I am again taking advantage of the questions asked to me to write a post (after the one on the impact of the personality of founders on the success of startups). I could have titled this post “what do investors expect?”, I look here at both subjects.This time, I even copy a part of the message I received:

Context: Just to share with you the dynamics of investors (very early stage) who look at my project. I have received 10+ requests, sometimes from investors who want to make an initial contact call (to follow developments in typically 6 months). Some display their investment thesis upfront (sometimes stratospheric expectations). I try not to waste too much time with such requests, to focus on my product (and Product-Market-Fit – PMF, *the priority*!), but what do you think of this typology of investors? Very early, who favor the blank page vs. PMF but with enormous expectations (100x potential ROI).

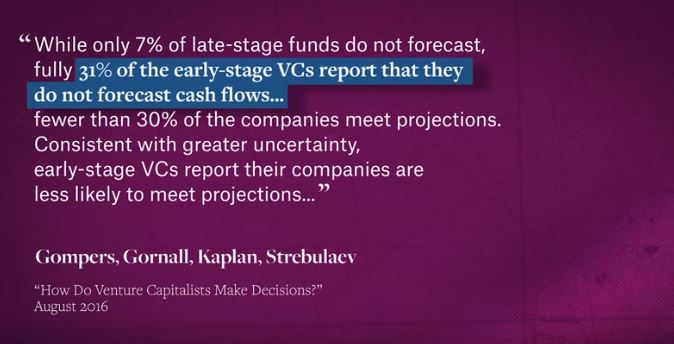

(I know that several entrepreneurs are experiencing a bit of the same thing at the moment). I can’t imagine how a founder can calmly seek his or her PMF having onboarded this type of VC and under their pressure (100x and not 10 or 20x!)…

Questions :

1) Are they intrinsically better or worse than more “common” funders (5x-7x under ~5 years, or 10x under 7-10 years)? (I’m exaggerating on purpose, of course).

2) The less-pressing alternative would be a collection exclusively made up of BAs and/or BA-Networks, but does the absence of institutional SEED investors send a bad signal to VCs? A sign of too little ambition? A potential lack of initial attractiveness?

3) There is a strong trend towards “leaner startups” which give less and less equity in pre-seed / seed (including to YC). However, institutional investors often want a double-digit equity share. What is your vision/experience in European VCs? Is leaner (equity shared) better or less attractive? Many startups (even at YC) do not give more than 10% of total equity across the SEED round (+ the initial 7% from YC, or other more or less equivalent SAFEs).

I answered a little quickly like this and I’m going to add a little more, notably a new update: an update of my pdf of cap tables, which includes more than 900 companies now…

This is a true wrong question! But I’m not an entrepreneur, I’m a mentor!

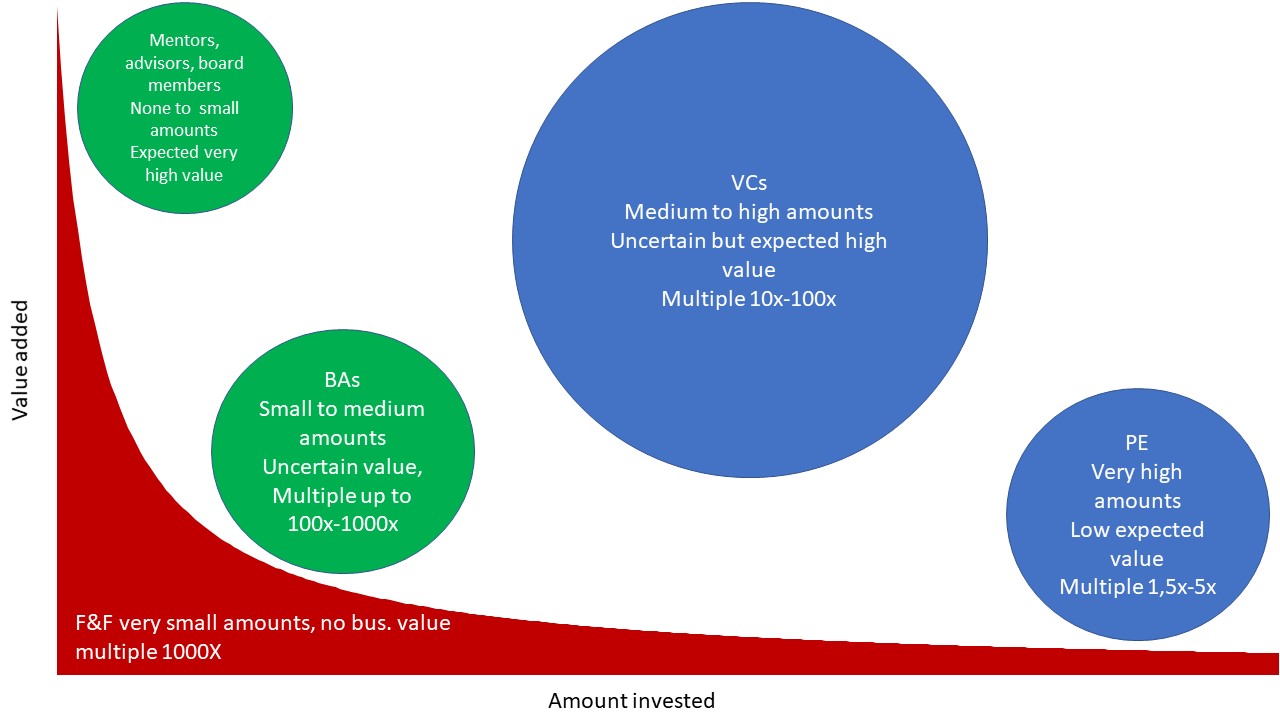

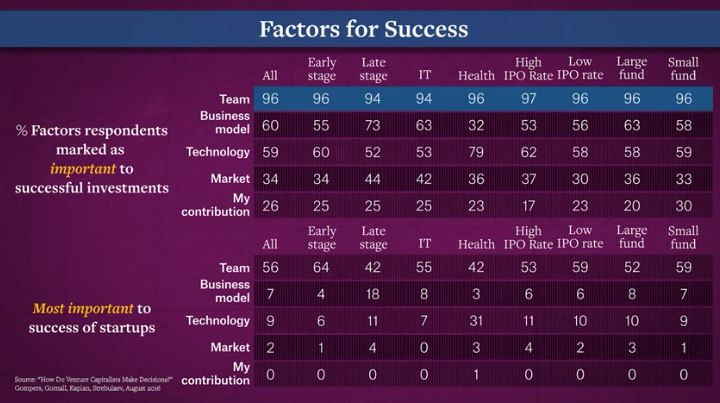

The main thing is the added value of your investor in two dimensions:

– the amount invested,

– the quality of advice.

We could almost say that if one of the two dimensions is zero then the other must be very high, and we can therefore accept that one is weak.

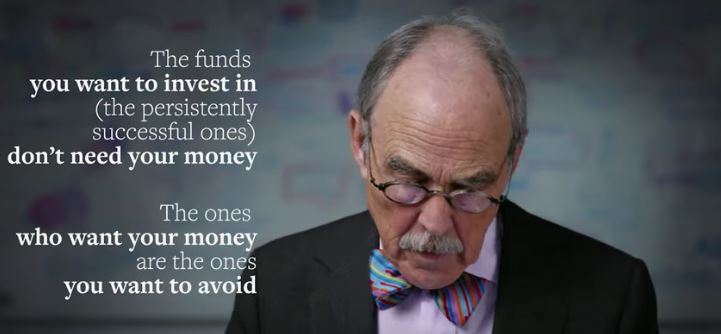

You dream of having a renowned VC or BA (her name and her credibility), this undoubtedly has a price!

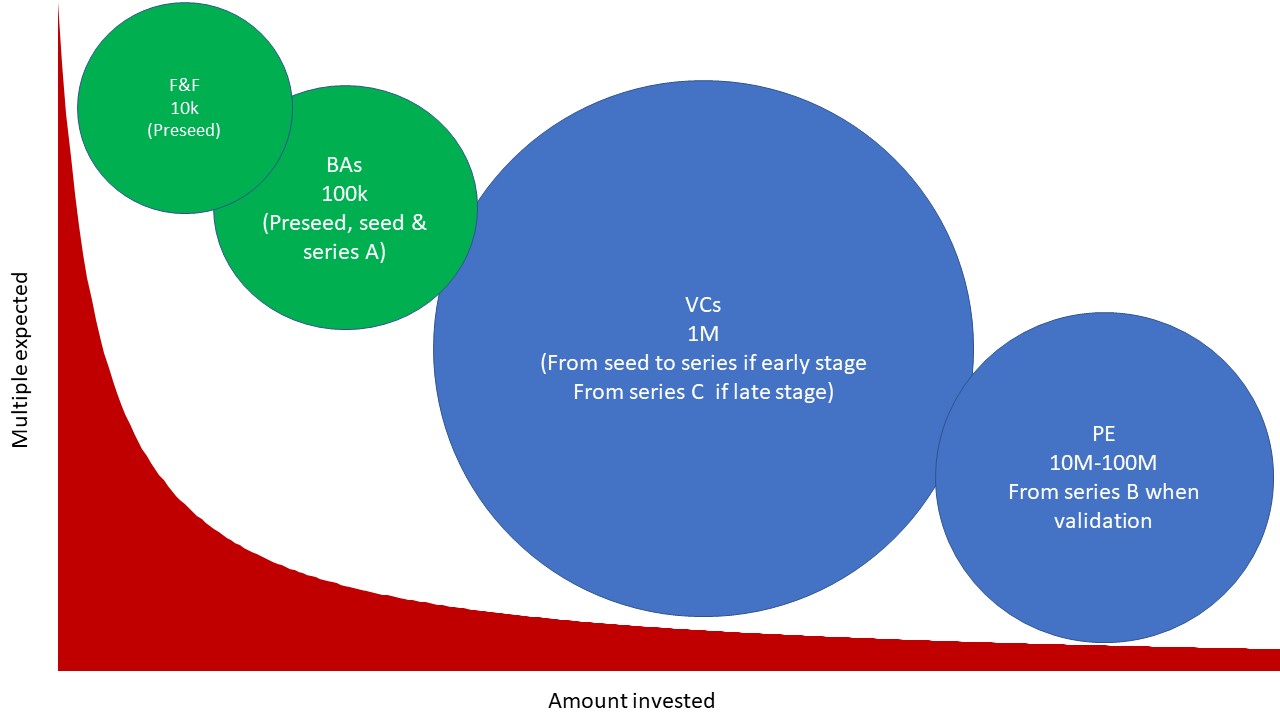

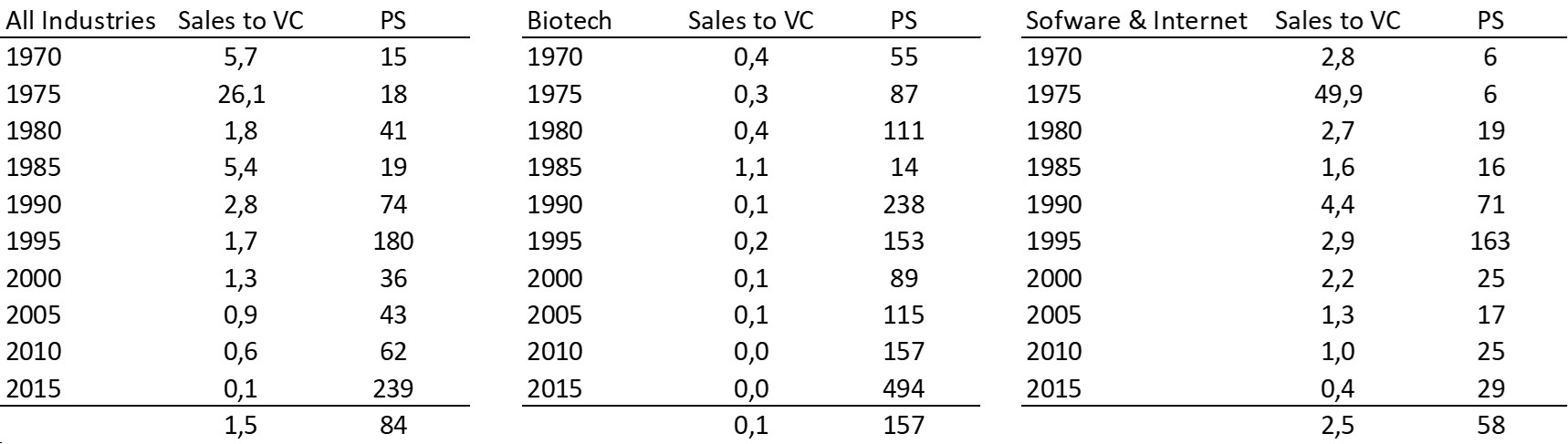

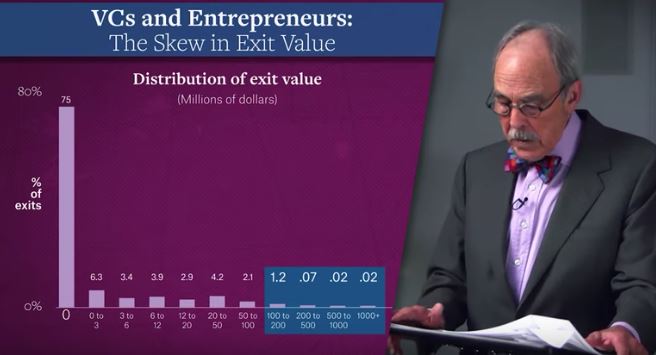

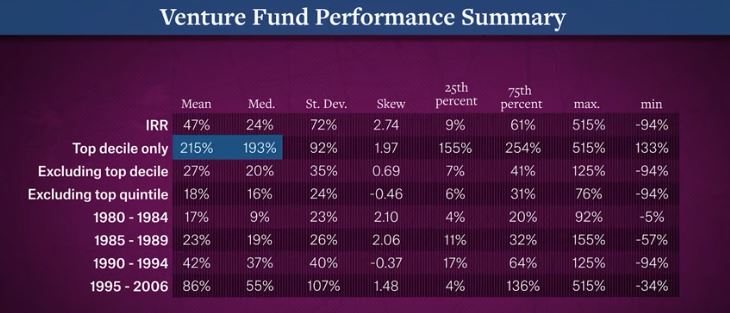

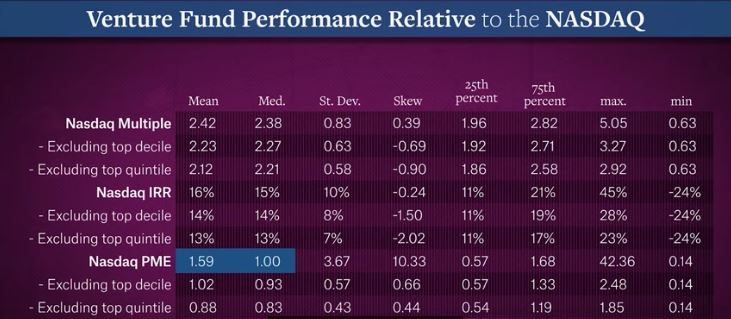

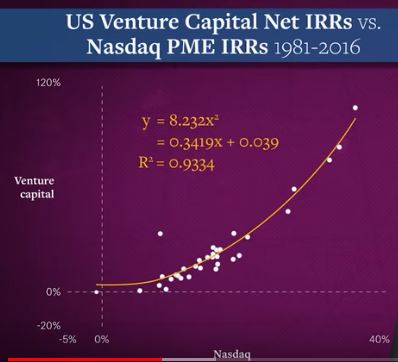

Then the lower the amount, the greater the expected multiple. If you put 10k you hope to make x1000, if you put 100K you hope to make x100 if you put 1M you hope to make x10.

In reality it’s more a question of stage, in series D, E, F, it’s probably 2x-3x, in A, B it’s 10x, in seed, it’s 100x, in pre-seed it’s 1000x

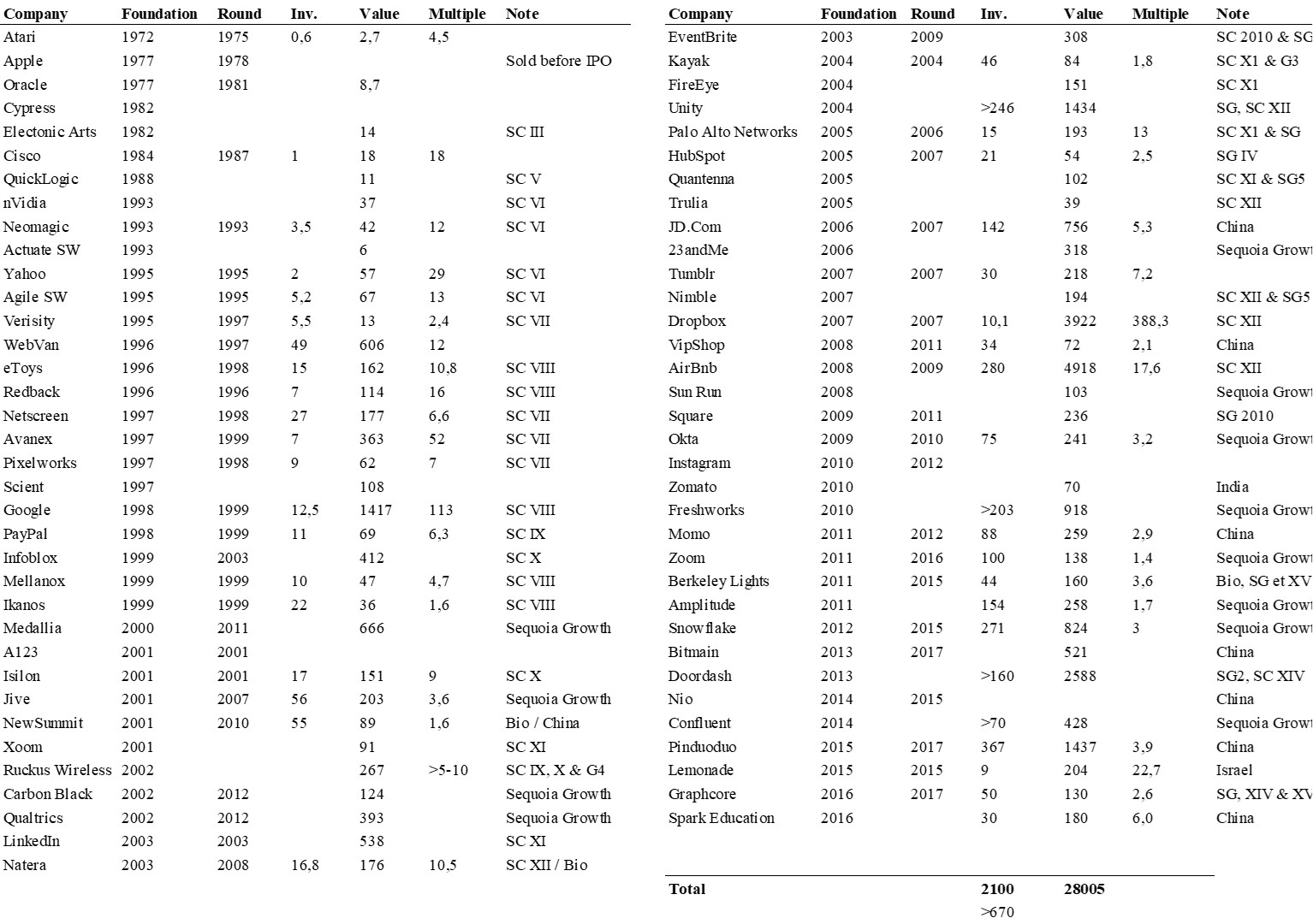

– Google had David Cheriton and Andy Bechtolsheim as BAs, they put in 100k, I think they made 400M…

– Sequoia and KP put in $12M and made $2B

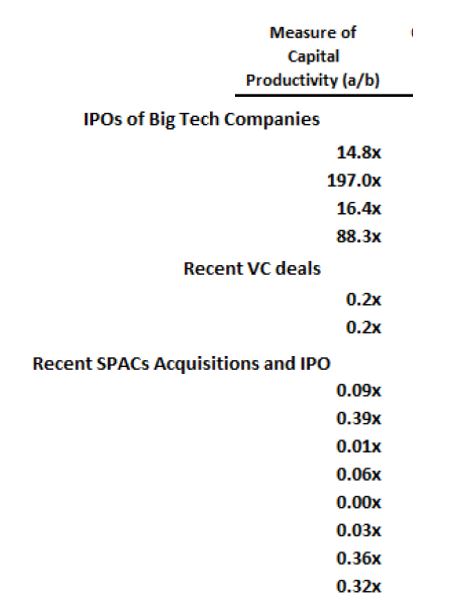

(see page 47 of the pdf, $85/$0.06 and $85/$0.52 for the multiples at the IPO but they sold at least six months later and I think it was worth at least 3x or 4x more)

On the last point, it’s not easy either, but Stanford had around 2% of Google at the time of creation, which is unusually low and it is paradoxically their biggest grain, we can see the diversity of criteria.

So let me add a couple of points. I thought Paul Graham (YCombinator) would have provided answers on his blog paulgraham.com but did not find an answer. Howver he keeps on writing great things like:

– How to start Google (March 2024) https://paulgraham.com/google.html

– Superlinear returns (October 2023) https://paulgraham.com/superlinear.html

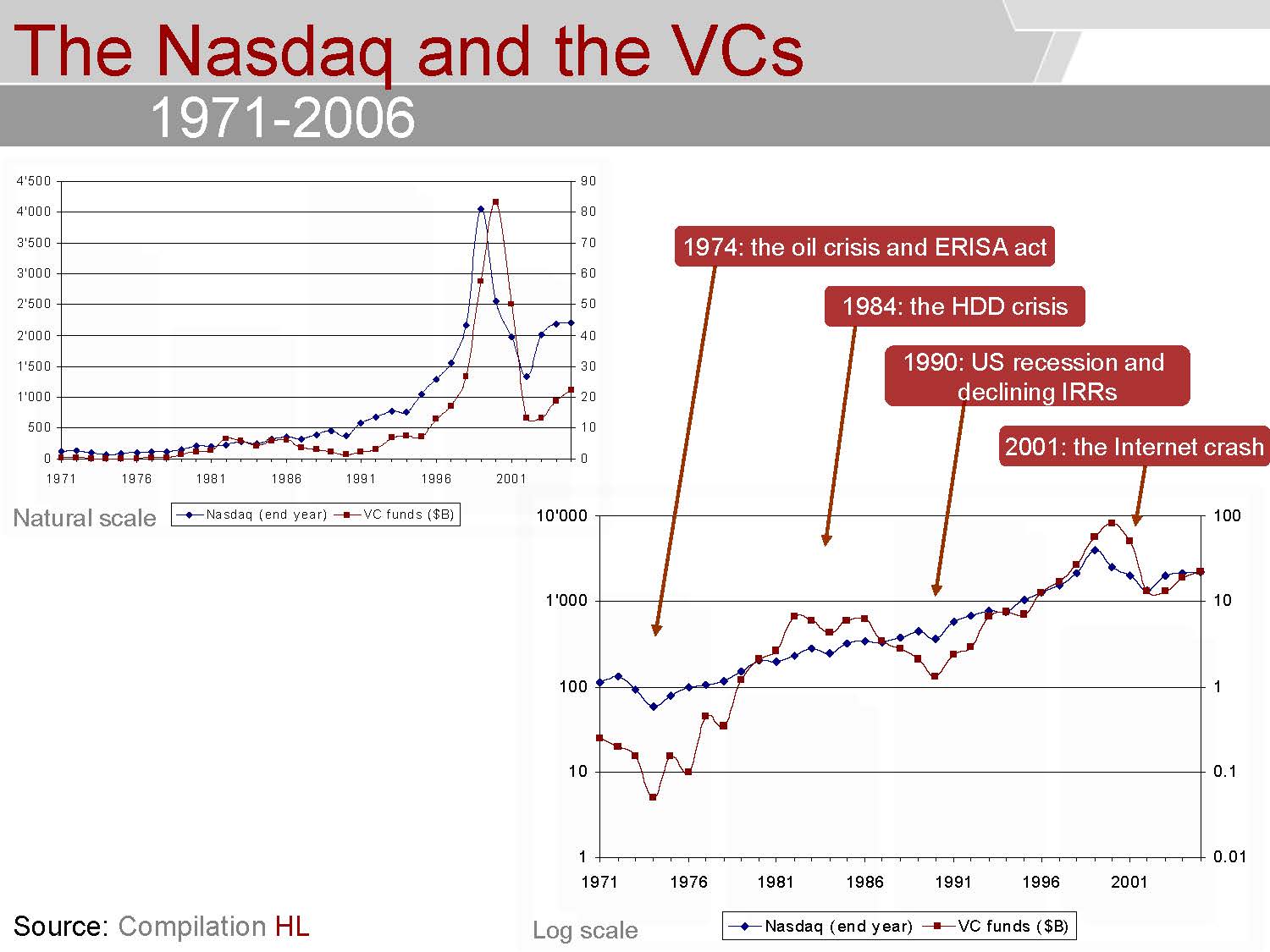

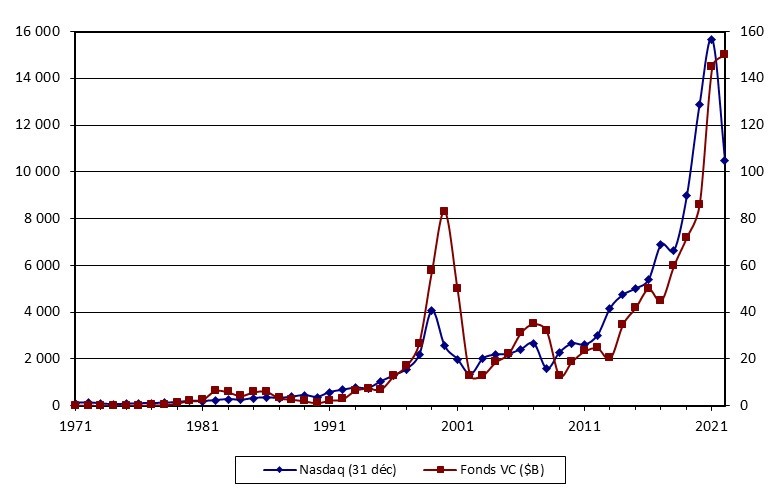

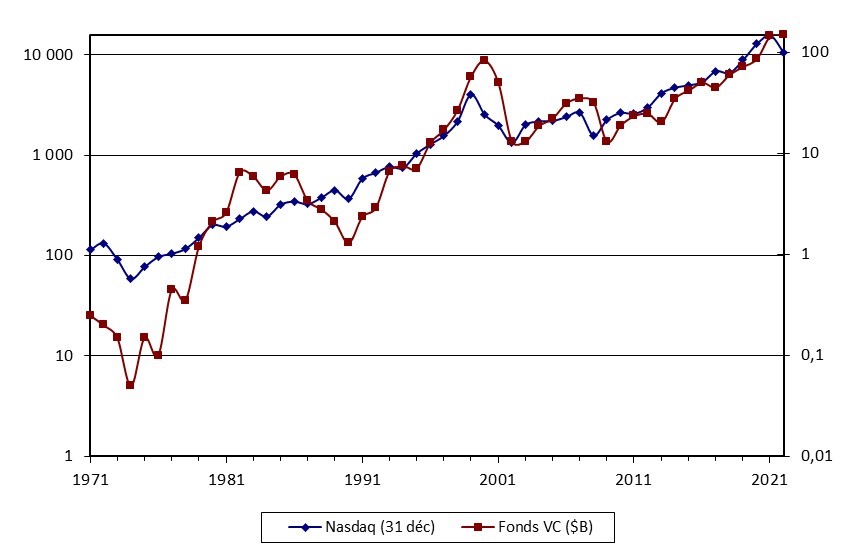

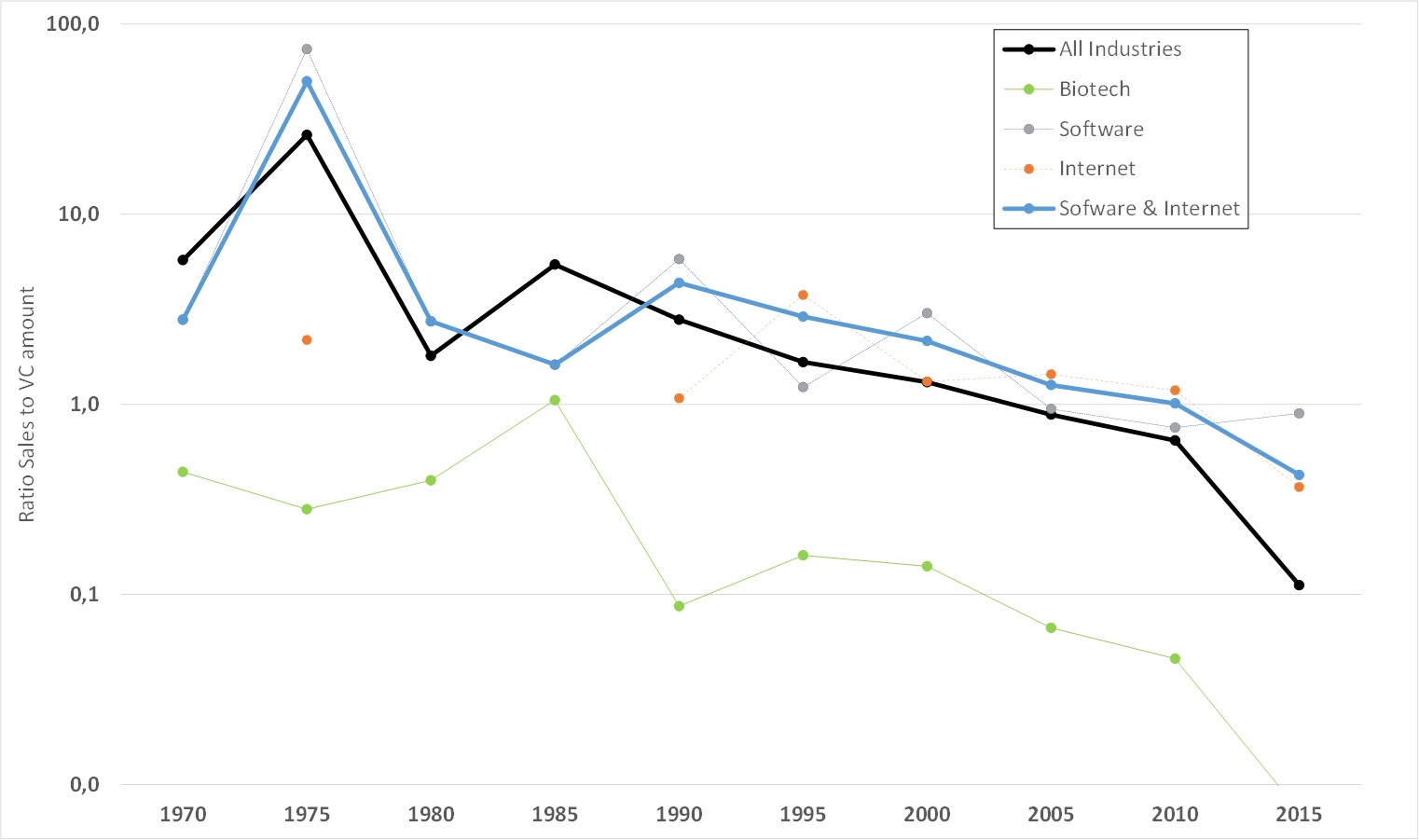

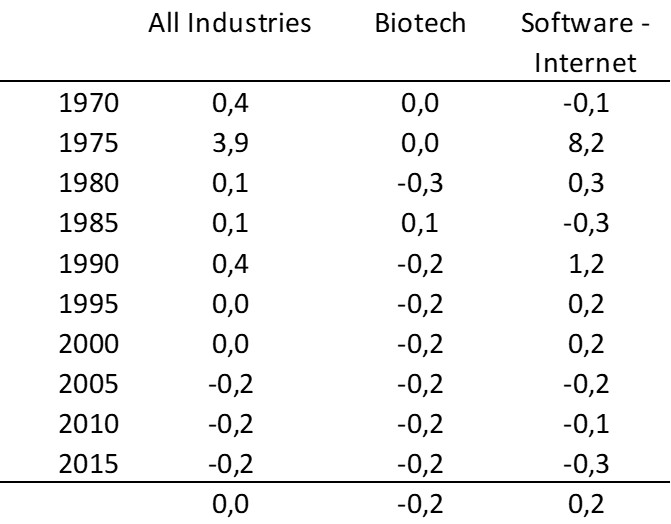

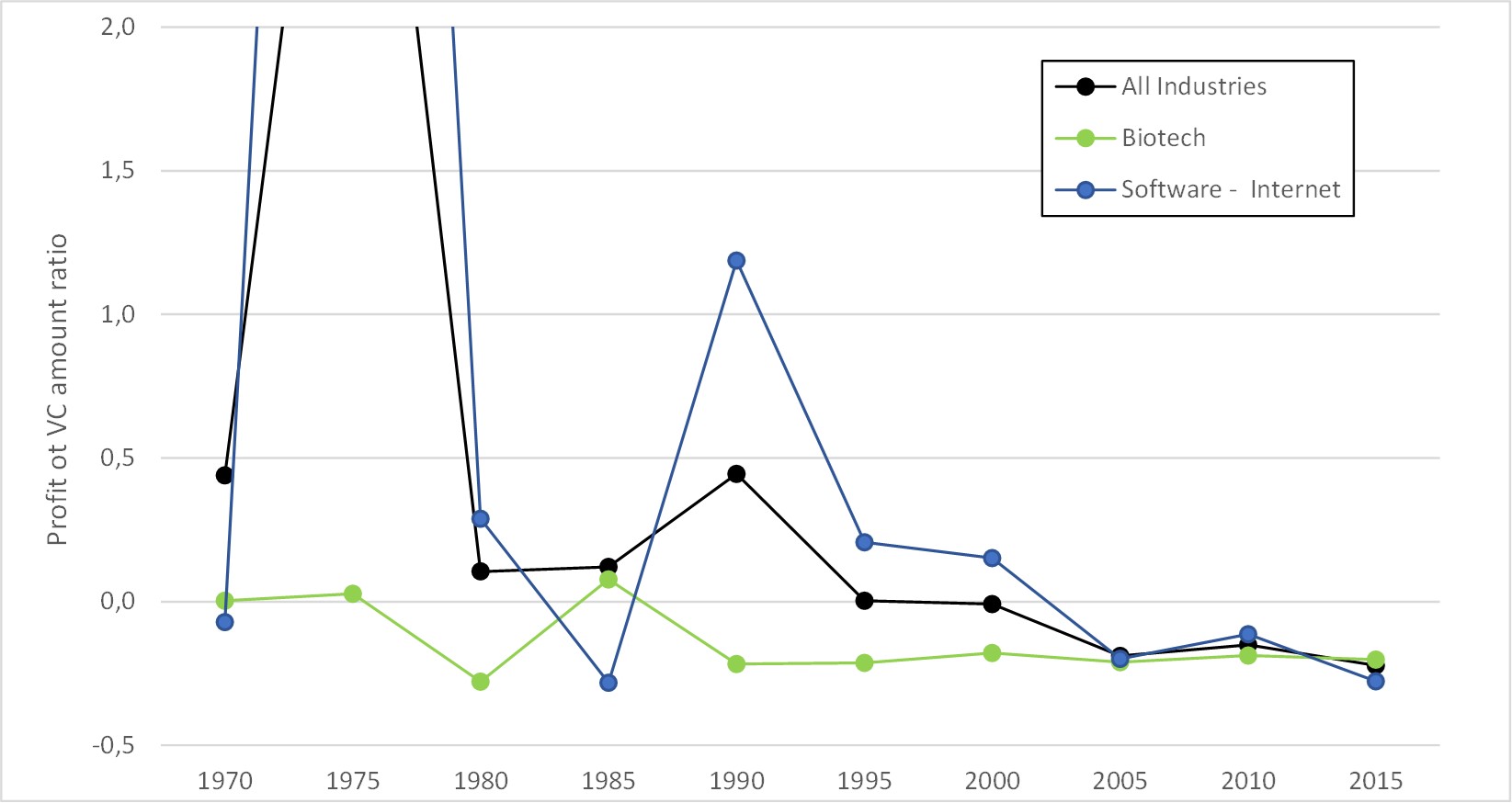

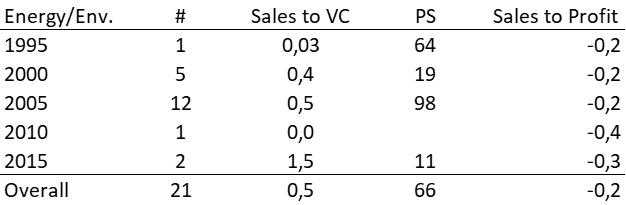

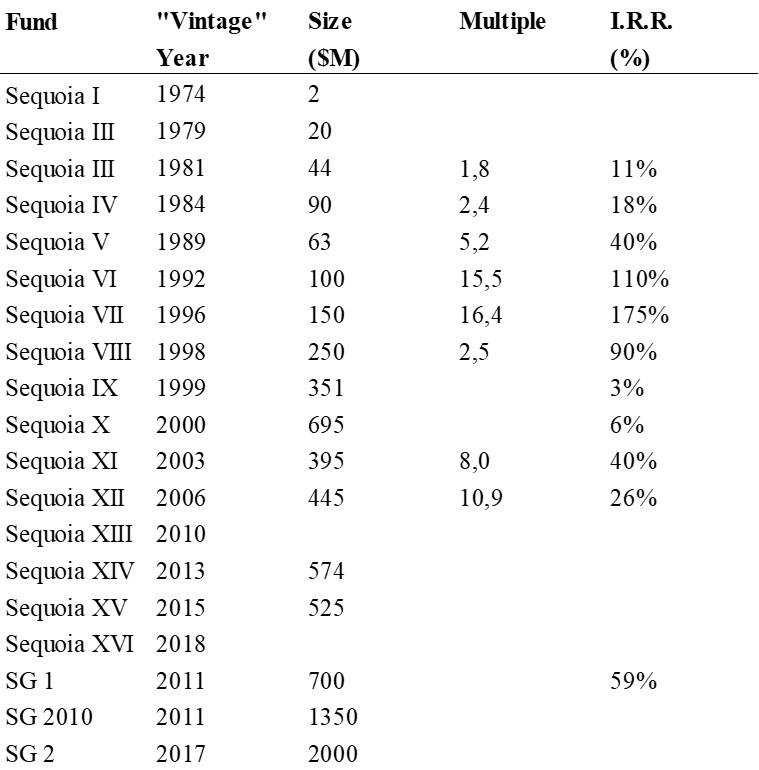

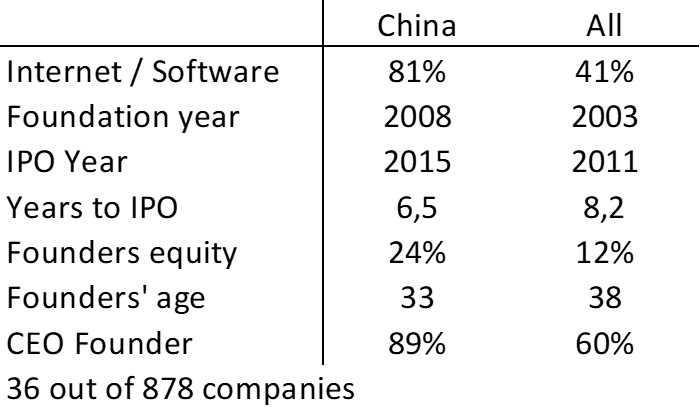

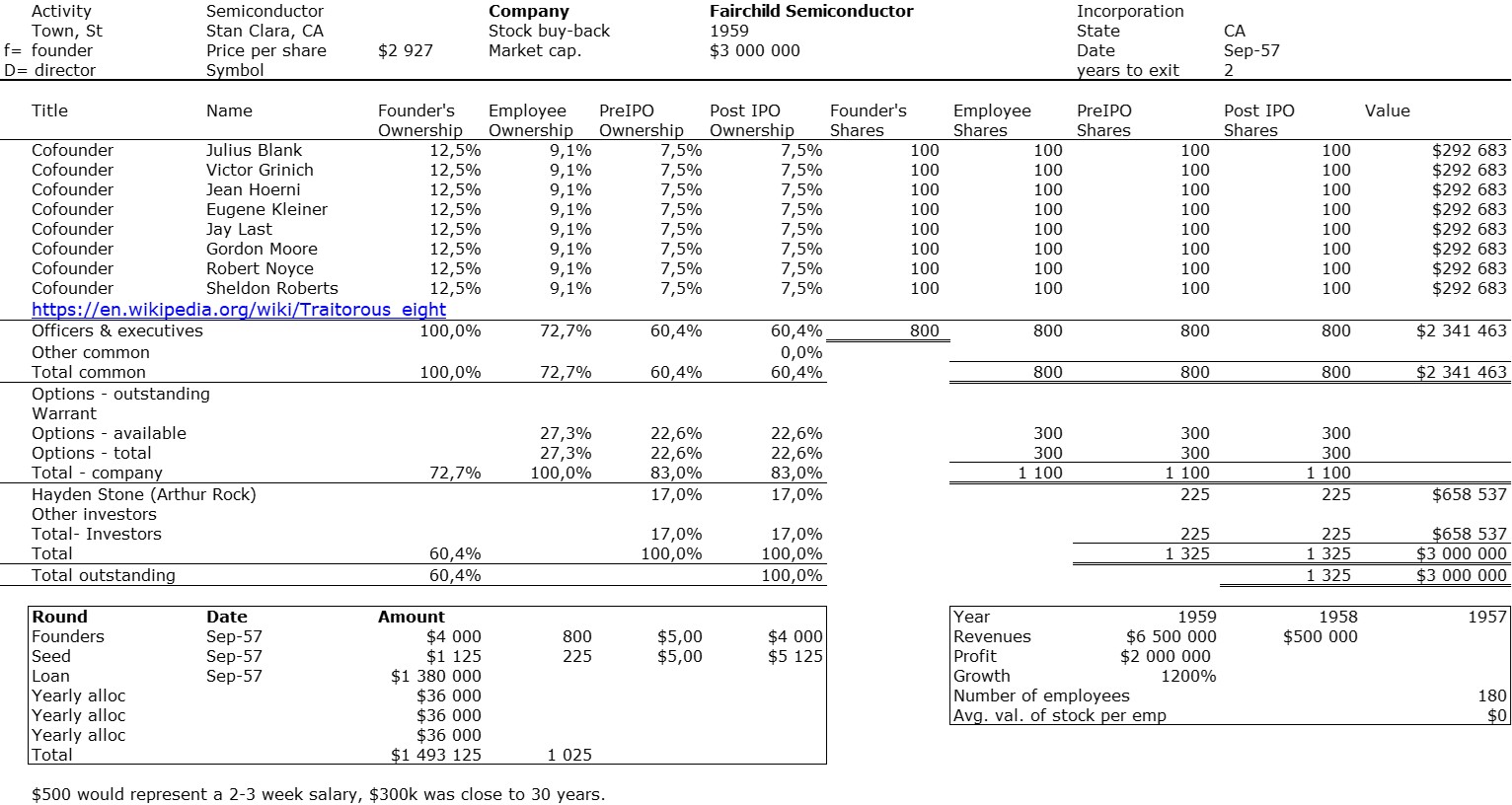

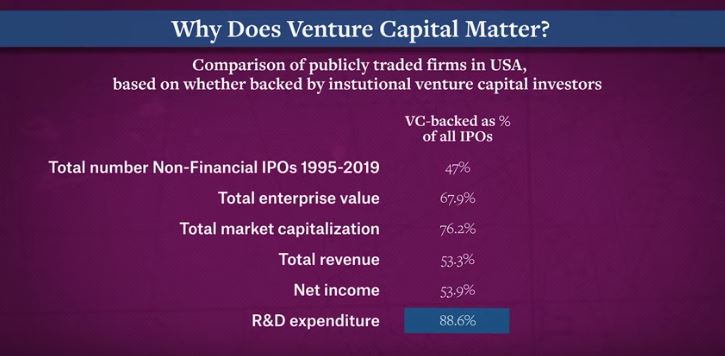

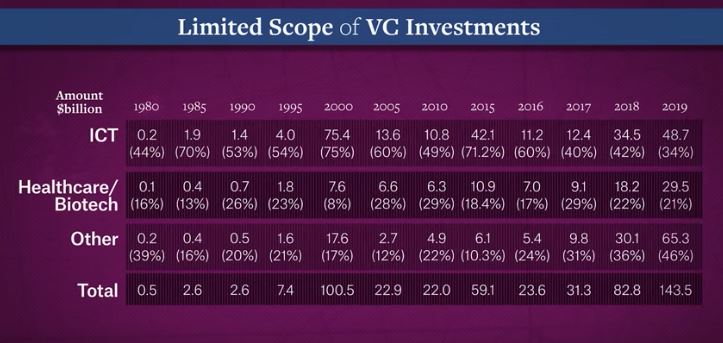

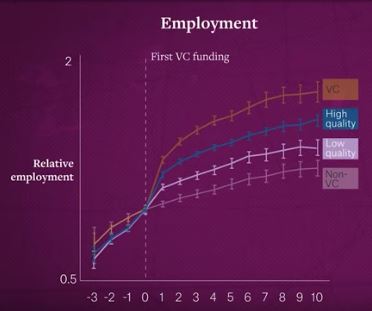

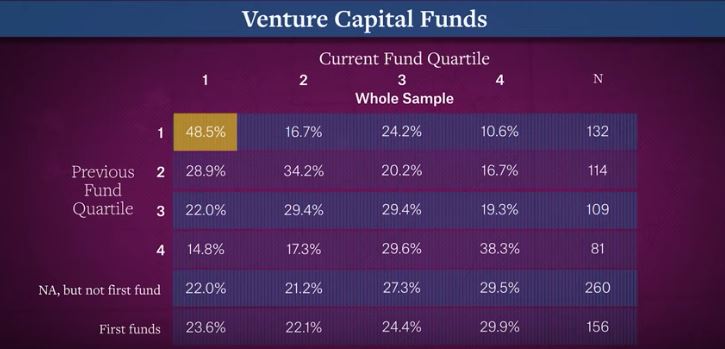

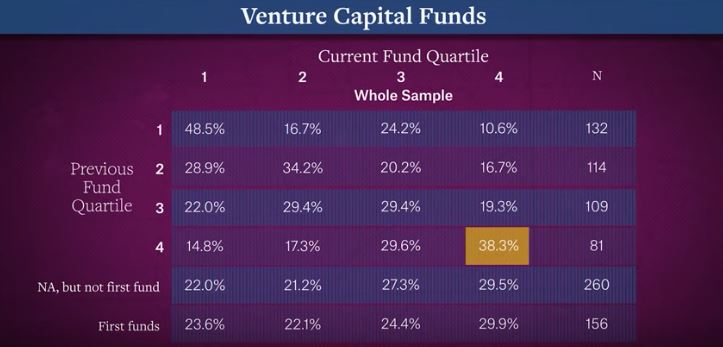

The two figures that follow illustrate the explanations above. The pdf therefore gives more than 900 cap tables which can illustrate the diversity of multiples (theoretical at the IPO).

Finally, it is still quite rare for an investor to contact an entrepreneur directly (even if it can also happen). The contact is rather established by a third party who knows both the entrepreneur and the institutional investor, for example the Business Angel or the mentor…

Finally, the percentage given in return for an investment is not linear either. It depends on the stage of development of the company of course but on the amount itself!

– for 100k, we typically give 5-15%,

– for 1M it’s more like 40%,

– for 10M and more we fall back to amounts of around 10%.

This may seem counterintuitive and it shows that the percentages are not the result of accounting but of negotiations.

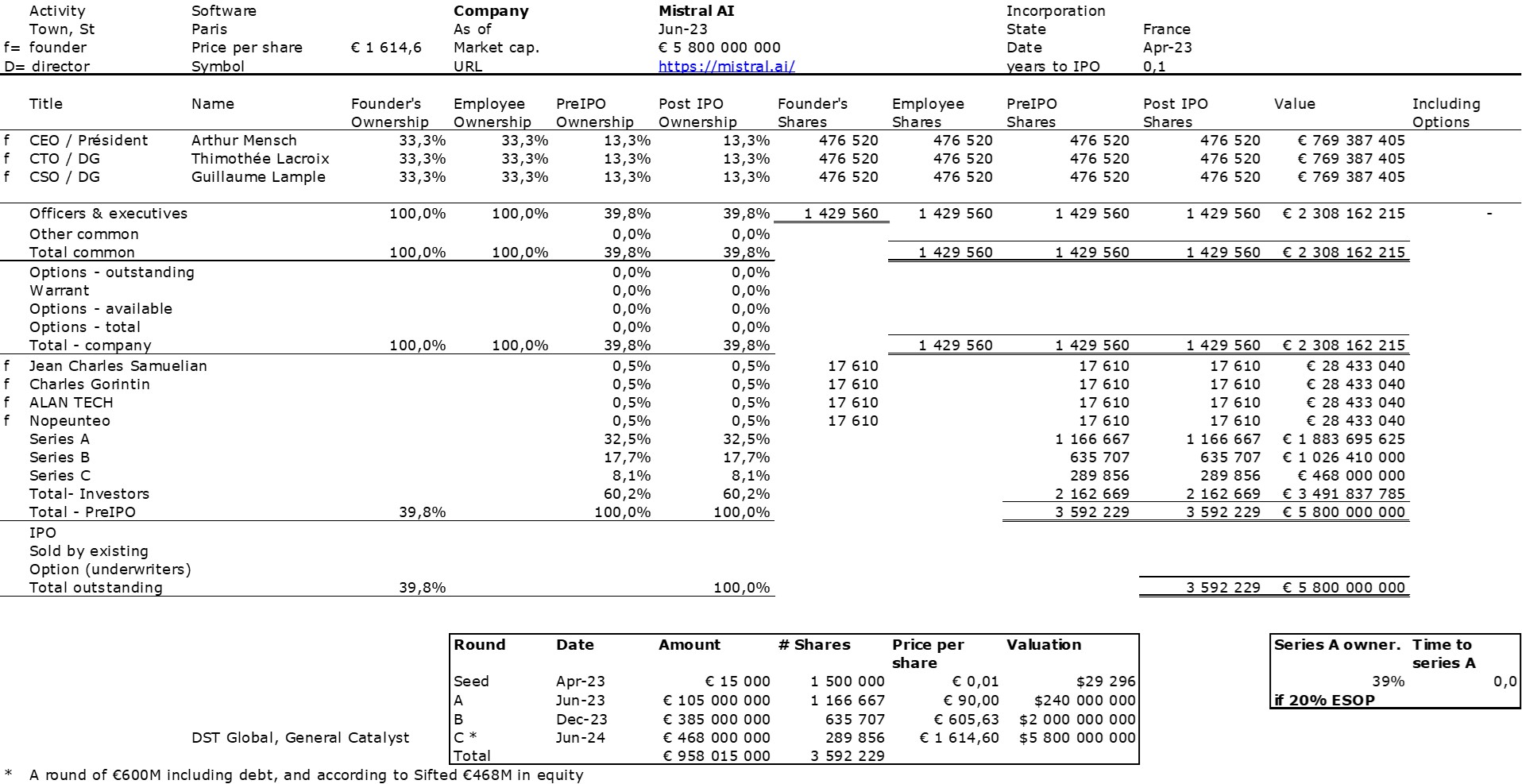

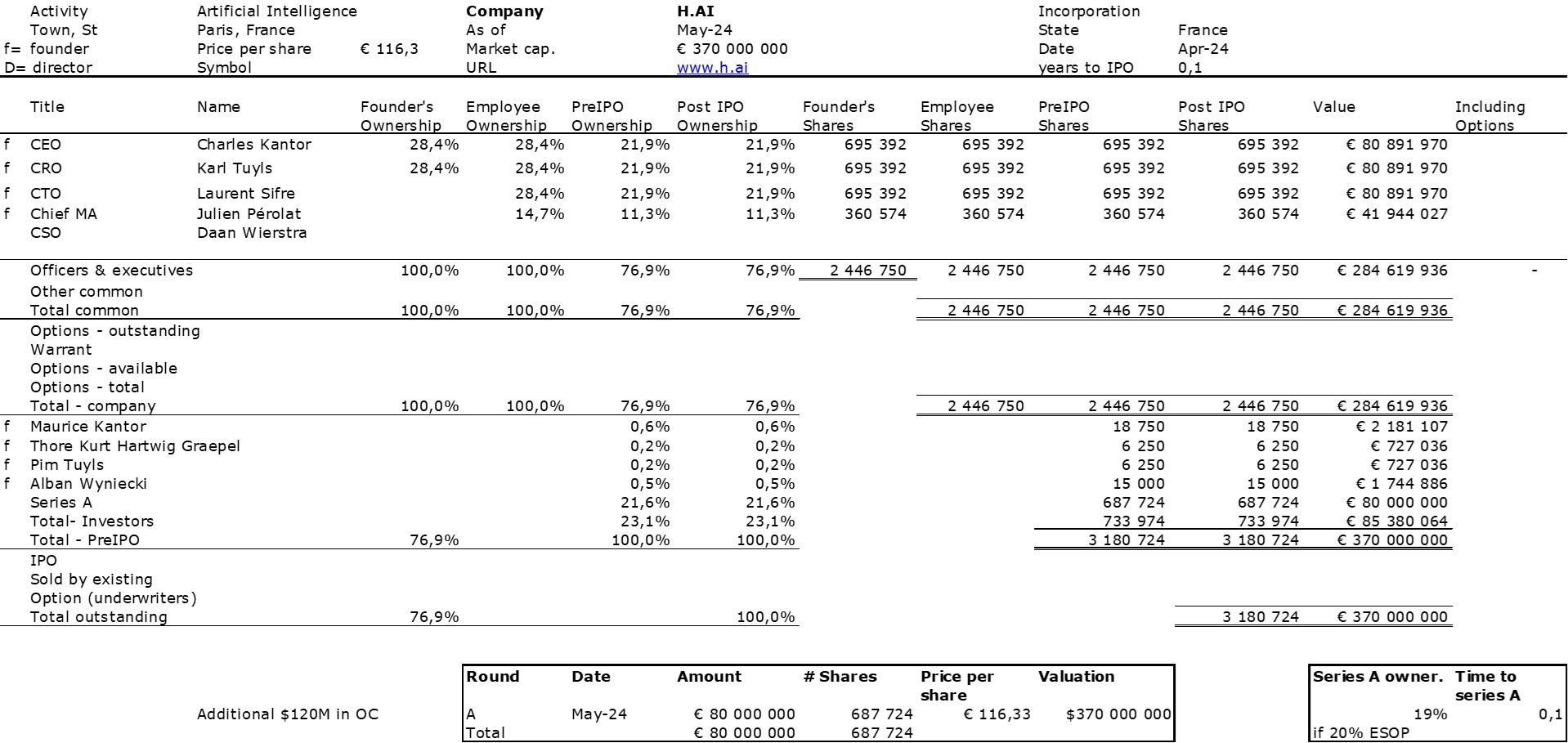

I add two recent French startup cap tables, Mistral AI and H.ai which show that exceptional fundraising leads to exceptional valuations and therefore unusual percentages. These were built with assumptions given my media or data from company documents.

The BA, business angel, is a wealthy individual who invests his own money (generally at least 100k per startup). Below we are talking more about F&F – Friends & Family.

VC (venture capital) invests third party money (pension funds, companies, banks, insurance companies, very wealthy individuals) generally with a minimum of 1 million per startup.

PE, private equity, is an institutional investment firm which takes less risk (even if the companies are not listed but generally profitable or with stable turnover). They invest large amounts but do not expect returns on investment as high as the VC.