Here is a short, dense and convincing essay that anyone interested in innovation should read. The subject is nevertheless complex, but the author gives a clear and argued vision of it. So here is my summary or rather selected extracts, because you have to go directly to the text which only takes an hour or two to read!

A diagnosis

Taxation?

In the top 1% of the income distribution, around 70% of taxpayers receive income from entrepreneurship, a figure which increases further for the richest, reaching 85% for the top 0.1%. [Page 21]

A list of individuals with the highest wealth is drawn up each year by Forbes magazine: less than 10% of the individuals appearing on the list in 1983 are still there in 2023. [Page 23]

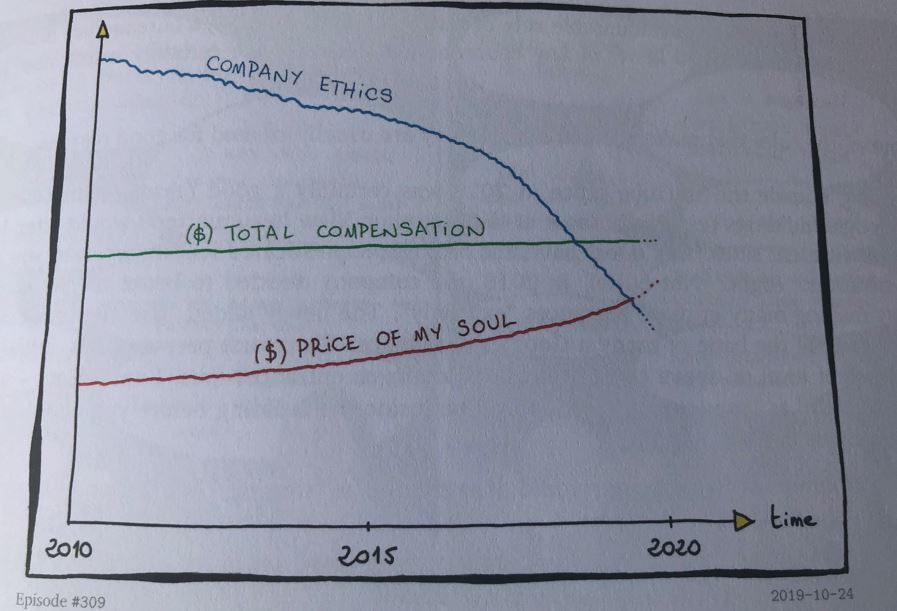

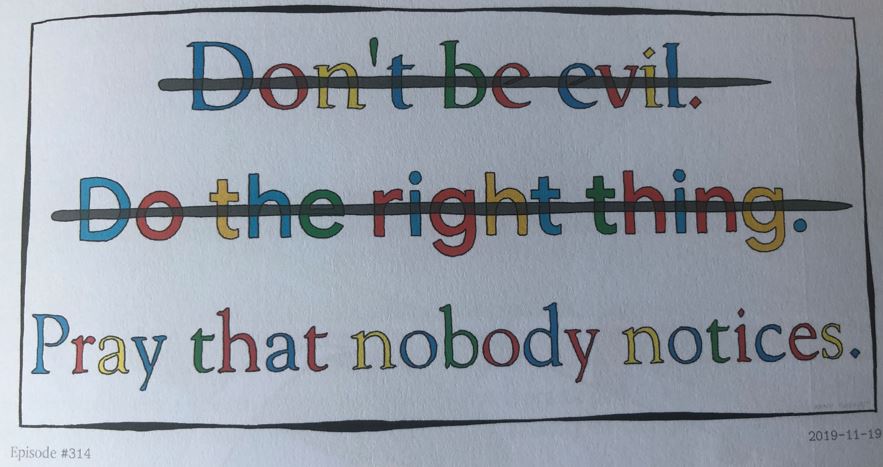

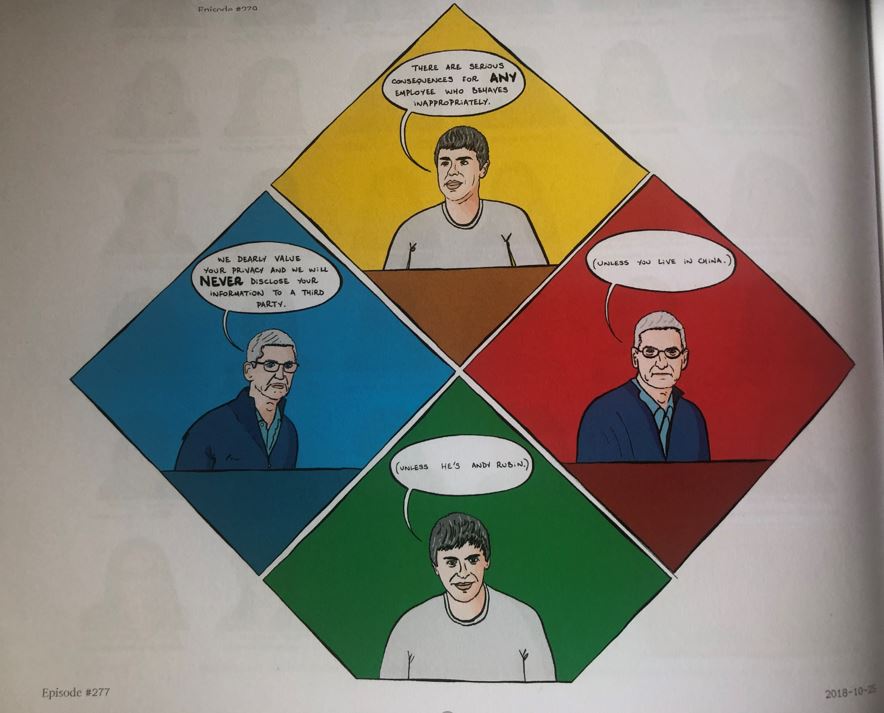

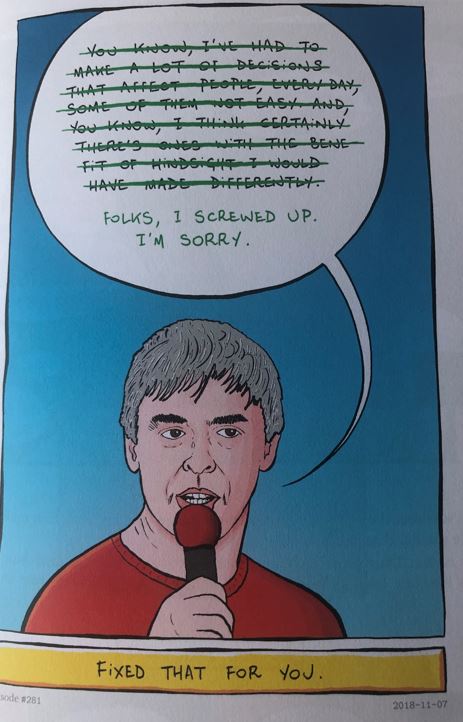

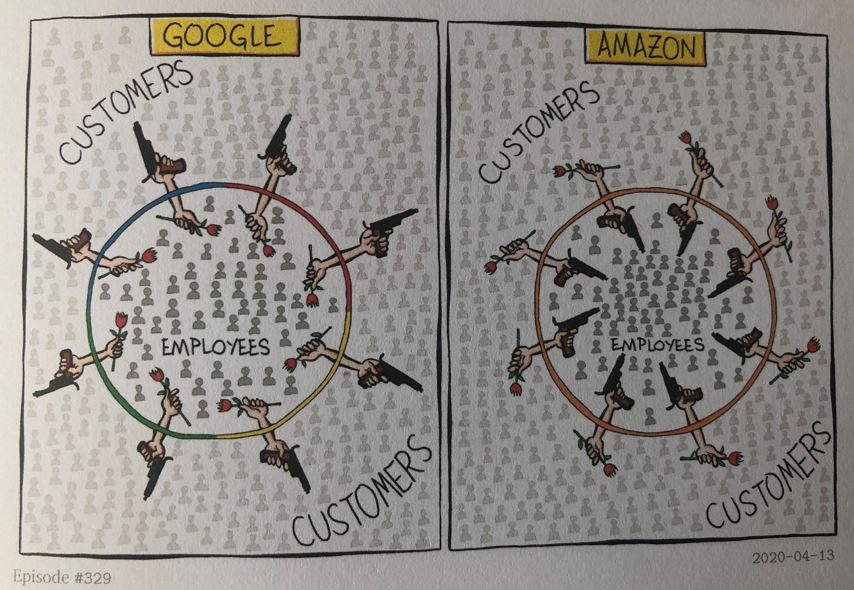

The author is not convinced that taxing the rich is a solution to the inequalities created. Provided that the incentives and dynamics do not ultimately favor a tiny minority [but taxation in general remains a subject of fairness (see Piketty]. The tech giants, however, seem to have become dangerous monopolies because they are unregulated [page 24]

On the “Darwinian” dynamics of innovation, see also an older post, Silicon Valley will soon be 65 years old. Should she be retired?

Globalization ?

Companies that automate increase their employee workforce. [Page 28] Of course, this result only reflects average trends and does not mean that there are not negative effects on employment for certain technologies. For example, organizational innovations in logistics tend to reduce labor requirements. But it is very difficult to identify such cases with certainty; and, on average, the effect on employment is very positive. [Page 30]

Innovation for whom?

Due to the increase in inequality in the United States since the 1970s, the size of the market for products consumed by wealthy households is growing more quickly, and it is therefore on these markets that innovators are focusing their efforts. […] In an economy where the purchasing power of the most modest stagnates, which has been the case in the American economy for decades, the most modest never see the color of these innovations [Page 35]

The flow of innovations that generate purchasing power throughout society is not automatic: it depends on economic incentives. […] In the absence of a solvent market, there will be no innovation, so what can we do? [Page 37]

Some directions

Market size

It is estimated that a 10% increase in market size leads to a 3% drop in prices for consumers. [Page 42]

The sociology of innovators

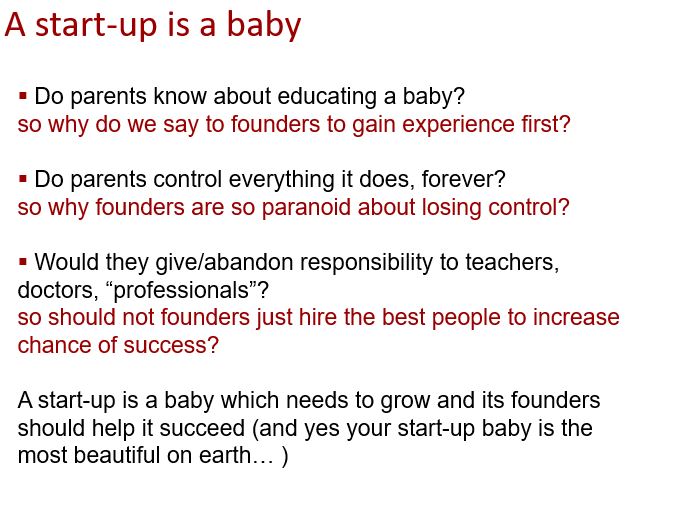

The innovative or entrepreneurial idea is often born by directly experiencing a need or a problem to be solved. If those who innovate are not representative of society as a whole, innovations are biased in favor of a minority, those of the privileged who innovate. [Page 43] And the author mentions the examples of Louis Braille and Joséphine Cochrane.

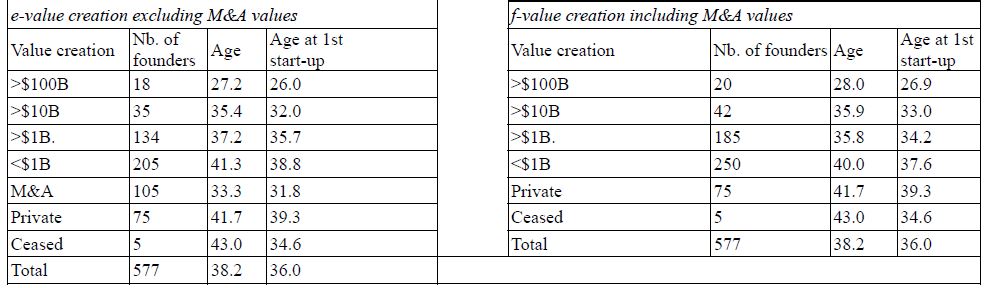

In the United States, individuals whose parents are in the top 1% of the income distribution are ten times more likely to become innovators. […] There is no self-made innovator: the social environment plays a major role. […] Same thing in France for individuals who become doctor-engineers or doctor-researchers. [Page 44]

Innovators are turning to consumers who are like them. [Page 46]

When it comes to innovation, the scope for public action is immense. [Page 48] Innovation policy has given an emphasis to financing innovation, with tax credits and direct subsidies […] Conversely, investment in education and public research has had a tendency to decline. […] States spend relatively little on innovation. The innovation policy consists of around ten billion euros. Of these 10 billion annually, the most important system is by far the research tax credit (CIR), amounting to 7 billion. [Page 51] Despite numerous analyzes attesting of its low effectiveness, the CIR remains the main instrument today. [Page 52]

Note by the way that this process is not accompanied by a public debate. […] It is a process in small committees bringing together senior civil servants, a few politicians and a few captains of industry, whose sociology is just as selective as that of the innovators, that is to say not very representative of the population in its entirety. [Page 52]

Education

X. Jaravel devotes a long chapter to the importance of education in all its dimensions for the least privileged as well as for the highest potential, in the sciences as well as behavioral skills, to combat all the biases of the sociology of innovators who are basically middle-aged white men [page 47]

For example, those who excel in the International Mathematics Olympiads will not always have the opportunity to do a doctorate, due to lack of opportunities in their country. That’s so many researchers and innovators lost. [Page 53] With the reference “Invisible geniuses: could the knowledge frontier advance faster?”

Education produces its effects in the long term, which does not attract the attention of those in a hurry, obsessed with other, more short-term priorities. [Page 56]

In his chapter 4, the author explains his skepticism about the taxation of the rich, the establishment of a universal income, the taxation of robots, protectionism or planning, while qualifying his remarks, as he knows that acting on a complex system can have effects that are difficult to measure. Once again he expresses the blind spots of such decisions, due to very technocratic processes on the one hand, not very effective on the other hand, especially if they are not evaluated a posteriori and finally because too much of a role is given to innovative projects rather than education and training. [Pages 68-70]

In search of the lost Marie Curies

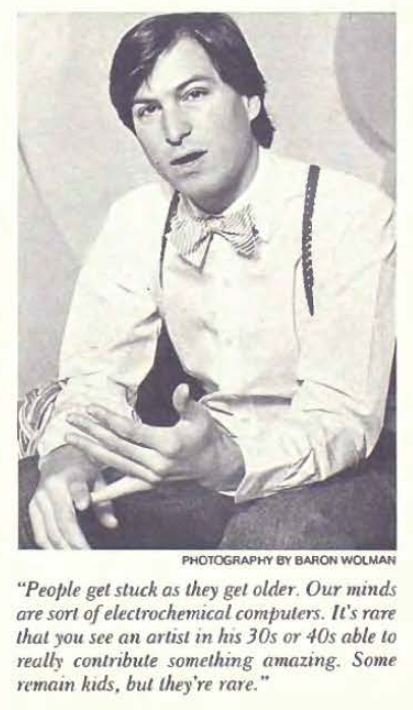

There are innovation clusters, not only from the point of view of the production of innovations, but also with regard to the origins of the new generation of innovators. [Page 74] Those who are most likely to become innovators in tech are those who have spent the most time in Silicon Valley, as if they were embedded in the environment and planned for these careers. [Page 76] Which makes me think of how many Robert Noyce, from a small town in the American Midwest, compared to Steve Jobs and Larry Page.

Achieving perfect parity between women and men to access innovation would increase the growth rate of labor productivity from 1% to 1.80%. [Page 78] We obtain equally important effects when we analyze a hypothetical situation in which individuals from disadvantaged backgrounds (rather than women) would no longer face any barriers in accessing professions in innovation and science. [Page 79]

It is also instructive to appreciate the effects of a very targeted policy which, by hypothesis, would achieve parity among the top 1% of individuals classified according to their aptitude for innovation. In the macroeconomic model, the most important innovations come from a small number of innovators (which is consistent with the data on the extreme concentration […] of start-up fundraising.) [Page 79]

The next pages are devoted to the impact of awareness raising in schools, an equally fascinating subject. Women are largely under-represented in scientific fields in France, which explains a third of the salary gap between women and men, which amounts to around 15% (for identical working hours). [Page 83]

X. Jaravel therefore insists on the importance of investment in education by emphasizing parity and territorial equality [Pages 85-6]. The author is concerned about the deterioration of education. Both in the basic “read, write and count” as well as on the best: In 2017, only 1% of students reached the level of the top 10% in 1987. [Page 91]

Three principles of action

– We know well that there is no single mechanism with a magical power, but that it is rather the conjunction of tools that makes it possible to change the situation.

– Under no circumstances should technical training be left aside.

– Several reforms could be specifically considered in their link with innovation and entrepreneurship. For example, introductory courses in entrepreneurship and innovation in high school, and strengthening teaching on the use of new technologies.

Democratizing innovation

At the end of his essay, X. Jaravel recalls two blind spots: a technocratic bias (leaving little room for citizens) and a limited use of evaluation. It is important to determine whether a scheme creates windfall effects or is truly effective. Thus an American study showed that certain subsidies constituted a pure and simple windfall effect when the subsidized technologies were already mature [while] conversely subsidies for start-ups at the very beginning of their life, in particular to realize prototypes had a strong ripple effect. [Page 110]

The author ends with three priorities:

– An educational policy that inspires vocations

– Do not give in to protectionist temptation

– Promote active participation of citizens

With the observation that innovation flows neither from the most brilliant entrepreneurs nor from the top of the State. Innovation is always collective, it infuses slowly, in the “rhizome” of innovation [Page 115]

I doubt that the reader in a hurry will understand much of these notes, and the author also indicates that this same reader could jump directly to the conclusion of his essay. You should read the full essay even if I doubt that the decision-makers often mentioned in Marie Curie habite dans le Morbihan – Démocratiser l’innovation will take the time to implement the recommendations, assuming they read them. But we must remain optimistic!