I have finished reading Anthony Galluzzo’s book which I already mentioned in part 1 a few days ago. I hesitate between irritation and a more positive appreciation because I do not know if the author simply wants to undo the imaginaty of the region or to criticize its functioning more broadly. Indeed in the last two pages of his excellent book he writes: “After reading this book, some may wonder about the possibility of “undoing” the entrepreneurial imaginary; not only to deconstruct it, but to lead it to defeat”. Then he adds: “Many commentators have already noted this: to undo an economic and social system it is not enough to demystify the beliefs and refute the syllogisms conveyed by its ideology. It is also necessary to simultaneously think of another economy and another imaginary, to make other desirable representations and incarnations of human existence prosper.”

Silicon Valley as an ecosystem and its dark sides

I do not know what to think. An imaginary does not make a system, even if it is undoubtedly an important ingredient. Behind story telling and the myth of the heroic entrepreneur, there is an ecosystem that Galluzzo talks about more in the interview he gave to Echo (To understand the economy, you have to tell it through ecosystems, not trhough individuals – Pour comprendre l’économie, il faut la raconter par les écosystèmes, non par les individus) than in his book. Silicon Valley is an ecosystem and not (just) a myth factory to hide a darker situation [1].

Of course, there are dark sides in Silicon Valley. He shows it well in the beginning of his book, which I relate in my previous post, for example through the war for talents or the invisibilization of the State. His description is darker and darker in the end, even if the new elements are just as true:

– a glaring imbalance in the population of entrepreneurs with few women or African Americans,

– an under-representation of trade unions which would have deserved a more in-depth analysis,

– employees at the bottom of the ladder who are less well treated (assuming that these jobs have not been relocated),

– an unbalanced taxation [page 206] which would also have deserved a more in-depth analysis.

Galluzzo mentions tokenism as the reason for story telling. In the sociological literature, the practice of symbolically integrating minority groups to escape the charge of discrimination is called “tokenism” [Page 204]. Galluzzo also admits that there is not always story telling. Larry Page and Sergey Brin, the creators of Google are at the origin of one of the main powers of Silicon Valley and yet are relatively unknown to the general public. They have always been quite discreet, with rare and well-defined speeches. They did not invest in storytelling and personal branding [Page 218]. Nor does Galluzzo mention the thousands of unknown and often failed entrepreneurs who are a vital component of the region.

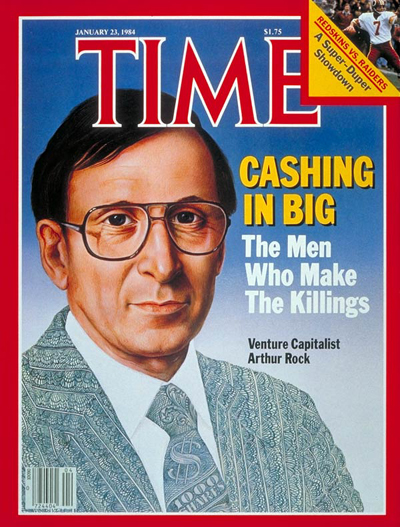

He adds that Silicon Valley would have flourished with almighty Thatcher neoliberalism. But it seems to me that he forgets that Silicon Valley really flourished in the two preceding decades, that of the 60s (Fairchild, Intel) which allowed the development of semiconductors and that of the 70s (Microsoft, Apple) for computers . He seems to forget, even if he mentions it, that without the structuring of venture capital in these two decades, but also without the arrival of highly qualified migrants in the decades that followed, there would probably be no such Silicon Valley such as it exists (and not as it is mythologized). I don’t think the subject is so “swept under the rug”. As early as the 1980s, a relatively mainstream author showed the darker sides of the region in his book Silicon Valley Fever. You can also read The Capital Sins of Silicon Valley.

What is an entrepreneur?

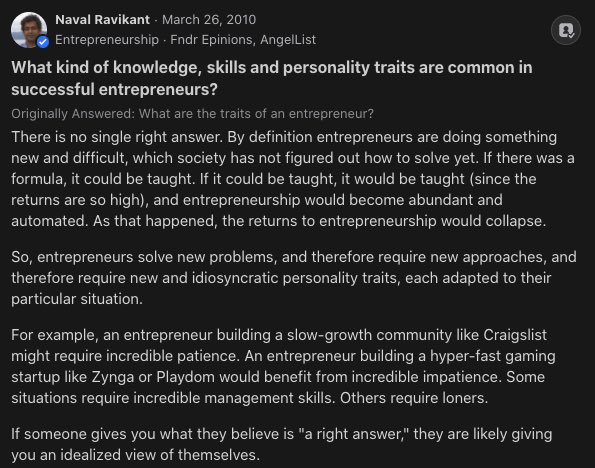

The pages [pages 196-98] on the definition or traits of an entrepreneur are also very interesting.

How to define the “entrepreneur”? A first approach consists in considering him simply as a business creator: someone who starts and organizes an economic activity. We mix the small craftsman and the big boss; the baker and the wealthy start-up founder. To focus on the latter, should we add to our definition an order of magnitude as to the economic success of the company and if so, which one? Should we limit the category to those who have founded a small business in hyper-growth? Another solution is to introduce the notion of risk. The entrepreneur would be the one who mobilizes resources in a situation of uncertainty; he would be the one who succeeds in his bets on the future. [Page 196]

Faced with these problems, it may seem essential to use the criterion of innovation. The entrepreneur would be the one who organizes a new combination of means of production: the one who develops a new product, develops a new method of production, creates a new market, conquers a new source of supply or disturbs the organization of a whole sector. […] However, defining the entrepreneur as an innovator requires de facto to separate innovation from the process, to extract it from the continuum, to attribute it, often very artificially, to a single actor. [page 197]

When research in entrepreneurship developed in the 1980s, it quickly focused on the questions of who was the particular personality of the entrepreneur. […] Among the traits that have been the subject of several studies, we note the propensity to risk, the tolerance for ambiguity, the need for accomplishment and the locus of internal control [the locus of internal control indicates the tendency that individuals have to consider that the events that affect them are the result of their actions] This research did not yield any conclusive results. [Page 198]

Galluzzo could have mentioned the definition of a startup given by Steve Blank which has been almost universally adopted, it gives a fairly convincing perimeter to the tech entrepreneur, the one in question here: “Start-ups are temporary entities looking for a scalable and repeatable business model.”

Finally on several occasions, Galluzzo seems to show his preference for the builder more than for the creator, Markkula rather than Jobs in the early days of Apple, Cook rather than Jobs in its last days: Bloomberg recently ranked all the CEOs in Apple history based on how the company’s valuation has evolved under their leadership; Steve Jobs (1997-2011, +12.4%) is far behind Mike Markkula (1981-1983, +64%) and John Sculley (1993-1993, +106%). Tim Cook outperforms them all with a +561% increase. I did not have access to the article and I could have been wrong but I arrive at different results for the growth rates from my multiples: Markkula, 4x in 2 years or 100%, Sculley around 1x or 0 %, Jobs (second period) 100x in 14 years or 40% and Cook, 10x in 12 years or 25%. Finally Jobs (1st period – in reality Scott) 1600x in 4 years or 500%. But this last subject is all the less important as I am not sure of all these figures. Founder, builder, storytelling and reality, these are subjects that remain fascinating. Thanks to Anthony Gazzullo for his excellent book and the thoughts it prompted me.

[1] Here are elements that describe an ecosystem and that I took from a post dated October 2015:

“5 needed ingredients of tech. clusters”

1. Universities and research centers of a very high caliber;

2. An industry of venture capital (i.e. financial institutions and private investors);

3. Experienced professionals in high tech;

4. Service providers such as lawyers, head hunters, public relations and marketing specialists, auditors, etc.

5. Last but not least, an intangible yet critical component: a pioneering spirit which encourages an entrepreneurial culture.

in “Understanding Silicon Valley, the Anatomy of an Entrepreneurial Region”, by M. Kenney, more precisely in chapter: “A Flexible Recycling” by S. Evans and H. Bahrami

Paul Graham in How to be Silicon Valley? “Few startups happen in Miami, for example, because although it’s full of rich people, it has few nerds. It’s not the kind of place nerds like. Whereas Pittsburgh has the opposite problem: plenty of nerds, but no rich people.” He also added about failed ecosystems: “I read occasionally about attempts to set up “technology parks” in other places, as if the active ingredient of Silicon Valley were the office space. An article about Sophia Antipolis bragged that companies there included Cisco, Compaq, IBM, NCR, and Nortel. Don’t the French realize these aren’t startups?”

Finally, entrepreneurial ecosystems need 3 ingredients – I quote:

– capital: by definition, no new business can be launched without money and relevant infrastructures (which consist of capital tied up in tangible assets);

– know-how: you need engineers, developers, designers, salespeople: all those whose skills are necessary for launching and growing innovative businesses;

– rebellion: an entrepreneur always challenges the status quo. If they wanted to play by the book, they would innovate within big, established companies, where they would be better paid and would have access to more resources.