This is my last post about Thiel’s class notes at Stanford and it is about Class 13 – Luck. Now I need to wait for his book to be published…

I love accidents. I mentioned it in a post which has nothing to do with start-ups (related to Street Art). The accident here is funny: I totally forgot to copy-paste Thiel’s class 13 and it is only when I began to read class 14 that I noticed my mistake. Now let me quote Thiel: “Note that this is class 13. We are not going to be like the people who build buildings without a 13th floor and superstitiously jump from class 12 to 14. Luck isn’t something to circumvent or be afraid of. So we have class 13. We’ll dominate luck.” Strange, right? I had to call this final part, part 7…

So what does Thiel say about luck? Well it is a debated topic, as I experienced in my activity at EPFL. Thiel feels the same. He begins with: “The biggest philosophical question underlying startups is how much luck is involved when they succeed. As important as the luck vs. skill question is, however, it’s very hard to get a good handle on. Statistical tools are meaningless if you have a sample size of one. It would be great if you could run experiments. Start Facebook 1,000 times under identical conditions. If it works 1,000 out of 1,000 times, you’d conclude it was skill. If it worked just 1 time, you’d conclude it was just luck. But obviously these experiments are impossible.” adding the famous Thomas Jefferson’s line: “I’m a great believer in luck, and I find the harder I work the more I have of it.”

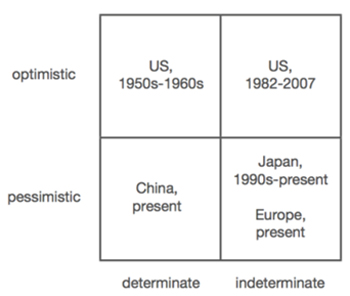

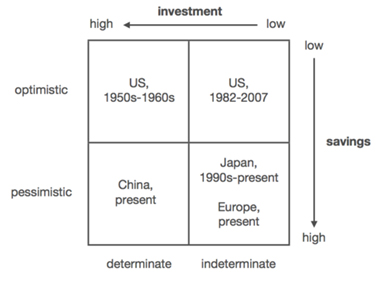

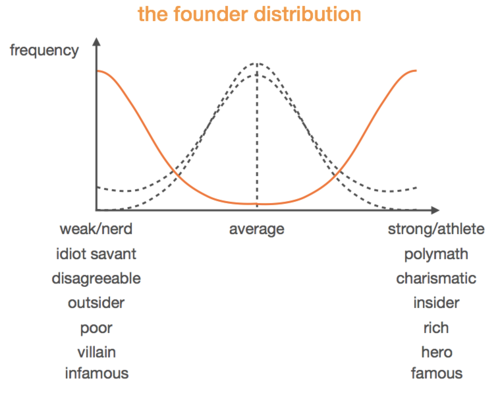

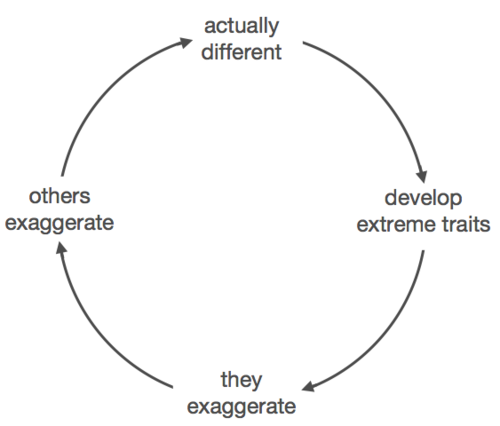

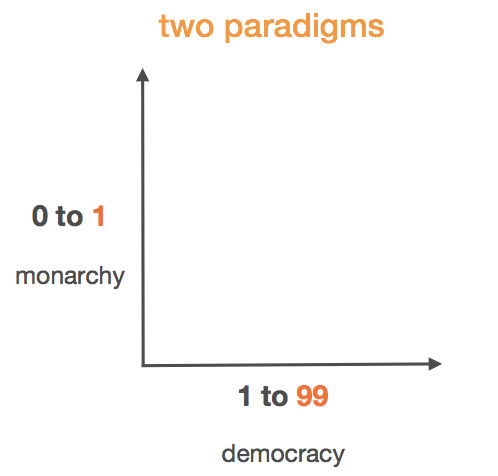

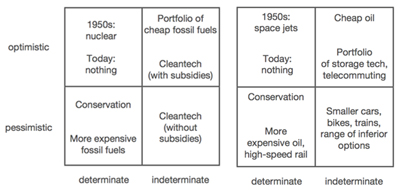

Thiel is not so much interested in luck as in determinism vs. indeterminism. “If you believe that the future is fundamentally indeterminate, you would stress diversification. […]. If the future is determinate, it makes much more sense to have firm convictions. […] Overlay this diversification/conviction dynamic over the optimism/pessimism question and you get further refinement. Whether you look forward to the future or are afraid of it ends up making a big difference. And here is his vision of the world:

With an even more surprising and quite convincing:

“But the indeterminate future is somehow one in which probability and statistics are the dominant modality for making sense of the world. Bell curves and random walks define what the future is going to look like. The standard pedagogical argument is that high schools should get rid of calculus and replace it with statistics, which is really important and actually useful. There has been a powerful shift toward the idea that statistical ways of thinking are going to drive the future.”

But here I’d love to ask Peter Thiel what he makes of Black Swans if he believes in 0 to 1 more than in 1 to n. 1 to n belongs to statistics, not 0 to 1… (read again my part 1 if this is cryptic)

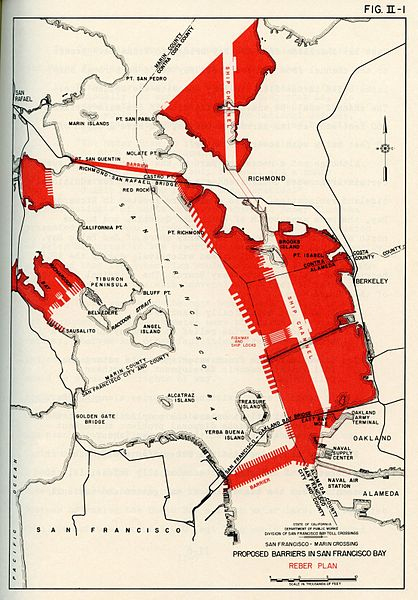

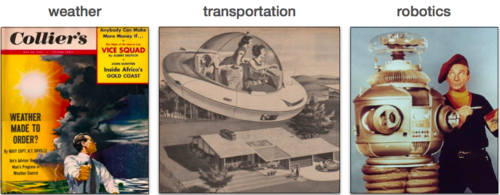

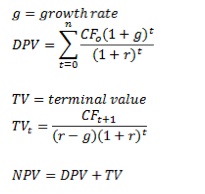

Thiel likes crazy ideas, like Reber’s project for the Bay Area in the 1940s above. He also still believes in finance despite its excesses: “In a future of definite optimism, you get underwater cities and cities in space. In a world of indefinite optimism, you get finance. The contrast couldn’t be starker. The big idea in finance is that the stock market is fundamentally random. It’s all Brownian motion. All you can know is that you can’t know anything. It’s all a matter of diversification. There are clever ways to combine various investments to get higher returns and lower risk, but you can only push out the efficient frontier a bit. You can’t know anything substantive about any specific business. But it’s still optimistic; finance doesn’t work if you’re pessimistic. You have to assume you’re going to make money. […] Indeterminacy has reoriented people’s ideas about investing. Whereas before investors actually had ideas, today they focus on managing risk. Venture capital has fallen victim to this too. Instead of being about well-formed ideas about future, the big question today is how can you get access to good deals. In theory at least, VC should have very little in common with such a statistical approach to the future.“

And he might agree with Mariana Mazzucato during his debate to come with her (at Human After All, Toronto 2014 – program in pdf) : “The size of government hasn’t changed all that much in the last 40-50 years. But what the government actually does has changed radically. In the past, the government would get behind specific ideas and execute them. Think the space program. Today, the government doesn’t do as many specific things. Mainly it just shifts money around from some people to other people. What do you do about poverty? Well, we don’t know. So let’s just give people money, hope it helps, and let them figure it out.”

Darwinism and design.

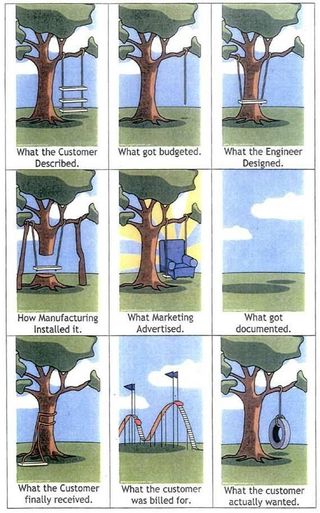

And all of a sudden, while reading this class 13, Thiel again surprises me! Obviously, the indeterminate optimism can be quite easily linked to Darwin’s theory of evolution. Accidents happen, but there is general positive evolution. And “Applied to start-ups, obsession with indeterminacy leads to the following phenomena:

• Darwinistic A/B testing

• Iterative processes

• Machine learning

• No thinking about the future

• Short time horizons”

Typical Blank’s messages! But Thiel envisages another possibility: “Apple is absolute antithesis of finance. It does deliberate design on every level. There is the obvious product design piece. The corporate strategy is well defined. There are definite, multi-year plans. Things are methodically rolled out.” (I do not think Thiel talks here about intelligent design which is opposed to Darwinian theory, but the coincidence is a little puzzling!

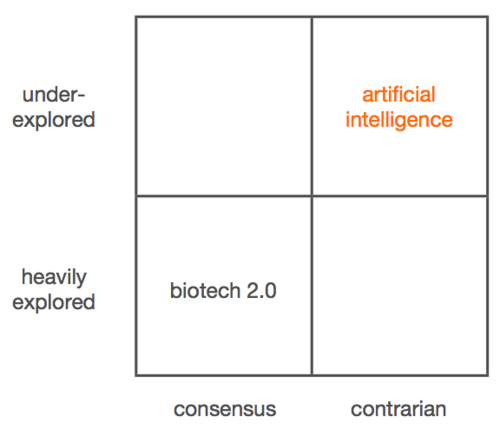

“On the heels of Apple has come the theme of well-designed products being really important. Airbnb, Pinterest, Dropbox, and Path all have a very anti-statistical feel. […] That link—great design—seems to work better and faster than Darwinistic A/B testing or iteratively searching through an incredibly large search space. The return of design is a large part of the countercurrent going against the dominating ethos of indeterminacy. Related to this is the observation that companies with really good plans typically do not sell. If your startup gets traction, people make offers to buy it. In an indefinite world, you will take the money and sell, because money is what you want. […] But when companies have definite plans, those plans tend to anchor decisions not to sell.[..] In an indefinite world, investors will value secret plans at zero. But in a determinate world, robustness of the secret plan is one of the most important metrics […] It’s important to note that you can always form a definite plan even in the most indefinite of worlds. […] We’re falling downwards towards pessimism. Can we shift instead to definite optimism?”

This is the end of my notes on Thiel’s great vision about start-ups.