If you do not know Edouard Bugnion, you can read the article I had published in 2010, a Swiss in Silicon Valley. Edouard was at EPFL last week and gave a great technical talk about VMWare and virtualization, in fact a summary of his PhD thesis. The full text comes below.

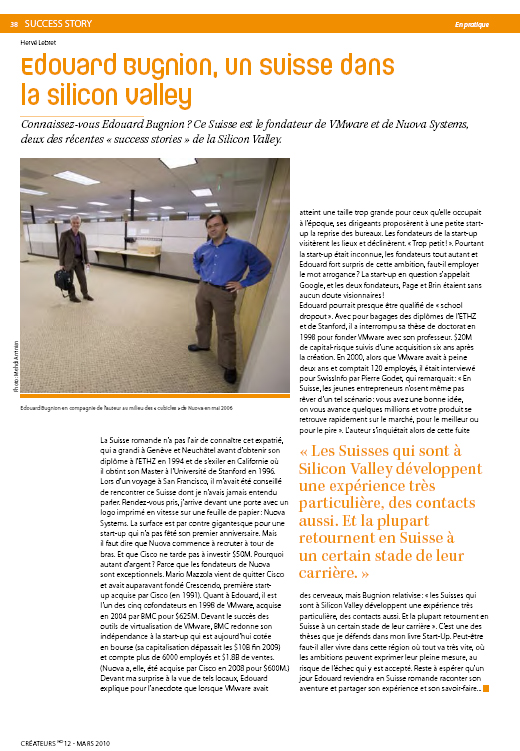

Edouard Bugnion with the author in the middle of « cubicles » at Nuova in May 2006 (Picture: Mehdi Aminian).

For the anecdote, you can notice than Ed began his PhD in 1994 and will only finish it in 2012! As Martin Vetterli, dean of Computer Science at EPFL, said “at least he is finishing it, contrarily to the Yahoo or Google founders!”. The reason why it took Ed so much time is that he co-founded VMWare and Nuova in between… I have such a friend from Stanford who was doing his MS / early PhD in 1990-92 and obtained finally his diploma in 2004. He also had his start-up journey in the middle. (Faster though, Michael!) This back and forth adventures are not very common in Europe…

I noticed 2 other great lessons from Ed’s talk:

– as mentioned below “Virtual machines quickly lost popularity with the increased sophistication of operating systems” and it did not prevent VM to become a great market through VMWare success. Market dynamics are never simple and great opportunities may come from less explored areas of technology.

– Ed also explained that they did not or could not partner with established players (microprocessors or OS vendors) for various reasons. You can imagine the big players did not care, or would not change / adapt their (strategic) products or features. So when Ed was asked if this was not risky, he answered, risk is (sometimes) good.

Once again, this proves first that SV success comes also from immigrants and second, we need these people and their experience back! Hopefully we will have him at our ventureideas conferences. Invitation launched!

EPFL IC Seminar : “Using Virtual Machines in Modern Computing Environments with Limited Architectural Support”

By Edouard Bugnion, Stanford University

Abstract

Virtualization has gone through a full “popularity cycle”. Originally conceived in the mainframe era, virtual machines provided an efficient, isolated, and compatible duplicate of the hardware of the underlying machine. Virtual machines quickly lost popularity with the increased sophistication of operating systems, and subsequent processor architectures were designed without consideration for virtualization.

In this talk, I propose to use virtual machines to address limitations of commodity operating systems on modern architectures, even in the absence of architectural support for virtualization in the hardware. The primary technical contributions of the work were developed as part of two systems, each built for platforms with limited architectural support for virtualization. First, Disco ran commodity operating systems on scalable MIPS multiprocessors. Disco enabled virtual machines to form a virtual cluster that could transparently share the resources of the underlying multiprocessor. Second, VMware Workstation is a successful commercial product that allows multiple, unmodified operating systems to run concurrently on the same x86 system, allowing users to decouple their guest operating systems from the underlying hardware. VMware Workstation was the first 32-bit virtual machine monitor for the x86 architecture, and demonstrated that the x86 architecture was indeed virtualizable, despite a lack of architectural support.

Today, and in part because of the impact of Disco and VMware, virtual machines once again play a foundational role in Information Technology, and current-generation hardware provides architectural support for virtualization, similar to what already existed decades ago on mainframes.

Biography

Edouard Bugnion started his Ph.D. at Stanford in 1994, and is expecting to finish it this month. In the meantime, he co-founded two successful companies: VMware and Nuova Systems (acquired by Cisco). At VMware from 1998 until 2005, he served multiple roles including CTO. At Nuova/Cisco from 2005 until 2011, he built the core software team and became the VP/CTO of Cisco’s Server, Access, and Virtualization Technology Group, a group that brought to market Cisco’s Unified Computing System platform for virtualized datacenters.

His research interests include computer systems, datacenter and cloud networking, as well as technology entrepreneurship. For their work, Bugnion and his colleagues have received the ACM Software System Award (for VMware) and the ACM SIGOPS Hall of Fame Award (for Disco). Edouard was raised in Neuchatel, Geneva, and graduated from ETHZ.