venture-capital firms. I think people are finally waking up to the damage the tech industry and V.C.s can do, but it’s slow going.” Today’s V.C.s, “money-losing firms can continue operating and undercutting incumbents for far longer than previously.”

Josh Lerner, a professor at Harvard Business School: “Proclaiming founder loyalty is kind of expected now.”

A Harvard Business School professor, Nori Gerardo Lietz, noted that the document exposed WeWork’s “byzantine corporate structure, the continuing projected losses, the plethora of conflicts, the complete absence of any substantive corporate governance, and the uncommon ‘New Age’ parlance,” the S-1 was “misleading, and probably fraudulent.”

I will finish my post with a quote mentioned by Bruce Dunlevie, the partner from Benchmark who was one the WeWork boardmember, a task he did not handled perfectly even if not that badly. Nothing to add. “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” Lord Acton and the rest of the quote (not mentioned in the article) is “Great men are almost always bad men…”