I was interviewed last Thursday by Martin Würmseher, a PhD student at ETHZ working on the concept of Founding Angels [0]. “Founding Angels help bridge the so-called gap, which exists between academic research and the commercialisation of the new technologies. Together with inventors, they found start-up companies to further develop the research and commercialise the results. The Founding Angels business model is similar to that of Business Angels, but the operational and financial support of Founding Angels begins before the actual founding of the start-up and, as a member of the founding/management team, continues in the founding and building up of the new start-up company.”

Martin sent me yesterday the transcript of the interview and I liked it very much. Martin authorized me to publish it so here it is!

Interview: 16.01.2014, 11:00-11:45, Skype Call

WM: OK let’s start with your professional activities at the Technology Transfer Office for EPFL – if you can just describe your activities? #00:00:16-6#

HLE: OK, so I am not at the Technology Transfer Office, I am the Vice President for Innovation and TechTransfer. The TTO, the Technology Transfer Office, is one of the units and they manage patent applications, licenses or also research contracts. I am managing another unit called “The Innogrants“, which is also part of the same Vice-Presidency and I am also supporting entrepreneurs. I can give them grants for one year, similar to the PioneerGrants at ETH Zurich that Professor Siegwart I think put in place. Innogrants also organizes conferences called “Venture Ideas” with Venture Lab where I invite entrepreneurs. And I try to support entrepreneurs in ANY [!] manner which they need. #00:01:01-9#

And for your information, before being at EPFL, I was in venture capital with IndexVentures in Geneva. So I have been in the start-up world for many, many years. And before being at IndexVentures I was a researcher in applied mathematics. So my background is technologies and venture capital and now I support entrepreneurs. #00:01:21-7#

WM: OK, so for how many years did you work for a venture capital firm? #00:01:23-5#

HLE: Six years, from 1997 to 2003, and I have been with EPFL since 2004. #00:01:31-2#

WM: OK, then it’s a quite senior position now… and experienced person. #00:01:39-1#

HLE: “Senior” I’m not sure but “experienced” for sure! #00:01:41-5#

WM: In which stage do the people come to you? #00:01:51-8#

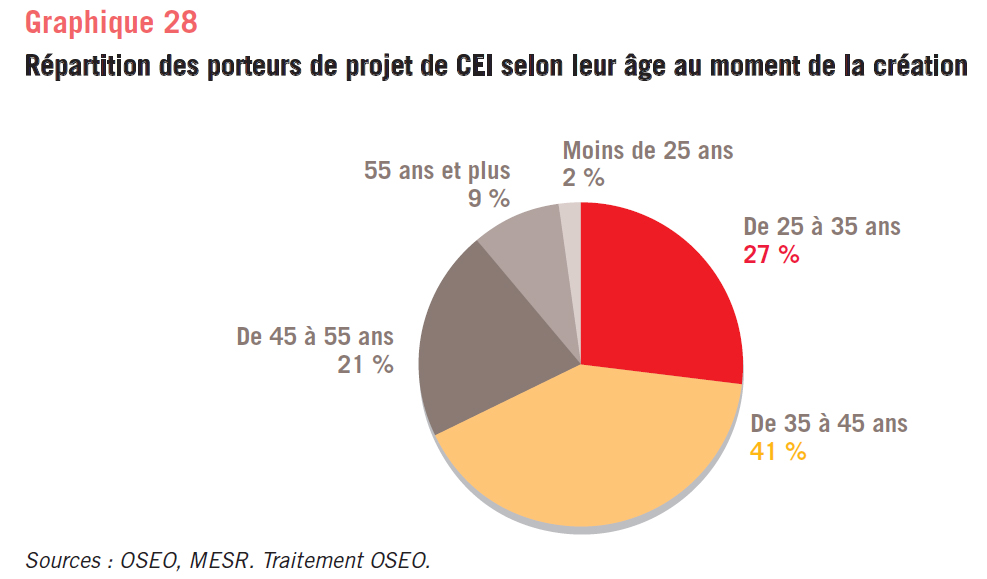

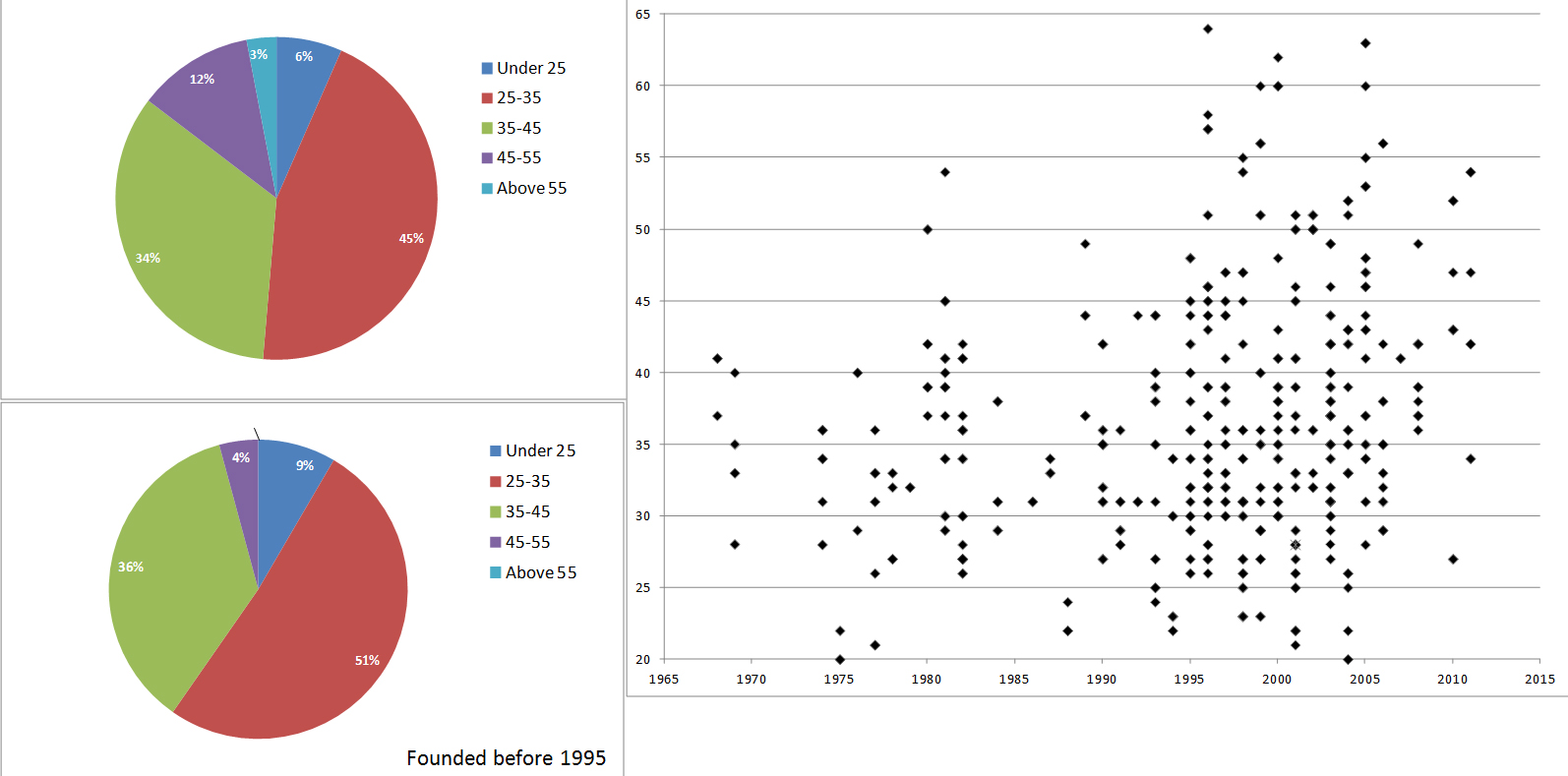

HLE: Usually they come because they have an idea and they most often come when they are finishing their Ph.D. and they are thinking: “Maybe I have something that COULD [!] have a commercial interest, I would like to work on the idea.” So I give them the opportunity to work on that idea for ONE [!] year, an Innogrant is a one year salary, but it’s open to any students at EPFL. So a Bachelor or Master student could come and I could fund them, too. And I can even fund people outside from EPFL, coming with an idea and then they would be employed at EPFL for a year. But it’s mostly Ph.D. students, statistically it’s for 80% Ph.D. students and then maybe 10% engineers from the outside with an idea – in terms of the people I fund. #00:02:39-8#

WM: But from all academic fields or are you just focused on Life Science or….? #00:02:46-5#

HLE: No, all technology fields. #00:02:48-6#

WM: And how many people are there coming [to you] per year? #00:02:52-2#

HLE: So in fact, so if you are interested in the details… – but there is a page on the Innogrants and there are documents that you can download – but basically I have about 60-70 people coming to me and I give about 5 to 10 grants – eight; 10 Grants in the good years, 5 grants in the poor years. #00:03:17-1#

WM: My primary focus is on spin-off / start-up companies: How many start-up companies are emerging from EPFL per year? #00:03:27-1#

HLE: So EPFL creates about… -usually said- one start-up per month, so it’s about 12-15 start-ups per year. In the good year it were 20 in the bad year it were 5. Again these numbers you could find on the same document I was mentioning. In fact I am always comparing with ETH Zurich, which always has about twice the number of start-ups we have, they have about 20-24, we are more in the range of 12-15. #00:03:55-2#

WM: Can you please send me the link to the document. #00:04:00-2#

HLE: Yeah, in fact I will send you the link to both, the webpage of the Innogrants and then the PDF-document. […] [sending; see eMails] [..] #00:05:16-3#

WM: And what are in your eyes the main challenges of the young people to create their own start-up company? #00:05:26-9#

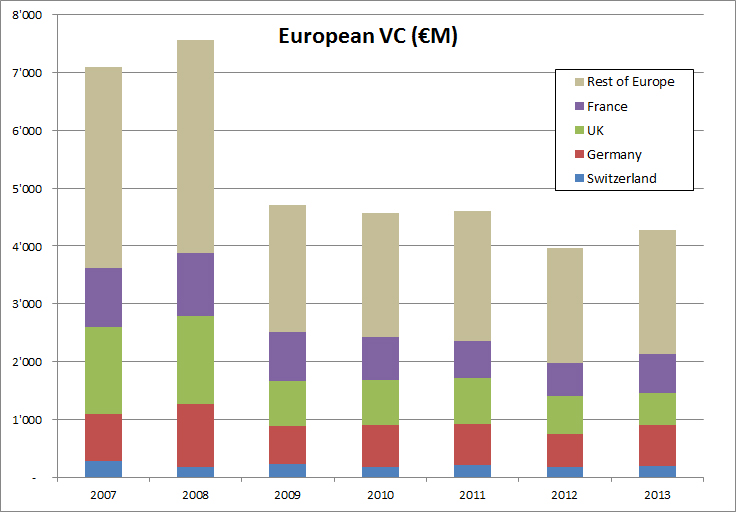

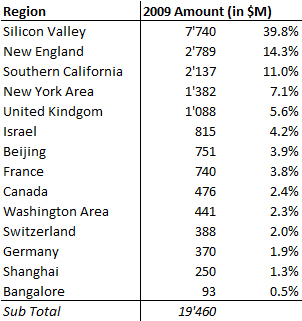

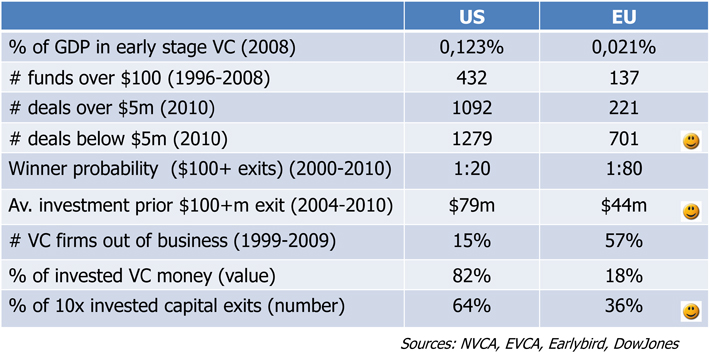

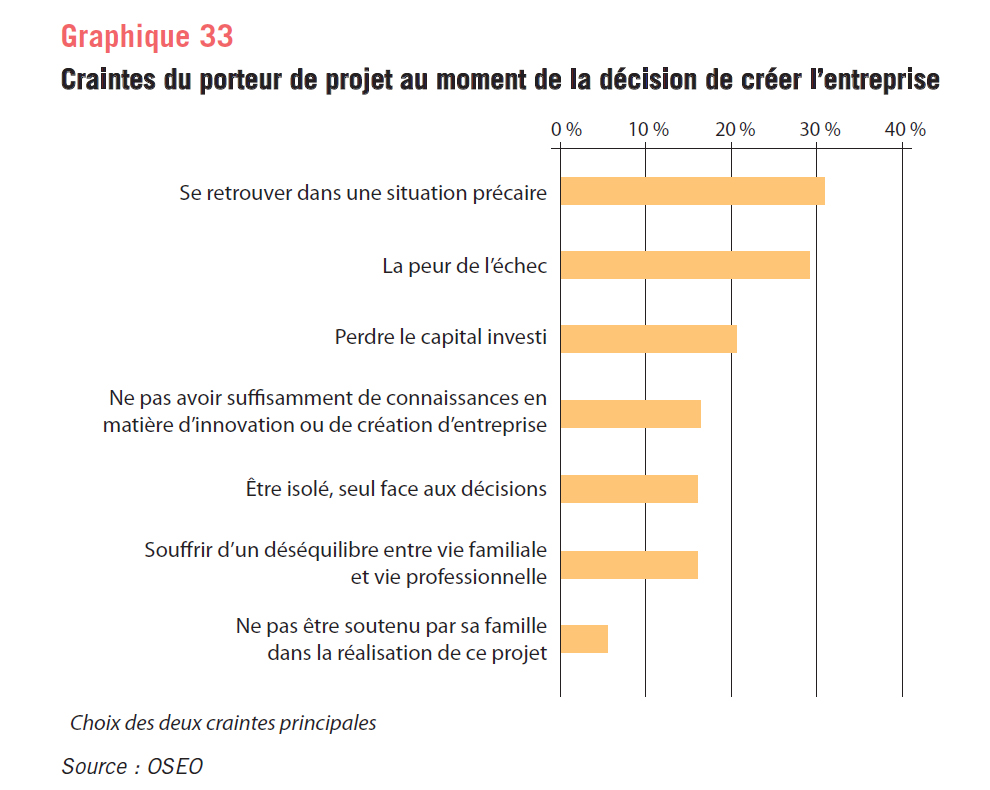

HLE: So there are many, many challenges. Let’s try… I wrote a book on start-ups in 2007 and I have a blog, which is called “Start-up book” and you can have a link about it. In fact, yesterday I put on my blog a very long article about the reasons why European start-ups’ failures compared to the American ones. OK, I think the MAIN [!] challenges, the MAIN [!] challenges and people are not aware of that is the fact that in Europe we don’t have an entrepreneurial culture. The culture in the US or in Israel is so developed, it’s much easier for a young guy with no experience to develop something just because he has around him people who know how to do it. So the main challenge is a) about culture… – and we can have debates, but that’s my point. Then there are two more, let’s say, tangible challenges, which is the lack of experience and the lack of financial resources. People don’t know how to build a company because they don’t have the business or just poor product development expertise. So they need to be surrounded with people who can help them because there are maybe GREAT [!] ideas, but no experience and they lack the financial resources. So what is missing is really: Talent and Money. #00:07:12-4#

That’s what I would say: So first culture, then the amount of money. And when I’m saying “culture”, you know the fear of failing, the risk-taking mentality which is… all these elements. But I can send you this in writing if you want. But then it’s really talent and money. #00:07:29-6#

WM: OK, that was exactly the next question: what do you understand by “culture”? But… #00:07:37-7#

HLE: Well let me send you the link to the article I wrote, in fact I wrote it, to be honest, in 2012… – never published it because it was a kind of working document with a colleague and finally I published it yesterday, so it was a kind of accident. And then you will see what I mean by “culture”, so the 2nd eMail that you will receive in a few seconds [see eMail]. But it would be a very long discussion about culture. But it’s really what I called: “Fear of failing”, “Risk taking attitude”, which is basically: it’s better working for Credit Suisse or ABB or Nestlé because you can have a solid career versus going to a start-up where your parents and your friends will tell you: “Are you crazy??! This is really a bad choice to making your life!” Whereas in Silicon Valley, I studied there for 2 years, most of the engineers are thinking: “Well should I do a start-up first because if I don’t do it now, then I will never do it?!!” So it’s what I called “culture”. #00:09:04-8#

WM: OK, I think I understand it. And with regard to the Professors: Are they usually involved or they pushing, or what is their…? #00:09:14-4#

HLE: Well it depends: It’s very interesting, there is one Professor who is very friendly with start-ups and in his lab, there have been 13 start-ups which have been created. Thirteen… – well it’s probably now 15 but I think it was 13 last year and among them you have very successful ones. His name is Philippe Renaud [1] , it’s in micro technologies and he is very friendly with entrepreneurs. There are also Professors, they just don’t care, it’s not that they are against, but they don’t care. They are focused on their academic career, publishing papers, teaching… – and they don’t think that’s in their mission to to do technology transfer or innovation, so they don’t care. I think it’s a pity, but it’s a free world and people should do what they love. There are cases where I have the feeling that people are even AGAINST [!] start-ups, saying that it’s a harder way to create innovation and they should do it with SMEs, small companies, or established companies. But I don’t think this happens often. #00:10:18-4#

WM: Do you think the Professor is decisive for this attitude or…? #00:10:31-6#

HLE: It’s a good question. When I was studying at Stanford University, all the Professors… -well most of the Professors I had were saying: “If you have a great idea, maybe you should think about creating a start-up…” So it’s, again we are going back to “culture”: So the Professors can be inspirational, so they can have a high impact just because they are encouraging. Whereas if the Professor is just neutral, then the students don’t know what it is about and then the impact is zero. Then if you are talking more concretely about the help, yes they do, because when I was over there, most of the Professors were founders of the start-ups, they would never quit their academic position, they were sometimes chief scientists or they were advisors in the Board. Some of them were even taking a one year sabbatical because they were passionate about the idea and I know many of them who have done that. And of course when a Stanford Professor or a famous Professor is in a start-up, when you go to investors it gives much more credibility or weight because investors have the feeling that you have a strong technical background, whereas students who are alone may have less credibility. So the Professors would never be the managers or never be full-time in a company, but they can still have an impact in terms of credibility. #00:11:55-6#

WM: And in your are in Lausanne how are they usually involved? Are they shareholders or are they just in an advisory position? #00:12:06-1#

HLE: I don’t have the details but I can give you the example of two companies like Kandou or Typesafe , where the Professors were in fact the early CEOs of the companies, so they have taken a one year sabbatical and they are extremely active and hands-on. And I see other cases where the Professors are board members, are small shareholders, advisors. Philippe Renaud is careful because he is helping all his start-ups, he doesn’t have the time to be a board member on all these companies, but he is an advisor for most of them even if it is informal. And I would claim that… -I’m not sure- but most of the Professors are [co-]founders and shareholders of the start-ups. Yes! #00:12:49-2#

that’s another strategy: they are not managers. #00:12:57-4#

WM: And who is preparing the businessplan of those start-up companies then? Is it….? #00:13:01-8#

HLE: Now I will tell you something that my colleagues at ETH would be shocked about because I know that… certainly Silvio Bonaccio and Matthias Hölling at ETH Transfer… and from what I understand to be an ETH Spin-off, you need to provide a businessplan. When I was in venture capital I was always saying, and I’m saying that to all my students and entrepreneurs, I don’t care about businessplans! The best companies ever never had a businessplan, so businessplans are not important. Of course it’s important for the entrepreneur because it’s a document which helps him to structure his own project. But in terms of the business value of the businessplan, it is nearly zero. So as a venture capitalist I never read a businessplan, I am reading the first page of a businessplan and then I say: “Whow this is interesting…!” Then I go quickly to the team and I say why it is interesting. I put an eye on the numbers, I never believe in the numbers because they cannot be right, they are either too optimistic or pessimistic but they are never right, so I don’t care. So we were just asking for a meeting and in the meeting with them if there was something we liked, we made our own Due Dilligence because you cannot base your decision just on what the entrepreneurs say. And then you decide whether to invest or not. #00:14:23-6#

So who is writing the businessplan?! The entrepreneur, he has to write it and usually it’s a young student… – but again: I’m not sure whether the businessplan is an important element. What is important is: Do these people have the drive to go to potential customers to understand if there is a business [market]. It’s a debate. Of course you need a businessplan, the investors will always ask you for a businessplan, but I think what is important is: Do they have an idea which has some potential and which is credibile? And then they can convince investors by talking to them. [hesitating 3 seconds] #00:15:03-5#

It’s a long debate… #00:15:03-5#

WM: And regarding the financing: Who is responsible for this and when are the Venture Capitalists… ? #00:15:12-5#

HLE: There has to be an entrepreneur right??! The entrepreneur might be a student, might sometimes be the Professor but it’s not often a Professor, but it’s usually a student from the lab. And the one who is writing the businessplan and who is trying to find a funding is this young entrepreneur who is not much experienced. So that’s what I see most of the time. #00:15:33-2#

It’s not… So I’m not sure why you are asking me this but it’s not an external consultant who has some business experience and who is helping the entrepreneur to write his businessplan. There are many such people like the CTI coaches are providing guidance, but the one who is writing the businessplan, these are the people with the idea hereafter, because they are the only ones who understand in this state what they are doing. #00:16:05-2#

WM: OK, and now with regard to external entrepreneurs: Do you have frequent experiences with them? #00:16:18-2#

HLE: Yes we have. #00:16:19-1#

WM: And what are your experiences with external entrepreneurs – are they helpful or are…? #00:16:27-1#

HLE: So are you talking about entrepreneurs who would help these young people… #00:16:34-4#

WM: So a serial entrepreneur. #00:16:37-6#

HLE: Well two things: So it’s clear that if these young people, I am talking to you about, are going to investors it is more difficult for them to find funding. So if they can work with people with experience, like you are saying, it certainly increases the chance of rising money. We have an example, which is a company called “Aleva Neurotherapeutics” which is in the medical field and the technical founders tried for one or two years to raise money and he couldn’t. And today they found this serial entrepreneur and he managed to raise 10 million Swiss Francs. So it’s clear that Serial Entrepreneurs DO [!] bring some credibility. #00:17:20-9#

But I have also examples where these young entrepreneurs could raise the same amount of money with NO [!] Serial Entrepreneur (Examples such as Nexthink, Abionic, Distalmoition). So I am not not… it’s not clear to me that it’s statistically changing the situation. Now let me tell you something about Serial Entrepreneurs… – I am not sure but I think you couldn’t find it on SlideShare; I am also trying to do some research about entrepreneurs; I do not have time to publish serious papers but I go to conferences and I published some papers and I did one this is about Serial Entrepreneurs from Stanford University again, because I have access to a big data base of such people. And what I noticed is that Serial Entrepreneurs with time have a tendency to do worse than better. And I know that there is a paper from a Professor at Harvard (Josh Lerner) saying that Serial Entrepreneurs are important because they bring credibility to firms, and I agree. But they don’t increase… – according to me – they don’t increase the likeliness of success of companies. So I am not pushing for Serial Entrepreneurs, because Serial Entrepreneurs usually are too self-confident and don’t help young entrepreneurs to do their own homework about learning and doing. So gain it’s a debate, but I am not fully convinced that the young entrepreneur needs to be associated with a Serial Entrepreneur. Now a young entrepreneurs certainly needs to be helped by people who have expertise in start-ups and technology, for sure. But it’s a different story. They may not be entrepreneurs, they may be managers who have worked in other start-ups, they may be former employees. I don’t believe so much in Serial Entrepreneurs. #00:19:10-7#

I am happy to send you the link, I think I can find it on SlideShare… [see eMails] I am sending you now a 3rd eMail with a 3rd link and you can have a look at what I try to do, you will see. #00:19:49-9#

But clearly don’t misunderstand what I am saying: Experience of people in technology IS [!] helping entrepreneurs to build their company, but I am not sure it has to be systematic… – that’s all what I am saying. #00:20:09-0#

WM: I’m just sending you something [see sent eMails with the shortened/extended slides for the Foundation Process] In which cases could you imagine it is reasonable to include an external entrepreneur? #00:21:17-4# #00:21:27-0#

HLE: I think it’s reasonable to include an external entrepreneur when the young entrepreneur is very technically oriented but has no interested in business and is so shy that he does not know how to communicate his idea to the business world… – it can be investors, it can be partners, it can be customers. So if someone is only interested in the technical aspects of his idea, then he needs to be surrounded with the right expertise. But when an entrepreneur who has a great idea is also enthusiastic, knows how to explain simply what he does and he has the drive and energy to do it, I am not sure whether he needs so much people with experience versus just a co-founder who is as enthusiastic as him and can help him in solving the challenges that he will be faced with. So it’s mostly a question of energy versus experience. #00:22:25-5#

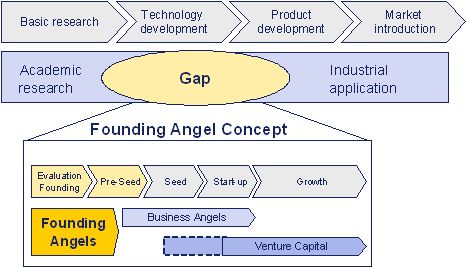

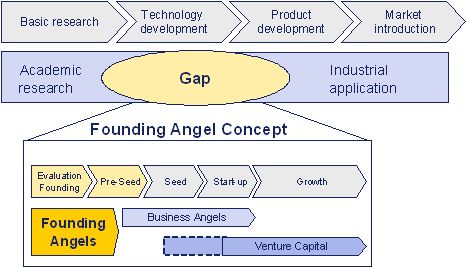

WM: For the next question please take a look at the first document that I have sent you [Slides]. So you see here the famous technology transfer gap and on the second slide you see the foundation process: On which step in the foundation process do you see the biggest problems of the young academics in creating their own company? #00:22:59-3#

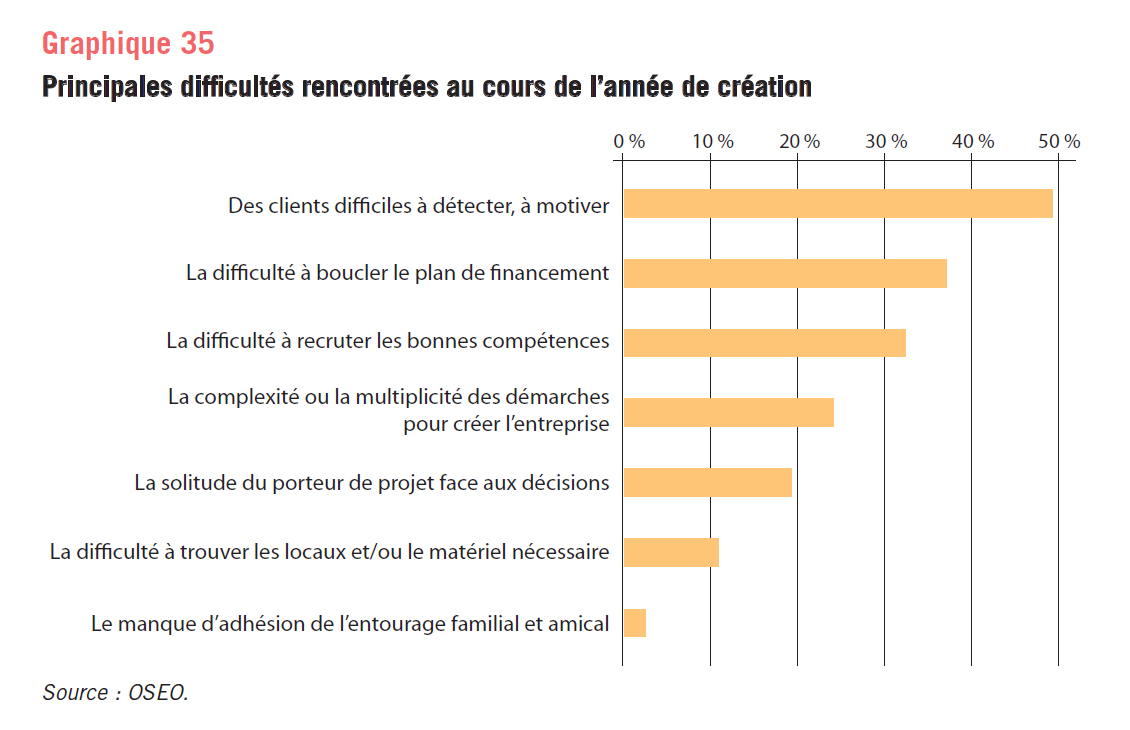

HLE: So the biggest challenge, and this is something I have heard so many times, is financing! Because, in fact, I am sure to can say it for ETH Zurich and EPFL, having ideas, helping them on the concept, writing businessplans… – you know, you all have these courses sponsored by VentureLab and CTI and even EPFL. Then create a company is not so difficult, you need a little money but it’s not so difficult, and once you have the money it’s easy to find… – even finding office labs is easy. But FINDING FUNDING [!] is a BIG [!] challenge [speaks very slowly and impressive]! It’s a BIG [!] challenge! Maybe because the idea are not good, it doesn’t mean that the money is difficult to find because these people have ideas which shouldn’t be founded. But for me this [rising funding] is for what I see the biggest challenge. #00:23:52-5#

WM: And for the other steps, you do not see any bigger problems? #00:24:03-5#

HLE: Well I am not saying it’s easy, it requires a lot of help, but so I am looking at your second document [extended slides]: Technology Transfer and the Foundation Process. Technology Transfer: some people complain that it’s a lengthy process and it’s difficult to negotiate with universities, but for me there is not much problem. Businessplan competition: There are so many, as you are writing, competitions on courses… – I think someone who is motivated can do it. Consultants: you have tons of consultants from the CTI start-up process, so you can find these people who are helping you. But THEN [!] finding… – I am not even talking about venture capital, because it nearly doesn’t exist in Switzerland, but if you are looking at Business Angels, it’s VERY [!] difficult to convince them and it’s very lengthy and it’s for very little amount of money. I don’t know if you noticed, there was in TechCrunch – this is this big website – the announcement of an EPFL start-up called BugBuster which raised one million Swiss Francs. And TechCrunch said: “Well the Swiss scene is such that a series A-Round is one million, whereas in the U.S. a 1-million-round is more an Angel round and a serious A-round would be 5 million. #00:25:21-5#

So there is such a lack of understanding about the funding needs, there is a difficulty. Furthermore there is no venture capital. And then technology centers… – you know, you have the Technopark in Zurich, we have our Innovationpark, there are so many office space for start-ups, so I don’t think that it’s an issue. I didn’t see as much difficulties there as in the funding. #00:25:45-3#

WM: OK, you now mean…?! What is not the difficulty? #00:25:52-3#

HLE: So the difficulty is ONLY [!] in funding and everything else is… – it’s a challenge, but it’s a small challenge compared to finding money. #00:26:00-7#

WM: But my question / research question now is on external entrepreneurs. If you go in the second document and there on the first slide you see that the BAs and VCs they enter in a later stage in the foundation process, but exactly in the very early stage there is a financial and operational gap. And here I am working on an idea that was developed by a colleague of mine called “Founding Angel”, those are people who do provide funding… – yes, but they are just co-founders, so it’s from the idea very close to Business Angels, but they start right from the beginning in the area of business idea and business concept development, and then they are co-founders. Typically they have a technical background as well but also experiences in start-up creation. And I am working on the evaluation of this concept whether this would make sense to have such a model besides BAs and VCs. Because as you already mentioned there are some severe difficulties with these two types [of actors] and those difficulties might be overcome by such a FA. #00:27:53-8#

HLE: You are absolutely right. In fact if you look at the best, the biggest success stories in the U.S. in technology, you would often find such cases, as early as in the 50s or the 60s with Fairchild and Intel and then with Apple Computers and then again even with Google and Facebook recently. You find such people, if you have seen the movie “The Social Network” on Facebook, you would see that you have Sean Parker and Peter Thiel, who were such people who helped Mark Zuckerberg and then they went to VCs. If you look at Apple Computers, Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak had no experience but there was a guy Mike Markkula who became a kind of manager and Business Angel. But what is interesting is that these people are OFTENTIMES introduced to the entrepreneurs by Venture Capitalists, saying: “Guys your idea is very good, but it’s still too early for us but maybe you should work with that guy, he might help us! And then depending on the development we WOULD fund you.” So and then in the case of Apple Computers, Mike Markkula was introduced to Steve Job and Steve Wozniak by Don Valentine, he was a famous Venture Capitalist, and then later he (Valentine) invested in the start-up. #00:29:22-8#

The difficulty in Europe is: Who knows these people? Do they even exist?! Because the big challenge is that a start-up has nothing to do with an established business. So if you go to Nestlé, if you go to a big SME, asking these people to help these entrepreneurs, they may provide traditional business advice, which has nothing to do with the advice we need for high-growth companies. A high-growth company is a very specific entity, so what you need are people who know exactly how start-ups need to grow and these people do not exist in Europe because they have never done start-ups themselves, they are more managers of established companies. So in the U.S. it works, but in Europe in many, many cases I have seen such people who have have given BAD [!] advice to entrepreneurs. #00:30:12-0#

But it’s still a good idea. #00:30:15-3#

WM: But isn’t it exaclty what I say: so these Founding Angels, they are typically experienced founders, so serial entrepreneurs with a technical background and they line up with researchers in a very early stage, so they go into a university to Professors and talk to them informally about new ideas and then they decide if the personal chemistry is right… #00:30:43-7#

HLE: Now let me ask you a question: In the Zurich area, there have been some similar examples but it’s not exaclty what you are telling me now, because what I see is such people are not going to the professors to evaluate ideas. They are going to young entrepreneurs who have already decided to do something and then they help them. If you look at the case of Sensirion which is a very good spin-off from ETH Zurich, right: Felix Mayer, for example the founder of Sensirion is now helping entrepreneurs like the founders of Optotune. So he is doing what you are mentioning, but now he is helping entrepreneurs, I am not sure whether he is helping Professors. The difficulty I see is that I have the feeling that Felix Mayer is very friendly with the concept of building a big SME, but I’m not sure he’s building start-ups the American way. But he is doing that, so it’s an example. #00:31:42-2#

But I am not sure Felix Meyer has the time to go in the labs and assess technologies, he has the time to be the board member for entrepreneurs who want to do things themselves. I don’t think Felix Meyer would leave Sensirion, but he has the time to be a board member. #00:32:01-4#

Well I have the feeling that you are talking to me about people who would become manager of the start-ups, maybe the CEO. Whereas I’m telling you, I see people becoming board members and giving very good advice. Do we agree on what I understand from what you are telling me? #00:32:13-4#

WM: Yes, I know what you want to say. But I have to say that I am personally a little bit involved in a small start-up company through a part-time job, which is in the biotech area. And there was a Professor from the University of Frankfurt in Germany in Biochemistry, he has developed some yeasts for producing 2nd generation biofuels and then he matched up with such a Founding Angel, who is by the way also my boss and they decided together: “Hey let’s found a company together!” The Professor is still at the university and they are developing their technologies further, but the other guy is managing the company, they have 50:50 shares, so it’s an equal participation. #00:33:19-5#

HLE: But if the company needs to grow, to go to the next step of going to funding: Who would manage the company? Would this Business Angel [means FA] be able to be the full-time CEO or is he just… #00:33:32-7#

WM: He is the CEO until financing is guaranteed and then there is a full-time CEO hired. #00:33:47-3#

HLE: Who is managing the technology? #00:33:47-3#

WM: The technology is developed by the academic scientists. #00:33:54-8#

HLE: But then you have to be careful, very careful about the way you manage all this, right. Because is the company just an extension of the lab or is it an independent entity which has it’s own employees? It’s always very difficult to manage such things right, because you still need someone who is technically oriented, but he is part of the company. Or maybe it’s still early, OK, I see your point. I understand what you are saying, it’s something which I have seen sometimes, not so often because there is always a difficulty of how do you manage the TIME [!] of the people involved and are you sure that you are not creating distortions because the business guy and the technical guy are not fully aligned in terms of strategy and on the things ongoing. So it MAY [!] work, but do you have examples of famous start-ups that have been built this way? That’s my question to you. #00:34:53-5#

WM: The problem is that this expression, this idea is quite new; there are maybe several examples, but they are not aware of this name [so “Founding Angel”] or that this is a distinct model with different characteristics compared to Business Angels or Venture Capitalists. As you saw in my last eMail, I have sent you a second eMail […] #00:35:35-7#

I just know one of my colleagues at ETH, Lesley Spiegel, she is very active with start-ups, and there are also some students coming to her asking for some advice for a start-up. I think at the beginning it was more planned as a coaching role, but now it has developed and now she is a co-founder. But she had never heard about this expression before. #00:36:19-7#

HLE: You know what is interesting Martin: If you look at the biotech industry, particularly in the Boston area around MIT and Harvard University, the Venture Capitalists themselves, the good ones, Versant and Polaris, are doing precisely what you are saying. They become the CEO, they put a little money, more than 10’000, usually up to half a million or a million, they do the job and when they have early validations, then they put a lot of money in it with other funds. So the Venture Capitalist are doing precisely that in the biotech industry. Why in the biotech??! Because in biotech, the business is quite simple, you have a molecule, if it works, it might be a blockbuster drug and if it does not work you stop early, but then you need to pull tons of money. And because these Venture Capitalists are usually medical doctors, they understand precisely how it is. But outside of biotech, it’s not so binary – does the molecule work or not?!? In all the other fields, medical devices or anything in information technology it’s about product development and it’s about understanding if the technology you provided is bringing something to the future product. And THEN [!] it’s much more difficult, because these Founding Angels, as you call them, need a VERY BIG EXPERTISE [!] in the field where they are. And then it’s difficult to have them to do it systematically for many ideas one after the other. In biotech a medical doctor can do molecules one after the other, so every three years you can change up to another one (A famous example is Christoph Westphal [2]. In that cases it’s very difficult to build an activity, an industry of these people who would create funds or their own money and they would do it systematically because the challenge for you or for an entrepreneur is: How do I find such people?!? How am I sure that for my specific project I find, in Switzerland, in Europe or in the U.S. someone who is eager to do that? So the concept is good but the matching is the challenge #00:38:33-8#

WM: But usually it should be… – maybe it’s actually not the case, but the perfect situation or how it should work is that they offer themselves to the technical scientists or at least to give the technical scientists… to be popular/known at the department if they [the technical scientists] have an invention… – this is the perfect situation. If they have a good invention and want to create a company but don’t know how, they would know who to call, that they always have the the tickmark next to the desk: “If I have something I would know who to call.” And such a person should only involve in such a project where is technically familiar with because it’s also his own risk, the risk of failure. If it turns out that he has not the glue e.g. about health sciences. #00:39:51-4#

HLE: So let me ask a 2nd question, which is the following: The idea is very early, as you are saying on your slide it’s the very early stage – how much money will you need to reach the state where you can go to the next, which may be Business Angels or Venture Capitalists? So how much time and funding do you need for the Founding Angel to validate the idea? #00:40:18-0#

WM: So I would say about two years. #00:40:18-9#

HLE: Two years; so how much money? #00:40:20-5#

WM: It depends… #00:40:24-5#

HLE: Let’s say half a million right, it’s half a million – two years, half a million. #00:40:27-1#

WM: Yes, typically this company is founded and the research is still done or further developed by the scientists employed by ETH. #00:40:47-1#

HLE: I am not saying the half million is provided by private money, it could be a CTI contract, but you need money. And of course this guy needs to feed himself, he needs at some point…. or he is rich enough, he does not need to work, or he still needs to have his own money. And if the research is done at the lab, I think you are right, it can be developed and it may work. But you have to think about: How does this guy fund himself? #00:41:17-0#

WM: This is his own problem, there is no salary, he is only shareholder. #00:41:23-2#

HLE: Because many times I have seen people coming to EPFL saying: “I want to help labs and entrepreneurs!” And I am almost asking them: “Do you need to be paid for that or you don’t need??” If you don’t need to be paid, then it’s great because you can do exactly what you are telling me. But if he needs to be paid, then we are in trouble because we don’t know how to pay these people. And most of the time, I tell you, they need to be paid. #00:41:44-2#

WM: No in this model, they are not paid, they feed themselves with former/previous exits, so they are financially independent. As long as… #00:42:03-4#

HLE: So Martin we have such people around EPFL, I can give you the name of people like… – maybe you have seen them also around Zurich. There is one guy called Colin Turner [3], there is another guy called David Brown [4]… (I give you more names in note [5] #00:42:15-9#

WM: Yes can you please send me the contacts – just afterwards. #00:42:21-5#

HLE: I will send you the name and then I can try to find the eMail and then I can even make introduction if you wish. #00:42:34-1#

WM: Yes, just send me the the name or the website. #00:42:34-5#

HLE: Well I’m just typing them in an eMail […] [see 3rd eMail] What is interesting is that these guys are precisely doing what you are saying, they are not asking to be paid, but they don’t become the entrepreneurs, they are board members. They are Business Angels and board members and they are most of the time founding Business Angels, but they don’t have a management position, they are on the board. #00:43:06-7#

WM: But this is also a characteristic: The Founding Angel, he is the manager as long as there is no other person. As soon as there is… afterwards when a BA or VC is involved and there is enough financing to hire a full-time CEO, then he goes to the board. #00:43:29-3#

HLE: You will have to check again, if these people who are founding Business Angels, can work with just the professor or if they really want to work with someone in the lab, who has the drive to become a technical founder, the CTO. Because a professor will become the CSO, the chief scientist, but someone who will become full-time… Do they need someone who will become full-time a technical guy in the company. That’s for me the key, one of the key elements… – another key element. OK I will send you the eMail about the 3 names. Anything else. #00:44:07-8#

WM: No that’s it, thank you. #00:44:14-1#

[…] #00:45:14-7#

HLE: But you have a good idea and it’s something many universities are trying to work on… – for sure. You can check what Alto is doing in Finland, the technical university in Finland, they have putted in place many things called Alto Ventures and they are all inviting formal entrepreneurs from the Finnish scene to help the people. So you could see there similar concepts. #00:45:44-6#

WM: OK I will take a look at it. Thank you very much for taking the time.

[0] Martin gave me more references on Founding Angels:

–Founding Angels as an Emerging Investment Model in High-Tech Areas by GUNTER FESTEL AND SVEN H. DE CLEYN,THE FALL 2013 JOURNAL OF PRIVATE EQUITY. (You may remember I had a post in teh past about De Cleyn’s PhD thesis…)

– Founding angels as early stage investment model to foster biotechnology start-upsGunter Pestel, 2011, Journal of Commercial Biotechnology Vol. 17, 2, 165–171.

[1] Philippe Renaud, the professor with 13 start-ups and http://people.epfl.ch/philippe.renaud?lang=en

[2] Christoph Westphal

[3] Colin Turner, http://www.linkedin.com/in/colinturnerswitzerland,

[4] David Brown http://www.venturekick.ch/index.cfm?page=129749&profil_id=2365&BackPage=129757,

[5] Francois Stieger, former Oracle executive, http://www.forbes.com/profile/francois-stieger/,. Another idea might be former CTI coach and executive, Jean Marc Wismer http://ch.linkedin.com/pub/jean-marc-wismer/0/a1/2a8 who is now CEO of Sensimed. Finally Jean-Pierre Rosat (http://startuptraining.ch/fr/portfolio-items/jean-pierre-rosat-2/ ) and Jacques Essinger (http://www.linkedin.com/in/jessinger) are quite famous here in the medtech field.

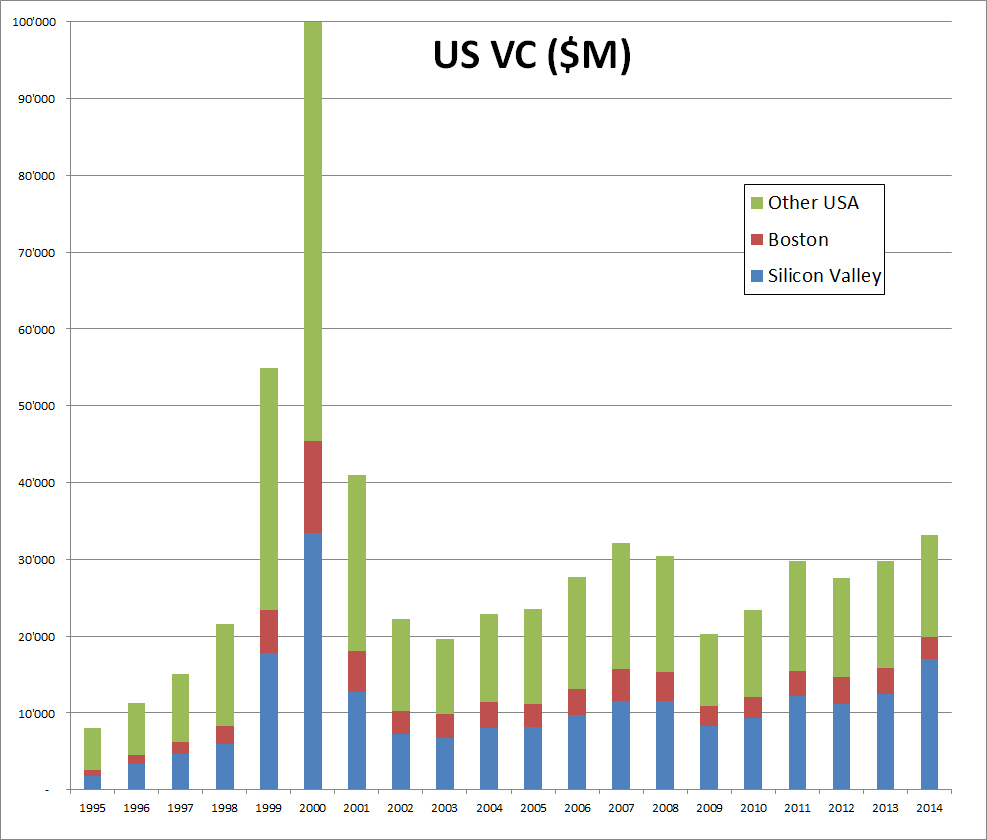

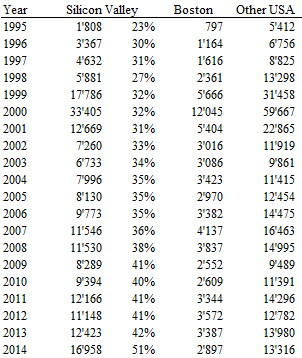

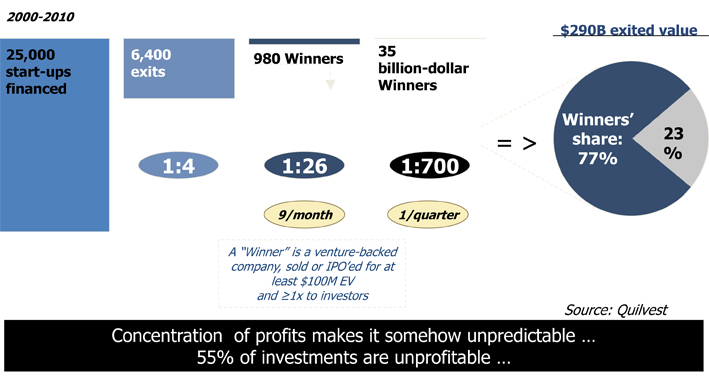

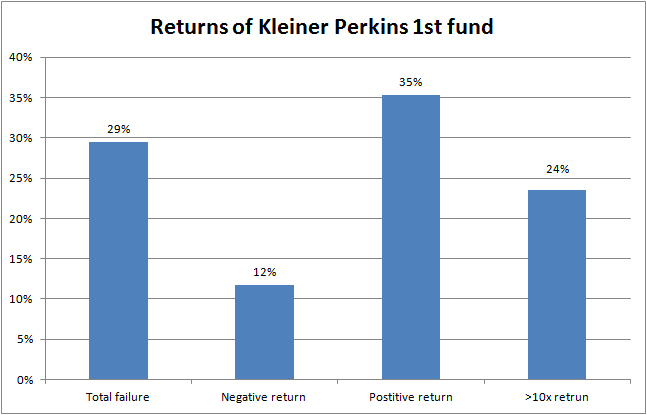

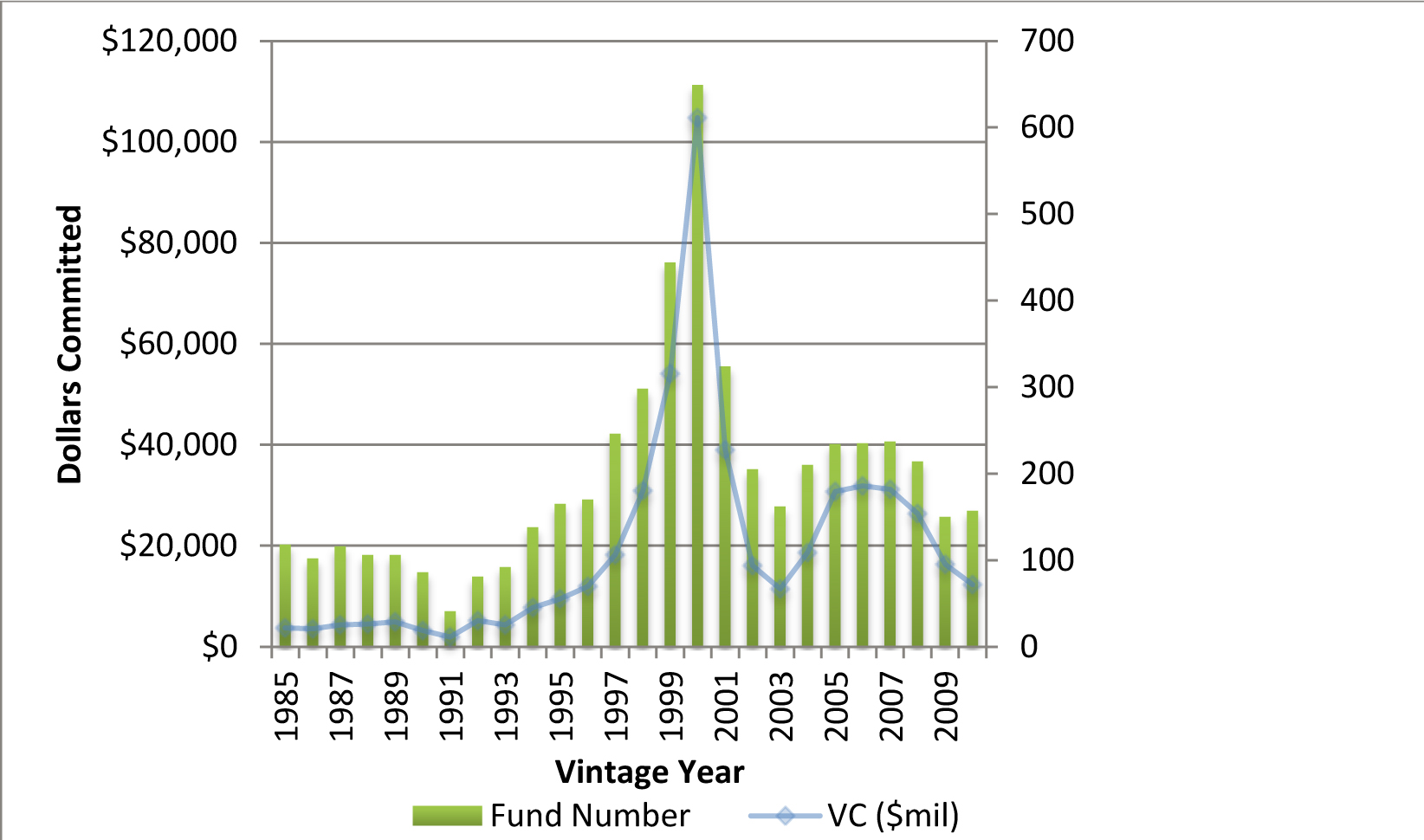

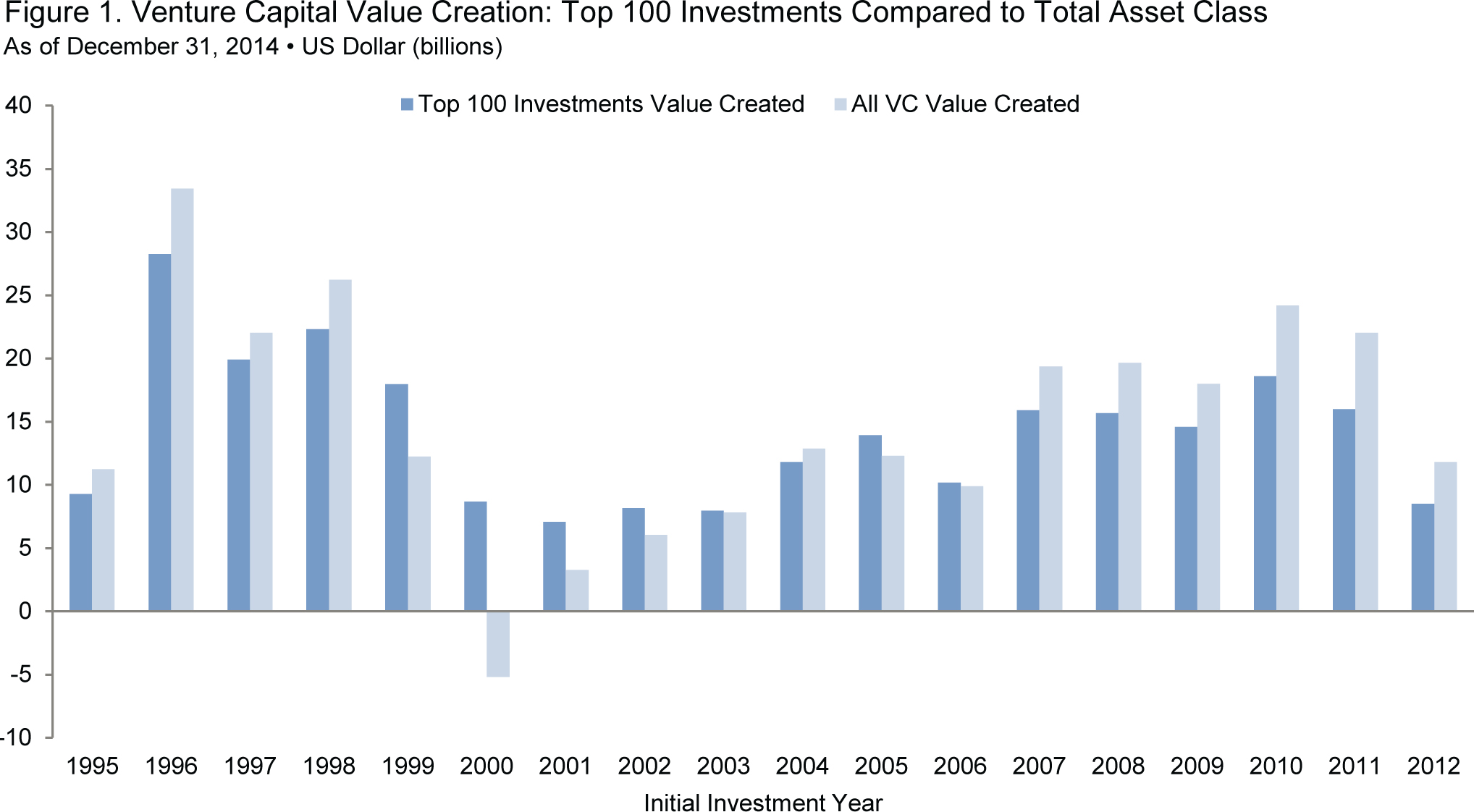

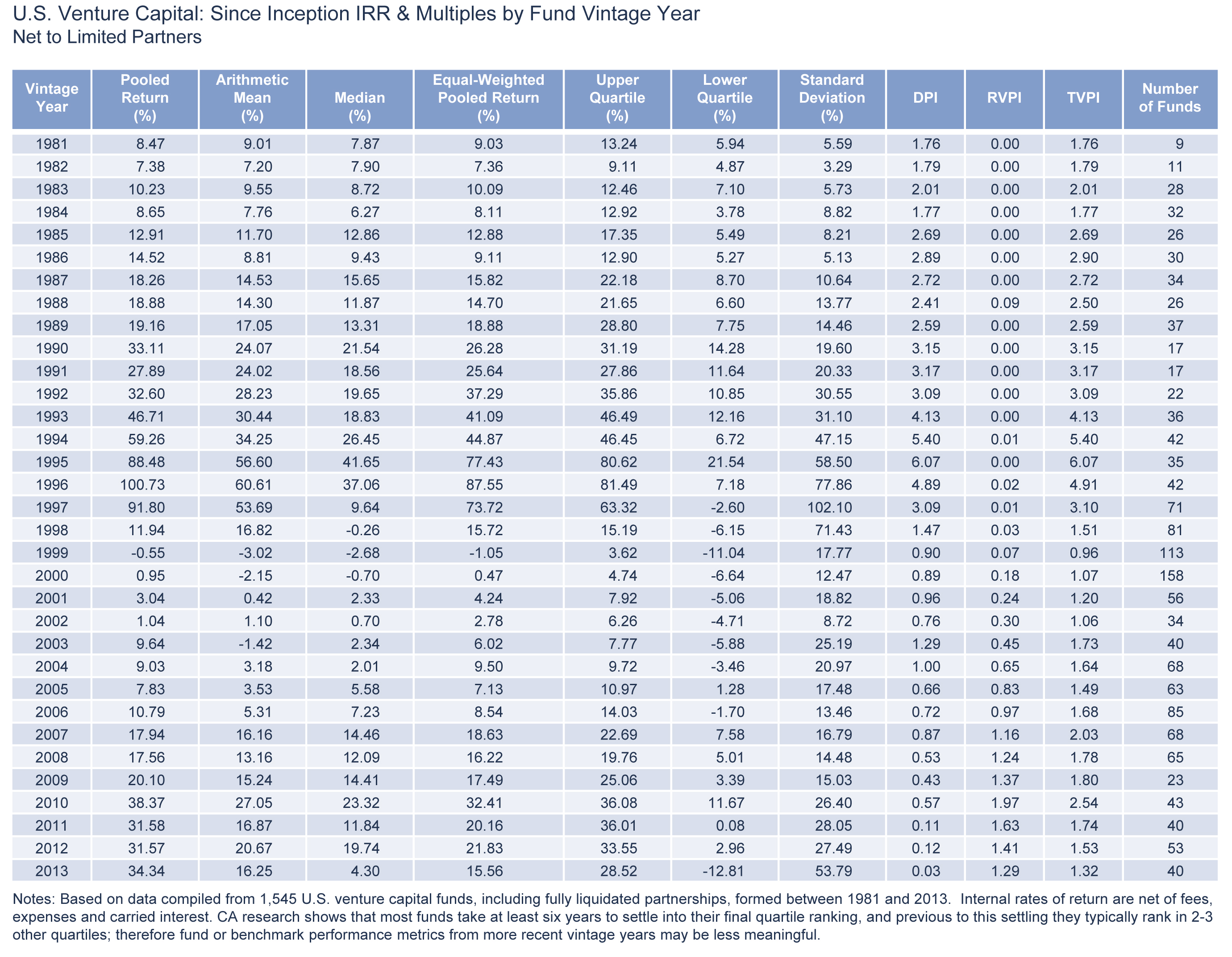

The VC gains according to Cambridge Associates

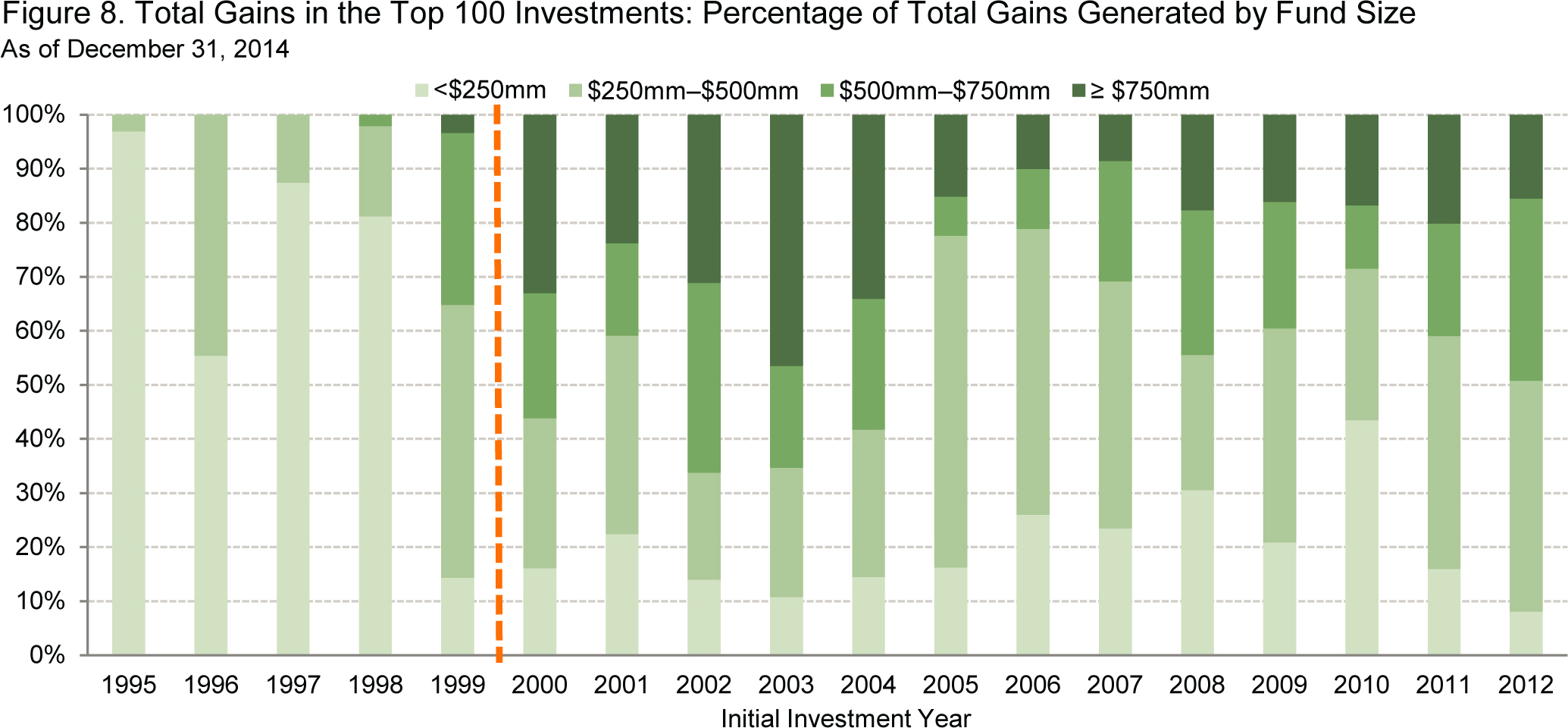

The VC gains according to Cambridge Associates The VC gains vs. fund size according to Cambridge Associates

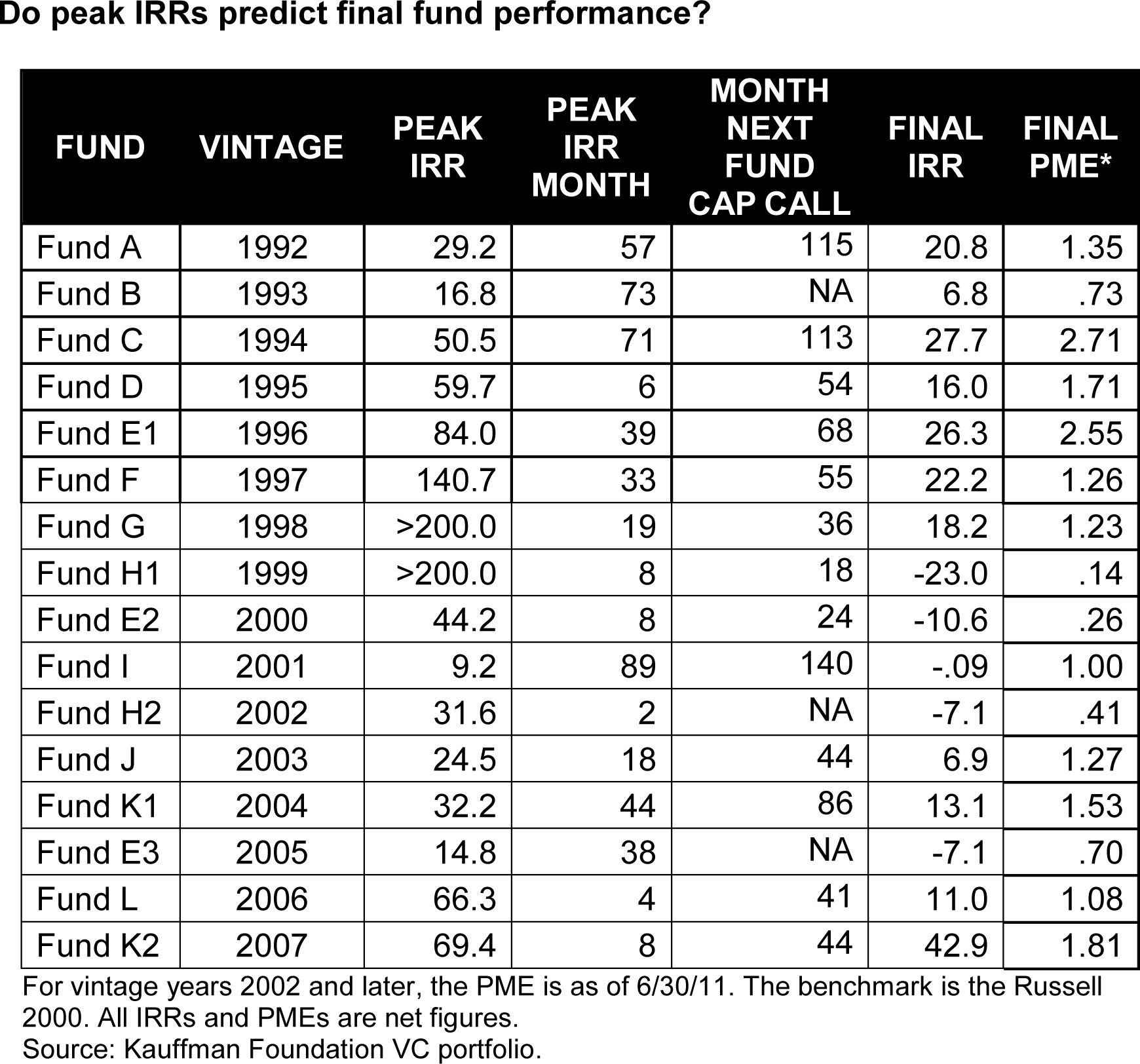

The VC gains vs. fund size according to Cambridge Associates The VC performance according to Cambridge Associates

The VC performance according to Cambridge Associates