This is one of the best books about innovation I have read in years. The importance of crazy ideas, not the recipe on how to make them successful, but the attitude to make them less crazy. And more importanly, crazy ideas have much more impact on our lives than we may think. A must read. Here are some extracts to convicne you…

Loonshot : a neglected project, widely dismissed, its champion written-off as unhinged.

The Loonshot thesis :

1. The most important breakthroughs come from loonshots, widely dismissed ideas whose champions are often written off as crazy.

2. Large groups of people are needed to translate those breakthroughs into technologies that win wars, products that save lives, or strategies that change industries.

3. Applying the science of phase transitions to the behavior of teams, companies, or any group with a mission provides practical rules for nurturing loonshots faster and better. [Page 2]

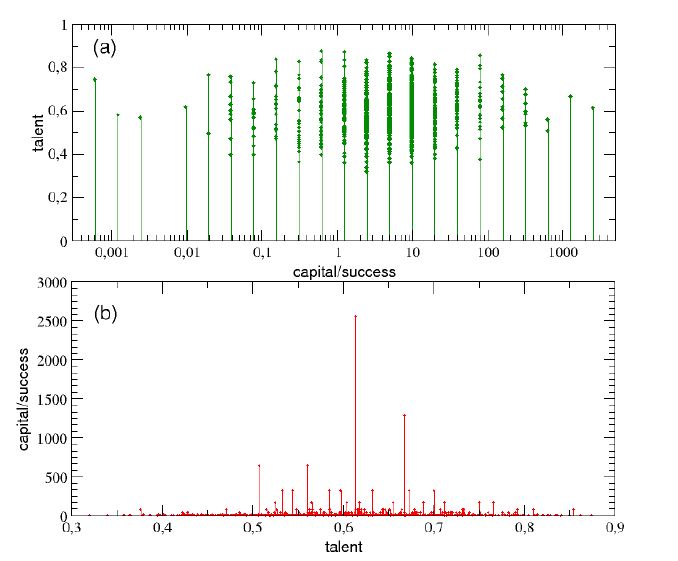

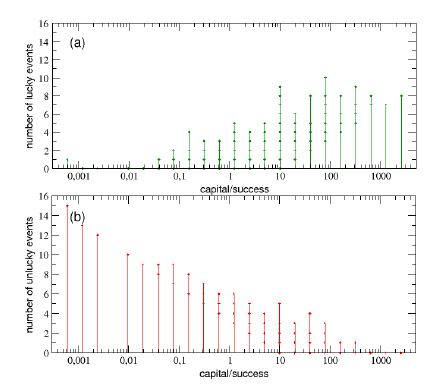

“Bush changed national research the same way Vail changed corporate research. Both recognized that the big ideas – the breakthroughs that change the course of science, business, and history – fail many times before they succeed. Sometimes they survive through sheer chance. In other words, the breakthroughs that change our world are born from the marriage of genius and serendipity.” [Page 37]

“But the ones who truly succeed – the engineers of serendipity – play a more humble role. Rather than champion any individual loonshot, they create an outstanding structure for nurturing many loonshots. Rather than visionary innovators, they are careful gardeners. They ensure that both loonshots and franchises are tended well, that neither dominates the other, and that each side nurtures and supports the other.” [page 38]

“As we will see over the next chapters, managing the touch and the balance is an art. Overmanaging the transfer causes one kind of trap. Undemanaging that transfer causes another.” [Page 42]

A project champion: On the creative side, inventors (artists) often believe that their work should speak for itself. Most find any kind of promotion distasteful. On the business side, line managers (soldiers) don’t see the need for someone who doesn’t make or sell stuff – for someone whose job is simply to promote an idea internally. But great project champions are much more than promoters. They are bilingual specialists, fluent in both artist-speak and soldier-speak, who can bring the two sides together. [Page 63]

Contrarian answers, with confidence, create very attractive investments. [Page 63]

LSC: Listen to the Suck with Curiosity. LSC, for me, is a signal. When someone challenges the project you’ve invested years in, do you defend with anger or investigate with genuine curiosity? [Page 64]

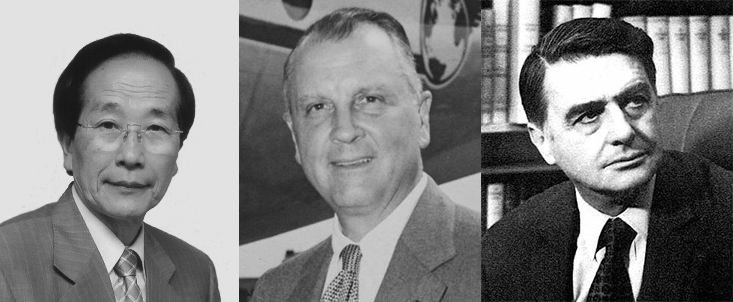

Some famous creators of Loonshots:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Akira_Endo_(biochemist)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juan_Trippe

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edwin_H._Land

Years later, Land became known for a saying: “Do not undertake a program unless the goal is manifestly important and its achievement nearly impossible.” [Page 96]

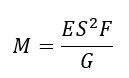

“Then the author has an amazing thesis about team size. “I will show that team size plays the same role in organizations that temperature does for liquids and solids. As team size crosses a “magic number”, the balance of incentives shifts from encouraging a focus on loonshots to a focus on careers.” [Page 164]

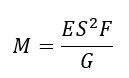

This magic number is

“Where G is the salary growth rate with promotion (for example 12%); S is management span – if it is narrow, each manager has a small number of direct reports and there are many hierarchical layers, whereas if it is wide, there will be more direct reports and less hierarchy – E is the equity fraction which ties your pay to the quality of your work. The final parameter F for fitness is return on politics vs. project-skill fit.

In many cases the magic number M equals 150… [pages 195-200]

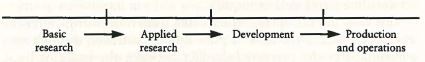

Safi Bahcall has many other rich descriptions including the importance of power laws in innovations [Page 178] or this one [Page 240]

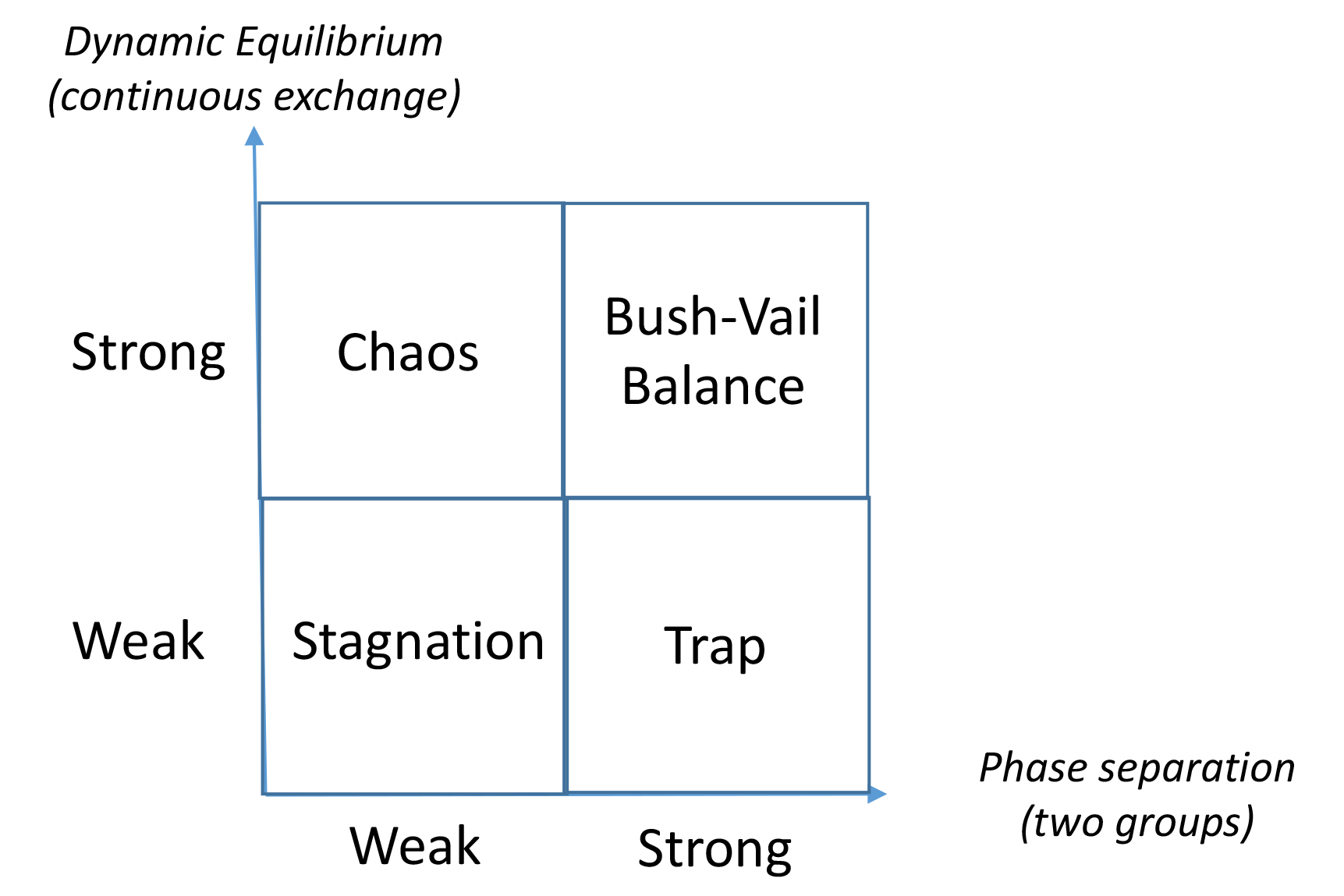

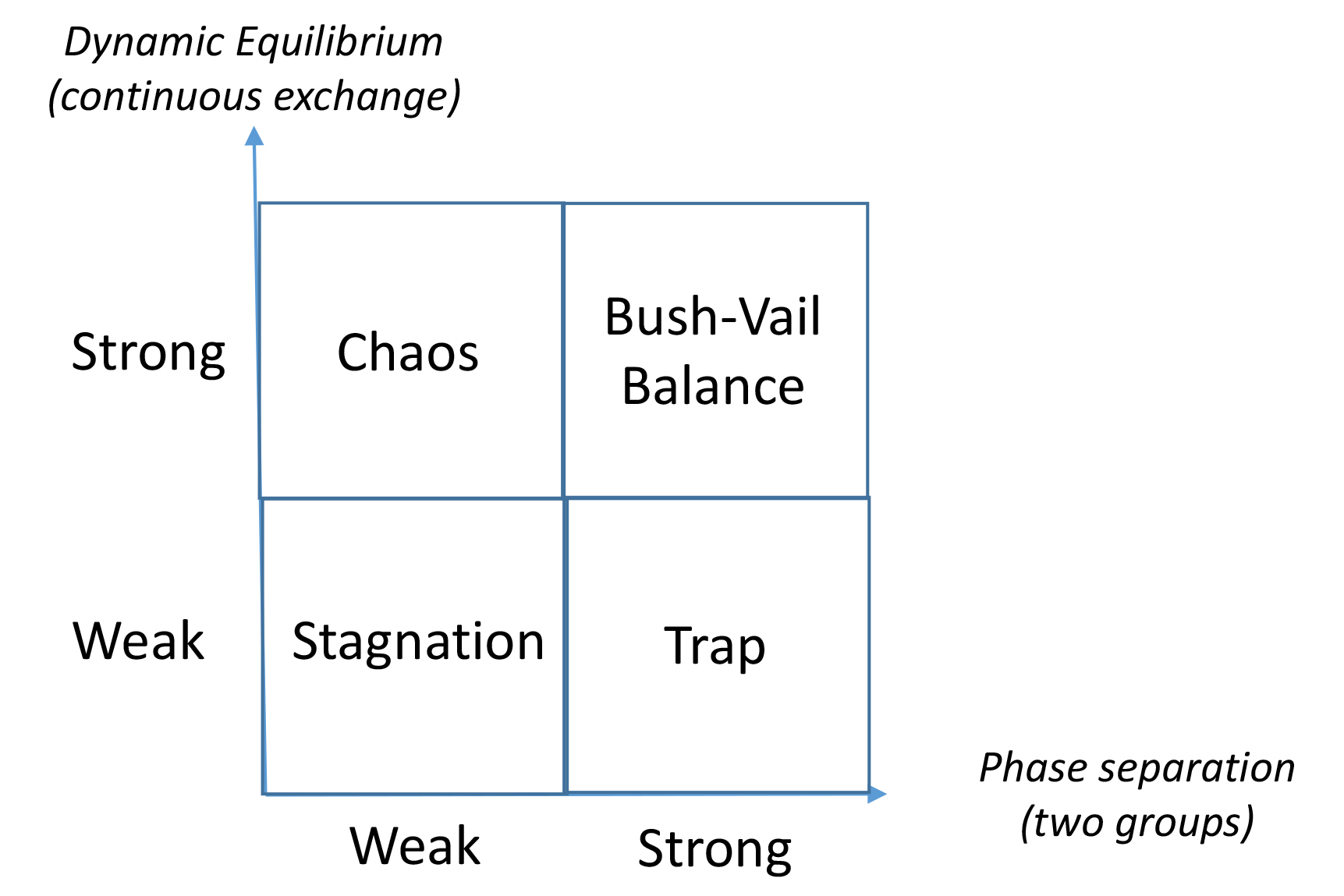

For a loonshot nursery to flourish – inside either a company or an industry – three conditions must be met:

1. Phase separation : separate lonnshot and franchise groups

2. Dynamic elequilibrium: seamless exchange between the two groups

3. Critical mass: a lonnshot group large enough to ignite.

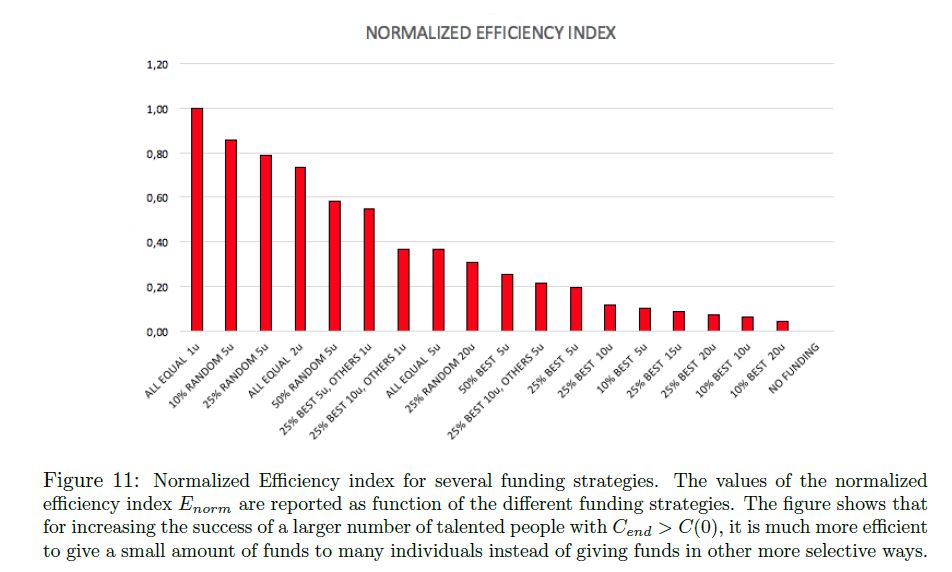

Applied to companies, the first two are the first Bush-Vail rules discussed in part one. The third, critical mass, has to do with commitment. If there is no money to pay for hiring good people or funding early-stage ideas and projects, a loonshot group will wither, no matter how well designed. To thrive, a loonshot group needs a chain reaction. A research lab that produces a successful drug, a hit product, or award-winning designs will attract top talent. Inventors and creatives will want to bring new ideas and ride the wave of a winning team. The success will justify more funding. More projects and more funding increase the odds of more hits – the positive feedback lopp of a chain reaction.

How many projects are needed to achieve critical mass? Suppose odds are 1 in 10 that any one loonshot will succeed. Critical mass to ignite the reaction with high confidence requires investing in at least two dozen such loonshots (a diversified portfolio of ten of those loonhsots has a 65 percent likelihood of producing at least one win; two dozen, a 92 percent likelihood).” [Pages 240-1]

Disruptive innovation again [Page 263]

Use “disruptive Innovation” to analyze history; nurture loonshots to test beliefs.

In an article addressing recent controversy about the notion of disruptive innovation, Christensen explains why Uber is not disruptive, by his definition, and why the iPhone also began as a sustainable innovation. In Chapter 3, we saw that American Airlines – a large incumbent, not a new entrant – led the airline industry after deregulation with many brilliant “sustaining” innovations targeted to high-end customers. Hundreds of low-cost, specialty airline startups, “disruptive innovators” failed.

If the transistor, google, the iPhone, Uber, Walmart, IKEA, and American Airlines’ Big Data and other industry-transforming ideas were all initially sustaining innovations, and hundreds of “disruptive innovators” fail, perhaps the distinction between sustaining vs. disruptive, while interesting academically or in hindsight, is less critical for steering businesses in real time than other notions.

That, at least, is why I don’t use the distinction in this book. I use the distinction between S-type and P-type because teams and companies or any large organization develop deeply held beliefs, sometimes consciously, often not, about both strategies and products – and loonshots are contrarian bets that challenge those beliefs. Perhaps everything that you are sure is true about your products or your business model is right, and the people telling you about some crazy idea that challenges your beliefs are wrong. But what if they aren’t? Wouldn’t you rather discover that in your own lab or pilot study, rather than read about it in a press release from one of your competitors? How much risk are you willing to take by dismissing their idea?

We want to design our teams, companies, and nations to nurture loonshots – in a way that maintains the delicate balance with our franchises – so that we avoid ending up like the Qianlong emperor. The one how dismissed those “strange or ingenious objects”, the same strange and ingenious objects that returned in the hands of his adversaries, years later, and doomed his empire.