So you want to be an entrepreneur, but you’re just not sure. And you wonder: Should I quit my well-paid job in the middle of a recession, raise money on 37 credit cards, build a lab bench in my garage next to my rusty old bike and start a […] company? Hell yes! Leaping into the void leads to freedom and growth, which always lands you on a higher plane. Afraid of failure? You’d be amazed at how many investors prefer to back someone who has tasted the bitter fruits of failure. In failing you learn what not to do. Get your skin in the game and there is no failure—you have opened your mind to growth and yourself to reinvention.

This is how Larry Marshall, a serial entrepreneur, begins an article he wrote in 2001! Maybe not as sexy as Guy Kawasaki or Paul Graham, but certainly as interesting. I just discovered this and his blog yesterday and I thought it is worth reading it entirely. So here is the full paper taken from Laser Focus World.

So you want to be an entrepreneur, but you’re just not sure. And you wonder: Should I quit my well-paid job in the middle of a recession, raise money on 37 credit cards, build a lab bench in my garage next to my rusty old bike and start a photonics company? Hell yes! Leaping into the void leads to freedom and growth, which always lands you on a higher plane. Afraid of failure? You’d be amazed at how many investors prefer to back someone who has tasted the bitter fruits of failure. In failing you learn what not to do. Get your skin in the game and there is no failure—you have opened your mind to growth and yourself to reinvention.

As engineers and scientists, we have natural obstacles to overcome if we are to become entrepreneurs. We look at things from the technology perspective and forget the mantra of the marketplace. Open your mind to a market, understand your customer’s problem, then create a solution that puts more cash in his pocket. While technology can enable a new business, it is not necessary. However, knowing your market and the needs of your customers is mission-critical in starting your business.

Too early to market and you run out of money before you generate revenue to sustain your business. Too late and you’re just another “me too” scrambling for the crumbs of the pie dropped by the market leader. But if you read the market right, then you ride the crest of the market wave all the way to success.

Focus, focus, focus

As a photonics person you should understand focus. In a startup your focus must be diffraction limited—do one thing and do it better than everyone else. With limited resources, the only way to produce enough force to penetrate the market is to focus all your weight on a single point. Don’t wear blinders. You must be aware of and respond to changes in the market. But focus is the key. Pick the one product you think will sell. Talk with your customers to define your product. Make sure that your customers want to buy it. Then, when you have defined it, engineer it, produce it, and sell it fast. Pick the wrong product and you will fail quickly. But try to spread the risk and you will linger in purgatory indefinitely.

Only two things create value in a company—product development and selling (marketing is selling to groups). Research may be the key to your company’s future, but there are bills to pay between now and then. Don’t get into business to do research—find a university and give them some money to do it for you; they’ll do a better job for less money. Your mission is to satisfy a market need and make money in the process. Unfortunately, it is possible to raise money today on the promise of tomorrow’s great technology, but this is a train wreck waiting to happen.

There is another aspect to focus—the customer. Everyone in the company from the janitor to the CEO must focus on the customer. Successful hi-tech companies maximize interactions between their engineers and customers and promote peer-to-peer selling. Customers are not only the source of your revenue, they are also the wellspring of your ideas.

One more thing, answer this question: Do I want to change the world (even a little), or do I just want to get rich quick? Those who start businesses because they want to create something new and better don’t always succeed, but those who are just in it for the buck almost never do. The fire inside your belly sustains you through the ordeal, but greed alone will not.

Did I mention focus?

Raising money

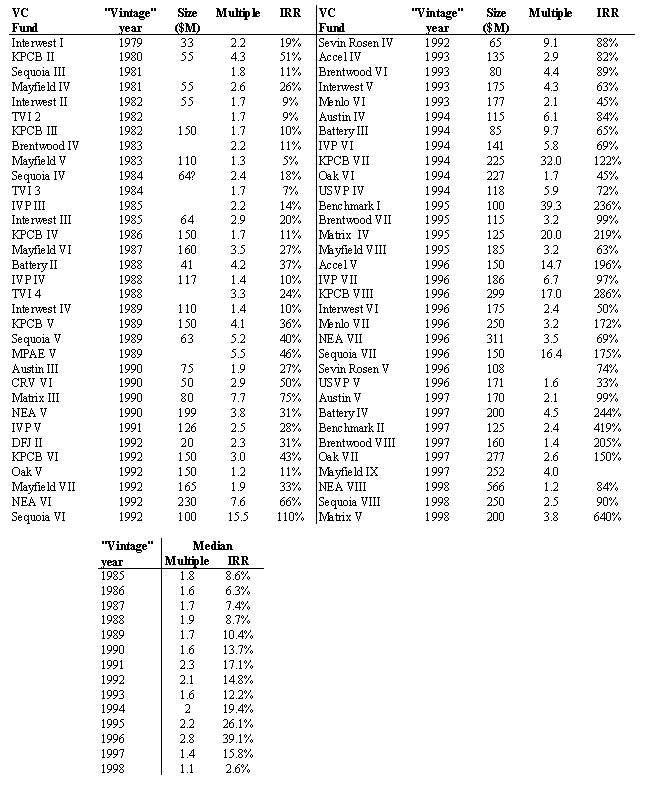

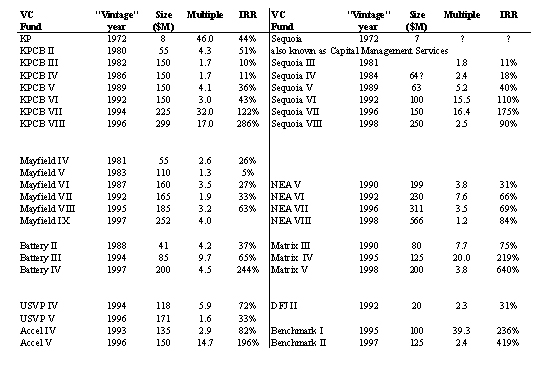

After funding startups in several ways, including using credit cards (37 of them, and in a recession too), friends and family, corporate backing, and venture capitalists (VCs), I have these observations. Bootstrapping and incubation work extremely well if you are smart enough to see far ahead of the market—then you can afford to trade time for money. You can raise an “angel” round to finance your prototype development and line up some real customers before you give away half the company raising venture financing. Although a VC will want 40% to 50% of the equity in the first round of financing (regardless of how much money you raise), if you can’t see more than two years into the future, get VC money (see “Making the pitch,” this page).

Venture capitalists add value beyond mere money. Their portfolio of companies can contain your future customers, their name should greatly leverage your cash, and their networks will open doors through which you could not otherwise pass. If you are a diamond in the rough, they will polish you until you shine, but if you don’t shine they’ll find another rock that will. And whoever gives you money, be it your brother, your barber, an angel, or a VC, make sure you like each other—you’ll go through a lot together in the years to come. Remember: you always need much more money than you think.

How do VCs decide which businesses to fund? Ask yourself how you decide to lend money to a friend. Trust. A VC trusts character, experience, team, and the quality of the idea. The idea will attract them, but the team will hook them. Venture capitalists invest in people first and ideas second. The market will change after you are funded and unless the team responds with better ideas, the business will fail. Startups have a wonderful ability to respond rapidly to change, and this, I believe, makes them the new-product development engines of industry.

Building the team

So what makes a great company? A great team. Clearly, a great CEO surrounds himself with people whose skills complement his own. Technical excellence alone is insufficient justification to hire any individual. It is better to have a well-coordinated team of good players than an ungainly group of outstanding individuals. As a founder you must set the tone for your company and recruit people who share your vision, goals, and ideals. Hire the best people you can find wherever you can find them. And always be on the lookout for your own replacement—after all, don’t you want the best people running your company?

When you start hiring skilled people, many of them will want to “make the move to management.” Few of them are capable. A great manager gathers information first, and then takes decisive action. A great inventor makes leaps of faith based on intuition, and is usually a frustrating manager. A great entrepreneur is a mix of the two. Understand that many people want to be managers but few should be—management is not about ego. It is about serving your subordinates in any way that better enables them to do their job, and then getting the hell out of the way so they can do it.

Even the best team players are working for a paycheck. So, share the wealth. Pay people what they are worth, not what you can get them for. Generally, compensate those who contribute to future value—scientists and engineers—in stock, and those who generate immediate value (sales) in cash. If everyone is an owner of your business they will take pride in it, nurture it, and ensure its success.

And remember, you are the lynchpin of your team. Surround yourself with quality advisors on technology, marketing, and business. These are peers, colleagues, and friends. But most important, find an experienced startup CEO who has built companies like yours before and who is still actively doing it, and make him your mentor.

Build more than a better mousetrap

As technologists we often are fooled into thinking that if we simply create a better technology, the market will be ours. A business creates solutions for which customers pay. So if better technology creates a better solution, then the world will beat a path to your door, right? Wrong! Technologically, visible diodes were a quantum leap from HeNe lasers, yet it has taken 10 years for them to replace the HeNe. It’s much harder than you think to displace an entrenched technology. You need substantial improvements, better cost structure, or both. Cash in the pocket is the customer’s bottom line—if you keep more in theirs, they will put some in yours. There is a fixed amount of cash being spent in any given industry. If you want a portion of that cash, either you can take market share from competitors, or capture cash that is paid to others (lifecycle costs, for example), or (ideally) grow the market by adding functionality. This is the crux of any new business.

In my second business, we created a revolutionary solid-state laser technology to replace the ion laser. We could produce several watts of green laser output from an all-solid-state box the size of a cigar case. This was a big improvement over ion lasers, but only to people who worried about 3-phase power, water-cooling, portability, and lifetime. It turned out that, for many people, other benefits of ion lasers that we had never considered outweighed these problems. We persevered, though, and ultimately found a niche in the medical market creating the world’s first miniature portable photocoagulator. Customers loved it. We also replaced copper vapor lasers in dermatology. Again the customers loved it. But we forgot to grow the market. We had made a box that didn’t need a new tube every few years. It worked so well, that once we sold a unit we never saw that customer again. Your new product should not only offer greater functionality at a lower price—it also needs to grow the market.

Running your business

The marketplace is a crucible that burns away all irrelevancies and leaves one pure product—profit. If you don’t make money, your business will fail, and no amount of excuses can save you. No excuses is a core principle of business. Keep your commitments! If you tell Wall Street you will make $1/share earnings—do it. If you fail, have a recovery plan and be sure to eliminate the source of the failure. The market hates failures, but it hates excuses more.

The market rewards results, not effort. As R&D people we learn there is no such thing as failure; even a null result is valuable. Not in business. If you spend a year working on a contract that then goes south, you just wasted a year. You failed to generate revenue and you took food out of the mouths of your team. You should be shot! I hope you had a backup plan.

As your company grows, it will change. Businesses tend to excel at only one thing, but that thing evolves over the life of a business. A typical cycle would be technology, then execution, then manufacturing. JDS Uniphase (JDSU; San Jose, CA) is a great example—it penetrated the market with a great technology, gaining knowledge and experience that enabled the company to execute better than everyone else, and ultimately developed a world-class automated manufacturing system that produce long-lived quality products at a lower price. Now JDSU has fine-tuned a process that allows it to buy new technologies and quickly integrate them into that finely tuned manufacturing machine—that’s an ability that’s hard to beat.

Are you the CEO?

I’ve been lucky enough to report directly to several different types of CEOs whose backgrounds were technical, sales, marketing, and engineering. The two best were technical and marketing. The latter person had a natural advantage over the others in that he valued technology for its ability to reach the customer, not as something of intrinsic worth. He was customer-focused and hired great technology people (I like to think I was one of them) to create his vision.

The technology person was a truly visionary CEO. He immersed himself in his customers’ market. He spent a lot of time working alongside his customers to understand their needs, and thereby won both their trust and their business. He understood their problems and solved them. If you can do this too, you will win! So what are you waiting for?

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I have been fortunate enough to learn from some outstanding people and I thank them here: Josh Mackower, Milton Chang, Ted Boutacoff, Don Hammond, Bill Lanfri, Walter Koechener, Paul Davis, Bob Anderson, Robert Haddad, Bob Byer, and Dan Hogan.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Larry Marshall is the CEO of Lightbit Corp, a next-generation telecommunications components startup. He has angel-invested in three startups, and personally done three others, including Light Solutions Corporation, which merged with Iris medical, and went public as Iridex, in February 1996 (Nasdaq:IRIX; Mountain View, CA). Marshall is an active inventor, holds nine patents protecting 16 commercial products, and has over 100 publications and presentations. He is chairman of the OSA Conference on Advanced Solid State Lasers, is an editorial advisory board member to Laser Focus World, and is on the board of directors of two telecommunications startups. Larry Marshall is founder and CEO of Lightbit Corp. P.O. Box 20453, Stanford, CA 94309; e-mail: larry@lightbit.com.

_______________________________

Making the pitch

When you write your business plan and pitch to a venture capitalist, you only need to answer seven basic questions:

- What problem or need will you solve or serve?

- Who are your customers?

- How much will they pay?

- What is your product?

- How much will it cost to build and sell?

- Who are your competitors and how will you beat them (barriers to entry or exit)?

- How big is the payoff and when will it happen?

Your single-page executive summary should answer these questions and is likely to be the only part of your plan an investor actually reads. Write concisely and honestly.

When you write your business plan remember that a little bit of “hype” goes a very long way—the wrong way. And don’t believe your own hype. If you claim, for example, that “there are no competitors” or that “they are inferior,” you are actually telling investors that you are either a genius or a fool (and they will assume the latter). It’s actually pretty easy to sell a story and there have been some great cons. But if you do sell a story you’ll spend the next several years building a business doomed to fail—and who wants to do that?

It is hard to be honest with your own ideas, so take them for a test drive with friends. Surround yourself with quality business advisors who are not afraid to tell you the truth and you can quickly separate the lemons from the gems.