Here is my latest contribution to Entreprise Romande. I return to a subject that is dear to me, Innovation and Society. (If you read French, the original version is certainly better…)

The Enterprise is more than ever at the core of the political debates through its role in the creation of jobs and wealth – both individual and collective. It is indirectly the source of populism and of protectionist temptations. Inside and outside of its walls, innovation is the subject of similar tensions: are the returns and benefits of innovation sufficient for society?

Mariana Mazzucato and the Entrepreneurial State

A recent book tackles the topic of the respective roles of business and government in innovation: Mariana Mazzucato, a professor at the University of Sussex, develops in The Entrepreneurial State [1] – a fascinating and quasi-militant book – the argument that the States have not collected the fruits not only of direct investments in their universities, and even indirectly from the help and support provided to businesses, investments and supports that are at the origin of the major innovations of the last fifty years.

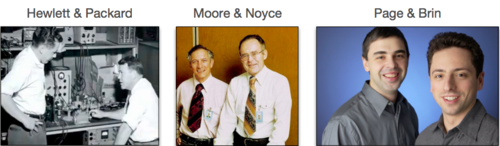

Mazzucato brilliantly illustrates this through the example of the iPhone and the iPad, which integrate components initially financed by the public bodies: from electronics developed for the space and military programs to the touch screen or GPS, or even Siri, the voice recognition tool (which has sources at EPFL), the author shows that Apple has masterfully integrated technologies initiated by public money. Google is also the result of research done at StanfordUniversity. Mazzucato adds that clinical trials for new drugs are mainly made in hospitals funded by public money, from molecules equally discovered in university laboratories.

Mazzucato therefore advocates major reforms both on the governance of the initial support and on taxation. She fights for a new tax system that would compensate the absence or insufficiency of direct returns to universities or from businesses, all the more that it is indeed undeniable that multinational companies easily optimize their taxation. She shows how Apple has taken advantage of international rules to create subsidiaries in Nevada or Ireland to minimize its taxes.

The English researcher is convincingly claiming that Apple has to pay more. But how to pay? Paying a license for the GPS, but to whom? I’m not even sure that the GPS is patented. And if the Internet had been patented, it would probably not have had the same development – I do not ned to go over the limitations of the French Minitel. By seeking more direct financial returns (which are not as insignificant as one might think – Stanford has received more than $300M for its equity shares in Google and over $200M of the first patents in biotechnology), the risk would be very high to discourage creators and stifle innovation. I doubt that the solution lies in more rigorous national rules.

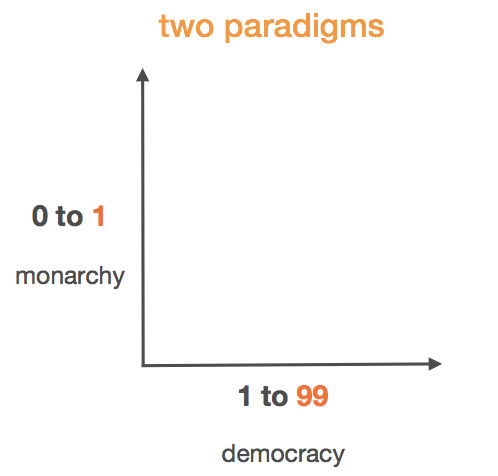

Peter Thiel and the Individual Entrepreneur

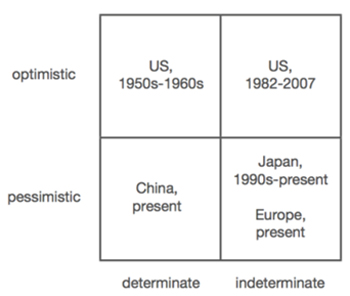

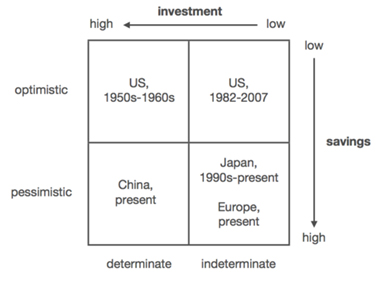

Peter Thiel, an libertarian entrepreneur and investor, is so opposed to such views that he encourages youung people motivated in entrepreneurship to abandon their studies by providing them with $ 100,000 grants and he even imagines moving businesses to offshore vessels off California so they totally escape tax. He is afraid of any form of public support which, he considers, quickly becomes bureaucratic. It is worth adding that Thiel’s motto also shows his skepticism about the social benefits of innovation: “We wanted flying cars; instead we got 140 characters.” [2]

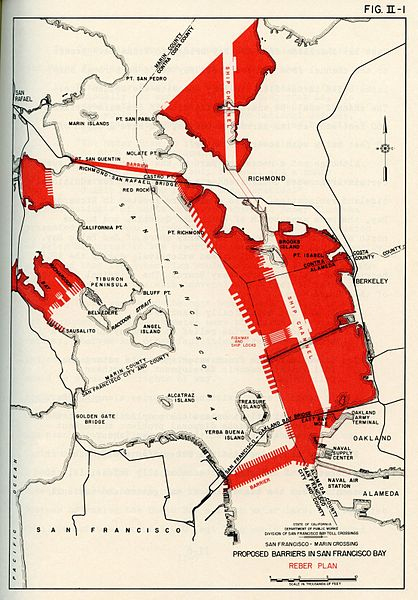

Upstream, there is therefore the question of direct returns and the actual role of the state. But without the incredible creativity of Steve Jobs at Apple, without the extraordinary ambition of Larry Page and Sergei Brin at Google, without the vision of Bob Swanson, a co-founder of Genentech, the world would probably not have experienced the same technological revolutions. Downstream, the question arises of how to create international rules on innovation. Let me make a wide digression. The Internet, another innovation initiated by public authorities, has become a major topic in the political, economic and fiscal fields. But “neutrality and self-organization are part of the libertarian options […] and are inconsistent with politics. Humanity must seize this opportunity to revisit what is considered important. […] The Internet enables the emergence of a global political space, but it is still to be invented. At the time of this invention, the Internet will probably be gone!” [3]

If from experience I lean more toward Thiel’s view on innovation as an individual act of exception, actually quite far from the public investment, even if it is its seed, yet, I cannot agree with abandoning the public good. It is the soil that allows the emergence of exceptional talent. Companies also have their share of responsibility in discounting the importance of the collectivity. Just like in any complex human activity, innovation is a delicate balance between private and public actors. But especially today, issues have become global. The question is not so much as Mazzucato says that the role of the state has been largely underestimated in this process, but rather that the tax return has largely been decreased by globalization and the lack of economic governance.

Tax as a single global solution?

Does society receive any return from the public money spent on schools, roads, security? No, because it’s not an investment in the true sense of an objective of financial gain. These are infrastructure provisions that allow citizens and businesses to exist and develop properly. And they 8should) pay taxes in return. When Darpa funds Stanford, it is not sure that a student from Korea will not benefit from it and later work for Samsung. The concept of supporting national champions seems of another age.

We are left with Tax, in a renewed vision of its global governance. Whether innovation is in the public or private domain, the world globalization will soon prevent from hiding behind the argument of whom is basically at its origin. Not only individuals but states also must agree upom a greater share of its profits, at the risk of serious crises. At a time when Switzerland reviews its tax policy and its citizens think they can create barriers from its neighbors as its borders, it is important to be aware that the current tensions are an opportunity to revisit the status of innovation in society before new major crises emerge. Wishful thinking?

[1] The Entrepreneurial State – Debunking Public vs. Private Sector Myths. 2013, Anthem Press, http://marianamazzucato.com

[2] Peter Thiel. Zero to One – Notes on Startups or How to Build the Future. Sept. 2014, Crown Business press, http://zerotoonebook.com

[3] Boris Beaude. Les fins d’Internet. 2014, FYP Editions, http://www.beaude.net/ie