There is (sometimes) a love-hate relationship between entrepreneurs and investors. In fact there is a recurring message that Venture Capital (VC) does not provide an answer to the needs of many young start-ups. I will not enter that debate here as I do not have the answer. But as I recently read four different articles / reports where the current situation of venture capital is analyzed, I hope this post will be helpful to understand why VC is debated so much. These reports are:

– Lessons from Twenty Years of the Kauffman Foundation’s Investments in Venture Capital Funds (published in May 2012)

– Emergent models of financial intermediation for innovative companies : from venture capital to crowdinvesting platforms (publised in 2014)

– Venture Capital Disrupts Itself: Breaking the Concentration Curse (published in November 2015)

– Why the Unicorn Financing Market Just Became Dangerous…For All Involved, published in April 2016.

The Kauffman report

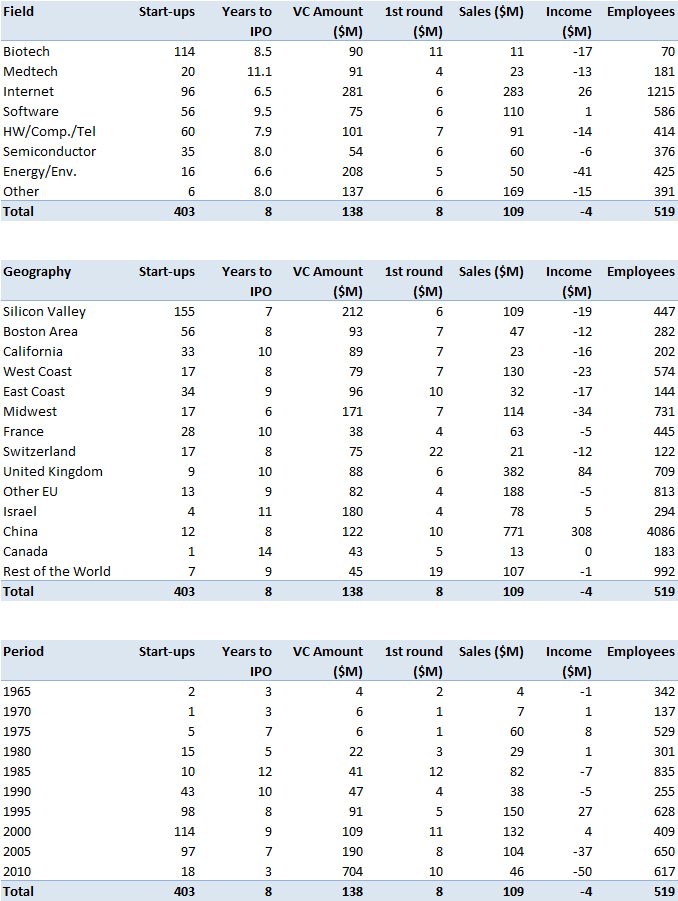

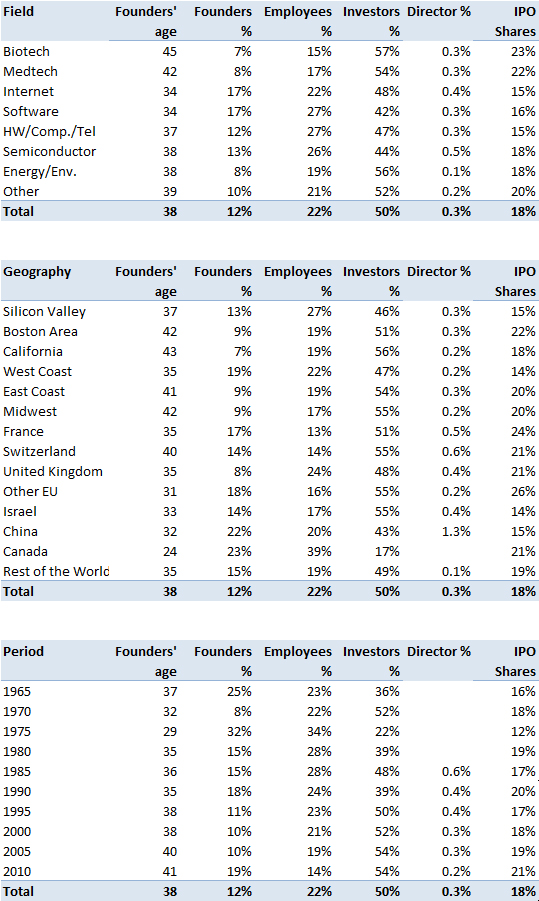

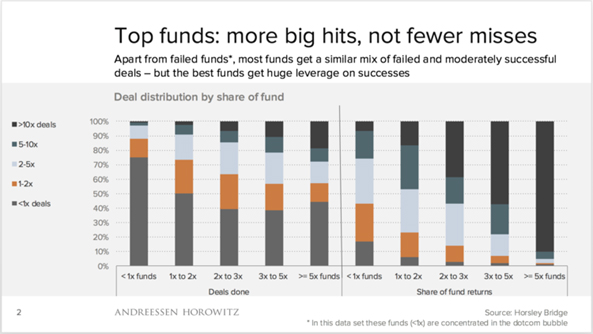

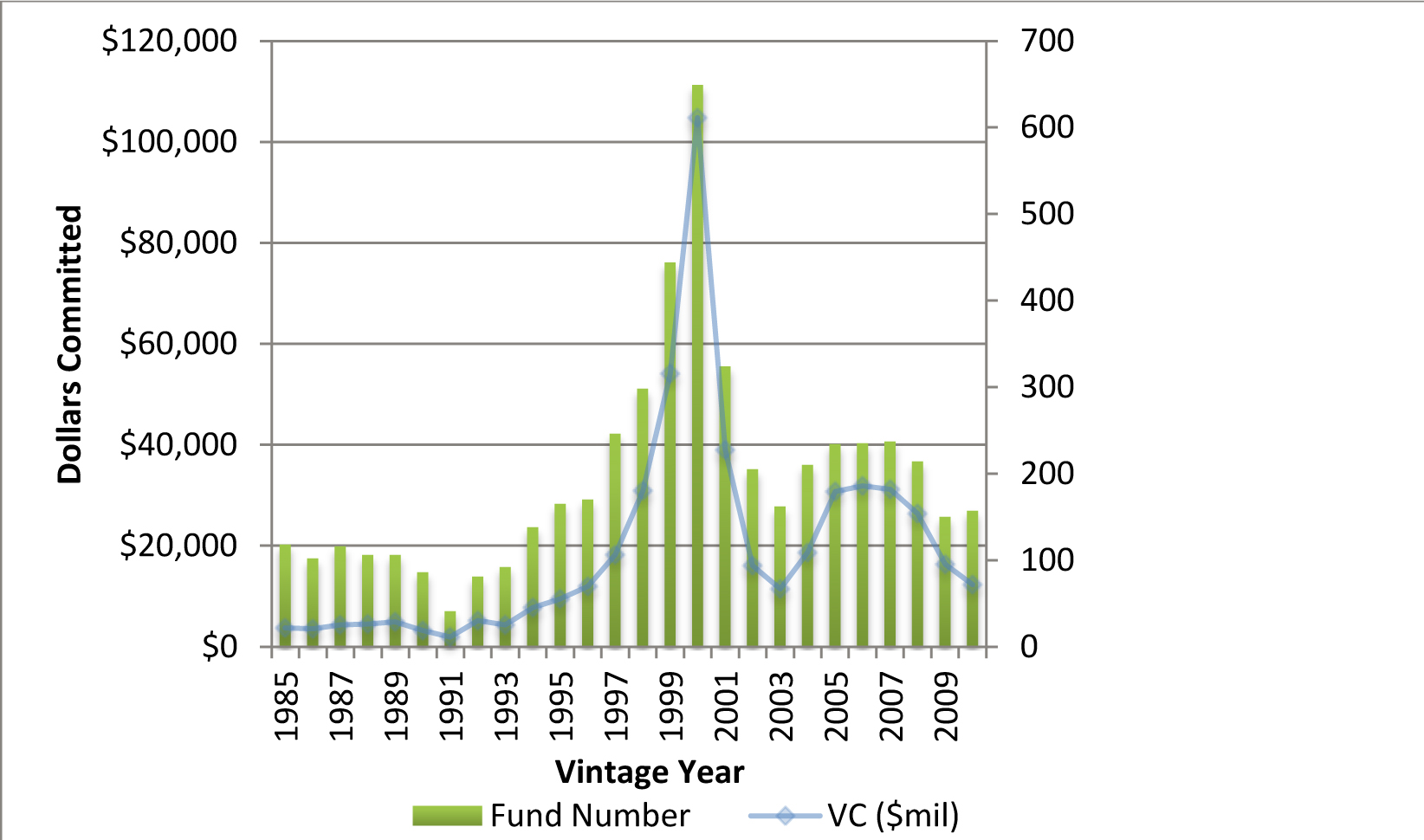

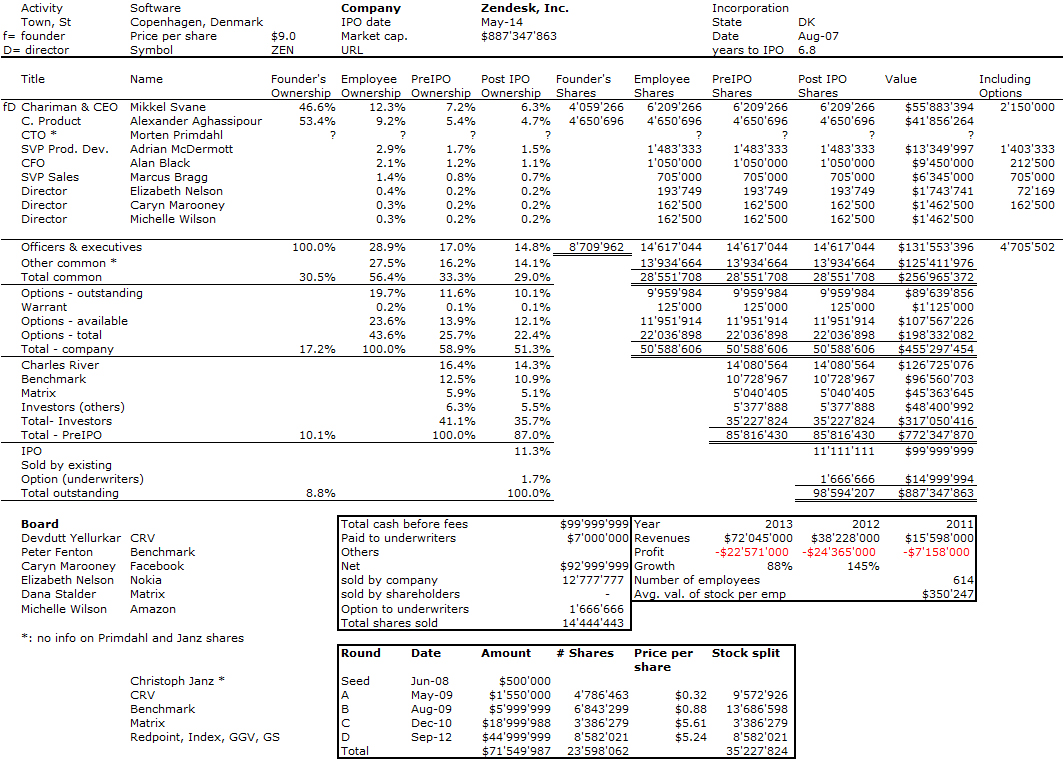

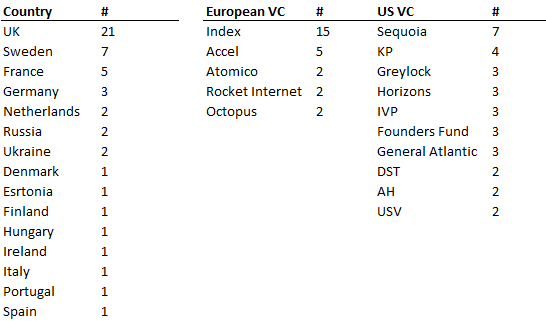

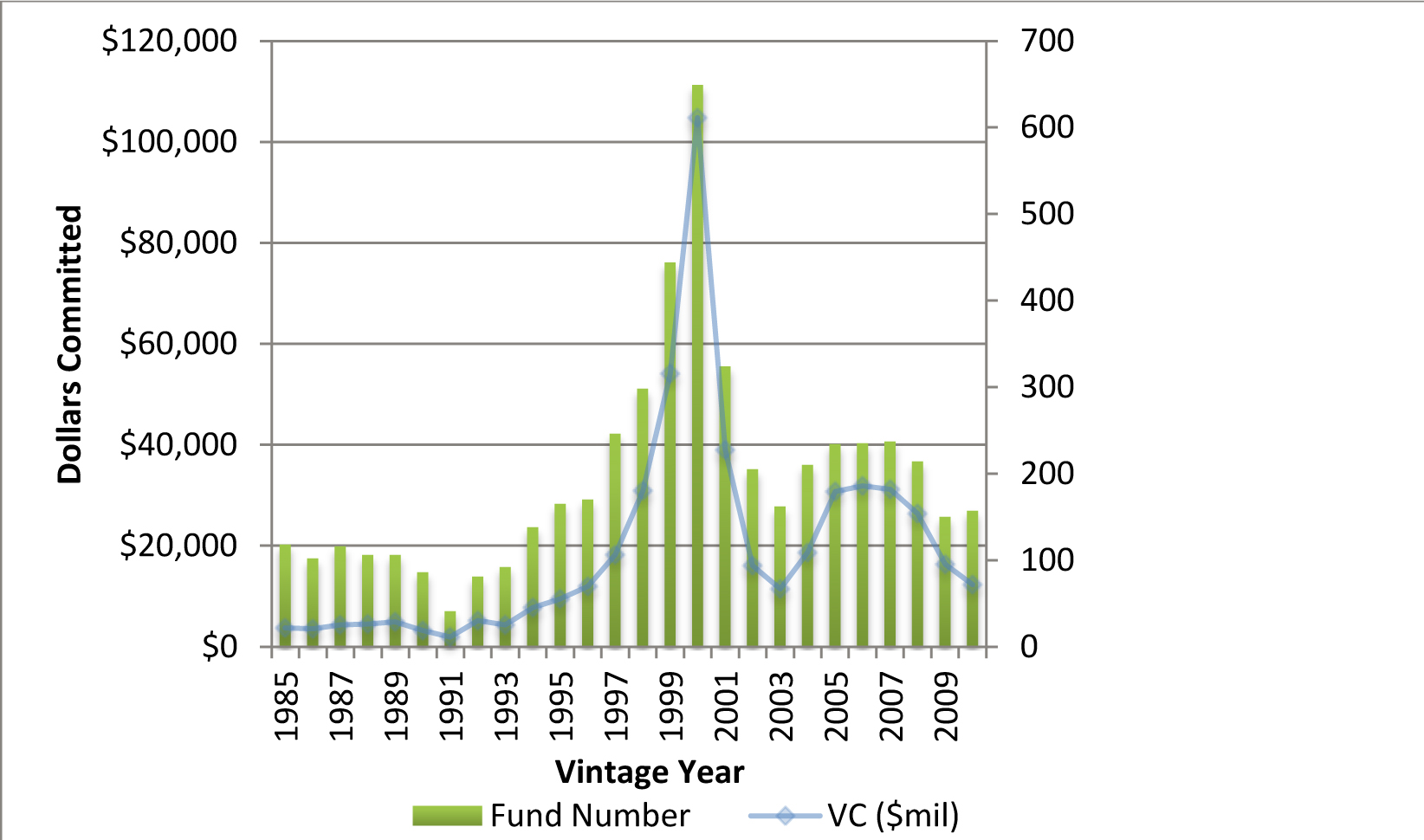

The Kauffman foundation explained in 2012 that the returns of venture capital have not been as good in the last 10 years as they were in the 80s and 90s. The reports also shows something which is quite well-known I think: the VC “industry” is much bigger than in the 90s, but with fewer funds. The explanation is simple: individual funds have grown from $100M to $1B+… The conclusion of the Kauffman foundation is that funds of funds, pension funds, limited partners (LPs) should be careful about where and how they invest in venture capital. Here are some graphs provided in the study.

The VC industry according to the Kauffman foundation

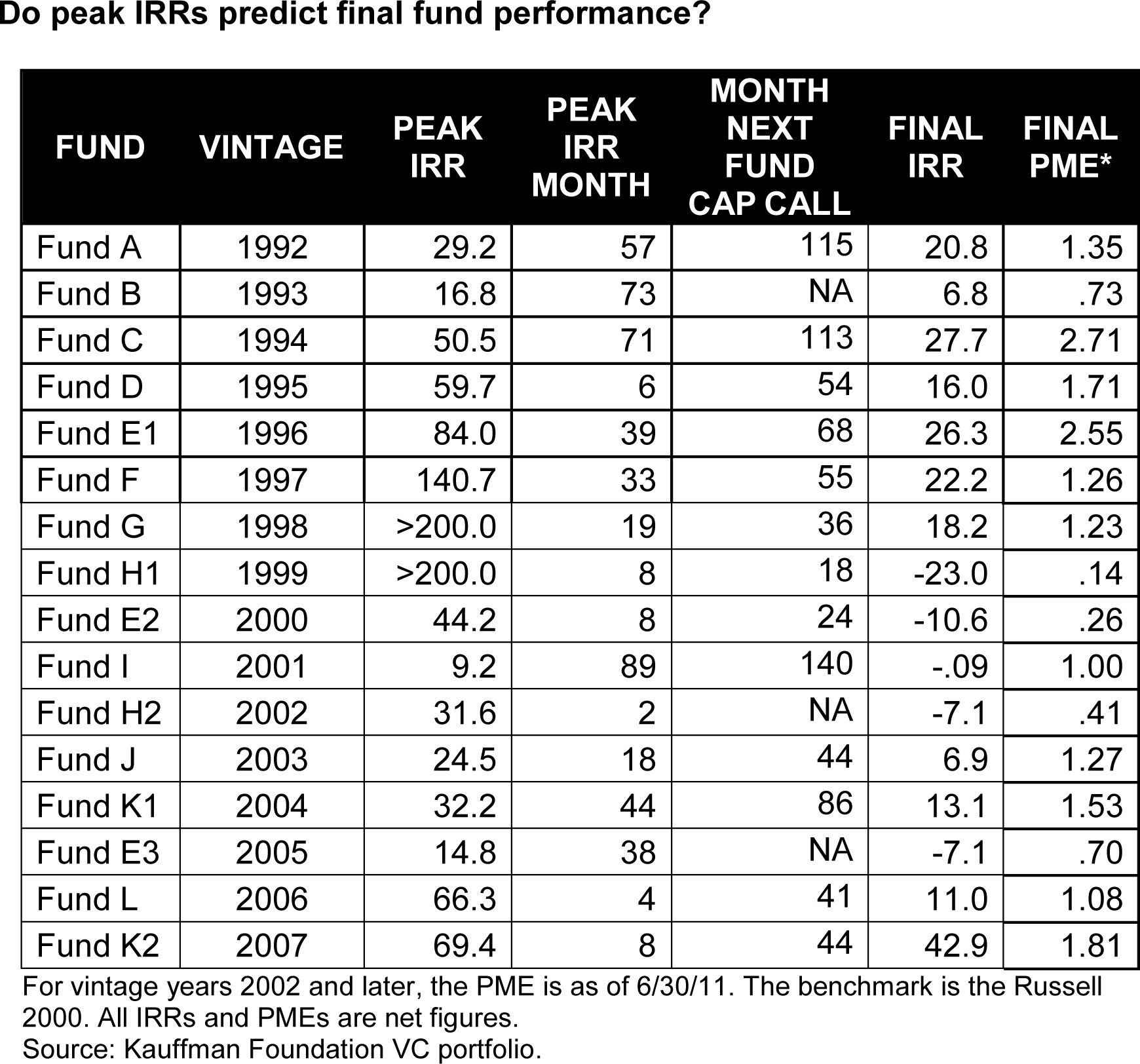

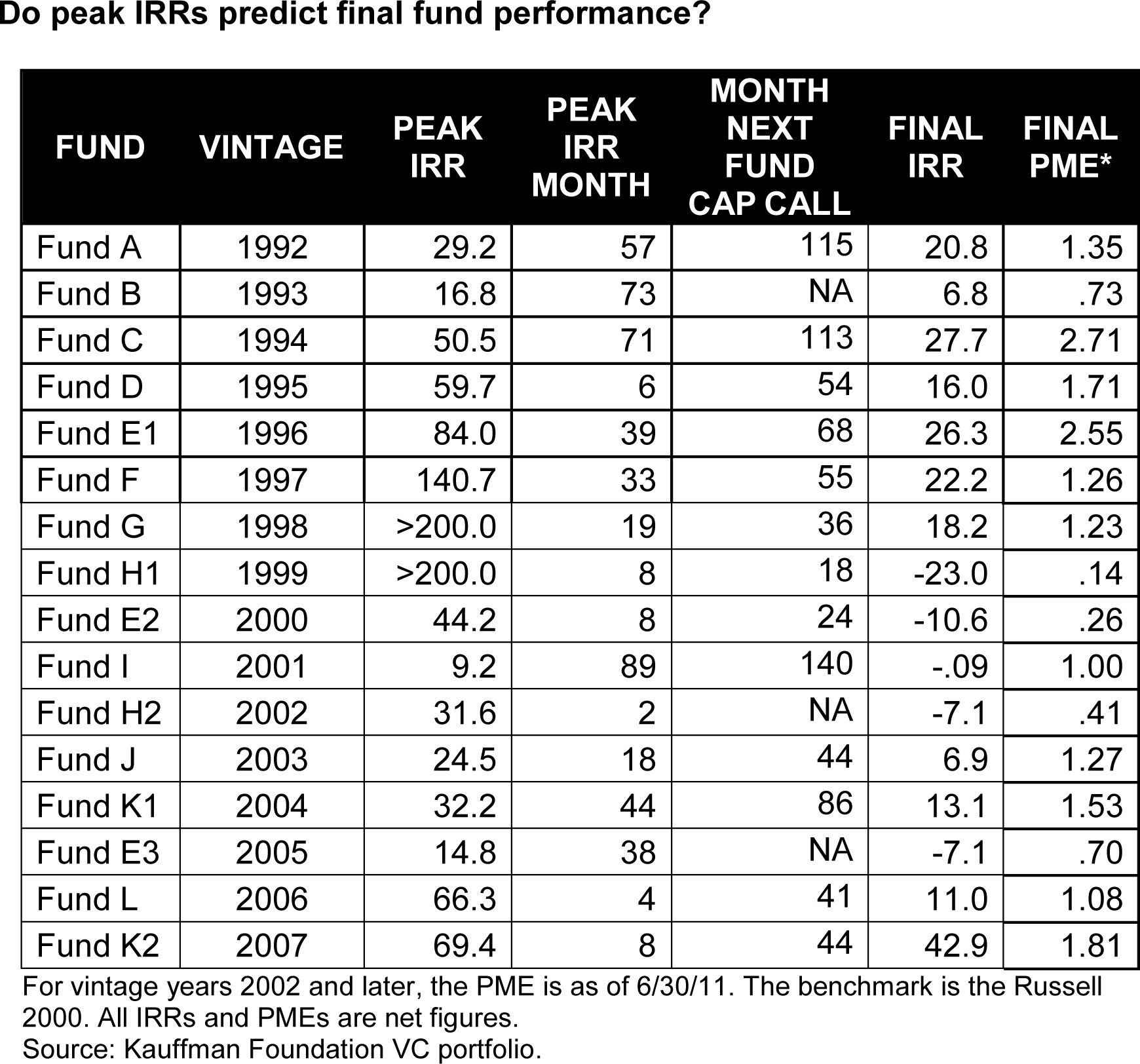

The VC performance according to the Kauffman foundation

In particular, you may see that IRR is a tricky measure as it changes over time (from peak value to final value) during the fund life. The Kauffamn suggests the following:

– Invest in VC funds of less than $400 million with a history of consistently high public market equivalent (PME) performance, and in which GPs commit at least 5 percent of capital;

– Invest directly in a small portfolio of new companies, without being saddled by high fees and carry;

– Co-invest in later-round deals side-by-side with seasoned investors;

– Move a portion of capital invested in VC into the public markets. There are not enough strong VC investors with above-market returns to absorb even our limited investment capital.

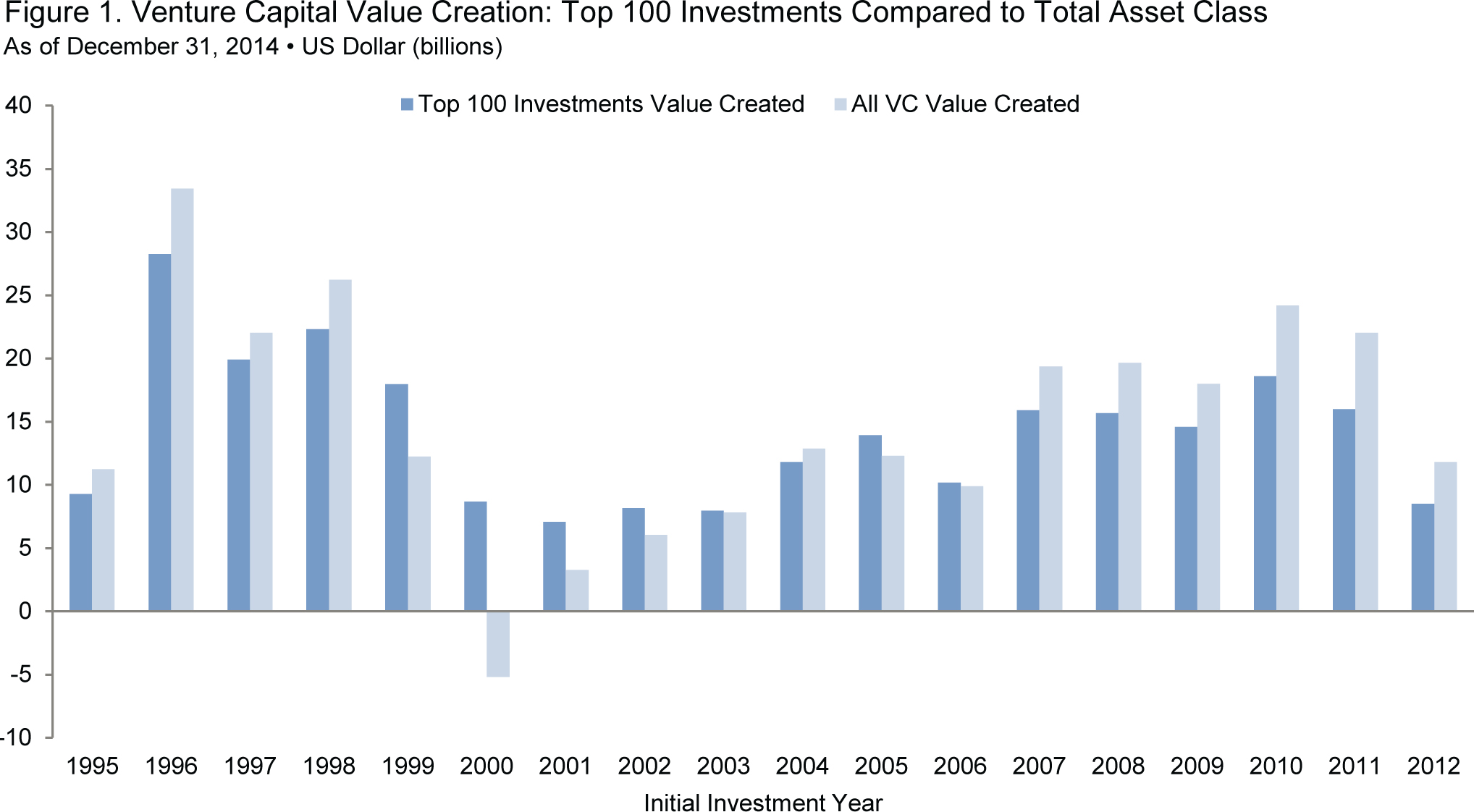

The Cambridge Associates report

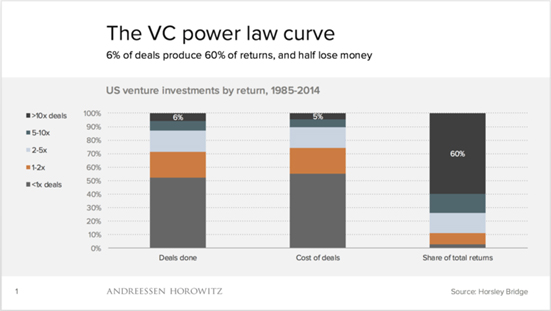

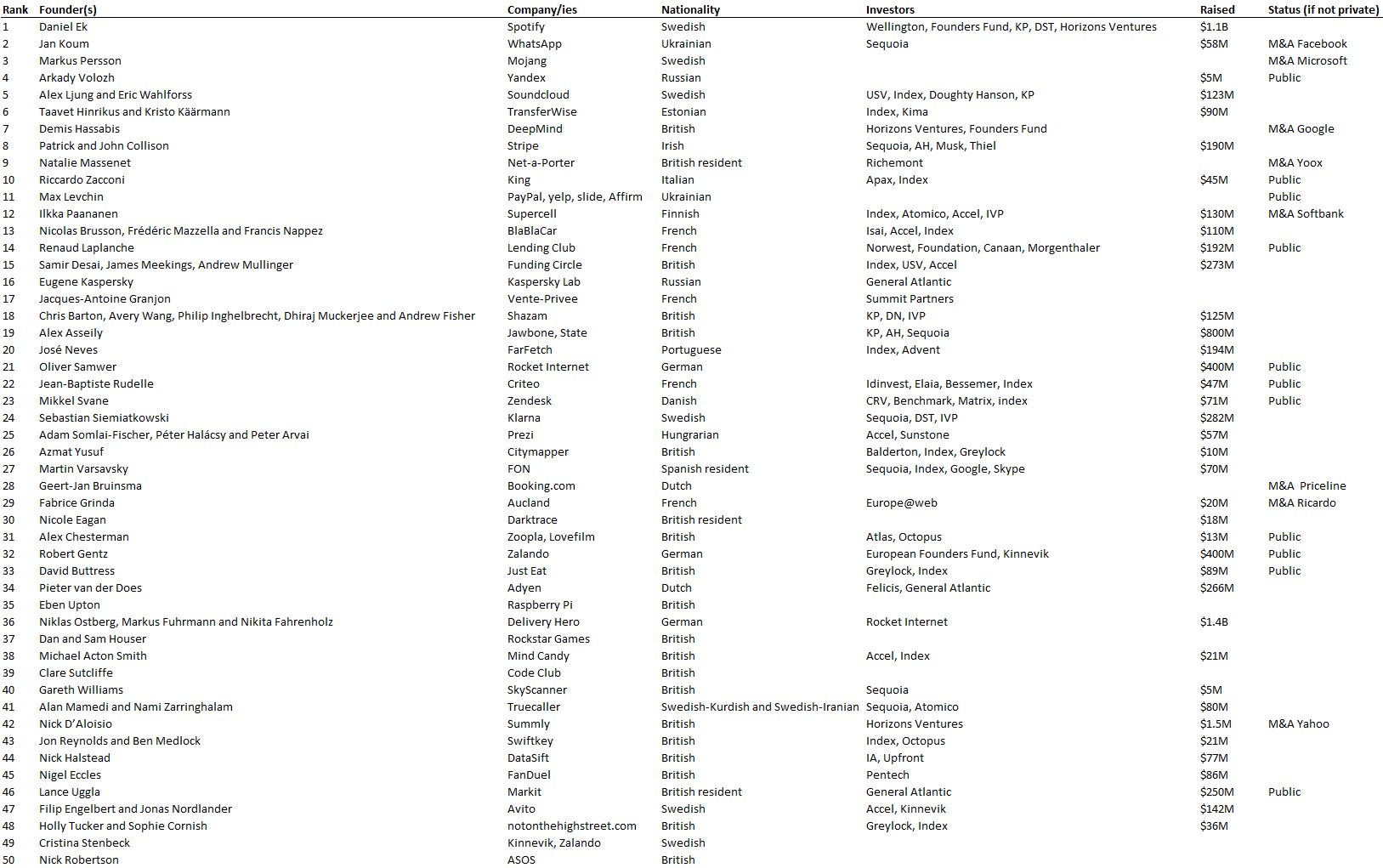

Cambridge Associates (CA) does not show a very different situation, i.e. there are indeed more bigger funds and a slightly global degraded performance. But CA also claims that the VC performance is not concentrated in a small number of high profile winners. Some elements of information first:

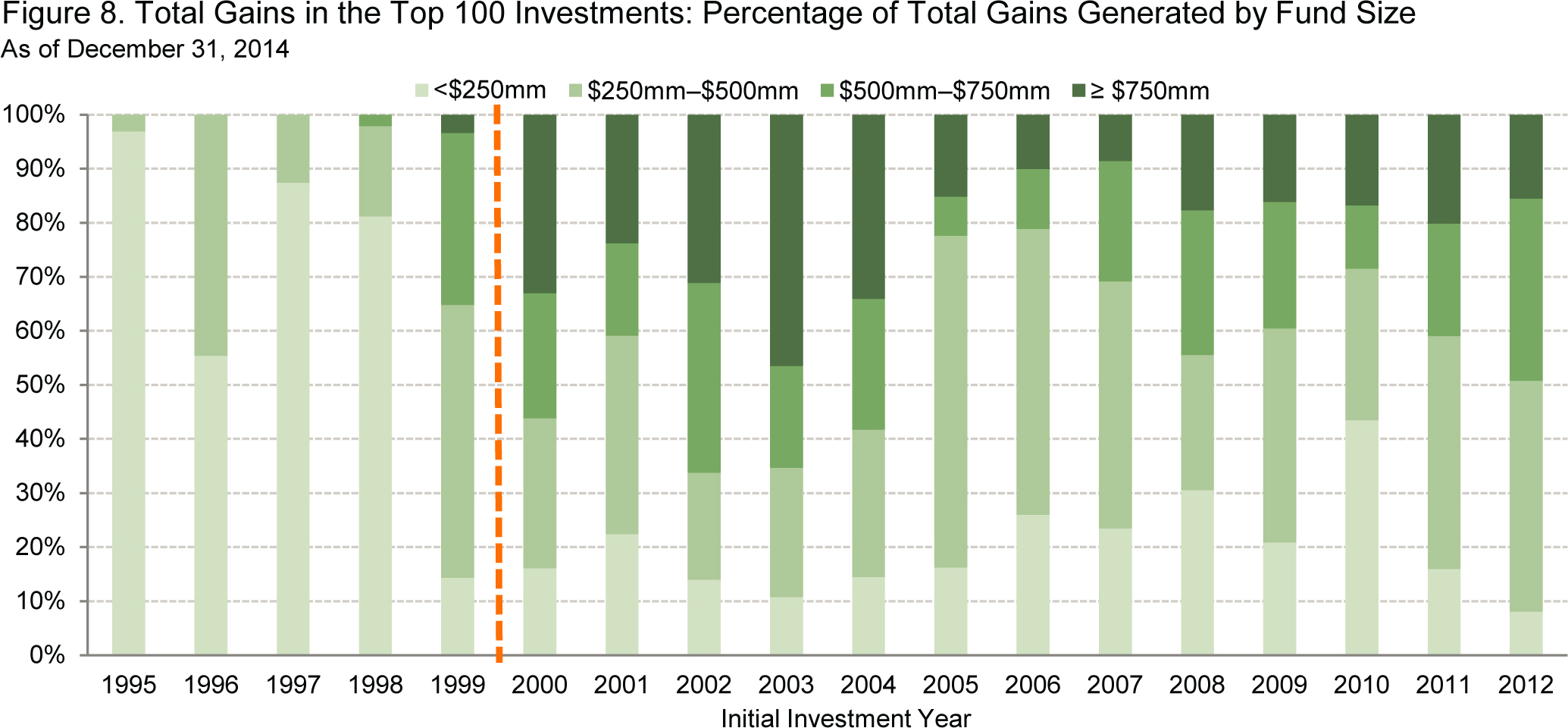

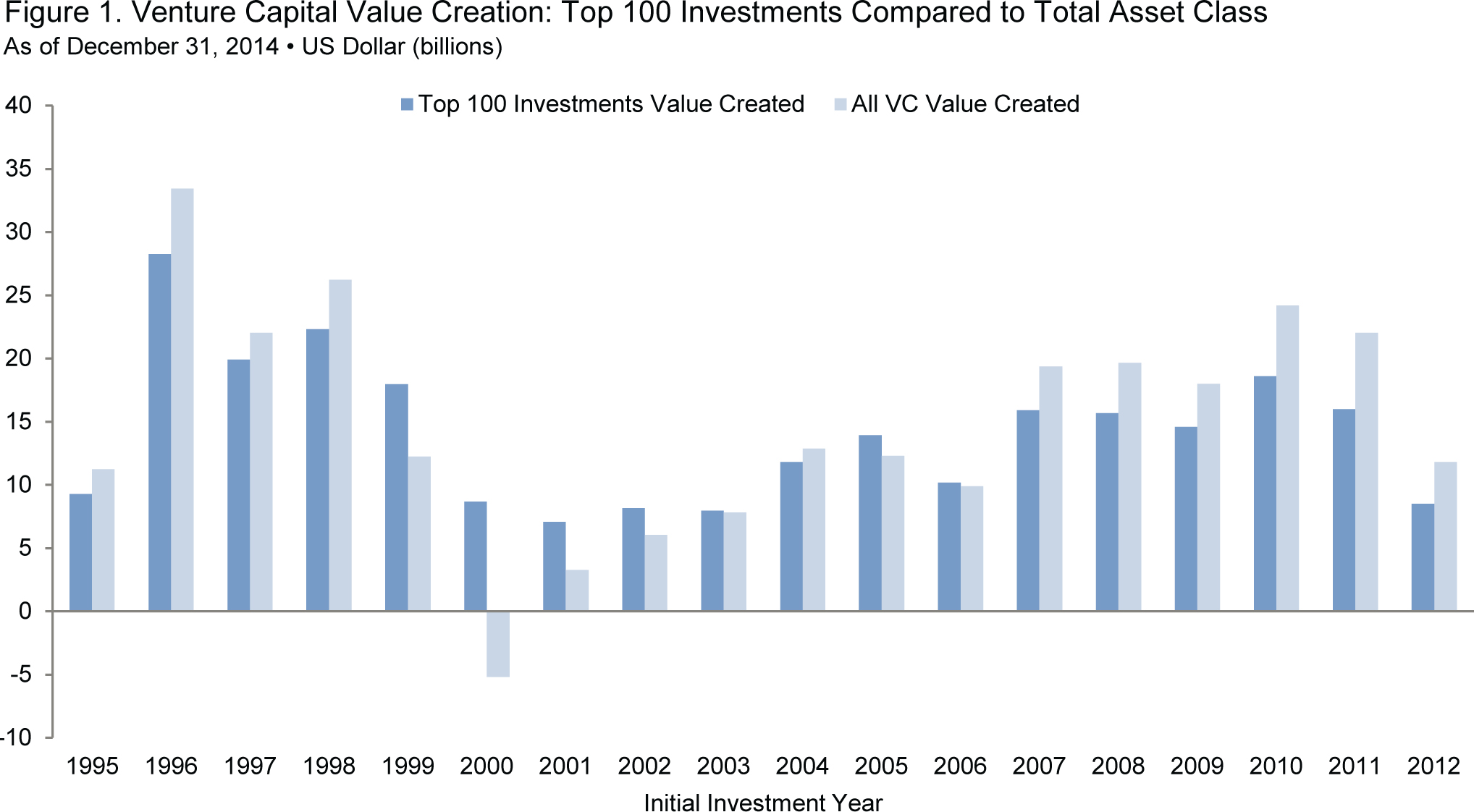

The VC gains according to Cambridge Associates

The VC gains according to Cambridge Associates

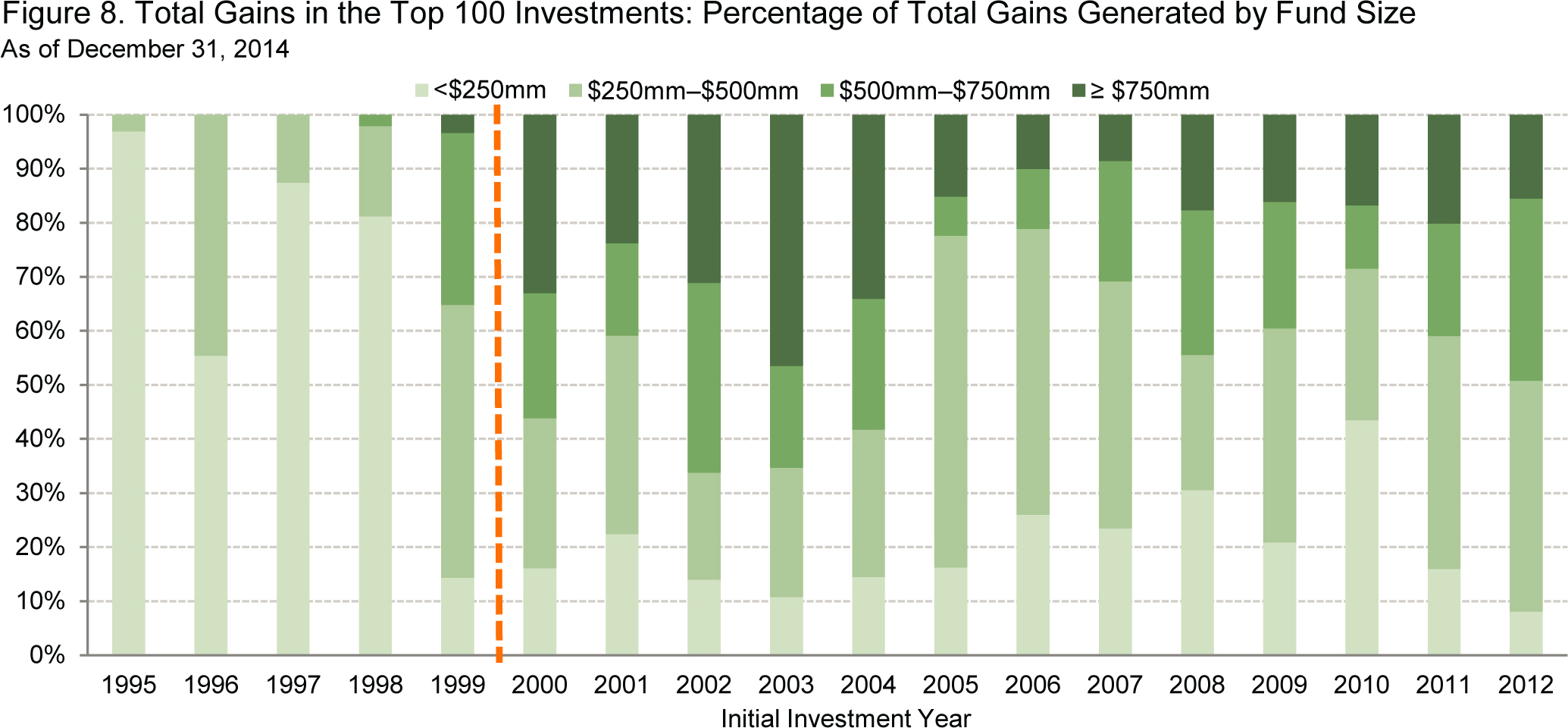

The VC gains vs. fund size according to Cambridge Associates

The VC gains vs. fund size according to Cambridge Associates

Cambridge Associates is not saying the VC world is doing OK, but that the increase in fund size has an impact on the investment dynamics. On the performance, the next figure (from another report) illustrates again the fact that performance may indeed be an issue…

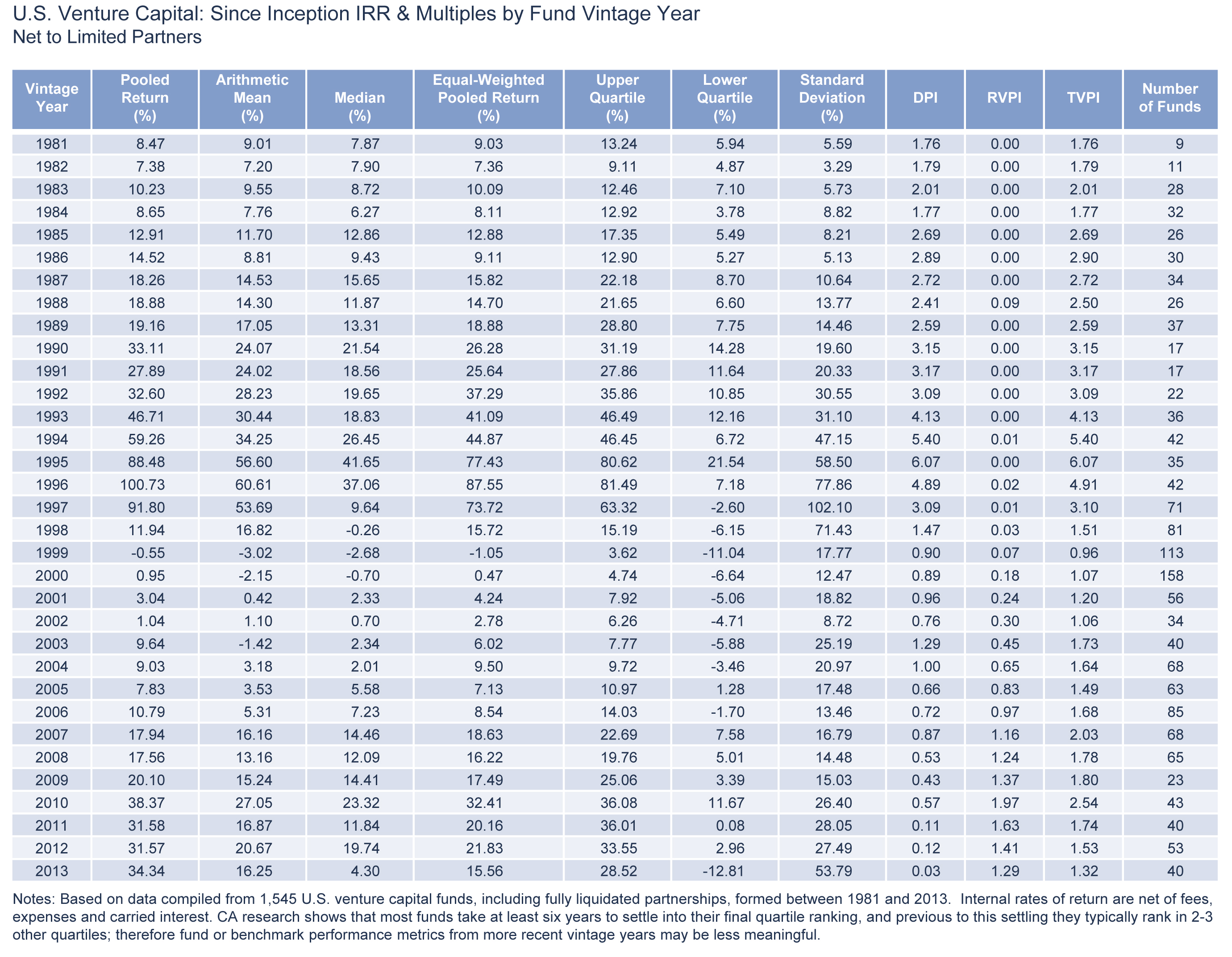

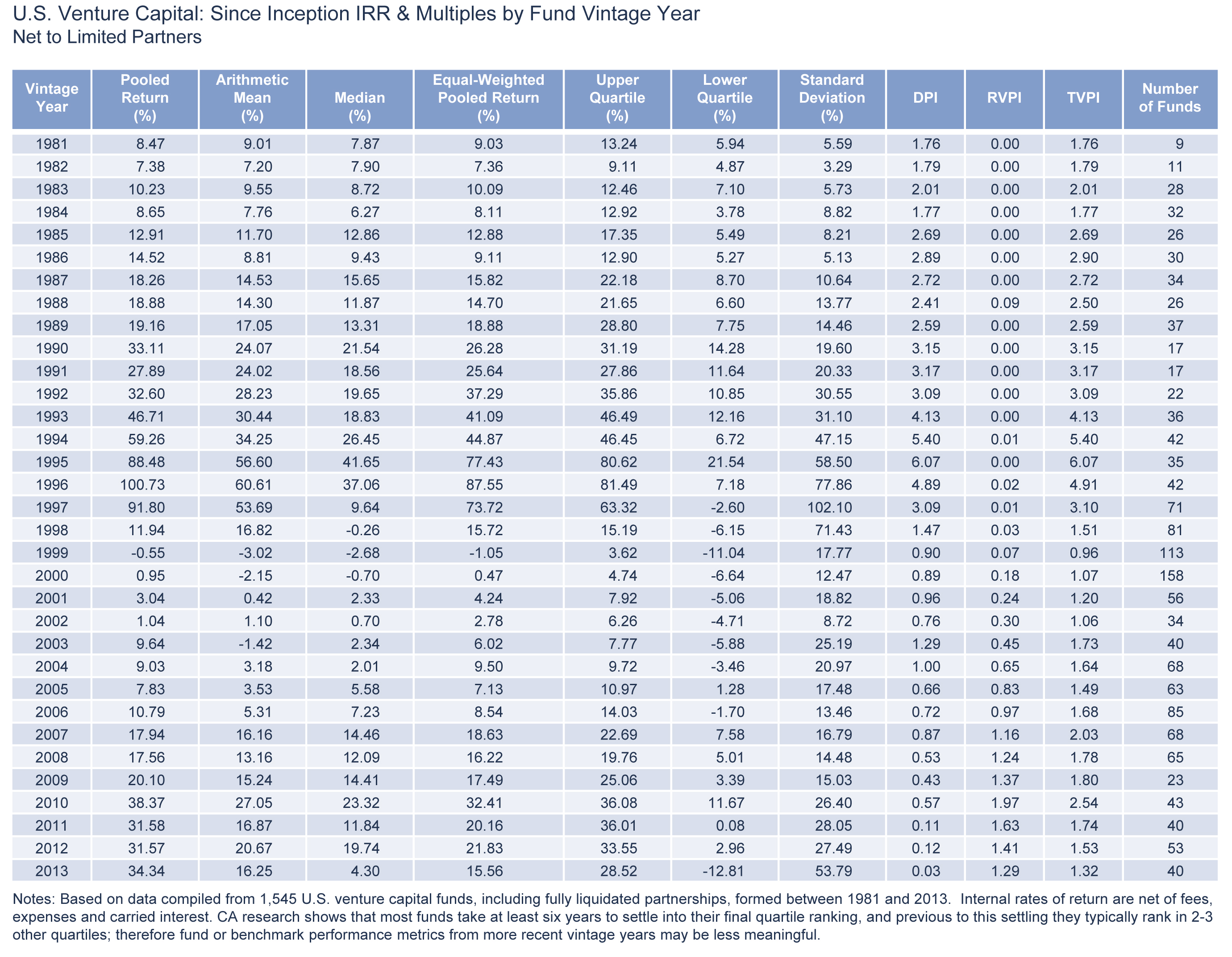

The VC performance according to Cambridge Associates

The VC performance according to Cambridge Associates

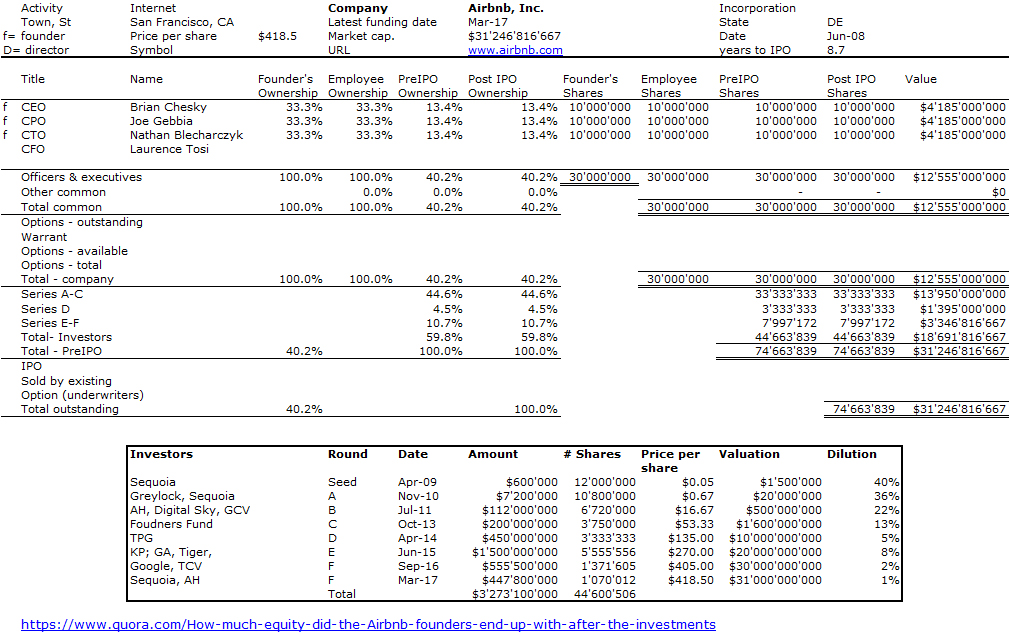

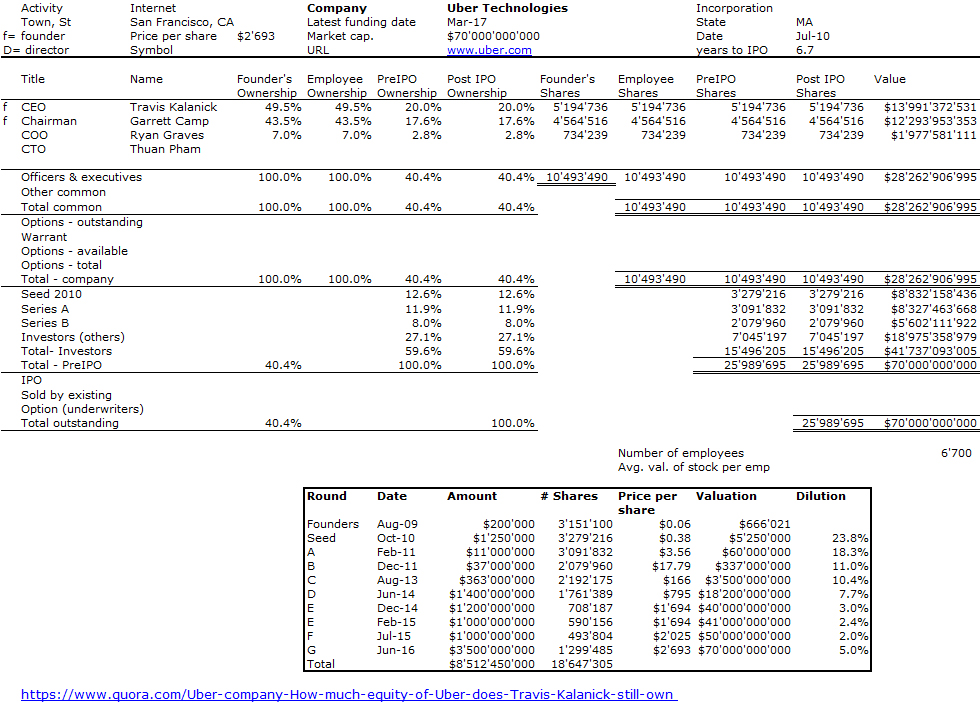

Bill Curley about unicorns

Bill Gurley is one of the top Silicon Valley VCs. So if he has something to say about the VC crisis, we should listen! No graph in his analysis, but a scary conclusion:

The reason we are all in this mess is because of the excessive amounts of capital that have poured into the VC-backed startup market. This glut of capital has led to (1) record high burn rates, likely 5-10x those of the 1999 timeframe, (2) most companies operating far, far away from profitability, (3) excessively intense competition driven by access to said capital, (4) delayed or non-existent liquidity for employees and investors, and (5) the aforementioned solicitous fundraising practices. More money will not solve any of these problems — it will only contribute to them. The healthiest thing that could possibly happen is a dramatic increase in the real cost of capital and a return to an appreciation for sound business execution.

The crowdinvesting report

So when I read Victoriya Salomon’s report about new financing platforms, I was intrigued. What does she say? “The global venture capital market suffers from unfavourable exit conditions reflected in a drop in the number of VC-backed IPOs and M&As. This trend affects all markets across all regions. In Europe, VC funds have shown less risk appetite by realigning their investment choices on later-stage companies and those already generating revenue. Furthermore, because of the poor performance of many VC funds during the six last years, they struggle to raise new funds, as institutional investors, disappointed by low returns, show a preference for the most successful large funds with a perfect track record. This slowdown particularly affects traditional venture capital investments, while, at the same time, the share of corporate venture capital has significantly increased, exceeding 15% of all venture capital investments by the end of 2012. In Switzerland, the venture capital market has also entered into a phase of decline and is losing ground in the financing of innovation. In fact, Swiss VC companies are suffering from a lack of investment capital and struggle to raise new funds. According to the Swiss Commission for Technology and Innovation, the amount of venture capital invested in Switzerland has shown a disturbing decline of about 40% during the last five years. [Also] venture capital investments in early stage start-ups fell by more than 50% from €161 billion in 2011 to €73 billion in 2012. In contrast, “later stage” participations grew by more than 50% in 2012 reaching €77 billion compared with €34 billion in 2011. While the number of early stage transactions is falling, investment periods are tending to become longer (7 years instead of 4-5) and the capital gain smaller.”

So the analysis is very similar. The VC world has experienced major transformations. The author believes that one solution might be the emergence of new platforms, such as crowdinvesting, which can be described as equity crowdfunding for start-ups. This is indeed an interesting argument. It is a way to scale and extend geographically the business angel activity. Now it could be also that we just need to go back to basics, i.e. less money with smaller funds, investing again like in the 80s and early 90s in less cash spending companies… Whatever the answer, the analysis seems consistent: the VC world has moved in a direction (fewer but bigger funds, in the USA mostly) which may not be good for a world where many more start-ups appear all over the world, not only in Silicon Valley, with relatively modest needs…

So what?

First if all this looked elliptic, not to say cryptic, you should read the reports and articles. They are excellent. Then, in a recent interview; I explained that money is needed, but (too much) money can be dangerous. That is I think the main message… you may read below if you want to have my views…

“A Good but Potentially Dangerous Idea”

Former venture capitalist, Hervé Lebret is now responsible for Innogrants (seed money) at EPFL.

What do you think of the proposal to create a future Swiss Fund?

This may be a good idea, but only under certain conditions. It must be able to hire talented managers because it is an extremely complex business. This is what Israel did when it established its venture capital funds, it brought in experienced American managers. Without the right people, it’s a recipe for disaster. And the fund must have the freedom to invest anywhere, not only in Switzerland. If you want a fund that only invests in Swiss start-ups, we may only create mediocrity.

Why?

Because no European fund can prosper by investing only in its own country. It’s a matter of scale. Only Silicon Valley has sufficient critical mass. The Californian model of venture capital is to lose money in most investments and make a few homeruns such as Google or Airbnb. So you need to have ten thousand ideas to create a thousand companies, then one hundred will grow, ten will be successful and one become Google or Airbnb. You must be able to create such a success every five years, and Switzerland just does not have the critical mass. And it is dangerous to focus too much on money.

Really?

Yes. Money is a necessary, but not sufficient for success. It requires funds, but also talent, a market, a product and ambition. It is not because we make money available to start-ups that success will come – the other ingredients should also be present. It is true that Switzerland lacks venture capital, but this is not what explains that Google, Apple and Amazon were not born here. This is in my opinion rather a cultural question. We lack ambition and rebellion. And this is the only factor that cannot be decreed by the authorities. Entrepreneurs are satisfied to aim at the creation of a viable firm of modest size, in which they retain control. In Switzerland, the start-ups create fewer jobs than McDonalds. Neil Rimer (note: co-founder of venture capital firm Index Ventures) wrote two years ago: “We and other European investors constantly are looking for world-class projects from Switzerland. I think there are too many projects lacking in ambition and supported artificially by organs – which also lack ambition – that give the feeling that there is sufficient entrepreneurial activity in Switzerland.” I have to agree with him.