Mazzacuto’s Entrepreneurial State is I think an important book. The author claims we have been unfair with the role in innovation of government and the public sector in general, which has provided funds for most not to say all R&D (Pharma, IT, Space). I share the blame as I am a strong supporter of start-ups, venture capital, Silicon Valley being the ultimate model. And the idea that the State should just provide the basics (education, research, infrastructure) and let the private sector innovate may have been a big mistake (of mine included). I will not take the blame on the second argument as I always shared with the author the idea that tax breaks and tax evasion makes the judgment even more unfair. Finally, the private sector is very risk averse so that there is less innovation (not only venture capital but corporate R&D, compared to the past when corporate R&D labs at IBM, Bell or Xerox were big or when VCs really contributed to innovation in semiconductor, computers and biotech in the 60s and 70s)

Let me now quote Mariana Mazzacuto following her book linearly. You can also listen to her when she gave a talk at TedX.

While innovation is not the State’s main role, illustrating its potential innovative and dynamic character – its historical ability, in some countries, to play an entrepreneurial role in society is perhaps the most effective way to defend its existence. (Page 1.)

Entrepreneurship is not (just) about start-ups, venture capital and “garage tinkerers”. It is about the willingness and ability of economic agents to take on risk and real Knightian* uncertainty, what is genuinely unknown. (Page 2.)

Note: *Knightian uncertainty relates to the “immeasurable“ risk, i.e. a risk that cannot be calculated.

Even during a boom most firms and banks (would) prefer to fund low-risk incremental innovations, waiting for the State to make its mark in more radical areas. (Page 7.) Examples are provided from the pharmaceutical industry – where the most revolutionary new drugs are produced mainly with public, not private funds. (Page 10.)

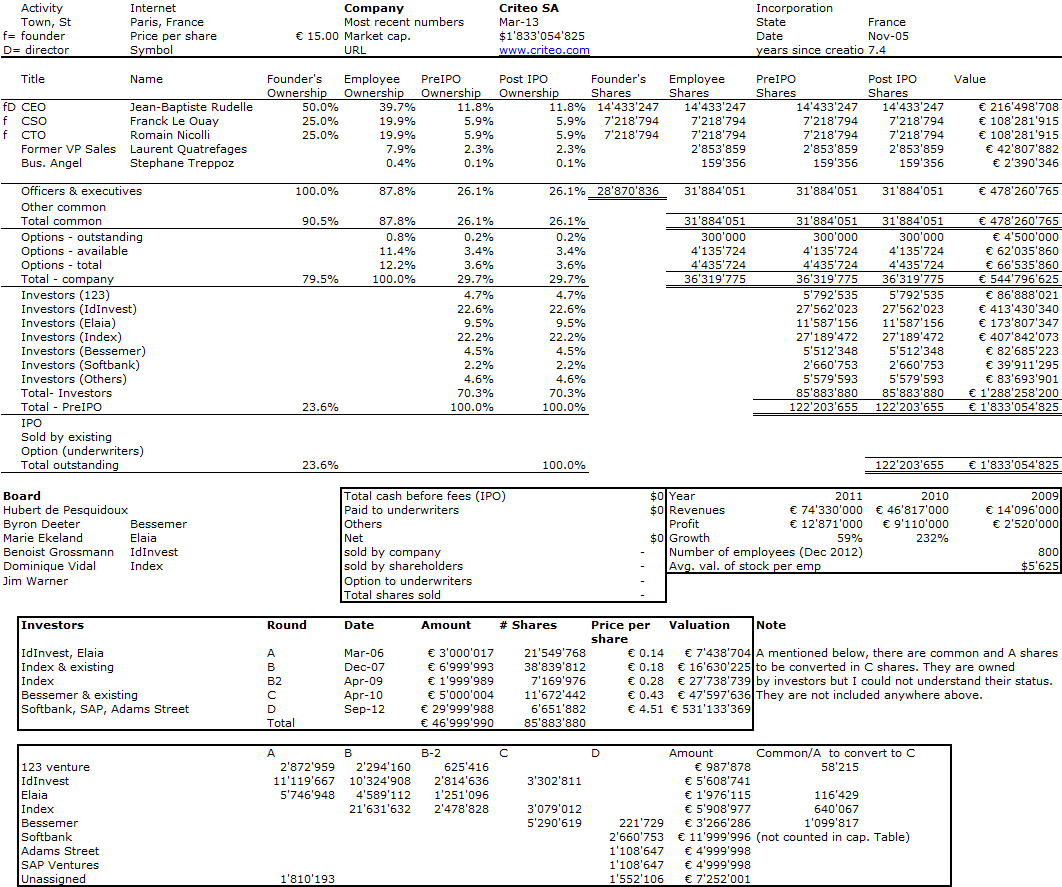

Apple must pay tax not only because it is the right thing to do, but because it is the epicenter of a company that requires the public purse to be large and risk-taking enough to continue making the investments that entrepreneurs like Jobs will later capitalize on. (Page 11) Precisely because State investments are uncertain, there is a high risk that they will fail. But when they are successful, it is naive and dangerous to allow all the rewards to be privatized. (Page 12)

Chapter 1 – (The Innovation Crisis)

The emphasis on the State as an entrepreneurial agent is not of course meant to deny the existence of private sector entrepreneurship activity, from the role of young new companies in providing the dynamism behind new sectors (e.g. Google) to the importance source of funding from private sources like venture capital. The key problem is that this is the only story that is usually told. (Page 20)

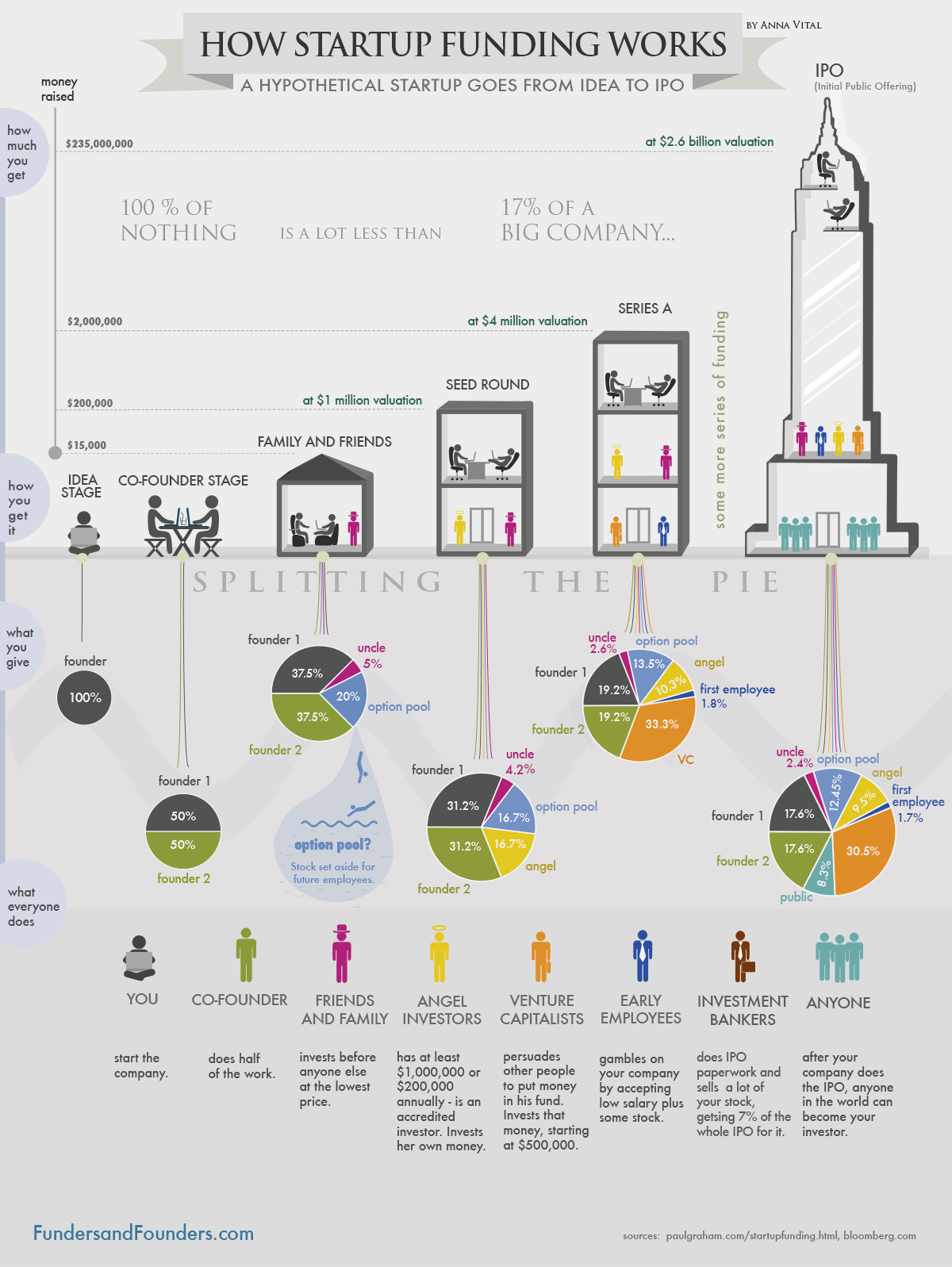

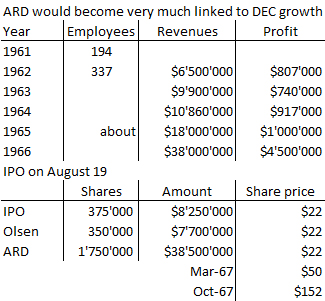

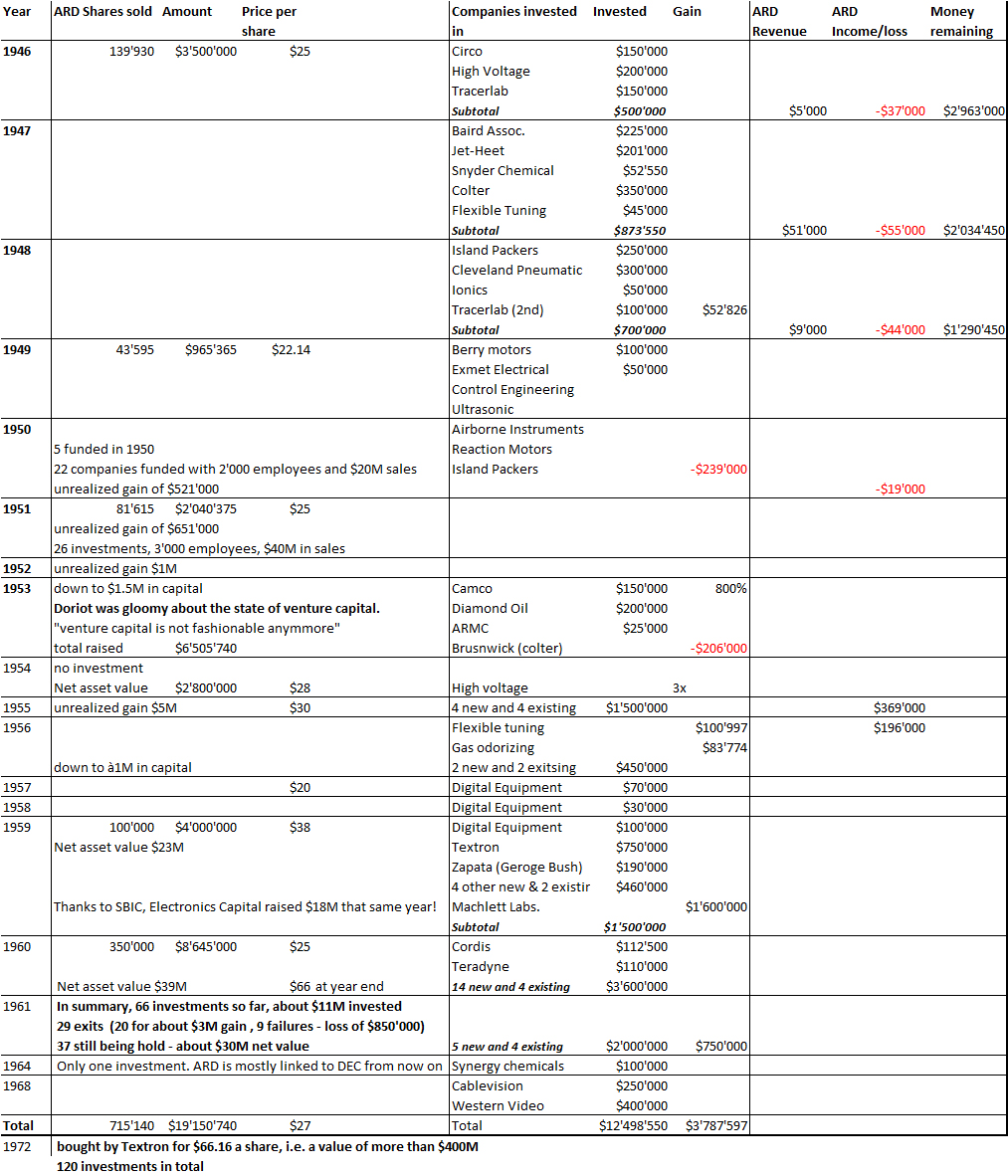

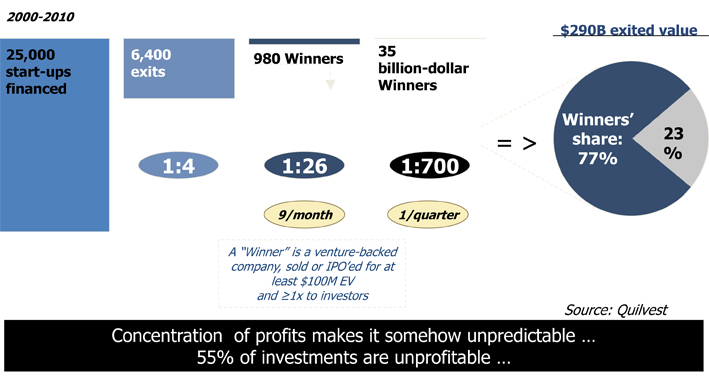

It is naive to expect venture capital to lead in the early and most risky stage of any new economic sector today** (such as clean technology). In biotechnology, nanotechnology and the Internet, venture capital arrived 15-20 years after the most important investments were made by public sector funds. (Page 23) The State has been behind most technological revolutions and periods of long-term growth. This is why an “entrepreneurial” state is needed to engage in risk taking and the creation of a new vision.

Note: ** Well maybe not in the 50s to the 70s, certainly in the last 10 years.

Big R&D labs have been closing and the R of the R&D spend has also been falling. A recent MIT study (1) claims that the current absence in the US of corporate labs like Xerox PARC (which produced the graphical user interface technology that led to both Apple’s and Windows’ operating systems) and Bell Labs – both highly co-financed by government agency budgets – is one of the reasons why the US innovation machine is under threat. (Page 24) Rodrik (2004) states that the problem is not in which types of tools (R&D, tax credits vs. subsidies) or which types of sectors to choose (steel vs. software), but how policy can foster self-discovery processes, which foster creativity and innovation – the need to foster exploration trial and error (and this is the core tenet of the “evolutionary theory of economic change” in chapter 2)

References

[1] MIT 2013. Innovation Economic Report, web.mit.edu/press/images/documents/pie-report.pdf

[2] Rodrik, 2004. Industrial Policy for the 21st century. CEPR Discussion Paper 4767

Chapter 2 – Technology, Innovation and Growth.

Progressive redistribution policies are fundamental, but they do not cause growth. Bringing together the lessons of Keynes and Schumpeter can make this happen. (Page 31) Solow discovered that 90 per cent of variation in economic output was not explained by capital and labor, he called the residual “technical change”. (Page 33)

An “evolutionary theory” explains this as a constant process of differentiation among firms, based on their ability to innovate. Selection does not always lead to “survival of the fittest” both due to the effects of increasing returns and also to the effects of policies. Selection dynamics in products markets and financial markets may be at odds.

Innovation is firm specific and highly uncertain. It is not the quantity of R&D, but how it is distributed throughout an economy. The old view that R&D can be modeled as a lottery where a certain amount will create a certain probability of successful innovation is criticized because in fact innovation would be an example of a true Knightian uncertainty, which cannot be modeled with a normal (or nay other) probability distribution. (Page 35 – the Black Swan again)

Systems of innovation are defined as the “network of institutions in the public and private sector whose activities and interactions initiate, import, modify and diffuse new technology”. (Equilibrium theory cannot work; rather than using incremental calculus from Newtonian physics, mathematics from biology are used, which can explicitly take into account heterogeneity, and the possibility of path dependency and multiple equilibria.) (Page 36) The perspective is neither micro nor macro, but meso. The causation between basic science, to large scale R&D, to applications to diffusing innovation is not linear, but full of feedback loops. One must be able to recognize serendipity and uncertainty that characterizes the innovation process. […] Using Japan as an example, “the contributions of the development state in Japan cannot be understood in abstraction from the growth of companies such as Toyota, Sony or Hitachi aside from the Japanese State’s public support for industry”. (Page 38)

Regional systems of innovation focus on the cultural geographical, and institutional proximity that creates and facilitate transactions between different socioeconomic actors, including local administrations, unions and family-owned companies… The State does this by rallying existing innovation networks or by facilitating the development of new ones that bring together a diverse group of stakeholders. But a rich system of innovation is not sufficient. The State must develop strategies for technological advance.

Mazzacuto finishes Chapter 2 with 6 myths about innovation I totally agree with!

Myth 1: Innovation is about R&D. “It is fundamental to identify the company-specific conditions that must be present to allow spending on R&D to positively affect growth.”

Myth 2: Small is Beautiful. “There is confusion between size and growth.” What is important is the “role of young high-growth firms. Many small firms are not high-growth. […] Most of the impact is from age.” “Targeting assistance to SMES through grants, soft loans and tax breaks will necessarily involve a high degree of waste. While this waste is a necessary gamble in the innovation process,” it should be targeted on high growth and not SMEs, i.e. support “young companies that have already demonstrated ambition”.

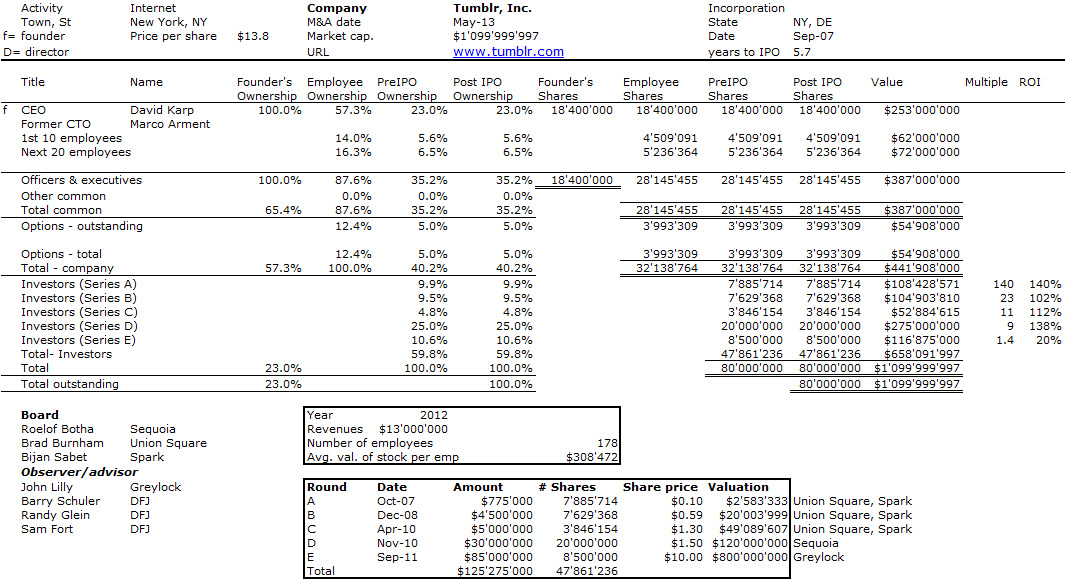

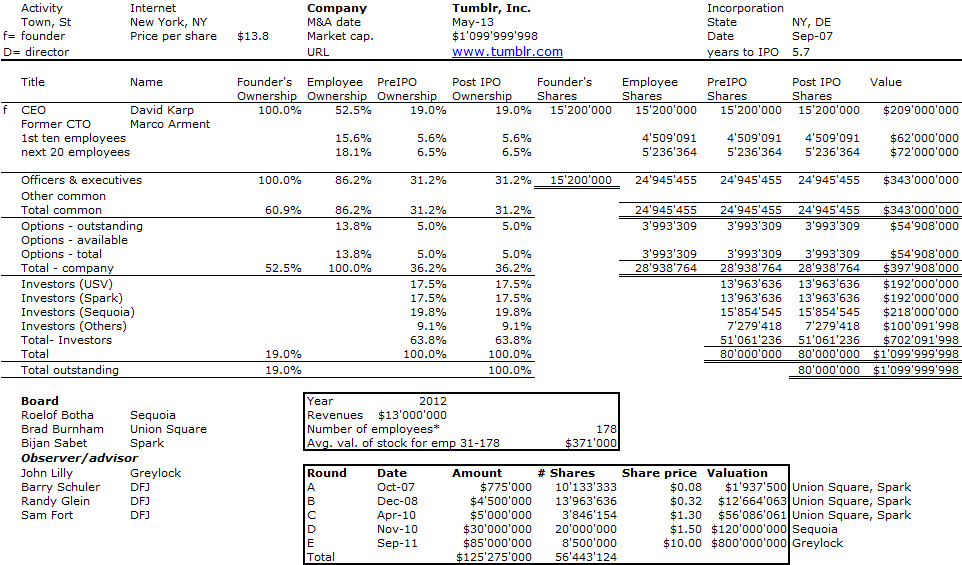

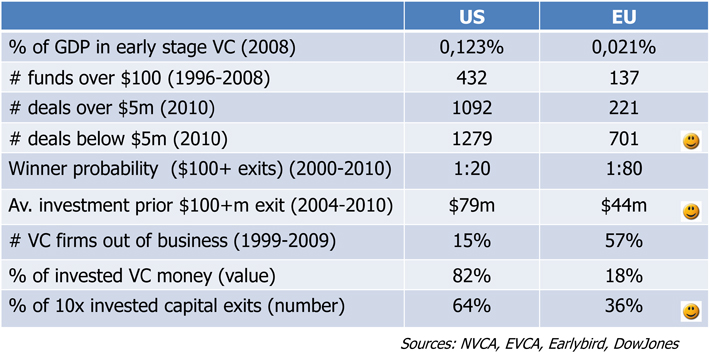

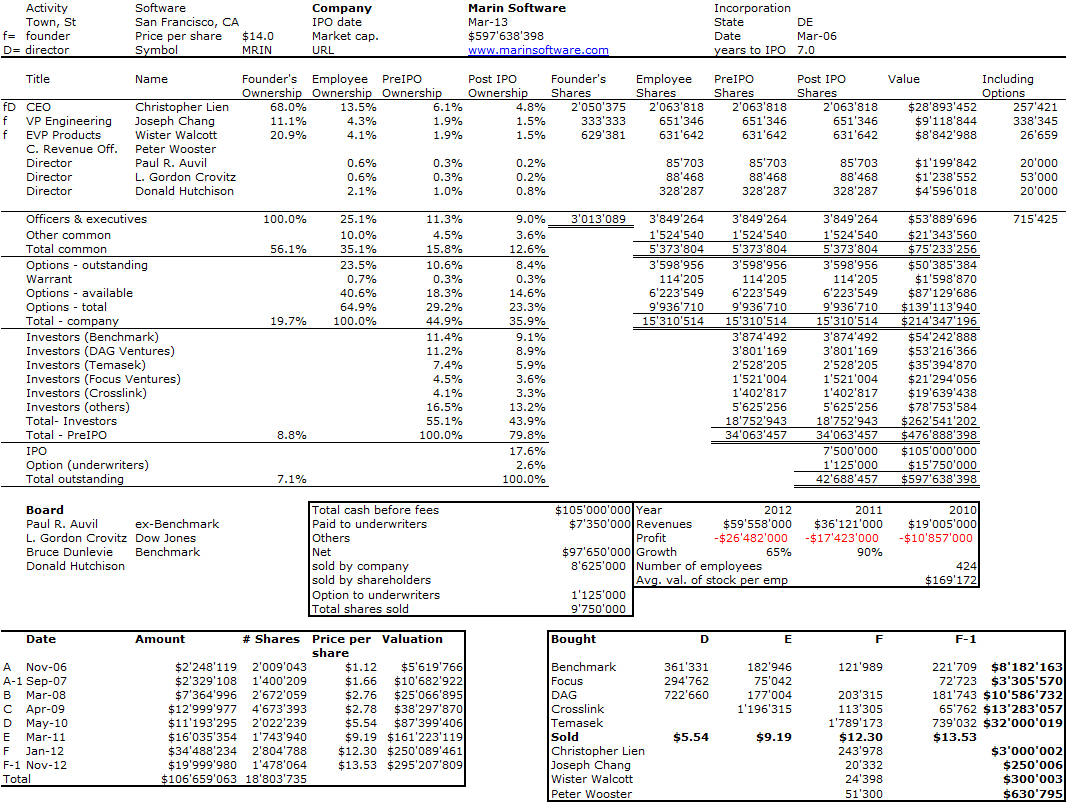

Myth 3: Venture Capital is Risk-Loving. “Risk capital is scarce in the seed stage; it is concentrated in areas of high-growth potential, low technological complexity and low capital intensity.” […] “The short-term bias is damaging to the scientific exploration process which requires longer-term horizon and tolerance to failure.” “Rewards to VC have been disproportional to risks taken”, but Mazzacuto also recognizes that “Venture capital has succeeded more in the US when it provided not only committed finance, but managerial expertise.” Finally “The progressive commercialization of science seems to be unproductive”.

Myth 4: Patents. “The rise in patents does not reflect a rise in innovation”. [I will not come back here on the topic, read again Against Intellectual Monopoly]

Myth 5: Europe’s problem is all about Commercialization. “If the US is better at innovation, it isn’t because university-industry links are better (they aren’t) or because US universities produce more spinouts (they don’t). It simply reflects more research being done in more institutions, which generate better technical skills in the workforce. US funding is split between research in universities and early stage technology development in firms. Europe has a weaker system of scientific research and weaker and less innovative companies.”

Myth 6: Business Requires Less Tax. “The R&D tax credit system does not hold firms accountable as whether they have conducted new innovation that would not otherwise have taken place, or simply pursued routine forms of product development.” “As Keynes emphasized, business investment is a function of the gut instinct of investors about future growth prospects.” This is impacted not by tax break, but by the quality of the science base, education, credit system and human capital. “It is important for innovation policy to resist the appeal of tax measures of different kinds”.

More will follow when I have read chapters 3 and followings. Now I need to share some of my concerns, first by quoting again:

“Entrepreneurship by the State can take on many forms. Four examples: DARPA, SBIR, the Orphan Drug Act, Nanotechnology. (…) Apple is far from the “market” example it is often used to depict. It is a company that not only received early stage finance from the government (through the SBIC program) but also “ingeniously” made use of publicly funded technology*** to create “smart” products.” (Pages 10-11)

Note: *** Internet, GPS, Touch screen, Siri.

“Many of the most innovative young companies in the US were funded not by private venture capital but by public venture capital, such as that provided by the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program.” (Page 20)

My concerns are that

– research is not innovation & the transfer is where entrepreneurship occurs so that investing in research is not innovating or even being entrepreneurial. This is at least my experience in the field.

– SBIR real impact unclear

– Green and nano-tech impact also unclear

But I have not finished reading yet…