This morning I was at a big meeting of the French innovation ecosystem and after a presentation about support to entrepreneurship, I took the liberty of asking a question about the importance given to entrepreneurs in residence, to serial entrepreneurs, but also to the idea of bringing together researchers and students in science and technology on the one hand and business school students on the other, the latter having a sensitivity to and perhaps more experience of business. I added that from my point of view, in entrepreneurship, at the international level, these concepts have had little or no impact on value creation…

I felt a lack of understanding about my question, which in itself is not surprising since these ideas have precisely been chosen to develop or encourage entrepreneurship. It wasn’t just a feeling as three people told me they didn’t really understand my question (although a few people in the audience seemed to nod and others came up to me later to thank me for asking the question).

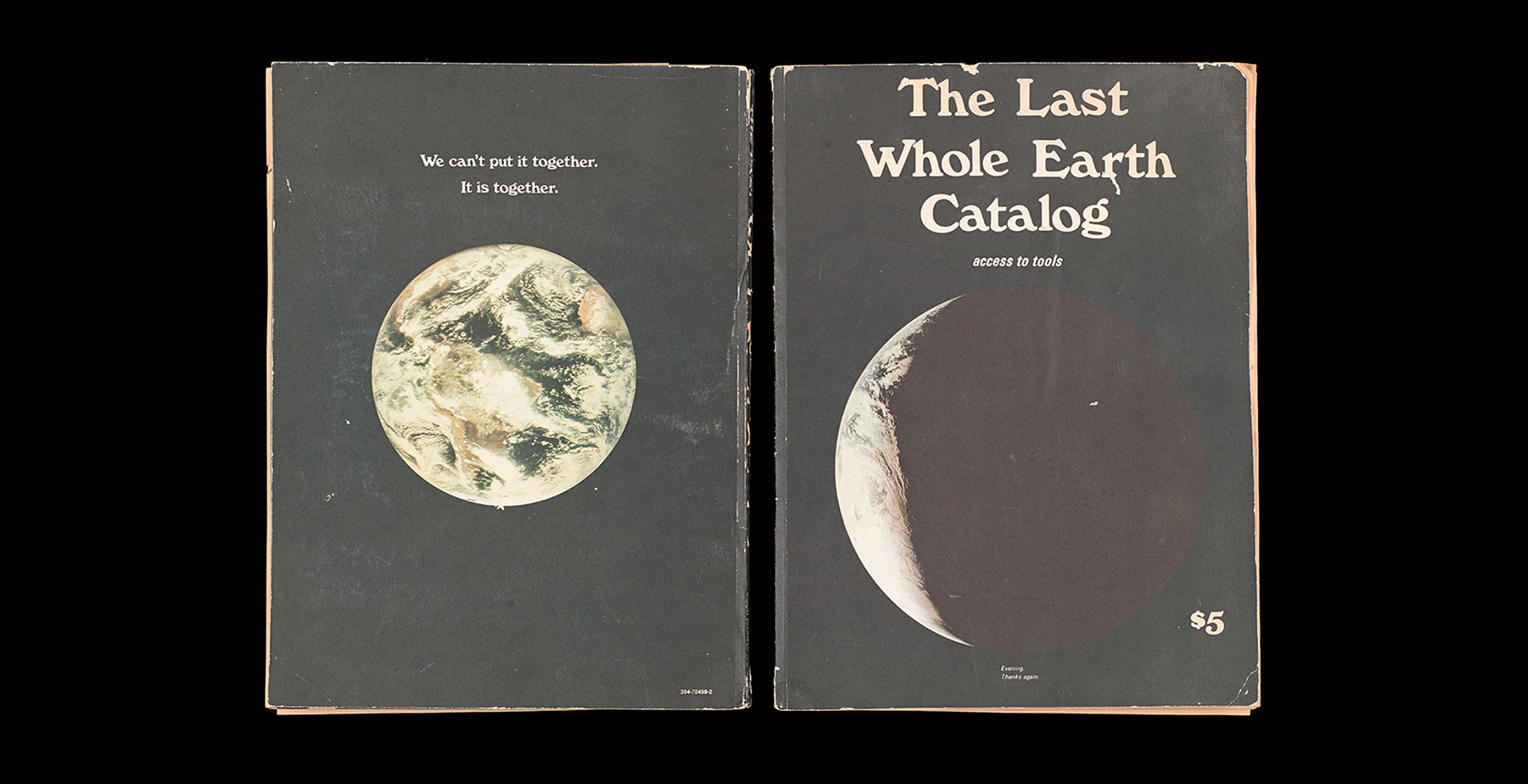

So let me try to develop my point of view and clarify the reason for the question. I have the strong belief, developed and confirmed year after year I think, that innovation is made by fairly raw talents. I’ll just recall one of my favorite quotes: “A few years ago, a major consulting firm published a report advising all companies to appoint a Chief Innovation Officer. Why? Allegedly to establish a “uniformity of command” over all the innovation programs. We’re not sure what that means, but we’re pretty sure that “uniformity of command“ and “innovation” don’t belong in the same sentence (unless it’s the one you’re reading now). […] Innovation stubbornly resists traditional, MBA-style management tactics. Unlike most other things in business, it cannot be owned, mandated, or scheduled. Innovative people do not need to be told to do it, they need to be allowed to do it”. If you are intrigued, you will find the context here.

The idea that people without experience need to be helped and supported (I’m not saying encouraged or stimulated) has puzzled me since I discovered the world of startups. Of course, it is difficult to enter a world that you do not know. You have to learn about it, to even confront it. But why a need to “manage” these (future) raw talents by offering them entrepreneurs in residence, serial entrepreneurs or even business school students?

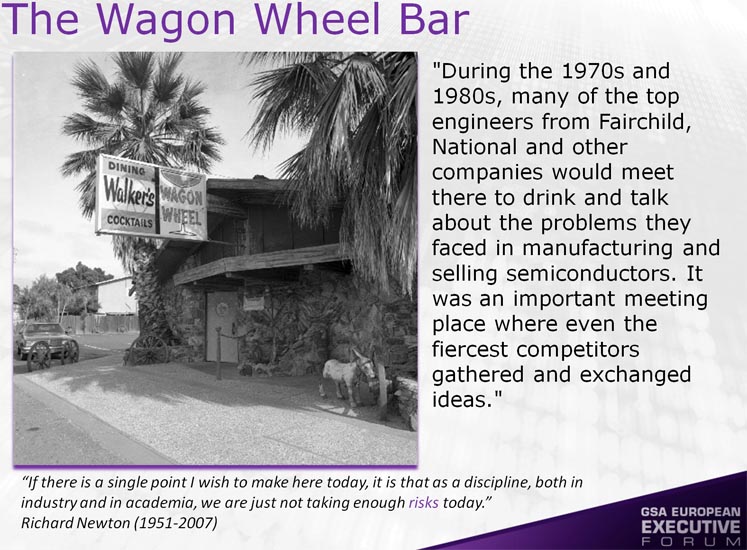

The truth is that we just need role models for these raw talents. Tom Perkins put it this way: The difference is in psychology: everybody in Silicon Valley knows somebody that is doing very well in high-tech small companies, start-ups; so they say to themselves “I am smarter than Joe. If he could make millions, I can make a billion”. So they do and they think they will succeed and by thinking they can succeed, they have a good shot at succeeding. That psychology does not exist so much elsewhere.

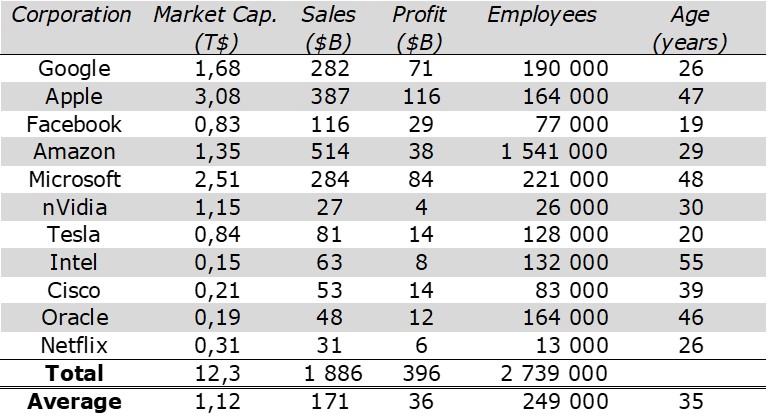

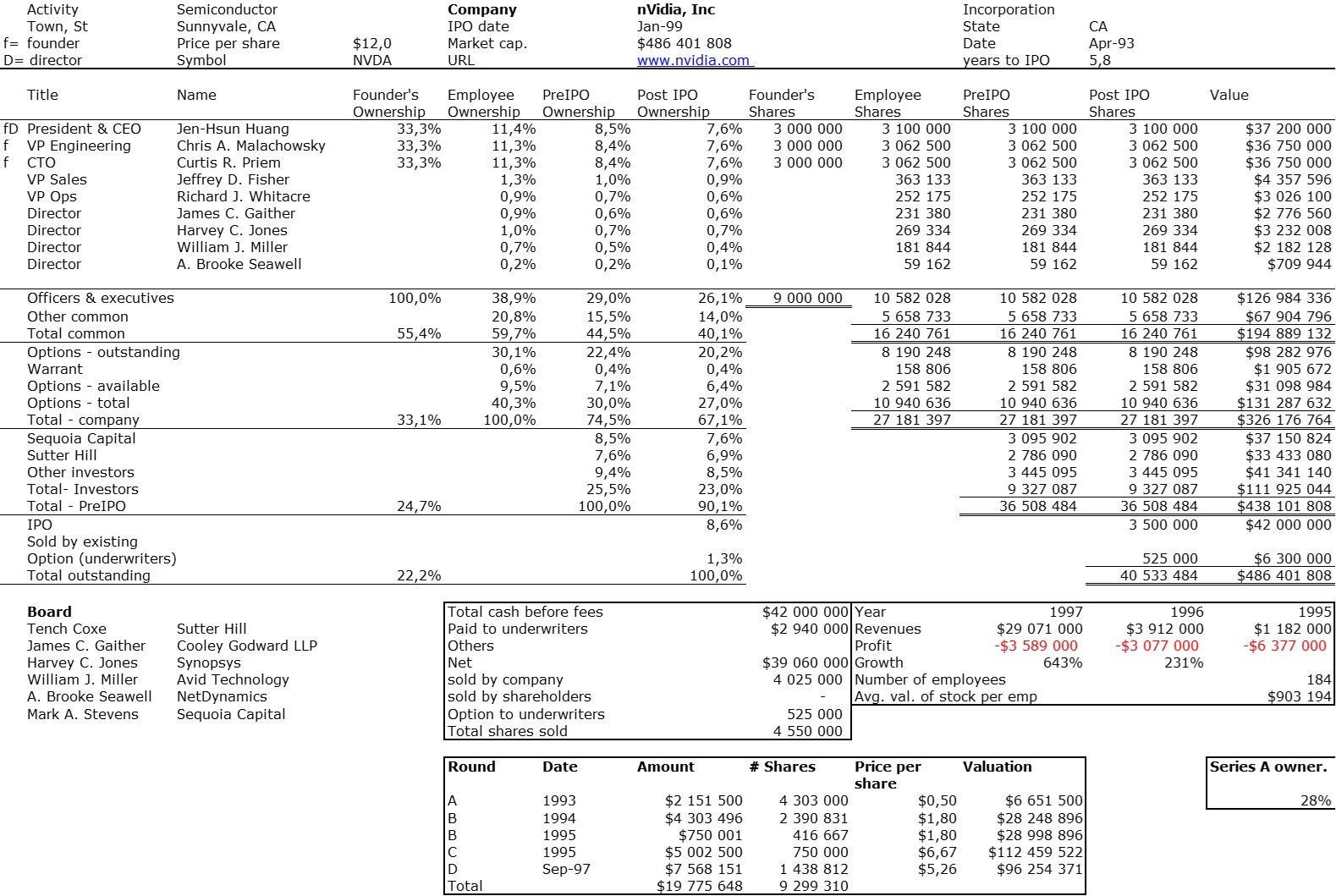

The Serial entrepreneurs, I have already analyzed their performance in posts that the interested reader can find here or there. As a short summary, their performance statistically deteriorates over time! I mention entrepreneurs in residence in an article that I translated here. Finally, the myth of the association between technical and commercial students is just as tough as the idea that we must combine technical and business profiles among startup founders. I remember anecdotally a seminar at MIT in 2004 where the same idea, then quite widespread in the Boston region of combining an MBA from Harvard and a PhD from MIT was dispelled as illusory. Which large startups bring together such profiles? I’ll let you think about it. Founders are above all people who understand each other and can work together. Later, they will look for the skills they lack.

Here is a very nice quote to drive the point home: Performance tools are great for augmenting operational performance. There is nothing wrong with that aspiration or the tools themselves; all companies can perpetually need to improve, and using best practice is indisputably efficient. But apart from connecting measurements with actual improvements, the platoon of executives graduating from business schools came to believe that the tools were the answer to everything, including how a company should strategize for something new to make money in the future. While the recipe for corporate success cannot be found in a text-book, and not everyone is an entrepreneur just because they have read a book on entrepreneurship, the dominating notion was that strategizing for something new was almost equal to finessing costs by a few percent every year, gradually improving sales tactics, analyzing a key performance ratio here and adding another staffer there, and generally being opportunistic. This comes from the very good The Innovation Illusion. Even more funny : Executive recruiters have not been scouting for entrepreneurial people like Elon Musk or Mark Zuckerberg to take up key positions in multinationals. They wanted executives with specialisms in optimization, management, logistics, capital markets, and other key operative functions of a firm. […] And these partners were planners, not entrepreneurs. And what about this: Can Business Schools Teach Entrepreneurship?

I will stop for now with my worriness about all this but quote with my recent favorite writer (without forgetting either the beautiful quote from Churchill, success is going from failure to failure without losing your enthusiasm). I am not talking about Churchill here but about Stefansson. He suddenly understands something, as if someone had suddenly lifted the veil of illusions that covers the world – which now appears to him as it really is. He understands that his conception of reality is there, before his eyes, printed in the words and images of this daily life that he has flown over every morning for years, unknowingly ingesting the vision developed in these pages. A conception of the world which is an assembly of stale opinions, stale ideas, all these things which have taken over and which we call dominant thought, what we call tangible realities. […] Besides, what is our deep nature, what is the adequate point of view, is this deep nature an illusion, perhaps we are nothing more than a container filled to the brim with dominant thoughts, consensual points of view, perhaps we almost never glimpse what free, independant thought is throughout our lives, except through a few flashes that are quickly snufled out, immediately extinguished by the standardized, stale and rancid ideas that distils the news, advertising, films, popular songs; songs of variety and truth? [Translated from the French version of Fish have no feet, p.274-76]