As indicated in my previous article, I preferred to cut out my summary of the workshop on the subject “Deeptech: are we ready to scale?” organized by Inria during the Vivatech trade fair

If the first round table spoke about bipeds, the second was about ecosystems, about “rain forests” more than “French gardens”!

Antonin Bergeaud, I listened to you when you received the award for the best young economist in France, particularly about technological innovation, on France Inter and France Culture and you said at one point that you were drawing a parallel between your childhood dream of being an astronomer and your situation as an economist by saying that you wanted to understand the complexity of the world but that in the economy, there is the human factor which there is not with the stars. Is that our challenge or are there other elements that interest you so that we have European Gafam tomorrow?

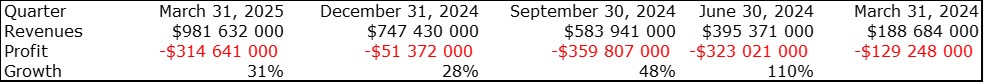

“We have the impression that the level of complexity is really in hard sciences but in the human sciences there are a lot of interactions that make things very complicated and in particular because we have little regularity so we have to deal with the fact that there are biases. Like what was mentioned that in Europe we are less enthusiastic than the Americans, but we don’t know how to measure this very well. There are a lot of features that we have to take into account and since the challenge is to try to inform and shed light on why we have such difficulties, for example having a Tech sector that is of the same magnitude as the one we have in the United States or why companies have difficulty obtaining financing in Europe, we are obliged to take into account all these dimensions and it is true that it is quite complicated, so that is a bit where the parallel ends, it is that it is complicated. I think that now there is a kind of consensus beginning on the structural difficulties that we have in France and in Europe, which does not mean that we are going to correct them but at least we are beginning to understand a little better what is happening.” […]

– we don’t have enough entrepreneurs and we don’t have enough engineers trained in France and Europe […] there’s a real training issue that needs to be addressed, largely because you have a lot of losses, a lot of entrepreneurs and engineers leaving for the other side of the Atlantic.

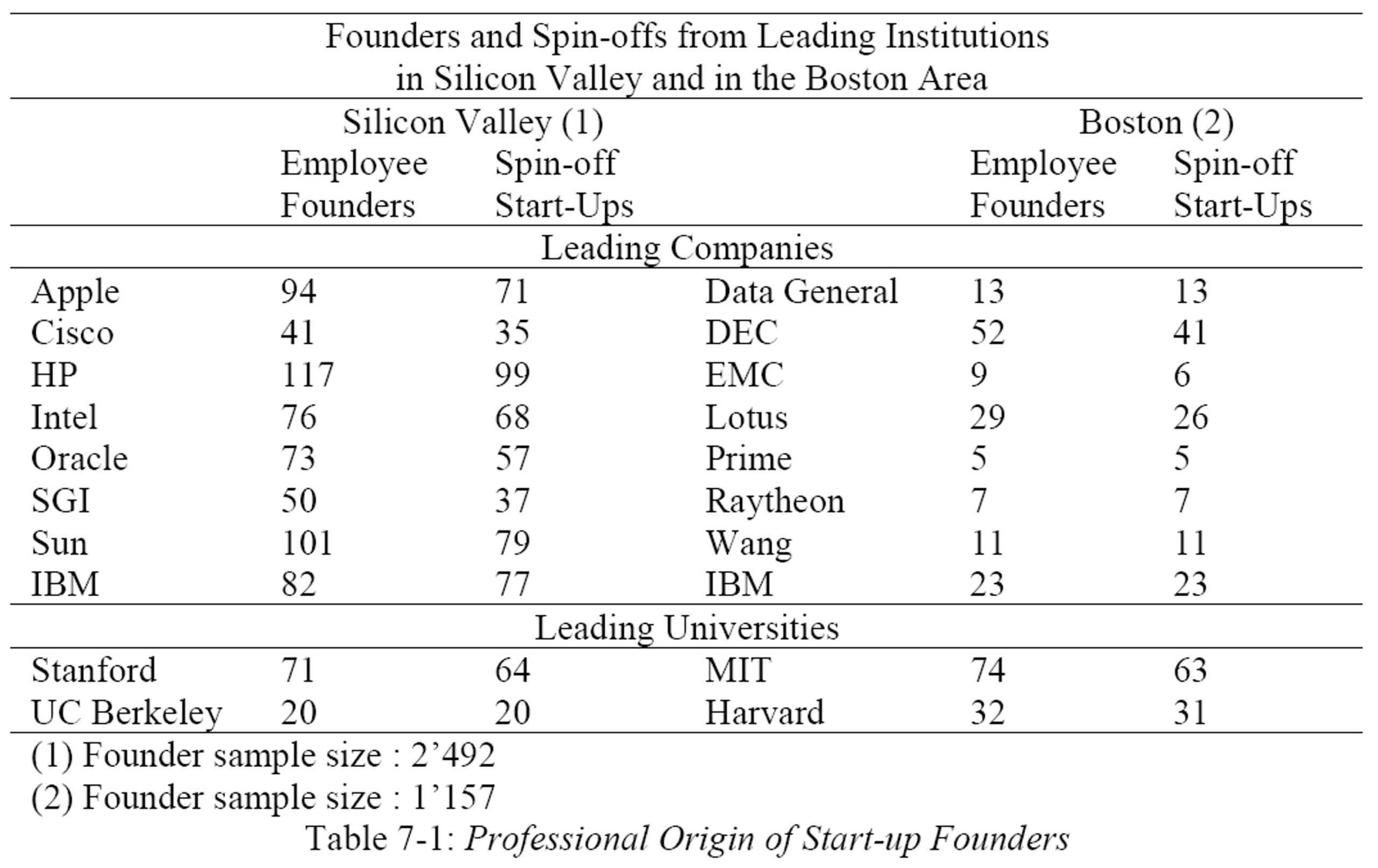

– the second difficulty in Europe, because all the French problems are quite real everywhere in Europe, is getting universities to connect with businesses. For example, all patents filed by all companies in the world must provide the academic references they use in the patent description, and what we see is that for certain technologies, where Europe is practically non-existent in terms of technology production and marketing, we are actually relatively dominant or at the same level as the United States in the production of ideas, except that these ideas are not cited by French or European patents; they are cited by Chinese or American patents. So, basically, we have scientists and researchers who produce very relevant ideas, including on very, very recent technologies, and ideas are supposed to circulate freely. They circulate freely, but they circulate a lot from Europe to other countries, and a little less in the other direction.

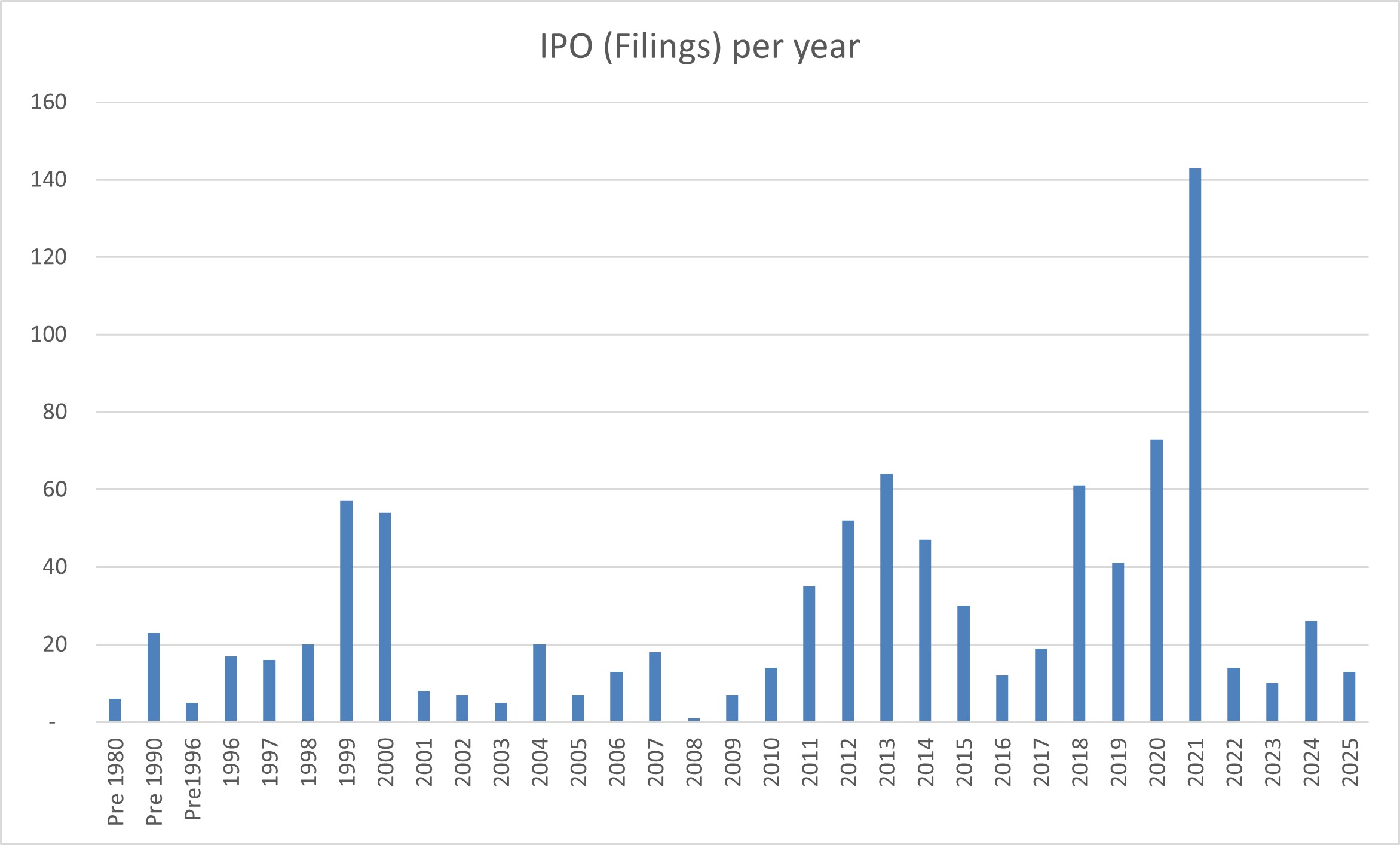

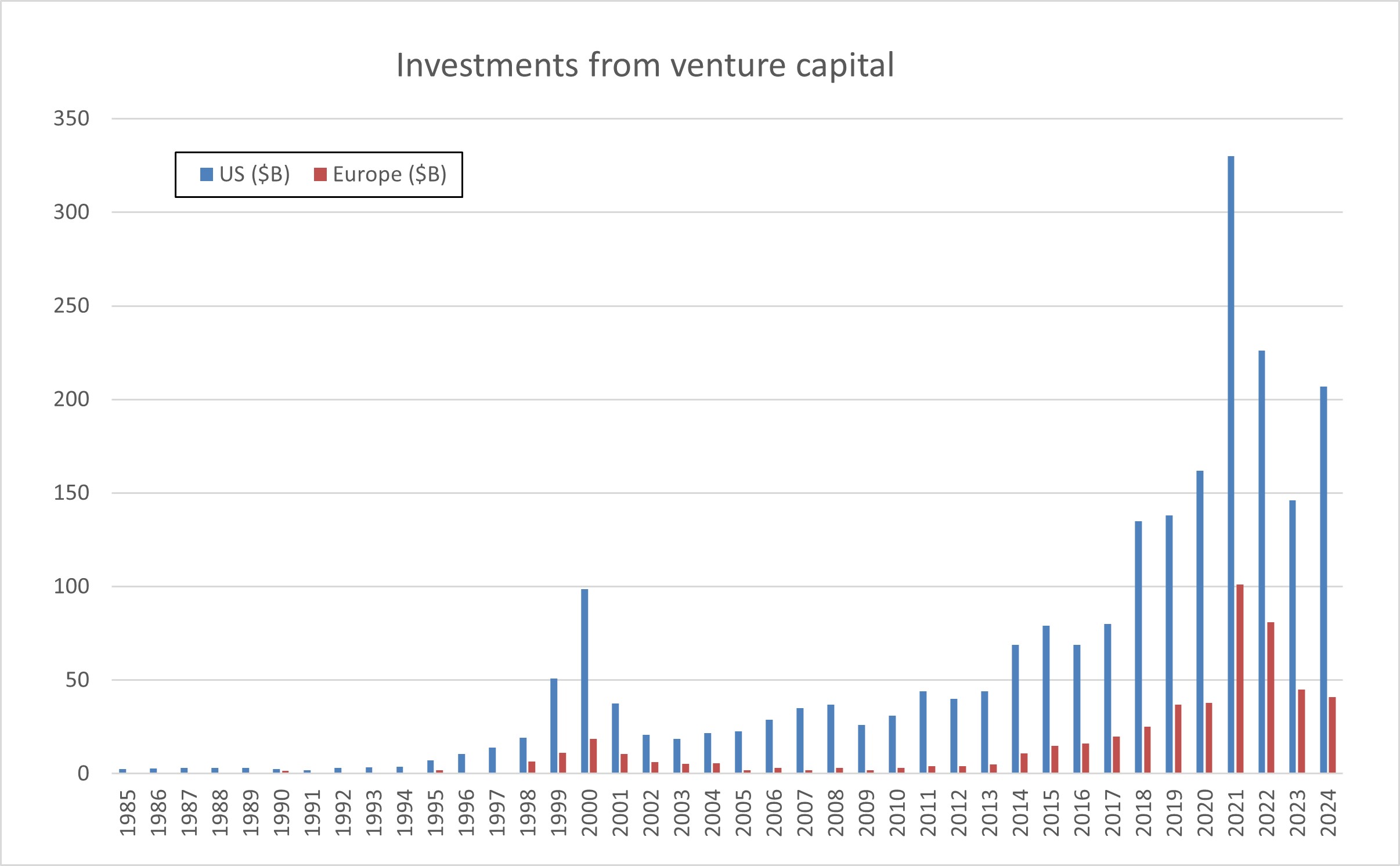

– the third problem is indeed financing, which was discussed a lot earlier. I think that in Europe we have a relationship with risk that is really specific to our continent. Perhaps it is not necessarily negative, and I don’t think we should necessarily give it up, but we must be aware that it poses a certain number of difficulties in growing companies quickly, particularly in disruptive technologies, because we tend to move more towards bank financing, because we have less venture capital funding, because we have a market that is very fragmented, particularly in terms of financing innovation, and because we have institutions and regulations that are much more restrictive, at least from a growth point of view, than what is done in the United States.

Paul Midy, I could call you Mr. Start-Up at the National Assembly. What would you like to add?

“I would put the issue of financing number 1 by far. Fundraising in Europe seems to be three times lower than fundraising in the United States, even though we are generally roughly the same size, we generate roughly the same GDP. When you put your money into a company like Mistral, a deeptech company, you don’t get it back the following year, it’s at least 20 years later that you get it back; it’s long-term capital. And this long-term capital exists mainly in retirement capital, and so I would say that the number 1 factor is the fact that we have a pension system in France, and many in Europe too, which is a pay-as-you-go system that is not a capitalization system. We don’t have pension funds or we have very few. We have to realize the enormous gaps that this generates in France. Long-term savings and what can look a bit like capitalization are 200-300 billion euros; if I take the whole European Union, it’s 6,000 billion and essentially it’s the democracies of northern Europe at 70%; if I take the United States it’s 42,000 billion. You can supply a New York Stock Exchange with 25,000 billion and supply a Nasdaq with 25,000 billion and on the other side in France you have Paris the Paris Stock Exchange 3,000 billion Frankfurt 3,000 billion London 3,000 billion so we have a stock of capital which is much less important and so for fundraising the result of all this is that our start-ups last year raised 50 billion in the United States it’s 150 billion. […] I call for us to make a CIP, a common innovation policy at least as ambitious as the CAP, the common agricultural policy. A third of the budget of the European budget is the CAP. Another third is the social cohesion funds. Very important. Innovation is less than 10% of Europe’s budget. It must at least be three times more immediately. […] I am a politician, so we are trying to change the system. Either we say to ourselves, it’s a culture, that’s how Europeans are, and they like risk less, they are a little more grumpy and everything, and so there is nothing to be done. I can’t accept that, so I’m trying to understand why the Americans are in a different situation; it’s not genetic. I think we need to set ourselves the goal of making Europe the richest, most prosperous continent in the world, therefore the most innovative, capable of defending itself, and then everything will flow from that.

Alexis Robert, you work for Kima Ventures, which is Xavier Niel’s fund, whose recent book “Une sacrée envie de foutre le bordel” (A Real Desire to Cause Trouble) I read, and which sometimes puts himself at odds with the system. Do you also, by working for the Kima Ventures fund, have a slightly more atypical view of these things, or how do you want to build on what we just shared?

“In fact, what happens when you are early stage, while what you mentioned is true in late-stage for Series B financing and above, but in fact today what we see is that in the seed rounds, preseed/seed there is in fact a little too much capital, and in fact today the VCs, the problem that there is and why we have difficulty finding GAFAMs is if we actually go back to the history of French venture capital, in fact they are spin-offs of banks and then over time they actually recruited the sons of their LPs [Limited Partners] or people who were in their network or people who thought like them who actually have a finance mindset. There are very few engineers, very few scientists who are actually in these VCs. […] To create GAFAMs, to create for example openAI, Sam Altman comes from the world of Computer Scientists, look at Elon Musk, he is a Computer Scientist, you look at Mark Zuckerberg, he is a Computer Scientist, and in fact to create the GAFAMs of tomorrow it will actually come from people who have a strong scientific culture or who have cultures that are different it can be people who perhaps did not graduate from engineering schools, people who are very different but the VCs are stuck in a mindset and the people in the ecosystem in general too. […] For example Mistral at the time when Arthur Mensch, Guillaume Guillaume Lample and Timothée Lacroix did their first fundraising, uniformly all the VCs all said ah yes what they do is great “yeah but hey they are researchers anyway”, they do not know how to break out of the mold of CEO who went to HEC.”

Mehdi, we supported you at the start-up studio, but before talking about business, we’ll come back to that later. I remember maybe you don’t want to talk about it too much, but you wrote a wonderful essay on what a functioning ecosystem is for entrepreneurship. I reread it two days ago, it was in 2017 I think. Do you have the same vision of the ecosystem’s weaknesses and what a country must do to promote people like you 8 years later?

“So yes, and even more unfortunately, even more so, and I’ll explain why. Yes, money is an issue, but even Sam Altman today, who is at the head of OpenAI, who has just made, who has just said that he has an annual turnover of 10 billion, has financing problems. But for me, the problem, the big problem in the ecosystem, is ambition, it’s the ambition of European entrepreneurs. In California, he would tell you, “I’m going to change the world,” they have an ambition that has no limits, and be careful, it’s not genetic, they are trained for that, they have accelerators like Ycombinator, they have advisors, they are often coached by other entrepreneurs who have had exits or who have made very large companies, and they are fueled by ambition, which I think we lack here. [What’s also missing] is investors who also work on feeling, who work on entrepreneurial ambition, who will go and fight for a billion or a hundred billion dollar case. Money is not the main problem for me because there is money, especially in seed funding in France with the BPI. After that, it is the ambition that must match, and the execution of course, the execution is not simple, but Arthur Mensch raised 100 million on slides in 3 months because he had an ambition at that time. “Unfortunately in Europe we are still in an ecosystem where we make technology with money where others make money with technology.” […] Sam Altman coached close to 1000 startups when he was at the head of Ycombinator, he saw an ecosystem, he saw innovators, he trained himself, that’s why today he says we will make a generative AI, an AI that will be a company that makes 1 billion, a person will be able to make a billion in value thanks to an AI and a only employee but because they are trained. Now look these are what Alain Damasio calls hyperstitions [https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/hyperstition] we are beyond superstition sometimes, we fall into lies, we fall into ideology so we in Europe we are a little more careful. [In the USA we say] “go for it, go for it, we support you, we will go with you” but today I do not know anyone in Europe who would act like that because they are trained in the USA. It is really an INSEP of entrepreneurs that we need.” […] Entrepreneurship is like playing poker you have cards in hand and then there are cards that arrive and as you go you have to adapt. We need people who will free us up, not just as entrepreneurs!, but who will free up the bandwidth to be able to understand what is happening. For me, these are advisors who have made the Champions League.”

Alexis Robert: “I am very aligned with Mehdi […] there are [so many people who] reject you because in fact you do not speak in the languages of the mold. In fact that is the problem today, is that in fact the entrepreneur feels alone and certain types of entrepreneurs who have a scientific and technical background do not know where to turn and today what is happening in San Francisco, what makes San Francisco great, is because in fact you get off the plane directly you have the feeling of being accepted as a geek, you have the feeling of being at the right place, you have “role models” who are there for you, who pull you up, you have the feeling that you too can be able to do this and in addition there is a sense of community which is extraordinary; you arrive, you are in the street, you speak with a VC, well, he listens to you or not, you have Sam Altman who passes in the street and you can say hello, you sit in a cafe and you talk, you have entrepreneurs to talk to, speaking is easy, introductions are easy and fluid, you can surround yourself with people who allow you to learn and improve because, as was said in the first panel, if you have understood general relativity, succeeding in pitching is not very complicated, you will succeed in doing it and in fact that’s what I wanted to say.”

I stop here and the people said much more. This is unfair not to share everything… But I think it gives you a feeling of what are challenges and opportunities are !

The Tour Triangle designed by Herzog and de Meuron, at the exit of Salon Vivatech, see also Instagram