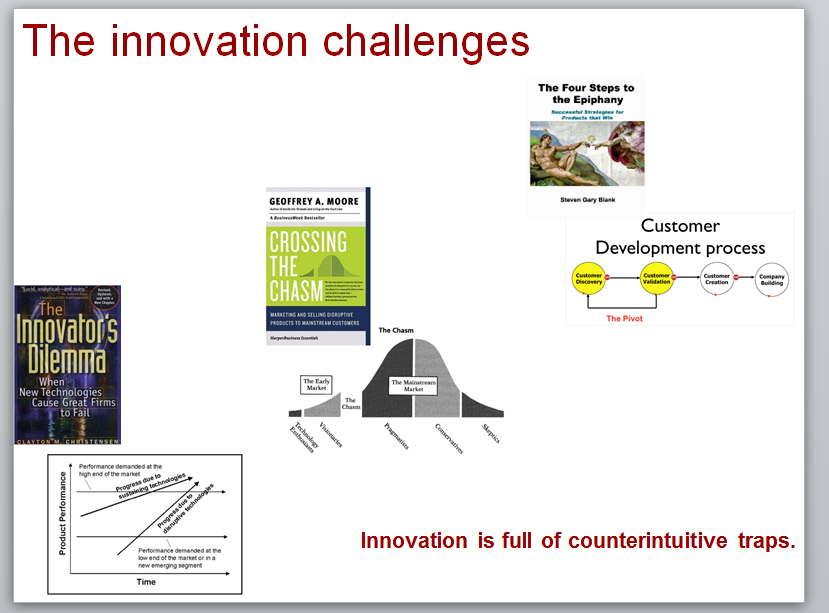

I do not know much about biotechnology (my background is IT). Though a start-up is a start-up, I always had the feeling that biotech was a different world. You often read that it easily takes ten years to develop a drug, so that biotech start-ups do not have any sales from products for even longer (with revenue coming only from R&D deals with big pharma). You also hear about going public through an IPO far before your product is on the market, something unusual in the IT world (except during the Internet bubble). Finally the financing needs from VCs seem to be much larger than in IT.

I have already written articles about this topic and you can find them under the tag biotech but I plan to write soon three new posts on the topic, related to recent readings and analysis:

– this post deals with my reading of Science Lessons – What the Business of Biotech Taught Me About Management by Gordon Binder, former CEO of Amgen & Philip Bashe.

– I will then give an update of cap. tables with 350+ companies. I will focus then on biotech firms.

– Finally, I should read soon another book, Genentech – the Beginnings of Biotech by Sally Smith Hughes. Hopefully it will be as good as Science Lessons. (And here is my synthesis, Part 3: Genentech.)

The Business of Biotech

Amgen is probably the biggest biotech firm today (with a market cap. around $100B in 2015). “The company debuted on Nasdaq stock exchange on June 17, 1983. Considering that Amgen didn’t have any products at the time, going public seemed premature to some observers. And it was; an IPO wasn’t in the original timetable at all. But our other sources of capital had shriveled up like foliage during Southern California’s dry season, leaving an initial public offering our only option.” [Page 6]

Amgen’s secret weapon

From the beginning, Amgen was a magnet for gifted, innovative men and women. How does an organization attract outstanding employees? […] Certainly we offered attractive salaries and benefits, and the stock options made available to every Amgen employee no doubt induced some folks to stay who otherwise might have sought opportunities elsewhere. As numerous studies have established, however, pay and perks aren’t what foster long-term employee loyalty. It’s something more profound, something that speaks to the very soul of a company. […] Because a company’s culture emerges from its values, we interviewed hundreds of staff members in all areas of Amgen to learn which values they believed constituted the core of that culture. Today it seems that every company under the sun (or under a cloud) has a values statement. Some are written by the CEO, and others are concocted by the public relations or human resource department. Sometimes they’re written by consultants who don’t even work there. More often than not, the statement doesn’t truly reflect the organizations values; it’s either a wish list of what the company aspires to be or a PR tool for impressing customers, suppliers, and investors. [Page 9]

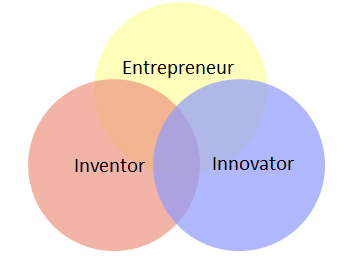

As Amgen grew exponentially, we constantly wrestled with the same quandary that confronts most flourishing companies at some point: how to remain nimble when you’re no longer a small start-up. You do it by decentralizing power, of course, but also by establishing an entrepreneurial culture that embraces change and encourages innovation. For that to happen, management must empower its people and then support them 100 percent, because staffers do not offer ideas freely if they secretly believe they will be hung out to dry should their promising project flop. In an industry such as biotechnology, failures abound. Had Amgen not lived its principle “Employees must have the freedom to make mistakes,” we would not have survived. [Page 14]

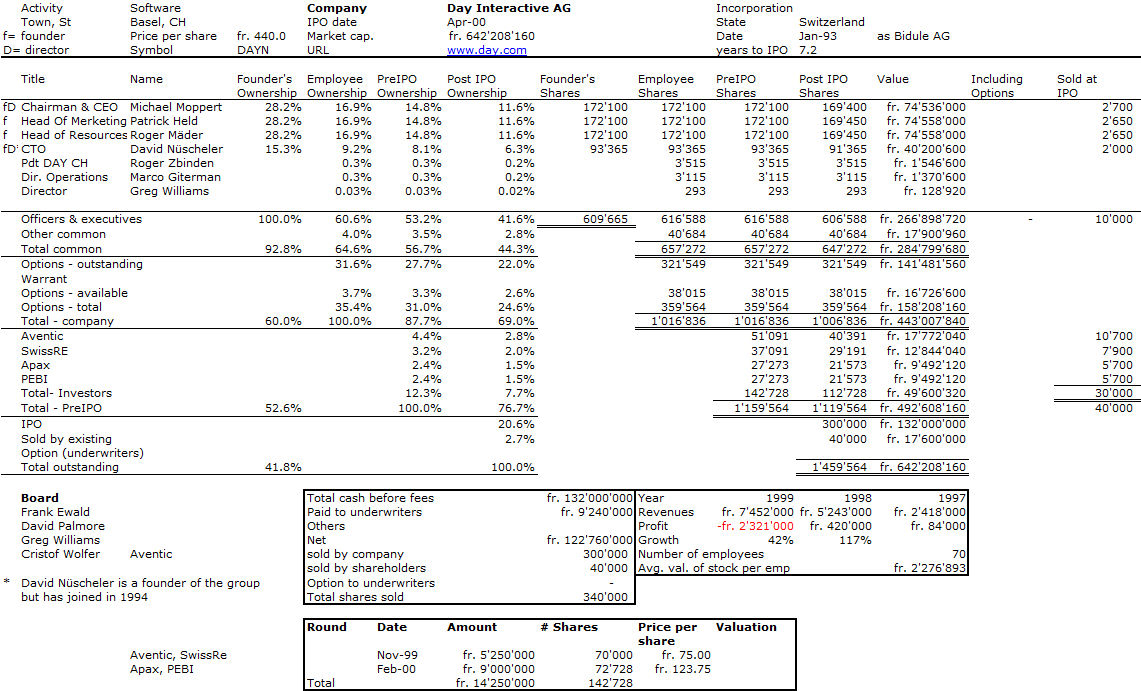

Amgen’s financings

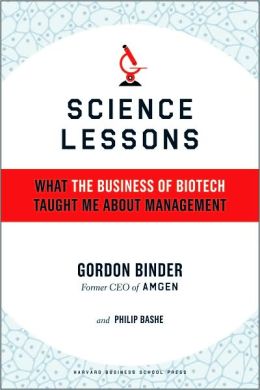

Amgen was incorporated on April 8, 1980. Then Bowes the cofounder and 1st investor “coaxed six venture-capitalist into putting up roughly $81,000 apiece in seed money.” [Page 18] George Rathmann became the CEO and only employee in the company. When the company needed a serious series A funding, Rathmann was convinced it needed much more than the typical $1M first round and looked for $15M. No VC would have agreed, so he convinced first corporations. Abbott invested $5M (which would be worth $700M in 1990). Tosco added $3.5M. And New Court (managed by Rothschild) would then invest $3M. The Series closed with $19.4M on January 23, 1981. Then the IPO brought $42M in 1983, but this was only another beginning as more public financings would follow: $35M in 1986 for the “secondary” and $120M for a third financing the next year.

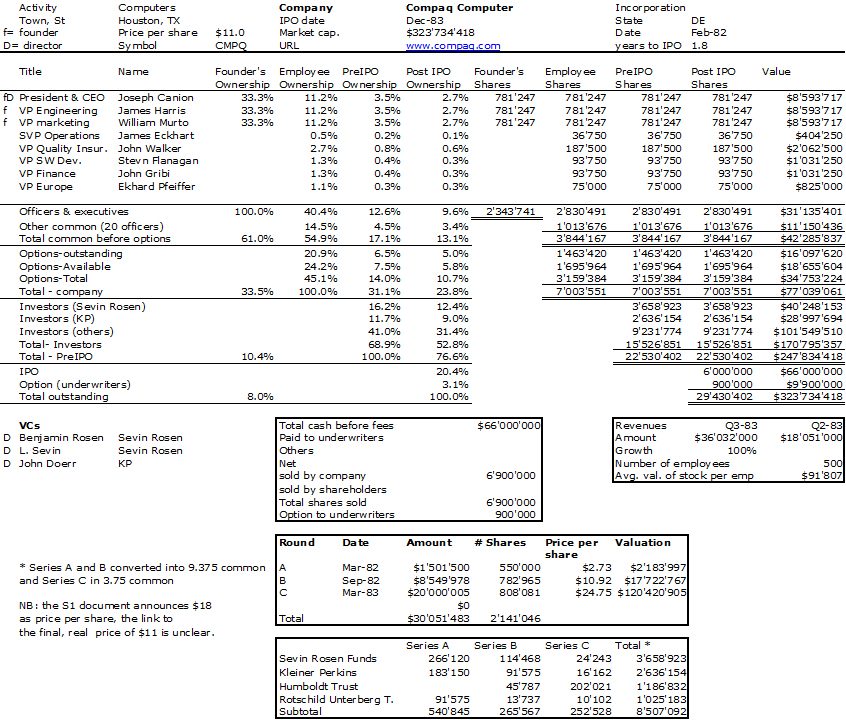

Here is the cap. table of Amgen at IPO:

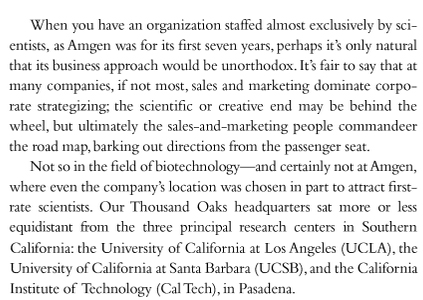

Though biotech start-ups have longer horizons that IT firms, the intensity of activities is very similar. Binder shows examples such as Amgen’s IPO (chapter 2), the discovery of EPO (chapter 4) and its FDA approval (chapter 5). There is however a major difference. Biotech is about science and research. “It’s fair to say that at many companies, if not most, sales and marketing dominate corporate strategizing; the scientific or creative end may be behind the wheel, but ultimately the sales-and-marketing people commandeer the road map, barking out directions from the passenger seat. Not so in the field of biotechnology and certainly not at Amgen where even the company’s location was chosen to attract first rate scientists. Our headquarters sat more or less equidistant to the three principal research centers in southern California: the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA), the University of California at Santa Barbara (UCSB), and the California Institute of Technology (CalTech), in Pasadena”. [Pages 57-58]

Amgen’s partners

“Success is the ability to survive your mistakes.” George Rathman

Chapter 6 (Partnerships Made in Heaven – and That Other Place) is a must read. Binder explains how critical good and bad partners may be and again this is linked to values and ethics. Binder claims that managers are much more careful when they hire someone than when they sign a partnership.

“Our search for a corporate partner started at home. Much to our shock, not a single U.S. pharmaceutical firm showed interest. […] Abbott Laboratories, one of Amgen’s original investors, had the opportunity to be involved in the Epogen project. CEO and Chairman Bob Schoellhorn turned it down. He’d been influenced by Abbott’s chief chemist, who apparently didn’t think much of drugs based on large proteins. As we would discover, that bias was not unique to Abbott; in fact it dominated traditional pharma. One company’s representative informed us that his bosses were passing on Epogen because the opportunity was too small; their market research department predicted sales would never eclipse $50 million per year (For the record, the drug generates $10 billion in annual revenue. Some market research!).” [Page 126]

Their first partner would be Kirin, the Japanese beer company with which trust, transparency and little paper work helped in building a great partnership. This was not the case with Johnson & Johnson. “To this day, contempt for Amgen’s former partner runs so deep that many employees proudly proclaim their homes to be 100 percent “J&J free.” Considering that Johnson & Johnson and its many businesses sell more than one thousand products, from Band-Aids to Tylenol, that’s no small feat.” [Page 133]

Amgen also has academic partners: “Memorial Sloan-Kettering possessed a mixture of about two hundred proteins. But it didn’t have the technology to separate them. Amgen did. […Amgen] discovered the human gene that produces G-CSF, located on chromosome 17. Once isolated, the gene was cloned using the same process as for human EPO. Memorial Sloan-Kettering had filed a weak patent, not knowing what it actually had. Therefore, said my general counsel, Amgen was legally free to process on its own, without paying a royalty to MSKCC. That didn’t seem ethical to me; without Sloan-Kettering, we wouldn’t have stumbled across filgrastim (Neupogen’s generic name). We negotiated a license with a modest royalty.” [Pages 143-44]

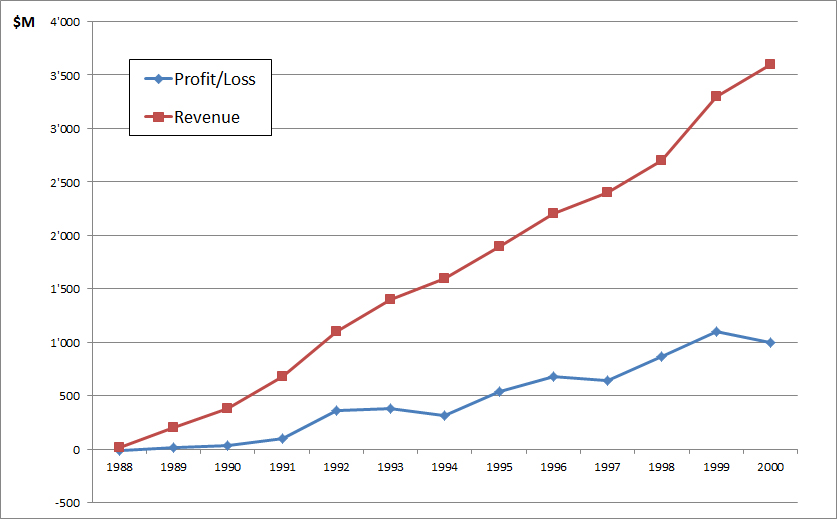

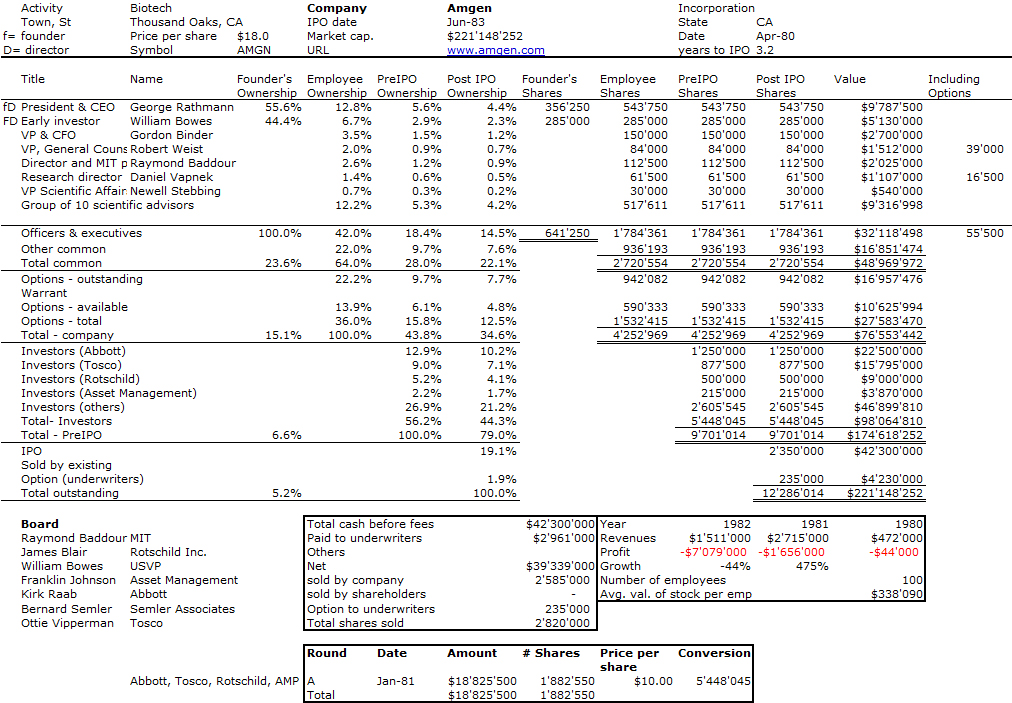

Finally for now, here is Amgen growth curve – revenues & profits. When a biotech start-up is successful, the numbers are impressive…