A second post about the excellent Technocritiques – Du refus des machines à la contestation des technosciences after that one: Techno-critics according to François Jarrige. Jarrige surprises me by giving Gandhi‘s views on technology. Fascinating. I (in Fact Goodle translate was a great supporting tool…) translated his full account that you could read in French on pages 192-195.

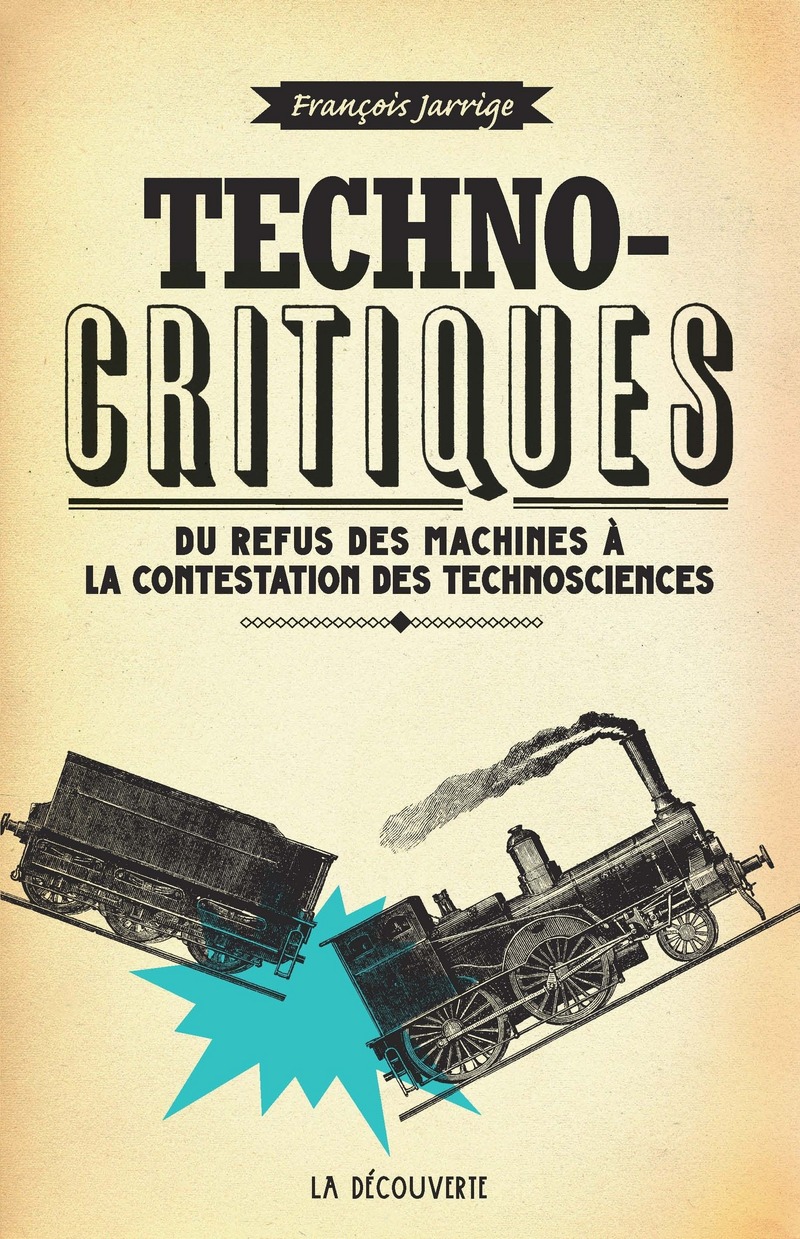

No one better illustrates the ambivalence of the relationship to technology in the colonial world than Gandhi. If indeed he uses a simple traditional spindle to weave his clothes, he travels by train and uses a watch. The figure of Gandhi deserves attention because criticism of the machine occupies a central place in his speech and action. But if his successors and followers have venerated him for his contribution to India’s political independence, they have rarely taken seriously his criticism of the technical surge and his proposal to restore the local indigenous economy. For Gandhi (1869-1958), the “machine civilization” and the big industry created a daily and invisible slavery that impoverished entire sections of the population despite the myth of global abundance. While some reduce Gandhian thought to a set of frustrated and simplistic principles, others see it as a rich “moral economy”, distinct from both the liberal tradition and Marxism [1].

Born in 1869 in the state of Gujarat, while British rule over India grew and the railway network expanded, Gandhi went to England to study law in 1888, like hundreds of young upper caste Indians. After 1893, he went to South Africa, where he thrived as a lawyer and woke up to politics in contact with racial discrimination. He gradually developed a method of non-violent civil disobedience that will make his celebrity and organize the struggle of the Indian community. On his return to India, after 1915, he organized the protest against the taxes considered too high, and more generally against the discriminations and the colonial laws. During the inter-war period, as a leader of the Indian National Congress, Gandhi led a campaign to help the poor, to liberate Indian women, to encourage fraternity among communities of different religions or ethnicities, for an end of untouchability and discrimination of castes, and for the economic self-sufficiency of the nation, but especially for Swaraj – the independence of India with respect to any foreign domination.

In 1909, Gandhi wrote one of his rare theoretical texts in the form of a Socratic dialogue with a young Indian revolutionary. This text, Hind Swaraj, written in Gujarati before being translated into English, aims first at detaching Indian youth from the most violent fringes of the nationalist movement [2]. The book was banned until 1919. According to Gandhi, these young revolutionaries are indeed the victims of a blind veneration of technical progress and brutal force imported from the Western world. He is therefore gradually extending his political criticism of the industrial and technological civilization itself. Gandhian thought is based on a sharp criticism of Western modernity in all its forms. On the political front, he criticizes the State and defends the ideal of a non-violent democratic society, made up of federated villages and based on the call for voluntary simplicity. He denounces the notions of development and civilization, and the technical surge that founds them, as sources of inequality and of multiple perverse effects. According to Gandhi, “the machine allows a small minority to live on the exploitation of the masses […] indeed the force that moves this minority is not humanity or the love of the like, but envy and greed “. Political autonomy is therefore futile if it is not accompanied by a profound questioning of modern industrial civilization. “It would be foolish,” says Gandhi, “to say that an Indian Rockefeller would be better than an American Rockefeller,” and “we do not have to look forward to the growth of the manufacturing industry.” Gandhi defends the development of self-sufficient local crafts within the framework of village autonomy and a limitation of needs.

Gandhi belongs neither to the Indian neotraditionalist currents that consider the ancient Hindu civilization as intrinsically superior, nor to the camp of the modernizing nationalists seeking to copy the Western world to turn its weapons against the colonial order. He intends to define a third original way. Gandhian thought feeds on multiple sources. In a way, it belongs to the anti-modernist current that developed in Europe at the end of the nineteenth century. He read William Morris and John Ruskin, and was marked by the anarchistic Christianity of Tolstoy [3]. His vision of the world feeds on the intellectual atmosphere of the end of the Victorian era and the ethical and aesthetic critique of the technical and industrial surge that was then developing. Gandhi is neither hostile to science nor anti-rationalist, as it is sometimes written. He first criticizes the way in which scientific discoveries and the use of reason are applied and put at the service of the powerful and exploitation. He criticizes the blind faith of the Western wolrd in material progress and the desire for power embodied in technical surge. He also wants to save England from its own demons. According to him, “mechanization has impoverished India”; it turns factory workers into “slaves”. It is not by “reproducing Manchester in India” that Indians will emancipate themselves from British rule. One of the particularly powerful technical bases of British rule is precisely the development of the railroad: “Without the railroads, the British could not have such a stranglehold on India. “Supposedly to liberate the Indian people, the rail is actually used primarily by the power as an effective tool of mesh and domination.” The railways have also increased the frequency of famines because, given the ease of transportation, people sell their grain and it is sent to the most expensive market” instead of being self-consumed or sold on the closest market. Gandhi tries to link his criticism of big industry and European technologies to his project of political emancipation. It shows that progress leads to a worsening of living conditions, that “civilization” permanently creates new needs that are impossible to satisfy, that it digs inequalities and immerses part of humanity in slavery. For him, this type of civilization is hopeless. The mechanization and globalization of trade is a disaster for India, the mills of Manchester having destroyed the craft industry and the world of Indian weavers: “The machinist civilization will not stop making victims. Its effects are deadly: people let themselves be attracted to it and burn themselves like butterflies in the flame of a candle. It breaks all ties with religion and in fact only derives tiny benefits from the world. [The machinist] Civilization flatters us to better drink our blood. When the effects of this civilization are fully known, we will realize that religious (traditional) superstition is harmless in comparison to that which nimbuses modern civilization.

Gandhian criticism of machinery intrigues much in the inter-war period. It is reflected in his economic program based on the defense of village industries as in its project to “de-mechanize the textile industry”, which appears immediately unrealistic and unrealizable. Moreover, Gandhi’s positions went from total opposition to European machines to a more nuanced criticism: in October 1924, to the question of a journalist, “Are you against all machines?” He replies: “How could I be … [I am] against indiscriminate craze for machines, and not machines as such”. He also rises against those who accuse him of wanting to “destroy all machines”: “My goal is not to destroy the machine but to impose limits on it”, that is to say to control its uses so that it does not affect the natural environments or the situation of the poorest. He ultimately develops a philosophy of limits and control of technological gigantism.

But this discourse provoked a lot of misunderstanding and was gradually erased as a reliquat of obscurantist tradition. The Socialists and with them Nehru himself in his autobiography published in 1936, lament that Gandhi “blessed the relics of the old order”. His analysis of industrial technology was soon marginalized to the independence of the country by the forced modernization project. But Gandhi’s figure also exerted considerable fascination far beyond the Indian peasantry. In the inter-war period, his criticism became a source of inspiration for social movements and thinkers from very different horizons, even as criticism of the “machine civilization” was growing in Europe.

[1] Kazuya Ishi, The socio-economic thoughts of Mahatma Gandhi as an origin of alternative development, Review of Social Economy, vol. LIX, 2001, p. 198 ; Majid Rahnema and Jean Robert, La Puissance des pauvres, Actes Sud, Arles, 2008.

[2] Hind Swaraj, translated in English as Indian Home Rule, and later in French with title Leur Civilisation et notre délivrance, Denoël, Paris, 1957.

[3] Ramin Jahanbegloo, Gandhi. Aux sources de la non-violence, Thoreau, Ruskin, Tolstoï, Editions du Felin, Paris, 1998.